The United States inched closer to retaliating for last week's brutal terrorist attacks Thursday, moving U.S. warships and dozens of fighter planes to the Middle East and "possibly points east," according to Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. Neither President Bush nor Rumsfeld offered details on the movements, which are part of the campaign the Pentagon has dubbed "Operation Infinite Justice."

The dramatic designation falls rhetorically in line with President Bush's call for a "crusade" against terrorism and the states that support it, but how exactly will we implement it? How will the Bush administration fight what it has repeatedly called a "different kind of war?"

These questions don't have easy answers, but according to military experts, Bush will likely employ a complex combination of military approaches, in addition to diplomatic, law-enforcement and financial moves. A wholesale invasion and occupation of Afghanistan is extremely improbable, they say. Instead, experts expect localized, surgical strikes, both on the air and on the ground, which will then become part of a sustained campaign that will look more like police work than a standard military operation. The operation may carry the dramatic "Infinite Justice" title, they argue, but in fact, it will probably comprise a series of specific investigations and attacks, many of them unseen by the public and the press.

"You need to keep yourself from thinking in terms of a single response," says Gen. William Nash, who commanded 25,000 multinational soldiers in Bosnia, and is now director of the Center for Preventive Action at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington. "This is going to take a while, and by its very nature be a sophisticated and complex operation. And there will be a lot of different things going on, not all of which will bear fruit right off the bat."

Some of the assaults will have nothing to do with the military, says Michele Flournoy, senior advisor for international security at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington D.C.

"It's very important to put this in the context of the broader campaign and strategy, which includes non-military instruments," she says. "Law enforcement efforts here and abroad, denying terrorists access to financial resources and diplomatic pressure to keep governments from providing safe havens will all be used."

Regardless of these extra-military tactics, experts predict that the war on terrorism will likely begin with a conventional strike at Afghanistan. The redeployment of troops and carriers in the region, coupled with Bush's increasingly loud saber rattling, means it is likely that there will be some sort of strike on the bases and training camps that have been used by Osama bin Laden in recent months.

Most of these sites are probably empty of people and important supplies, acknowledges Harvey Sapolsky, director of MIT's security studies program. But "if there are places where terrorists train, I can't see that the U.S. will leave those alone," he says. "We will visit Afghanistan because we have a grievance against the Taliban."

The U.S. may target both bin Laden's camps and sites that are precious to the Taliban, Afghanistan's Muslim rulers. Missiles and planes, launched either from isolated bases in Pakistan or from aircraft carriers, could attack the Taliban's government buildings and military targets if the Taliban refuses to give up bin Laden.

Any future action in Afghanistan "will be in some ways similar to what we've been doing in Iraq," says Owen Cote, associate director of the MIT program. "We've basically been bombing Iraq steadily for the last couple of months, and there hasn't been a lot of attention focused on that. Here, I think you're going to be doing things on a relatively continuous basis."

After the initial attack, or perhaps in conjunction with it, special commando forces, which might be parachuted into the country, perhaps into the rebel-controlled north, could also be deployed. The air strikes could be used to force bin Laden's forces to abandon their hideouts, making it easier for ground troops to pick them off. "The idea is that when you put them on the run, they're easier to nab," says Flournoy.

Of course, if those hideouts cannot be immediately located, this strategy would not work. Air strikes also face a second potential problem. If bin Laden and his followers move to villages or populated areas, the military and civilian brass must decide whether or not to launch lethal air strikes that would kill civilians.

This kind of low-level attack may not seem to be a response commensurate to the dramatic strikes on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. But, Flournoy says, Bush must find a way soothe the call for wide-scale military action. "What they need to do is make sure that the public sees that the military operation is only the down payment," she says.

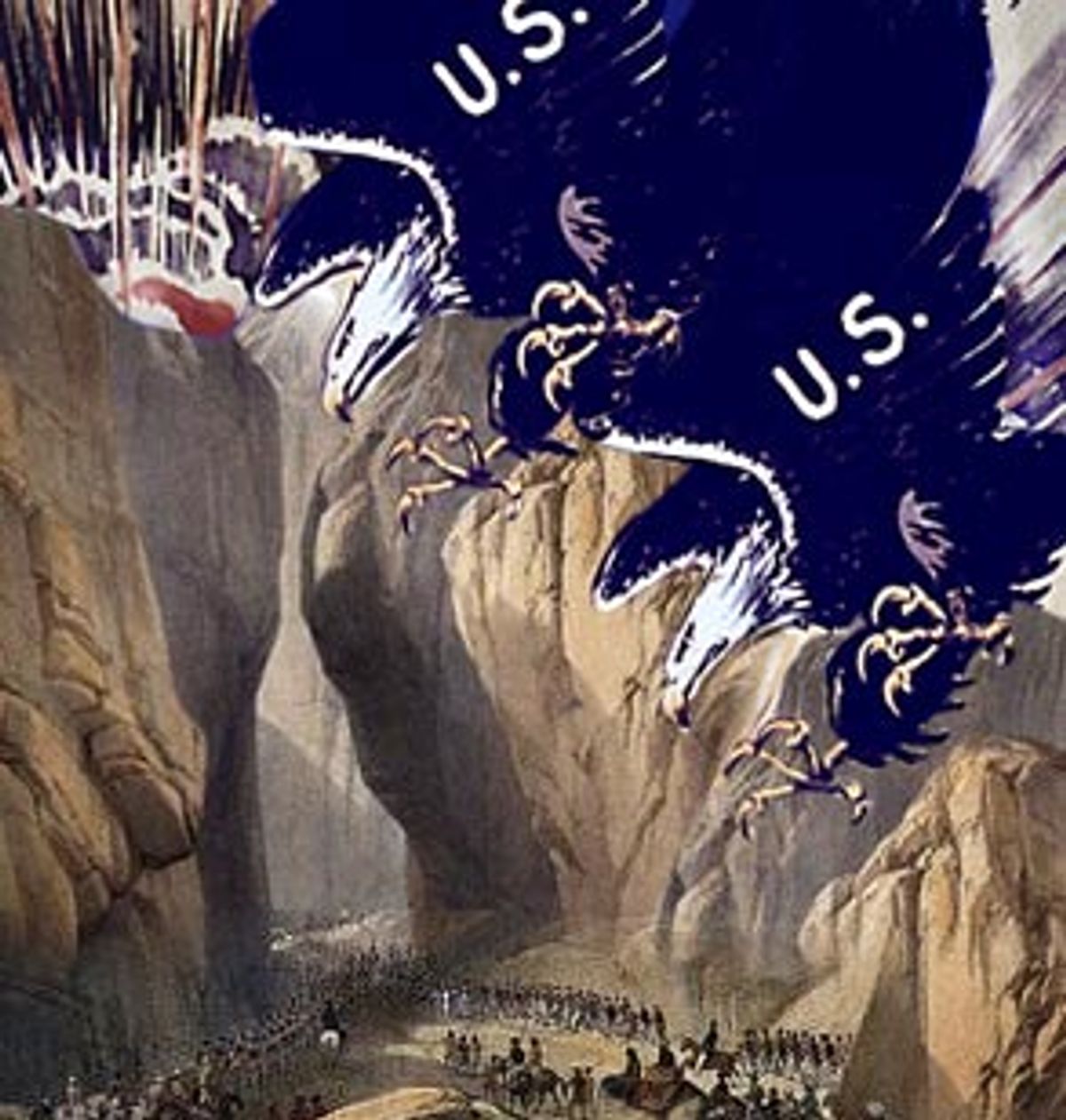

The terrain of Afghanistan will complicate any military action. The region where bin Laden is believed to be hiding is dominated by the Hindu Kush Mountains, which range from 10,000 to 15,000 feet. With little oxygen at that height, soldiers on the ground will have trouble moving around. Military machinery will also be severely affected.

"For helicopters [the mountains] are a real problem," says Cote. "You have to start off-loading fuel because you lose the ability to get lift. That means your range is greatly reduced. Also, you've got a ceiling of about 10,000 feet because helicopters are not pressurized, so you need additional oxygen. If you can't fly over the mountains, you're limited to the passes that give you access through these mountains, so you're kind of predictable. Certainly the Soviets discovered this in spades. And as we've seen in Somalia and elsewhere, there are lots of ways to shoot down helicopters."

Another threat: the brutal Afghan winter. There is already snow falling in the Khyber Pass between Pakistan and Afghanistan, and within a month, there will be a considerable amount of snow on the ground. The inclement weather will make it difficult for troops on the ground, as well as any air cover the troops may need.

If Bush decides to send anyone in, the difficult terrain and weather -- Afghanistan's best defense, according to most experts -- will make good intelligence vital. "American forces are going to want to go in and go out," Cote says. "A growing knowledge about what's going on in the country will provide [the U.S.] with the intelligence information to allow them to do that effectively."

But U.S. intelligence is playing a furious game of catch-up in Afghanistan. America is short of agents on the ground, a fact that became obvious earlier this week when FBI Director Robert Mueller publicly solicited resumés from Arabic and Farsi speakers. Building a reliable intelligence network will take time, and will be hindered by the fact that many terrorist groups are close-knit, and recruit new members only from families they know they can trust.

"I have just seen time and again the failures of our efforts. I was in Afghanistan in the late '80s; I talked to our chargé there," says Robert White, former U.S. ambassador to El Salvador and director of the Center for International Policy. "We didn't have any assets there."

For now, the U.S. is dependent on intelligence information from other countries, particularly Pakistan, a politically unstable Muslim nation which, in the words of Secretary of State Colin Powell, has "had its ups and downs" with the United States.

President Gen. Pervez Musharraf has agreed to "full cooperation" with Washington, which called on Pakistan to close its border with Afghanistan, make its airspace and land available to a U.S.-led force and exchange intelligence material.

But the U.S. must be wary of sparking a popular anti-American revolt in Pakistan. "I don't know if [Musharraf] has a good handle on the depths of support of the Taliban within his country," says Loren Thompson, chief operating officer of the Lexington Institute. "Most of the Pakistani commentators, who tend to be Western-educated elites, are minimizing the support for bin Laden and the Taliban within Pakistan."

"The danger is that we'll have a non-elected government that wants to help us and alienates its people in the process, not unlike the Shah of Iran. In Pakistan, it's not uncommon for the elites to get out of touch with the people. The ruling class is a patina of Western civilization upon a very volatile culture. Parts of Pakistan are like the Wild West."

One way to limit any anti-American backlash within Afghanistan or Pakistan would be to arm the anti-Taliban forces, the Northern Alliance, within Afghanistan. Talks between the Northern Alliance and the United States have taken on a "frantic" pitch, according to CNN. On Wednesday, Northern Alliance officials told CNN that in the past 24 hours, the U.S. asked for information on "possible targets including airports, weapons depots, military headquarters, training camps, troop positions and movements."

While using the Northern Alliance as a proxy to fight a war against the Taliban may help the United States adopt a lower military profile, the strategy poses a series of other problems.

Just before the attacks in the United States, Northern Alliance leader Ahmed Shah Massoud was assassinated, depriving the disparate band of rebels that make up the Alliance of their leader. Cote says the Alliance option was already problematic, and this makes it more so.

"It is far from clear that if we step in and try to support the Northern Alliance that it will have any effect," Cote says. "They fought a two-year war with the Taliban -- with heavy support from the Russians -- and the Taliban won. And now without Massoud, the movement is really a collection of small groups that now is without its leader."

"I'm sure it's being considered," says Thompson. "The main problem is the relative weakness of the Northern Alliance. They've only got a toehold left in Afghanistan, and now they've lost their most charismatic leader at the worst possible time."

Another danger in arming the Alliance is creating another military Frankenstein. The Taliban had tacit support from the United States, which at the very least looked the other way when the Pakistani government supplied the Taliban with weapons. Another example of the law of unintended consequences came during the 1980s, when the United States gave heavy military support to Iraq in its decade-long war against Iran, only to end up fighting its own war against Iraq in 1991.

But assisting the Northern Alliance is still one of America's best options, experts say. Afghan soldiers know the terrain, have a better chance of infiltrating the Taliban and, because they're fighting for their homeland, are "more invested in the battle," says Sapolsky.

Of course, the Soviet Union tried a similar strategy in the early 1980s. But the Soviet Union's failures should not deter American efforts, says Michael O'Hanlon, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. "Russia, frankly, is not as good as we are militarily, especially now," he says. They also didn't extend much support beyond small arms. O'Hanlon predicts that the U.S. will go further, offering air support and possibly tanks and high-powered artillery.

With added support, and since "we had a good track record in Bosnia with high levels of efficiency and success," he says, "I'm more optimistic about our prospects. Our chances are better than the Russians' were."

Regardless of political risks, Sapolsky says joining forces with the Northern Alliance, or arming them, may be necessary.

"In this kind of conflict, there are all sorts of dangers like that," says Sapolsky. "I'm taken aback by the desire for subtlety. We have a big grievance and taking care of it means that not everything will fall back into place, but I don't think it's avoidable. Yes, there will be some mistakes. You make mistakes all the time. We've had connections for years to people that seemed like mistakes. Ho Chi Minh, for example, had connections to us. [As a leader of the Vietminh, Ho fought the Japanese occupation force with American support.] But that's how it is. When we fight one enemy, their enemies become our friends."

The ultimate danger of the war may arise not from a war-by-proxy approach, but from extended attacks in other Muslim countries.

"This is a classic case where good planning has to focus not just on the United States, but on [the campaign's] aftereffects," Sapolsky says.

While speculation about possible military retaliation has focused on Afghanistan, Bush has made clear from Day One that terrorists in any country would be targeted. Bush reiterated that Wednesday during a press conference with Indonesian President Megawati Sukarnoputri in the Oval Office.

"This is a war not against a specific individual, nor will it be a war against solely one organization," Bush said. "It is a war against terrorist activities."

Thompson said he suspects that, eventually, evidence will point toward Iraqi involvement in last week's attacks, which will lead to a full-scale military strike against that country.

"I'll guarantee one thing," he said. "We're going to find out that Iraq had a role in this. And if we do in fact determine that the Iraqis had an active role in this, I think you'll see a ferocious military campaign in three parts. You'll see the continuation of our standard bombing campaign, only bigger, a focused ground intervention to destroy their weapons of mass destruction, and a special operations force sent in to kill Saddam Hussein."

Thompson speculated another war in Iraq may come before any action in Afghanistan. "I think that's true for a number of reasons: The terrain is more inviting, we have the country ringed with bases and friends, and we already know where the key assets are," he said. "And we have reason to believe that the Kurds in the north and Shiites in the south don't have much use for Saddam Hussein."

Sapolsky agrees that Iraq is likely to be a target of U.S. force. "I'm reading an article in Jane's [the respected military publication] that blames Iraq for a lot of this. Iraq is on the list [of nations we will target]. Whether they're first, second, or third is hard to know. But politically, it won't be possible to leave Iraq standing."

While Cote says there are "lots of other groups" of known terrorists, he doesn't expect military action against any group unless they can be linked directly to last week's attacks, or are linked to any future anti-American plots.

"There's Hezbollah that Iran supports, there are two Palestinian groups in Syria, Hamas, Islamic Jihad in Egypt, groups in Algeria and Sudan, and some other smaller groups in places like Yemen, for example," he said. "It's going to be a real threshold for the administration to cross if they do target groups that are not directly implicated in this attack. There will be pressure to come up with some link to this attack or other attacks on Americans before force is used. But to simply say 'You're a terrorist, I'm going to come get you and you who are hosting this person,' I think that's going to be hard to do."

Instead, says Sapolsky, the nation should brace for a long, protracted, and often secretive war against terrorism. The first battle in that war, he says, must be won behind the scenes, through diplomacy. "Most of it has to be police work, where you find terrorists and roll up the net on them," he says. "The difficulty of that is that it requires a lot of cooperation."

Additional reporting by Laura Rozen

Shares