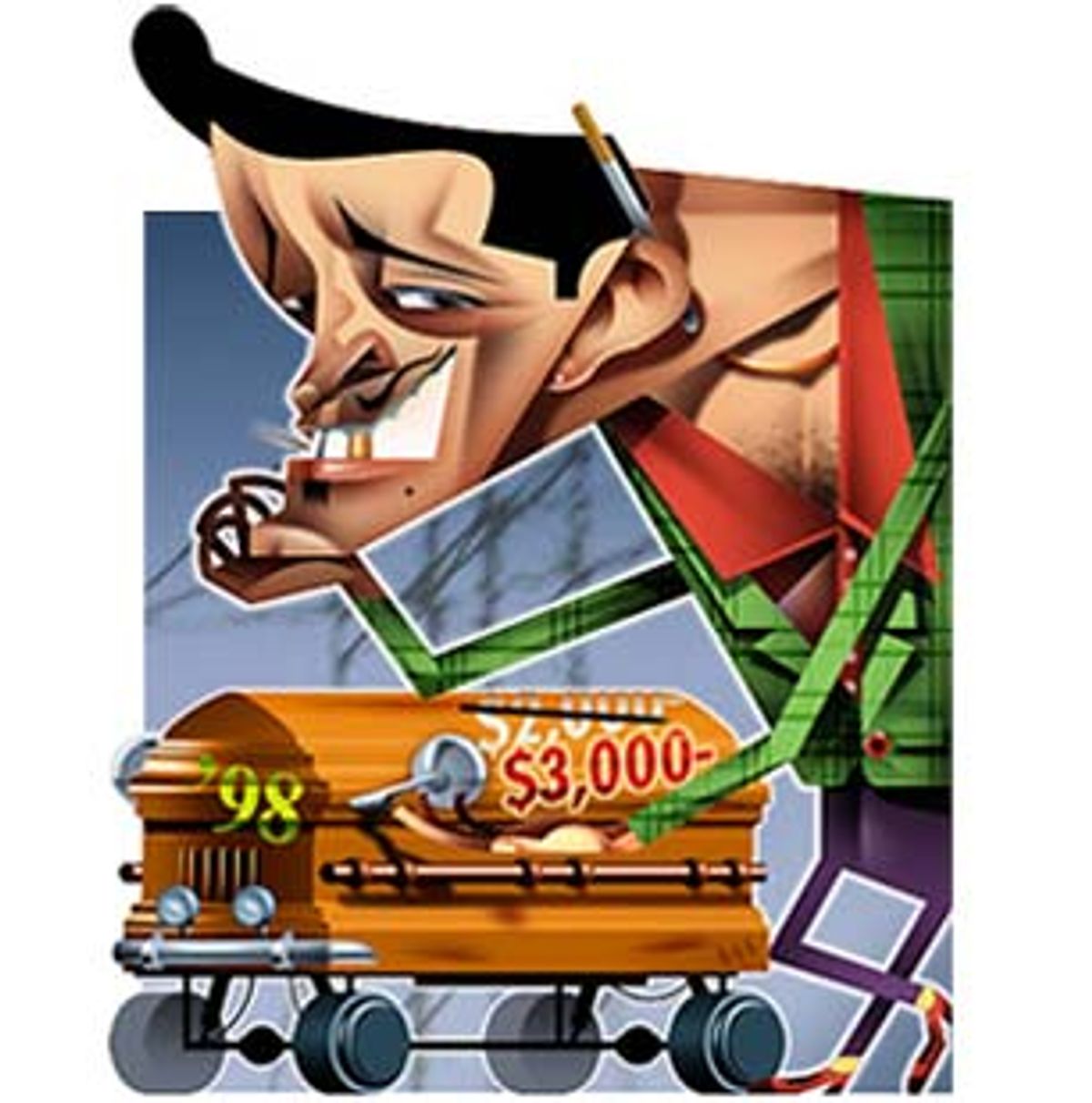

In 1993, funeral baron Robert Waltrip told the New York Times that people who don't buy his company's stock "just don't like money." For a time, Waltrip, the founder and CEO of the world's largest funeral company, Service Corporation International, was right.

SCI was the darling of Wall Street. Analysts praised it as a recession-resistant company with a great financial outlook and huge profit margins. After all, just as baby boomers shook the culture with every developmental milestone, soon they'll be dying in record numbers, and the titan of "death care," as SCI describes its business, seemed poised to profit from that long goodbye.

But over the past eight months, SCI's fortunes have faltered. In January, the company's stock price tumbled 44 percent in one day after it announced it wouldn't meet its quarterly revenue projections. A year ago, SCI's stock was trading at about $45 per share. On Tuesday, it closed at $11.25 and Wall Street analysts are decidedly bearish.

In recent months, SCI stumbled into the national media spotlight thanks to the presidential race. In March, Waltrip and SCI were named as defendants in a whistleblower lawsuit in Texas that involves allegations that presidential front-runner George W. Bush intervened on SCI's behalf to help stop an investigation by the state's regulatory agency. Waltrip and SCI are big financial contributors to Bush, and Waltrip is also a personal friend of former President Bush, endowing the Bush library with $100,000.

SCI has powerful friends in both political parties. Former Rep. Tony Coelho, chairman of Al Gore's presidential campaign, sits on SCI's board of directors. It's a lucrative job. According to the company's proxy statement, SCI pays Coelho $21,000 per year just to sit on the board and an additional $6,000 for each meeting he attends. Coelho also owns more than $450,000 worth of SCI stock.

Despite those influential friends, a number of troubling specters are creeping up on the company. Tort lawyers, consumer advocates and regulators are all taking aim at the Houston-based death care giant. Plaintiff's lawyers in Florida are suing SCI, claiming the company sold an exorbitantly expensive funeral to an elderly, mentally incompetent widow. In Washington state and Texas, lawyers are suing the firm, maintaining it has mishandled corpses. Company shareholders have filed a class-action lawsuit, alleging SCI officials withheld troubling earnings data that caused the stock price to dip.

Consumer advocates are constantly taking swipes at the company. Karen Leonard, the head of the Sebastopol, Calif.-based Redwood Funeral Society, who worked as the late Jessica Mitford's research assistant on her last book, "The American Way of Death Revisited," has become one of the country's leading critics of SCI. She claims SCI has "made price gouging state of the art.

"They've been able to take the emotions that make people spend more -- guilt and fear of death -- and have played those like an orchestra and have made tremendous amounts of money. They are taking advantage of consumers on all fronts, by secrecy, by their ability to control regulations and their ability to give money to politicians."

Lamar Hankins, the president of the Funeral & Memorial Societies of America, says the company routinely engages in "price gouging." Pierson Ralph, the president and director of the Memorial Society of the Southwest says "SCI's prices, generally, are obscene. They are clustered at the very top of the comparative prices. They are exorbitant everywhere you look."

SCI may be a target because it is the biggest funeral provider on earth,

and it owns many of the most prestigious funeral homes in the world. In Washington, it owns Gawler's, the firm that buried John F. Kennedy. In London, it owns Kenyon's, the funeral home that handled Winston Churchill's funeral. Over the years, it has buried other famous people including John Lennon, Howard Hughes and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

When I interviewed Waltrip for a magazine feature three years ago in his gigantic 12th floor office on the outskirts of downtown Houston, he expressed pride in the company he has built, and disdain for people who express too much interest in it. The reason for their morbid fascination with SCI, he said, is that "death has an aura about it." Sitting behind a massive desk, in a black suit and shiny black tassel loafers, Waltrip said he didn't care whether he got noticed by the press.

"Notoriety's not my bag," he said. "Getting a story written about me don't mean shit to me."

Some of SCI's detractors are individual clients who say their loved ones' funerals went awry. In Spokane, Wash., for instance, two families are suing the company, claiming that an SCI funeral home switched their loved ones' bodies, and cremated the wrong one. The lawsuit says that when the family of George Thiele went to see his body at the funeral home, they "immediately concluded that, although the gentleman on display was wearing Mr. Thiele's suit, and was in the casket that the family had selected for Mr. Thiele, the remains were not those of George R. Thiele." According to the suit, the funeral home cremated Thiele's body and put the body of Glenn V. Gossman in his suit and then showed it to Thiele's family.

According to the lawsuit, after the family insisted the wrong body was in the casket, a staff member told them the funeral home would "spend whatever money it takes to prove you are mistaken." In 1996, Washington's Department of Licensing reprimanded the SCI funeral home and fined it $4,000 for mixing up the two bodies. In the lawsuit, SCI has blamed the body switch on a company that transported the two bodies to the funeral home. The case will go to trial sometime next year.

In Texas, the company faces a lawsuit brought by the parents of television anchor Tres Hood, whose body was allegedly mishandled while it was being embalmed at an SCI funeral home in Dallas. Hood's mother Gayle Johnson, assumed his body was going to be embalmed in her home town of Wichita Falls. Instead, the procedure was done in Dallas at an SCI funeral home that had been investigated by state regulators for allegedly using illegal embalming practices.

According to the lawsuit, Hood's body began leaking embalming fluid shortly after the procedure was done and when his casket was put into a mausoleum, "problems with odors, gnats and fluid seepage began to occur."

In central Florida, lawyers filed suit against an SCI funeral home after an aggressive salesman apparently took advantage of an elderly widow who had been mentally impaired by a stroke. After several visits over a two-month period, the salesman obtained a series of checks and a pre-paid funeral contract for funeral goods and services costing more than $125,000.

According to the lawsuit, filed in Polk County, Fla., the funeral package included a casket costing $39,785 and a mausoleum costing $52,738. The suit says the widow was "not mentally capable to understand the contractual arrangements" and that she relied "solely upon the representations made by the Defendants." SCI denies the allegations. The suit goes to trial in November.

SCI general counsel James Shelger refused to comment on the

lawsuits in Washington and Texas. In the Florida case, Shelger said SCI is "confident that our position will be favorably viewed in the course of litigation."

Perhaps most worrisome for the company is a massive class action lawsuit filed on behalf of shareholders in February, shortly after the company's stock price plummeted. The suit claims that Waltrip and other SCI officials hid relevant facts from stockholders.

SCI blamed the revenue shortfall on "reduced mortality rates in the Company's major markets resulting in fewer funerals performed at the Company's locations." The announcement caused a massive sell-off of SCI's stock, causing its stock price to fall from $34 7/16 to $19 1/8 in one day.

Lawyers for the shareholders claim that Waltrip and other officials at SCI knew for several months that the company's revenues would be lower than expected, but did not tell shareholders all of the bad news -- a fact that the lawyers contend cost SCI's regular shareholders millions of dollars. The suit claims that Waltrip and six other SCI executives essentially bailed out, selling nearly 2.5 million shares of SCI stock in the months before the company announced the reduced revenues. According to press releases issued by the lawyers shortly after the suit was filed, Waltrip alone sold 1 million shares in the company, a move that brought him slightly more than $39 million.

Perhaps the most serious allegation in the lawsuit pertains to SCI's management of billions of dollars worth of prepaid funeral contracts. The suit alleges that SCI did not tell investors that it was losing money on many of its prepaid funerals. The suit alleges the company has a "multi-million dollar backlog of unprofitable preneed funeral contracts" and that SCI has kept the monies consumers have paid on those contracts in bank certificates of deposit and "other under-performing investments unable to grow sufficiently to cover the costs of performing the funeral services in the future."

In its annual report, SCI said "the lawsuits do not provide a basis for the recovery of damages because the Company has made all the required disclosures on a timely basis." The company also says it "has initiated aggressive action to defend these lawsuits." James Shelger, SCI's general counsel, refused to comment on the class action lawsuit, saying only that all the information on the case is "a matter of record."

Regulators are also nipping at the company's heels. New York City's commissioner of consumer affairs, Jules Polonetsky, has launched a frontal assault on SCI. Last February, Polonetsky's office released a scathing report about SCI's activities in New York, particularly in the Jewish funeral home business. According to the report, SCI owns 14 of the 28 Jewish funeral homes in New York. Prices at those SCI funeral homes are, on average, 50 percent higher than a Jewish funeral at an independently owned funeral home.

"SCI is gobbling up funeral homes all over the City and consumers are paying the price," said Polonetsky in a press release. "Instead of passing on the economies of scale to their customers, SCI is seeing its growing dominance as an opportunity to both reduce costs and raise prices."

Polonetsky said the New York attorney general has begun looking at SCI and added that he believes "there's a compelling case to take antitrust action and force them to divest some of their New York funeral homes." However, Sonya Sanchez, a spokesperson in the New York attorney general's office said the agency can "neither confirm or deny an investigation at this time."

On Aug. 25, Polonetsky's agency tried to implement four new regulations, including one requiring all of the city's funeral homes to disclose their ownership to the public. (SCI has consistently fought moves by various regulatory entities to force it to disclose which funeral homes it owns). The agency was promptly sued in state court by the Metropolitan Funeral Directors Association, which obtained a restraining order on the new regulations. Asked if SCI's consolidation of the funeral industry has been good for consumers, Polonetsky responded that SCI's efforts have "led to higher prices for consumers and less service."

In Texas, the company still must resolve a $445,000 fine that was recommended against the company last year by state regulators. So far, the company hasn't been required to pay a dime. Federal regulators are also examining the death care business. Last month, the Federal Trade Commission closed its comment period on its funeral regulations. The agency had been pressured by consumer advocates to toughen its policies on funeral homes in general and consolidators like SCI in particular. Last week, the General Accounting Office delivered to the U.S. Senate its report on the funeral business and the efforts by federal and state authorities to regulate it.

While Polonetsky and other state regulators can cause problems for SCI, the biggest threat to their dominance is the Federal Trade Commission, which enforces the nation's antitrust laws. On several occasions, the FTC has forced SCI to sell properties to ensure that the company doesn't become too dominant in a given market.

Despite the lawsuits and regulatory headaches, SCI remains the corporate giant that nobody has ever heard of. But then, anonymity is Waltrip's way. Although SCI buries more people than any other company on earth, few consumers ever know that they are dealing with SCI because the company, like most other large chains, doesn't change the names of the funeral homes it acquires.

While funeral directors pride themselves on their ability to soothe the emotions of the bereaved, the physical aspects of the job are really quite simple: Pick up a corpse, refrigerate it, embalm it (if needed), dress it, take it to the service, then cremate or bury it. And just as Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonald's, brought efficiencies of scale to the fast food business, Waltrip saw similar opportunities in the funeral business.

"Things about this business are the same as in McDonald's," Waltrip told me during our 1996 interview. Both businesses, he said, have a set of fixed costs. By buying in quantity and warehousing commodities -- like coffins and embalming fluid -- SCI reduces costs and increases profits. Once the company covers its fixed costs at a given location, up to 80 percent of additional revenues go straight to the bottom line.

"What we are able to do is very simple," says Waltrip. "And it didn't take a genius to figure it out."

As the son of an undertaker who grew up in a house connected to the family funeral home, Waltrip knew all of the facets of the business at an early age. In the late 1950s, he began to realize that he could streamline many of the tasks that had always been done by people like his father. He began building his empire with his family's funeral home in the Heights neighborhood in north-central Houston.

By 1957, Waltrip owned three funeral homes and was beginning to see the profit-making potential of owning lots more. And he began refining the business model that SCI uses today: cutting costs by centralizing operations. Rather than have an embalmer at each funeral home, SCI sends corpses to a central location where one embalmer can process multiple corpses. They also use a centralized delivery system to dispatch hearses, limousines and drivers to the company's funeral homes. Thus, one hearse and one driver can work two or more funerals in one day.

Waltrip's method proved profitable almost immediately. By 1974, SCI owned 132 funeral homes and its stock was trading on the New York Stock Exchange. Since then, the company has grown at a torrid pace. In 1990, SCI owned 512 funeral homes. Today it owns more than 3,800. It also owns 520 cemeteries and 198 crematoriums, and operates in 20 countries on five continents. The company's revenues topped $2.8 billion last year and it looks to remain perpetually profitable.

Indeed, Waltrip's business has advantages other capitalists would die for: the logistics and cost of entering the market keep competitors -- particularly foreign competitors -- at bay; customers rarely, if ever, shop for prices; everyone eventually needs the service; and as America ages, increasing numbers of people are dying.

Better still, many customers pay in advance. According to the company's latest annual report, SCI has more than $3.752 billion worth of prepaid funerals on the books.

Waltrip, 68, has taken home paychecks to die for. In 1996, Graef Crystal, the corporate compensation expert who wrote "In Search Of Excess," named Waltrip as the 12th most overpaid executive in the United States. In a study he did for Texas Monthly, Crystal determined that Waltrip was paid $20.3 million in 1997. That year, Crystal said "an average company of that size and performance, would be $2.259 million per year." Last October, Crystal hammered Waltrip again. The corporate pay analyst summarized Waltrip's pay package by saying he was "not worth it." Finally, in a June 20, 1999 analysis published in the New York Times, Crystal listed the SCI CEO as the third most overpaid CEO relative to stock performance.

In addition to his hefty paychecks, Waltrip is SCI's largest individual stockholder. According to the company's 1999 proxy statement, Waltrip owns 3.2 million shares of SCI. He likes horses and vintage warplanes and he spends lots of money on both. His collection of warplanes, housed at the Lone Star Flight Museum in Galveston, is estimated to be worth $17 million.

Waltrip has also been vigilant in protecting his public image. In 1996, his lawyers threatened to sue me after I wrote an article on Waltrip and SCI that appeared in Texas Monthly magazine. His lawyers also made veiled threats to sue the late Jessica Mitford while the famed muckraking journalist was writing her final book, "The American Way of Death Revisited."

In 1997, Waltrip did sue a critic, when he slapped former funeral home owner Darryl J. Roberts with a lawsuit. Waltrip claimed that Roberts' 1997 book, "Profits of Death: An Insider Exposes the Death Care Industries," defamed Waltrip and SCI. What was Roberts' sin? In his book, he quoted Waltrip as saying he wanted to turn SCI into "the True Value hardware of the funeral service industry." In their lawsuit, SCI said "the statement attributed to Waltrip is entirely false. Waltrip never made such a statement. The false attribution of the statement to Waltrip is defamatory and highly offensive to SCI and Waltrip."

Maybe it is. But then why didn't Waltrip sue Business Week magazine? After all, Roberts got the Waltrip quote directly from an Aug. 25, 1986, article in Business Week titled, "Bob Waltrip is Making Big Noises in a Quiet Industry." Nevertheless, SCI's lawyer claimed in court documents that the quote "suggests that Waltrip desires to create a company that projects itself to its industry and to the public as a mass market appeal firm devoid of personal, individualized identity and service."

A year ago, SCI and Waltrip suddenly dismissed their lawsuit against Roberts. But the suit cost the author $25,000 in legal expenses. Charles Babcock, Roberts' lawyer, said SCI didn't say why they were dropping the lawsuit. "Sometimes it's an effort to get somebody to shut up," Babcock said. "Typically libel litigation is an inhibiting factor on speech. It chills speech."

Wall Street analysts have soured on SCI stock. John Ransom, the director of health service research at Raymond James and Associates, has a neutral rating on SCI and the other big funeral home consolidators. "If you are an investor, you look for companies that are growing rapidly or are generating lots of free cash flow. With these companies I found neither. I'm not very bullish." Ransom says SCI is being hurt by competition from discount funeral providers and the growing popularity of cremation.

Josh Rosen, an analyst at Credit Suisse First Boston in Chicago, says that SCI is going through a major transition that will take time to resolve. But he believes the company will eventually work through its financial problems: "Fundamentally the death services industry is an attractive industry."

Shares