The main thing Joann Van Buren says she remembers about Timothy McVeigh is the $50 bill he wanted her to break. That, and the two men who accompanied him.

One day before he tore a hole in the nation's psyche with the bomb that destroyed Oklahoma City's Murrah Federal Building, McVeigh, Van Buren says, pulled up to the little Subway sandwich shop where she worked in Junction City, Kansas, driving the yellow Ryder truck that would contain the bomb.

Van Buren didn't pay any particular attention to them at first. Another clerk waited on the men, but when they tried to pay for their meal with a large bill, she took notice.

"As soon as the $50 bill came up, I had to go to the safe to get the change," says Van Buren today. "And when I gave them the change and they got their sandwiches, I remember them going back over to the corner, sitting down. And when they left, I remember three people getting into the truck. There were three people at the table."

The clerks she worked with later told FBI agents that two of the men matched the descriptions of McVeigh and his cohort, Terry Nichols. The third was a shorter, dark-haired and muscular man with an olive complexion: a perfect fit for the figure destined to be known as John Doe 2.

Luckily, the Subway shop actually had a video camera recording that day's events. When Van Buren contacted the FBI, agents interviewed everyone working in the shop on April 18. And when they were done, they confiscated the video recorded that day.

But if that tape showed a third co-conspirator with McVeigh and Nichols, no one outside the FBI can say. No one beyond the agency ever saw it. In the waning days of Nichols' trial, his defense attorneys discovered the details of Van Buren's story -- which had only been described in generic terms in the FBI's report, omitting her contention that two men accompanied McVeigh -- along with information contained in some 43,000 other "lead sheets" that the FBI until then had failed to turn over to them.

Michael Tigar, who led the Nichols defense, tried in 1999 to use the FBI's failures to produce all relevant documents to gain a new trial for his client. But U.S. District Judge Richard Matsch refused, saying the withheld material would not have altered the trial's outcome.

He likely was right. In fact, Nichols' jury had already refused to give him the death penalty largely because of some jurors' belief that more people were involved in the bombing than merely McVeigh, Nichols and Michael and Lori Fortier, the Arizona couple who were acquaintances with the two men and who were the prosecution's chief witnesses. That belief is also shared by thousands of conspiracy theorists who remain convinced the whole truth about the Oklahoma City bombing has not been told. Nichols' verdict stands as nearly the sole validation that the bombing may not have been the product of two lone bombers.

And when the FBI admitted it had failed to turn over another 3,100 documents to defense attorneys, fresh fuel was thrown onto those fires. McVeigh's execution was delayed a month as lawyers for both men started combing through the withheld information to see if it might give them an opportunity to overturn at least their sentences, if not their convictions. His execution is now scheduled for Monday.

But just as he hovered in the background of numerous eyewitness accounts like Joann Van Buren's, the figure of John Doe No. 2 almost certainly lurks within those withheld documents -- and he will continue to haunt the Oklahoma City case after McVeigh is executed. And, in an era that has seen more FBI foul-ups than any other time in history, the bureau's inability to explain away the repeated accounts of additional participants in the bombings has raised legitimate questions about the quality of its own investigation -- as well as fueled thoughts of larger conspiracies that will live beyond McVeigh.

Even the simplest investigations of seemingly straightforward crimes -- let alone a massively complex one like the Oklahoma City case, in which some 35,000 witnesses were interviewed -- can be complicated by the randomness and unrelated coincidences of real life. An unattached stranger who wanders onto a scene at some point can become a suspected accomplice for no reason other than bad timing.

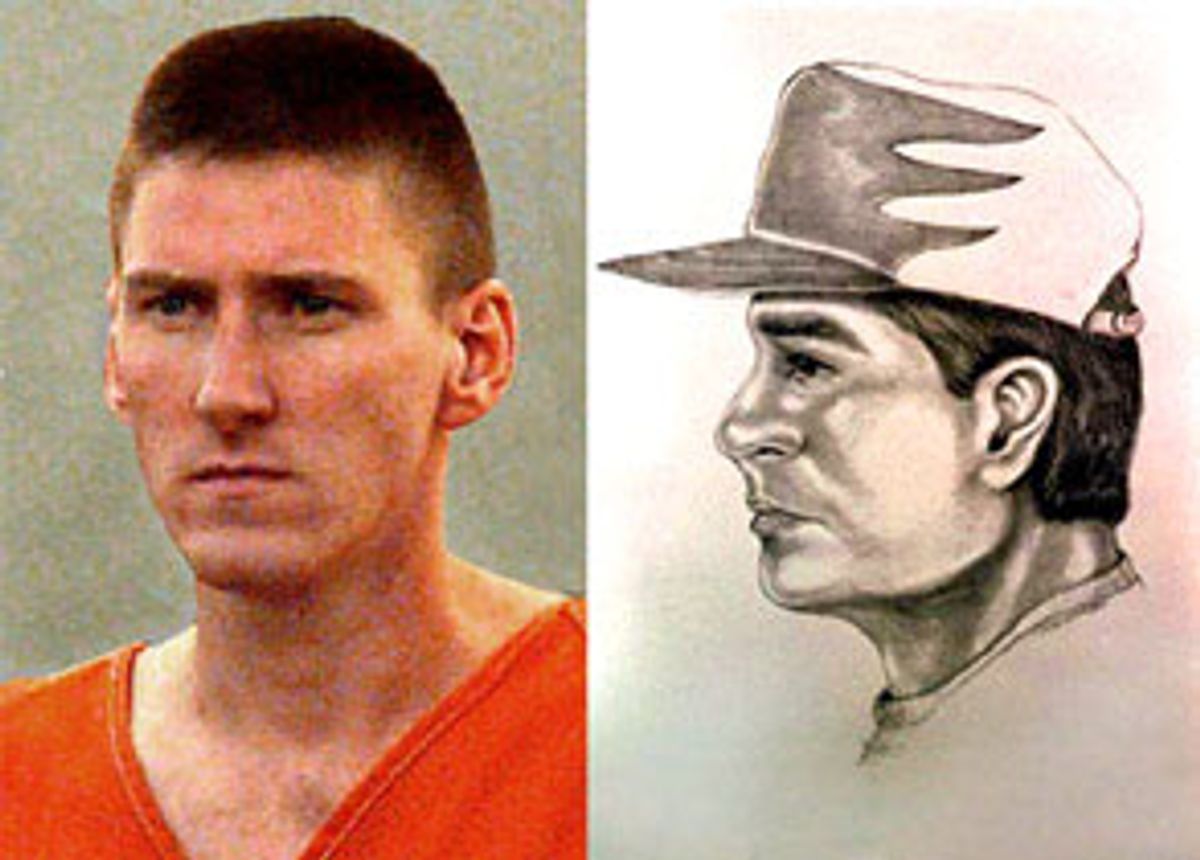

The FBI has maintained that coincidence is the best way to explain John Doe No. 2, whose character sketch was drawn mainly from the account of an eyewitness at the Junction City shop where the Ryder truck was rented. That witness, the FBI says, mixed up his recollections and mistakenly identified a man who came in the next day to rent a truck -- a 23-year-old soldier named Todd Bunting -- as an accomplice of McVeigh's. Bunting, who was cleared of any connection to the crime, vaguely resembled the composite drawing and wore clothes similar to those in the drawing, including a Carolina Panthers ball cap.

There is a kind of logic to the FBI's conclusion. The Oklahoma City case was anything but straightforward, and the agency was hit with a near-apocalyptic flood of tips about the possible perpetrators of the bombing. The vast majority of them turned into time-wasting dead ends and wild goose chases, and the investigators were forced to turn to Occam's Razor -- the maxim that the simplest explanation for a mystery is most often the correct one -- to shave down the possibilities.

McVeigh, a dead ringer for the John Doe No. 1 sketch, had been captured, and Terry Nichols (who looked nothing like John Doe No. 2) had turned himself in to authorities. The Fortiers were quickly tracked down and confessed to their relatively minor roles in the bombing as sympathizers who gave McVeigh a temporary base of operations and listened avidly as he planned the attack. And though there was no shortage of theories about the identity of Doe No. 2, no one who resembled him emerged as a possible co-conspirator.

Ultimately, investigators were forced to conclude that John Doe No. 2 was a phantom who never really existed. And that was the case they chose to take to the courts in their prosecutions of McVeigh and Nichols.

"There's nothing there," says FBI spokesman Steven Berry. "It's a case where every avenue we went down, there's nothing there. And we're certainly not going to get behind it and say there's something there or put it out that there is something when there's nothing there. It's chasing ghosts."

Indeed, McVeigh himself steadfastly denies there was any John Doe No. 2. He told the authors of "American Terrorist" that he and Nichols alone had built and detonated the bomb and vehemently denied that anyone else had been involved. He also denied the existence of Doe No. 2 in a May 2 letter to the Houston Chronicle.

But even McVeigh's own trial attorney, Stephen Jones, never believed him on this count. Jones believes McVeigh had substantial motive to lie about the involvement of others: For one, it covers the tracks of his cohorts, and it heightens his own role in the drama. Certainly "American Terrorist" captures McVeigh's desire for martyrdom -- he manipulated his appeals to expedite his execution -- and admitting anyone else into the scenario would certainly diminish his starring role.

Jones also told reporters that McVeigh failed a lie-detector test when asked about John Doe No. 2. And McVeigh, he says, frequently covered up any traces of potential co-conspirators. Once he insisted he had not accompanied Nichols to a farm co-op to buy ammonium nitrate, but after learning that a clerk at the store identified Nichols and said there was a second man with him, McVeigh flip-flopped, telling Jones he had been the man there after all. The clerk, on the other hand, insisted that it hadn't been McVeigh.

But when Jones' defense team attempted to track down Doe No. 2, it ran into the same dead ends as the FBI. Nonetheless, Jones himself came to believe McVeigh was associated with a gang of white supremacists operating out of an enclave in rural Missouri called Elohim City.

That theory is also a favorite of conspiracists who see the Oklahoma City investigation as a massive coverup. Many of them go well beyond Jones' relatively modest conjectures about the nature of the bombing to argue that the government itself was somehow involved in the bombing, as part of its plan to discredit the militia movement. The theory that McVeigh was set up looms large in the voluminous conspiracy theories that are the metier of the far-right Patriot movement. The Militia of Montana, for instance, continues to claim that there was a second blast -- a charge set by federal agents, they say -- recorded within seconds of the truck bomb (there was not; the seismic reports that form the basis of this claim actually recorded the impact of the mass of debris from the Murrah Building hitting the ground).

Others argue that a bomb made of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil could not have delivered enough force to cause the extraordinary damage of the Oklahoma City blast, and cite a study at a federal laboratory as proof. They are right. But then, the explosion set off by McVeigh actually was a high-octane mix of jet fuel and fertilizer, and the Murrah damage was entirely consistent with the force of that kind of bomb.

The theories that have gained the most currency among the conspiracy set are traceable to an Oklahoma journalist named J.D. Cash, who has built a minor career out of linking McVeigh's activities back to Elohim City and other violent supremacist factions. The core of Cash's theories revolve around McVeigh's connections to a handful of people at Elohim City who shared anti-government (and deeply racist) views, suggesting that McVeigh and his co-conspirators were actually dupes of a federal informant acting as an agent provocateur.

However, Cash's theories crumble in the face of a careful examination of the facts of the case. Cash makes much of the shadowy presence of a German neo-Nazi named Andreas Strassmeier and McVeigh's attempts to contact him at Elohim City in the days before the bombing. But Strassmeier had little contact with McVeigh and was nowhere near any of the activities that produced the bomb, and he steadfastly denies any connection. Cash's chief witness, an ex-debutante turned white-power pinup girl named Carol Howe who eventually worked as a Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms informant, has constantly changed her story in a way seeming to indicate that she was tailoring it to suit the needs of the conspiracists who promoted her tale.

These theories reached a kind of apex in the work of a British journalist named Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, whose 1997 book, "The Secret Life of Bill Clinton," postulated that the former president covered up the government's complicity in the bombing as part of a larger career of perfidy that included drug-running and murder. Though Evans-Pritchard's work gained some favor among mainstream conservatives -- Robert Novak, for instance, wrote a column extolling his theories -- nearly every aspect of "Secret Life" has been roundly debunked.

Cash's work surfaced again recently as a source for a report by the British newspaper The Guardian that linked McVeigh's activities to those of the Aryan Republican Army, a gang of Midwestern bank robbers whose whereabouts eerily paralleled those of McVeigh at key moments in the run-up to the bombing. However, like nearly everything proceeding from Cash, the piece was built on a fabric of coincidence and speculation.

Indeed, there has been no shortage of candidates for the identity of John Doe No. 2, but nearly all of them lead to the same kind of factual dead ends. And it is precisely those failures that tend to bolster the government's contention that the man in the sketch never existed as an actual conspirator in the bombing.

But the FBI's explanation of the John Doe No. 2 theories is nearly as full of holes as the conspiracists' scenarios -- or at least, it leaves dangling a long list of unanswered questions. When it is examined, a troubling portrait emerges of an agency eager to tailor its investigation for the purposes of prosecuting a criminal case, rather than doggedly seeking out the truth.

Joann Van Buren is far from the only person in Junction City and Oklahoma City in the days before the bombing who says she saw McVeigh in the company of someone besides just Nichols. And she is far from the only person whose tip seems to have gone ignored by the FBI for just that reason.

The most definitive claim of a John Doe No. 2 sighting came from Tim Kessinger, an employee of Elliott's Body Shop, where McVeigh rented the Ryder truck used in the bombing. Kessinger's description provided the basis for the sketch that the FBI circulated of the suspect, and he later testified that he had probably mixed up his recollections of McVeigh with Todd Bunting's rental the next day.

There were four employees present when McVeigh rented the truck, however, and all four continue to insist that a second man arrived and left with McVeigh. The shop's owner, Eldon Elliott, and a clerk testified in court to this effect during the Denver trials.

Likewise, nearly all of the 12 reasonably credible witnesses who saw McVeigh in Kansas, and whose accounts have been made public, say he was in the company of other men, sometimes two or more, and only a few of these identified Nichols as one of them. A Herington convenience-store clerk said McVeigh came in two days before the bombing with a second man who was not Nichols. The manager of the McDonald's across the street from Joann Van Buren's Subway shop said McVeigh and "his associates" frequented the restaurant.

It is similarly telling that the prosecution in McVeigh's trial never called a single witness who could place McVeigh in Oklahoma City the morning of the bombing -- largely because they too saw McVeigh with other people. A substantial number of these sightings include a man who fit the description of John Doe No. 2.

The most striking of these accounts come from a pair of highly credible witnesses who contacted the FBI early in the investigation and provided a description of the muscular, dark-haired man with McVeigh well before the FBI released the sketch of John Doe No. 2. One of them told an Oklahoma City grand jury that he saw Timothy McVeigh fleeing the scene of the bombing with such a man -- and reported it to the FBI the night of the bombing.

"I saw two individuals, Timothy McVeigh and John Doe No. 2, cross Fifth Street just minutes before the blast," said Rodney Johnson, 34, in his testimony. Moments later, the bomb blew out the windows of Johnson's truck.

Johnson said McVeigh and John Doe No. 2 "were in step, one behind the other. They were definitely together."

A similar account turned up in the withheld "lead sheets" turned over last month to defense attorneys. Morris John Kuper Jr. called the FBI two days after the bombing to urge the bureau to look into activities he witnessed in a parking lot a block away from the Murrah Federal Building an hour before the bombing. Kuper testified at Nichols' trial that he saw McVeigh with a man fitting John Doe No. 2's description getting into a light-colored car similar to the battered Mercury in which McVeigh was later caught. Kuper also said he called the FBI to suggest they check cameras at a nearby library and phone-company offices on the chance they might have caught something on video, "but they took my name and phone number and never contacted me again."

Almost as striking was the testimony, in McVeigh's trial, of a woman who lost her leg and her family in the bombing. Daina Bradley, who was standing in line at the Murrah Building's Social Security office that morning with her mother, sister and two children, saw the Ryder truck pull up to the front of the building. And she said she saw two men, not one, get out of the truck's cab. She got a clear view of only one of them, describing him as an "olive-complexion man with short hair, curly, clean-cut. He had on a blue Starter jacket, blue jeans, and tennis shoes and a white hat with purple flames."

However, Bradley's testimony was severely undermined when the 21-year-old admitted she had previously told investigators she had seen only the olive-skinned man get out of the truck. When prosecutors pointed out that she had self-admitted mental problems that affected her memory, some of them related to the trauma she suffered during the bombing -- all of her family members with her were killed, and Bradley herself had to be cut out from the rubble, by a doctor who amputated her leg with a knife -- she broke down on the stand.

The problem with all these accounts, as any criminologist can attest, is that eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable. Nonetheless, the breadth of the 20 or so people who saw the man fitting the description of John Doe No. 2 -- including those whose accounts preceded the wide distribution of the police sketch -- is striking .

John Doe No. 2 isn't the only riddle the FBI has failed to adequately explain. No one has apparently been able to explain, for example, the bombing's rarely acknowledged 169th victim.

When sifting through the debris of the Murrah Building, workers encountered numerous body parts, including nine severed legs. Only eight of those legs, however, were eventually matched up with bodies.

The owner of the ninth leg -- apparently a dark-skinned person, according to the medical examiner's testimony in the McVeigh trial -- has never been found, leading investigators to conclude that its owner was very near the blast when it occurred, and other body parts were obliterated by the explosion. There is the possibility that it belonged to a random passerby, but there are no missing person records relevant to the Oklahoma blast, and even extensive searches among homeless service agencies in the area failed to turn up any likely subjects.

There's also confusion around the question of how the bomb was constructed. McVeigh claims in "American Terrorist" that he and Nichols alone managed to load several tons of liquid jet fuel and ammonium nitrate into the Ryder truck and mix it into lethal explosive all in the span of three hours. Considering the difficulty of such work -- particularly that of mixing the chemicals -- McVeigh's account stretches the limits of credulity.

A more reasonable explanation for the construction of the bomb can be found in the testimony at Terry Nichols' trial. Charles Farley, a local sporting-goods rental shop worker, told the courtroom that he passed by Geary Lake at the time the bomb was being built, and saw not only the Ryder truck, a two-ton farm truck loaded with white bags of fertilizer and a car similar to McVeigh's getaway car, but at least five men working around the scene.

"Initially, when I got to the gate, there was one individual standing at the back of the farm truck, at the back left corner of the farm truck," Farley testified. "I seen three individuals standing down between the Ryder truck and the brown car, one of them standing in the -- in the road just a little bit, one of them leaning against the front of the Ryder truck and the other one just kind of standing between them."

Farley said he made to drive out of the area, pulling just beyond a gate nearby. "As soon as I was out, I seen an individual walking alongside of the farm truck. He was probably at the cab when I first seen him. And I was really going slow. I mean, I was just creeping. And I was going to roll the window down and ask him if he needed some help. And -- [he] give me kind of a dirty look and I decided, well, if you're going to be that way, me too, and I'm just going to leave; so I just drove away."

Farley said he couldn't identify any of the other men, but he got a clear view of the man who shot him a look. Nichols' defense attorneys handed him a photo of a gray-bearded man, and Farley said it was the man. The Rocky Mountain News later tracked down the identity of the man in the photo and found it was a 60-something member of a local Kansas citizens' militia group named Morris Wilson.

Strangely, prosecutors did not attempt to rebut much of Farley's testimony, which came on the last full day of defense testimony. It proved a crucial error in judgment. The jury convicted Nichols, but only of the lesser crime of taking part in the conspiracy and involuntary manslaughter, eschewing the murder and bombing charges that would have brought him the death penalty. Several of the jurors later said that Farley's testimony had convinced them that there was a wider conspiracy.

The jurors were not alone. In the sentencing phase of the trial, Judge Matsch himself indicated he was not convinced that everyone involved in the bombing had been brought to justice when he offered to lighten Nichols' life sentence in exchange for information about other participants. He said many questions about the case remained unanswered, adding: "If the defendant in this case, Mr. Nichols, comes forward with answers or information leading to answers to some of these questions, it would be something that the court can consider in imposing final sentence," Matsch said.

But defense attorney Michael Tigar demurred, explaining that Nichols couldn't discuss the bombing without jeopardizing his chances in the face of a near-certain second trial on state murder charges in Oklahoma. "We will consider your honor's words carefully," Tigar said, "but I hope it's understood that we don't labor here without those constraints."

There were other indications that Nichols was apparently prepared to start naming co-conspirators. And therein lies the most compelling evidence that there was a John Doe No. 2 -- as well, perhaps, as a John Doe No. 3 and even a John Doe No. 4 -- involved in the Oklahoma bombing.

But any chance of that went out the window when Oklahoma officials, eager to hand him the death penalty, decided to pursue their own case against Nichols. His murder trial -- which had been scheduled to begin this month -- is now on hold, as his new defense team sifts through the FBI's withheld documents.

The most famous instance of the FBI's disturbing propensity to take action built around a predetermined (and factually flawed) scenario is the Richard Jewell case, when agents decided that the former security guard had perpetrated the pipe bombing of the Atlanta Olympics in 1996.

Not only was Jewell's name dragged through the mire, but the trail of the real killer grew cold as agents focused their energy on a man later proven to be innocent. It was only when the likely bomber, right-wing terrorist Eric Rudolph, set off more bombs at gay bars and abortion clinics around the South that the FBI finally picked the trail back up. By then, of course, it was too late for his subsequent victims -- and Rudolph to this day remains at large.

Combine that with fiascoes at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, and Waco, Texas, where federal agents decided to bring the full force of their armaments into play against religious fanatics, and a pattern has emerged of an agency unwilling to shift from an original theory or plan of attack.

That stubbornness has frequently appeared in play in the government's Oklahoma City bombing investigation. A month before McVeigh's 1997 trial, prosecutors were prepared to argue that he had used a fertilizer-diesel oil mix for the bomb, even though there was clear evidence in lab analyses of the explosion's force that the bomb was not of that type. But the FBI had obtained receipts showing Nichols had purchased two tanks of diesel for his pickup truck, and had even gone so far as to enlist as witnesses entomologists who had done autopsies on dead insects found in puddles of diesel at Geary Lake, Kansas, where McVeigh and Nichols had put the bomb together. It was evidence FBI agents had found -- even if they knew it didn't prove anything.

But then, on the eve of the trial, Playboy magazine ran an article on the case that included information from documents leaked by McVeigh's defense team. In those documents, McVeigh had said that he used nitromethane, a high-combustion jet fuel, in the bomb and had obtained it at a racetrack south of Dallas.

"Of course, Lori Fortier had been telling them this all along, that McVeigh said he had nitromethane," says Kevin Flynn, a veteran reporter for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver who covered the trials. "But since they couldn't prove it, and they couldn't locate where he might have gotten it, they couldn't go to the jury with it, so they went with a false story -- a story they had reason to believe was false, that it was diesel fuel, only because they could show that Terry Nichols bought two tanks of diesel fuel that weekend, and that he had a siphon. So they were going to go with a false story, because they couldn't prove the one they thought was true."

According to Flynn's reporting, though, after the Playboy story prosecutors realized they needed more. "They went down to Dallas, they found the racetrack, they looked at the calendar, they got the race dates there in October and they tracked down all the nitromethane sales people. And one guy said, 'Yeah, a guy came in and paid cash for three barrels, who kind of looked like McVeigh.' He couldn't do a positive ID two and a half years later, but he was a credible enough witness that they changed their whole story on the eve of the trial."

There are other indications that the FBI chose to simplify the case at the expense of potential leads. According to testimony by the FBI's own fingerprint witness at the McVeigh trial, there were thousands of fingerprints recovered in the investigation. The witness testified on cross-examination that there were roughly about 1,100 fingerprints that they did not try to identify. Instead of cross-referencing them in a broad search, they simply checked them against a handful of potential John Doe No. 2 suspects. The agency has never explained why it chose such a limited check.

A more traditional problem with the FBI's modus operandi cropped up in the investigation, too -- namely, its high-handed treatment of local law enforcement officials, which often takes the form of ignoring important information they possess. This was especially striking to police in the rural Kansas precincts where McVeigh and Nichols constructed the truck bomb. A number of them offered leads that still appear promising, but their attempts fell on deaf ears.

"I can tell you that the frustration level around here was just enormous," says Suzanne James, a former deputy prosecutor in Topeka who had information on some of the militiamen with whom Morris Wilson associated. "When the FBI came in here, they just plain wouldn't listen to anything anybody local told them.

"If nothing else, I think the FBI owes the public an explanation, if these people were investigated, why they were eliminated as possibilities," says James. "Otherwise, you have one of these endless things like the Kennedy assassination."

Even analysts whose work is often devoted to debunking conspiracy theories are troubled by the lingering riddles in the Oklahoma City bombing.

"I think it's not a closed case," says Mark Potok, director of the Southern Poverty Law Center's intelligence-gathering arm. "I think that certainly there's the possibility that there are two or three or perhaps more people out there still. I absolutely don't think that's certain. That said, I think there's no question there are unanswered questions."

Now, the best prospect for settling the mysteries of Oklahoma City no longer lies with the investigators at the FBI, or whatever secrets may emerge among the thousands of recently disclosed documents. And it appears it may very well not happen before McVeigh is executed. However, not all of McVeigh's secrets will die with him. Nichols will remain very much alive, pending the outcome of his state trial. And in that setting, there is at least a reasonable chance -- particularly if the sentencing judge replicates the offer Judge Matsch made to Nichols -- that the identity of John Doe No. 2, or whoever it was that helped him bomb Oklahoma City, could finally come to light.

Shares