During my years as a food writer, I have championed the cause of regional cuisine as the only authentic culinary identity. I have scoffed at the mere mention of "Indian" food or curry powder, which I came across often enough in America. Yet it is becoming more and more apparent, even from faraway America, that an inevitable fusion of influences from disparate areas is changing the nature of regional foods and eating habits in India today. And in fact, there is nothing new about this trend. The same Bengali cuisine that I wanted the world to know and appreciate, instead of focusing on the ersatz curries and tikka masalas available in Indian restaurants everywhere, has also evolved and changed over the centuries. Even a casual look at the pages of Bengali narratives going back to medieval times shows significant differences from the way we cook and eat in Bengal today. With the passage of the centuries, Bengali cuisine has eagerly taken and absorbed exotic ingredients, and repeatedly been modified by external influences. The same is true of other regional cuisines in the subcontinent.

In this context, what is authenticity? In an unstable, mobile age, when do the borders of regional uniqueness relax? Is it possible for specialties rooted in ingredient, terrain, altitude, soil, and cultural beliefs to survive in a time of rapid perpetual motion?

- - - - - - - - - - - -

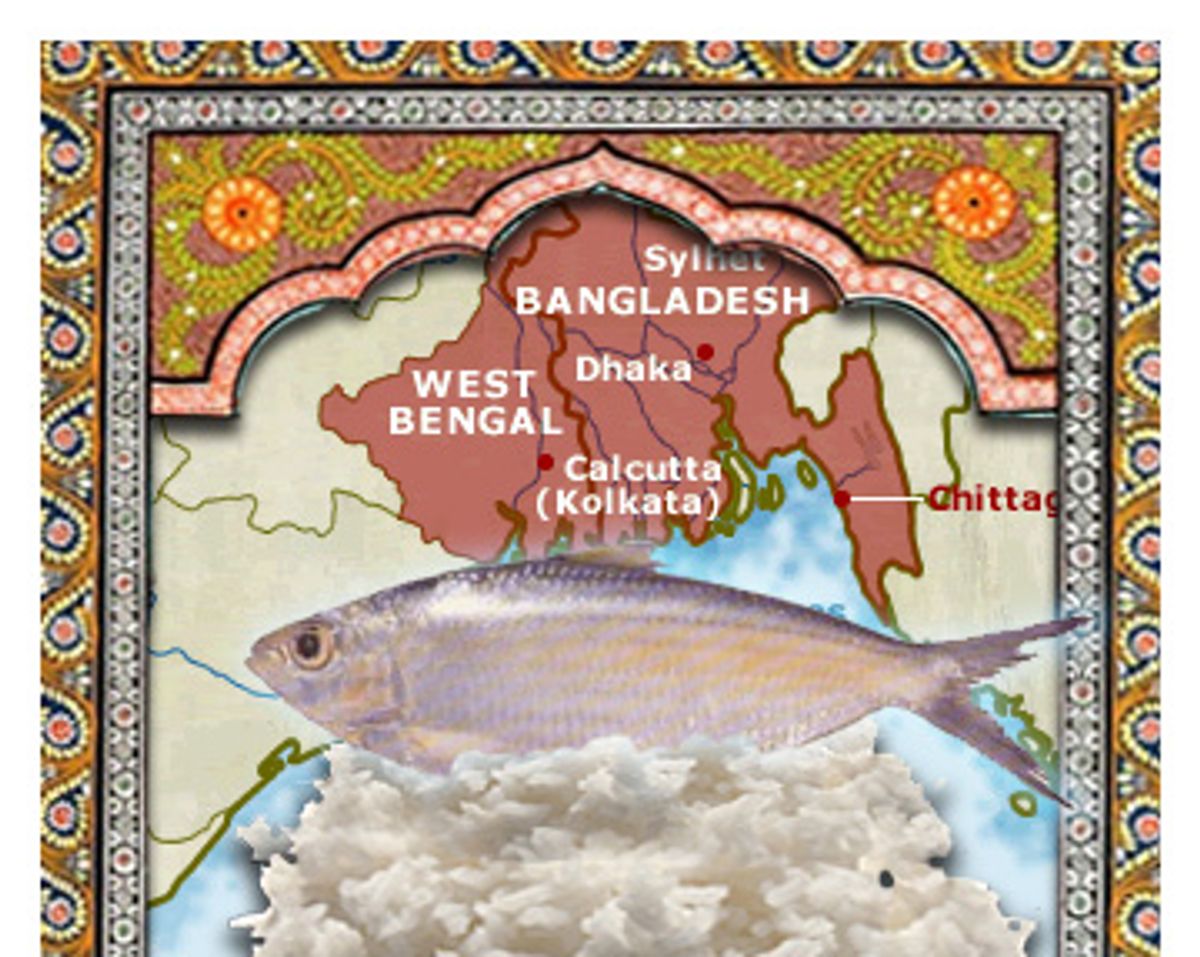

Bengalis love fish. Mention Bengali food to anyone in India, and the first image it evokes is that of fish and rice. Geography is responsible for the traditions -- from a high aerial perspective you can see Bengal (and historically, this includes both the Indian state of West Bengal and the country of Bangladesh) as an enormous delta in the eastern part of India, crisscrossed by rivers and rills too numerous to count. The smaller ones join up with the major rivers like the Ganges, the Padma, and the Brahmaputra, but eventually, they all find their way into the salty waters of the Bay of Bengal. On the map, you will see the emptying out of this collective water pitcher identified as the Mouths of the Ganges.

Fly lower down, and you see the land that makes the delta -- alluvial soil, renewed every year with the silt deposited by flooding rivers, precious as gold to the farmer. The presence of the rivers and the lakes and the rich coastal waters bordered by the mangrove forests of the Sunderbans, have automatically made freshwater fish a major part of the Bengali diet. Moreover, fish here, as in many parts of China, is not merely food. As a symbol of prosperity and fertility, it touches many aspects of ceremonial and ritual life.

In our extended family, my mother's kitchen was famed as a renewable source of gastronomic delight. And the one thing she loved above all was fish, no matter what its size, texture, or density of flesh and bone. As a picky and temperamental child, I didn't share her enthusiasm. Until I was old enough to go to college, when an expansion of my world helped develop my palate, there were only a few kinds of fish that I tolerated. The rest, however much they were recommended by mother and grandmother as "brain food," were anathema, particularly the tiny, excessively bony creatures that were either crisply fried or made into fiery, red-hot concoctions with julienned potatoes.

As I grew into my teens, what particularly aggrieved me was being dragged to the fish market by my mother, despite vigorous protests. She was determined that I should grow up with some sense of where my food came from. I hated the noise, the crowds, and the slippery, wet surface of the aisles bordered with gutters where the fishmongers, sitting on high slabs of concrete, threw out fish offal and dirty water with careless abandon even as they loudly touted their goods. Sometimes, my mother bought a fish head to cook with roasted moong dal -- a specialty that makes Bengali fish lovers salivate, while outsiders grow queasy. Choosing a majestic carp, she would command the fishmonger to cut off the head and then portion it. With fascination bordering on horror, I watched as the man picked up the huge fish in both hands and ran it with one swift, yet powerful movement against the blade of the bonti, a Bengali cutting instrument whose curving blade rises vertically out of a thick wooden wedge placed on the floor. As he triumphantly held up the head with its exposed dark red gills, it seemed more alive than the whole fish. Instinctively, I closed my eyes and held my breath lest some fishy spirit haunt me. Returning home from the market, I scrubbed my face, hands and arms with soap and water, and rubbed down my dress with wet hands, hoping to delete the odor of fish but uneasily aware of its lingering potency.

Arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as a graduate student, I discovered that nothing symbolized the contrariness of an outsider's life better than one's reaction to fish. In New England, a long maritime history has created an eating universe ruled by cod, halibut, tuna, salmon, bluefish, swordfish and other inhabitants of the great Atlantic, so much so, that the word "fish" is almost synonymous with seafood. But in those early days after arrival, I was ignorant enough to repeatedly fall into the trap unwittingly set by generous American hosts.

"Do you like fish?" they would ask as they took me out to dinner.

"Oh, yes," I would respond with Bengali enthusiasm, having tired of the large pieces of chicken covered with fatty skin, the hamburgers, and the recalcitrant cuts of meat labeled "London broil" that were served in the dormitory cafeterias of that time.

And so they took me to well-known "fish" restaurants. Each time, I ordered an item with a new name, and each time, I encountered the strong, briny flavor guaranteed to put off a person used to eating freshwater fish. In Bengal, where the rivers rule the land, the ocean is rarely explored as a source of fish. In fact, marine fish are traditionally considered inferior to fish harvested from lakes and rivers and are consequently much cheaper. All my favorite varieties were freshwater ones. Confronted by the disconcerting flavor of the fish served to me in America, I assumed at first that what I didn't like was the blandness of the preparation, the total lack of spices. If only the Puritan palate could embrace the tangy seasonings of my native land, what a difference it would make, I reflected as I picked at my portion. Since I didn't know how to cook, this was a natural mistake. Gradually, however, I figured out that this was a cultural, not a culinary divide: it was the seafood itself that tasted so foreign to me. And despite the many years spent here, I have not been able to cross it. The offerings of the sea, with a couple of exceptions, do not quicken desire in me. It is, however, a Bengali limitation, not an Indian one. The food of India's coastal states, like Goa, Kerala, and Maharashtra on the west, and Orissa on the east, includes many kinds of seafood transformed by intensely flavorful spices.

On a recent trip back to Bengal, I watched an old man lift an enormous wok onto the stove and, with hardly a pause for rest, pull forward a tray containing rows of cleaned parshey, one of Bengal's favorite fishes. Usually eight to ten inches long, these slender silvery beauties are cooked whole.

"What kind of sauce are you making for them?" I asked as he quickly dusted the fish with salt and turmeric powder.

He pulled out a plate containing dollops of freshly ground spices and pointed to mustard and posto (poppy seeds). In the wok, the mustard oil heated up and released its characteristic aroma. The old man threw in a pinch of whole nigella seeds and several split green chilies before putting in the fish, sautéing them, and adding the spices. As he transferred the cooked fish to a large enamel serving bowl, the heady smell of ground mustard and green chilies brought back the redolence of meals I had eaten during earlier visits from America. My father was still alive then, and my journeys were filled with anticipation, of the food he would buy from the market and the delightful dishes my mother would make for us to share. Parshey being a favorite of mine, my father always bought some for my first lunch -- fat, oily specimens, their bellies bulging with roe, cooked in a pungent mustard sauce similar to the one that I had just watched being made by the old man.

There are more varieties of freshwater fish in Bengal than weeks in a year -- or there were, according to narratives written as late as the mid-nineteenth century -- and these were to be found all over the land. Poor peasants who had no money to spend in the market could simply wander out to the paddy fields during the monsoon and pick up handfuls of small fish from the standing water. The so-called climbing perch, moving across land in search of water when lakes or ponds dried up in the summer, also became food for the finder. But as in so many countries, the growth of population, habitation, pollution, and over-fishing has left its mark on Bengal. In urban markets, fish is now an expensive commodity. Mythology, however, dies hard in the collective memory, and there are several species on which the Bengalis have lavished imagination, affection, symbolism, and desire in equal measure. The large rui -- especially the head, which is part of the ceremonial meal made for the son-in-law every summer -- and the giant prawns both fall into that category. But perhaps no other fish arouses as much emotion across the board as ilish -- the Bengali shad, which the British called hilsa.

The mystique of the hilsa can be understood only in the context of a larger Bengal which was split into two by the 1947 Partition of India -- West Bengal (in India), and East Pakistan, which later became the country of Bangladesh. For the inhabitants of pre-Partition Bengal, the only line of demarcation between east and west was the geographical line of the River Padma. The people on the eastern side were called Bangals and those on the western side were Ghotis -- both jocular terms used to convey rivalry, derision, superiority, and plain difference. Over time, the division was further reinforced by demographics, Muslims forming the majority in East Bengal and Hindus in the west. Cooking techniques and food preferences reflected both religious and sub-regional differences. However, a common bond of culture and language persisted through the centuries, creating a unique Bengali identity recognizable all over the subcontinent. Rice and fish remained the ideal Bengali meal on both sides of the border.

Nothing exemplifies this Bengali identity better than the region's love affair with the hilsa. The two major rivers in the east and the west, the Padma and the Ganges, respectively, have always been the prime sources for this fish which begins life in estuarine waters and then moves up river to spawn. During my school and college years in Calcutta, I often heard heated discussions between members of my family (rooted in West Bengal for countless generations) and their friends and colleagues who had migrated from East Bengal about which was the superior in flavor and taste -- the hilsa from the Ganges (that we swore by) or the one from the Padma. But this was a minor difference. There was absolute, indissoluble agreement over the fact that no fish can rival the hilsa's exquisite flavor or delectably tender flesh, not the large rui with its ceremonial and ritual status, nor the giant prawn with its rich, coral-filled head, nor the myriad other specimens that fill the waters of Bengal. In appearance, too, it had the edge, a full-grown specimen being nearly two feet in length, its small silver scales shimmering vividly, its eyes like pale blue gemstones even in death.

To me, the hilsa is both a memory of joyful family meals and a symbol of loss. It is a fish that is strongly linked to the Bengalis' seasonal appreciation of food. The first drenching downpours of the monsoon, when all creatures stir back to life after the searing, draining torpor of summer, are celebrated with that classic Bengali meal -- khichuri (rice and dal cooked together, flavored with ghee, ginger, and whole garam masala) and freshly caught hilsa. On other days during the monsoon, when the plump, kidney-shaped roe (much like shad roe in appearance) is available, it is gently dusted with salt and turmeric and sautéed in mustard oil to be eaten with plain rice. As for the fish itself, recipes for hilsa are too numerous to document, with families each adding their individual touches.

The hilsa was an item with which my mother sometimes constructed an entire meal. We started with a few pieces of fried fish and the roe. But the plain rice was enlivened by pouring over it the oil in which these had been fried -- the bare teaspoon of mustard oil in the pan usually increasing to half a cup with the rendered fat from the fish. The head came next, fried, broken up into pieces, and combined with the leaves and stems of a green called pui. The bulk of the fish was divided into two portions, one cooked with a ground mustard paste, its pungency merging into that of the mustard oil, the other (bonier portions of the back) made either into a jhal with hot red chili paste, or an ambal with tamarind pulp.

The likelihood of such meals has dwindled almost to the point of non-existence, not only for me in the absence of my parental home, but also for the region. The over-polluted Ganges is producing fewer and fewer fish, and very few of these are allowed to reach full-bodied maturity. In recent years, every time I have visited the fish markets of Calcutta, and asked about the hilsa, the vendors point to specimens that have been imported from Bangladesh -- the hilsa from the Padma that is bigger in size, and yet, to the West Bengali, deficient in taste and flavor. And even those may soon disappear as Bangladesh keeps exporting large quantities of frozen hilsa to Europe and America for eager Bengali expatriates. Bengali tradition, based on the ecological awareness that comes with an agricultural way of life, imposed a ban on eating hilsa during the crucial months of late spring and summer, thus allowing the fish to grow, mate, and spawn. But this graceful "darling of the waters" may well be doomed to an existence only in memory and legend.

Shares