My father was a news photographer. When he talked about his work he would say he didn't take photographs, he made them. There's a difference, he'd say.

I never asked him what he meant, but the distinction seemed important to him. I remember thinking when he said it that the word "made" sounded conspiratorial. I thought he was admitting that he somehow manipulated a scene he photographed, that he violated what seems a contract with the viewer. As Susan Sontag says in "On Photography," "The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what's in the picture."

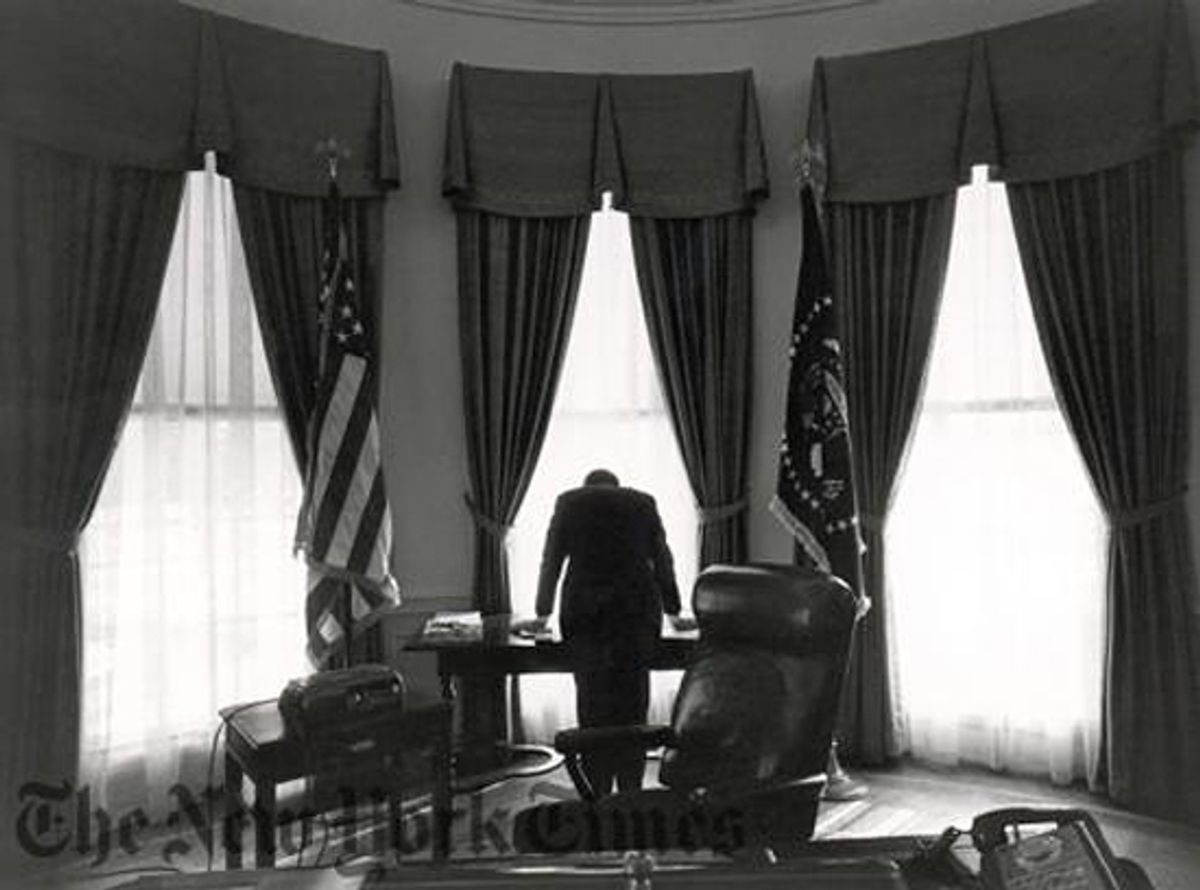

Sometimes people ask me how my father got a photograph, particularly "The Loneliest Job in the World," a photograph of President John F. Kennedy silhouetted by a window in the Oval Office. They want to know if my father composed the photograph in his mind first, and then asked the president to lean on the table. This is what my father said: He watched the president and saw that, because of the president's injured back, the president often went to the table at the window to read. My father waited, and when Kennedy moved toward the window and the table, he positioned himself with several cameras set at different exposures. He said he had seen an image in his mind and knew that underexposing the film would create more than a picture of the president. He took several frames from slightly different angles.

The photograph was part of a series that accompanied an article in the New York Times Magazine, where my father was chief photographer for the Washington bureau. When my father showed the president a mock-up of the magazine before it came out in the Sunday paper, the president looked at the photographs, pointed to the silhouette, and said, "That's the picture that should have been on the cover." Both the photographer and subject sensed its importance. They both knew the picture wasn't of a particular man leaning on a table. It's a picture of the president, standing in silhouette, seemingly deep in thought and carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders. The picture holds within it something more than what is seen.

When my father said he made photographs rather than took them, maybe that's what he meant. Anyone can squeeze the button on a shutter, as he liked to say. Back in 1961 when my father made that photograph, the image moved through a lens onto a piece of paper embedded with chemicals. That's it.

Maybe my father was prescient. Maybe JFK was, too. After the assassination, the photograph became famous. It was a symbol of the Kennedy presidency, the lost hope of a generation, Camelot. In some ways the photograph gave us solace, as if we saw in the president's posture an acceptance of his destiny.

Later, the picture seemed to hold within it the cumulative losses of the Kennedy family.

Now the image has been appropriated by anyone who wants to be seen struggling alone against uncertain odds, even if they aren't real. There was a three-second shot of Martin Sheen silhouetted against a window at the opening to the "West Wing" television show.

I remember my father once being angry when a photograph was disqualified from a competition because the judges thought it had been manipulated. It was a picture of a NASA rocket ready for launch. The photograph was taken at night, a full moon burned iridescent. The judges thought the moon looked too perfect, too round, too much the size of a quarter that could have been placed on the photograph during developing. My father shrugged off the criticism; to him the allegation said more about the judges than it did about his photography. That wasn't how he made pictures.

Yet my father wasn't above creating, or re-creating, a scene. Everyone in the family was called upon at some time to act as a model. My younger brother and I often went on assignment with him and were photographed walking through the National Zoo for a shot of the new bird exhibit and looking through a wall-size window at the Smithsonian. On a cold, icy morning, my father saw two schoolchildren on hands and knees pushing their books up the steep hill in front of our house. Within an hour my brother and I were doing the same. It made the next day's paper.

My oldest sister is the widow in "Widow's Walk," a winter snow scene at Arlington Cemetery, although she was neither a widow nor the wife of a soldier. She was a high-schooler, called on by our father to walk among the white gravestones at a prescribed angle after a deep winter snow. I have a memory of sitting in the car waiting for her to walk, then walk again, until my father was satisfied he had captured on film the image he sought. I was bored. She was cold.

The photograph was made in 1968. "Widow's Walk" had nothing to do with the Vietnam War, but it evoked the nation's growing discomfort with the war and the daily death count. Today, the photograph transcends any specific reference to a time, or even a place. It speaks to all loss.

My father wasn't on assignment when he made "Widow's Walk." He loved photographing Washington, particularly in the snow when the city's granite and marble buildings took on an ethereal quality. Washington, to my father, was as close to an earthly approximation of Mount Olympus as there was. Draped in fresh snow, it was as if the city sat atop pure white clouds. Every winter he tried to photograph what he felt in his heart.

When my father started work as a photographer in the early 1940s, photojournalism was in its infancy. In fact, photographers' work was seen more as craft and certainly not on the same level as the writers in the newsroom. But my father helped create a different aesthetic. Photojournalism became as important to the story as the story itself. Even today when video of an event shows up on the Internet in real time, it is the photograph we look to for meaning, that we search for some hint of the truth as if we are holding in our hands the actual moment in miniature.

Did he take photographs or make photographs? I'm still not sure what my father meant, if he was simply saying, for those who still didn't believe, that photography was more than craft? Or was he making a joke, something for which he was very well known? Was he confirming or contradicting Sontag?

Maybe I do understand. For my father, whether he changed the lighting, moved a piece of furniture, or stood in the shadows and waited for a scene to unfold in front of him, when he took a photograph he become a part of it and in that instant it changed from something he took to something he made.

By the way, the morning my father made the picture of JFK at the window, the president was reading the Times. He had gotten to the editorial page. My father said, "He looked over and he saw me. He hadn't been aware that I took that picture from the back, but he saw me when I moved to the side there. He glanced over at me, and he said:'‘I wonder where Mr. Krock gets all the crap he puts in this horseshit column of his.' Apparently he was much upset about Mr. Krock's column that day."

Shares