In my recent book "Back to Our Future," I spend a chapter looking at how our culture began changing from one that saw salvation in solidarity to one that worshiped the individual messiah. Through the deification of singular icons like Oprah Winfrey, Pat Robertson, Lee Iacocca, Rush Limbaugh and Ronald Reagan (among others), we started outsourcing our cognition to and projecting our aspirations on whichever Jon Galt we saw as our particular savior.

This fetishization of the individual has intensified since the 1980s. We see it in political activists' focus on presidential elections to the exclusion of almost all other political arenas. We see it in young people who have traded in idealistic "save the world" goals for dreams of celebrity. We see it in the revival of Ayn Rand's Objectivism as a powerful political ideology in Congress. We see it in both the left and the right mindlessly and unquestioningly parroting whichever cable-news deity they revere. Now, we see it even in America's ultimate team sport.

As a new University of Michigan study shows:

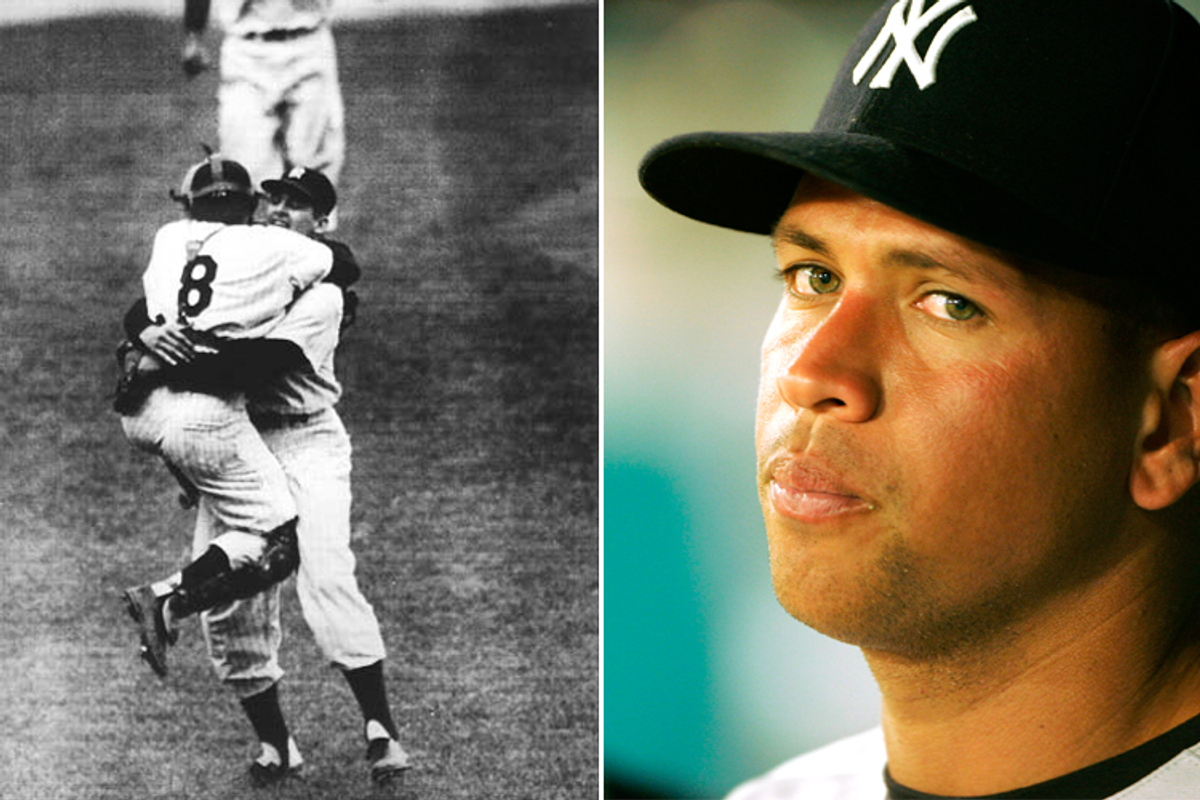

Spending top dollar for megastar players like Miguel Cabrera and Alex Rodriguez helps Major League Baseball teams attract fans and earn higher profits, but clubs that spend the bulk of their player payroll on a couple of superstars ultimately win fewer games, a University of Michigan study shows.

"Superstars who are paid more could bring more to the team in terms of profits," said Jason Winfree, an associate professor of sport management at the U-M School of Kinesiology. "The flip side of that is that a more equitable pay scale among all players results in more wins for the team, but not necessarily higher profits."

In aggregating ticket, merchandise and endorsement sales, overall profits are a direct dollars-and-cents reflection of fan interest. So while this study certainly documents important business trends inside the sports industry, it is more significant for what it says about the values of fandom in general. And what it says is clear: Fans are more financially supportive of individual superstars than they are of winning teams. Yes, for the baseball fan, it's the individual superstar, stupid -- and that means, according to the data, many Americans would rather watch a superstar hit lots of home runs on a losing team than watch a bunch of role players hit singles and win the World Series.

The Michigan study is a particularly significant representation of the pervasiveness of our hyper-individualist religion because baseball, more than probably any other major professional team sport, is the most resistant game to individual superstardom. Whereas a great individual scorer can take over every basketball game and a great individual running back can dominate every football contest, a great starting pitcher only appears in about one-fifth of a team's games, a great closer appears only for an inning or so, and a slugger typically only gets four or five at bats a game -- and the best of those sluggers will usually only notch a hit maybe two of those times. Yet, despite baseball's barriers to individual domination, fans in the age of hyper-individualism still reward baseball superstars more than they reward star-less teams that win games.

That said, considering the history, it's hardly a surprise that the worship of the individual is so powerfully reflected in sports in general -- even in those sports that are structured against the individual. That's because while political forces like Reaganism and Tea Party-ism have certainly helped intensify hyper-individualism, nothing has been more powerful in selling that ethos than professional athletics.

Think, for instance, about that silhouette of Michael Jordan singularly skying above his opponents -- and how that silhouette was (and still is!) emblazoned on all sorts of products. Think about Nike basically telling us since the 1980s that there is, an "I" in T-E-A-M as long as we are individually willing to "Just Do It" -- exactly as individual sports superstars do. And think about the recent steroids era of baseball, and how the MLB marketing machine euphorically marketed the breaking of individual home-run records -- all while pretending those grotesquely overbuilt sluggers just naturally willed themselves into Hulk clones overnight.

These representative examples highlight how sports have commodified and marketed individualism just as successfully as any political ideology -- and perhaps even more successfully, considering the fact that there are far more self-described sports fans in America than there are self-described political junkies. Indeed, as much as Washington pundits always ignorantly ascribe the moment's sociocultural zeitgeist to Beltway politicians, today's ascendant notion that the individual is more important than the common good is at least as much cultural as it is political -- as much a product sold in the sports arena as promoted by the electoral arena.

Shares