Malek Francis, chairman of the American Lebanese Congress, remembers his alarm when he heard that a 21-year-old Middle Eastern man had been arrested in Pittsburgh Oct. 28 trying to board an airplane with a knife. "Right away I wondered if he was one of them," Francis recalls, referring to the al-Qaida operatives who hijacked four planes Sept. 11 and turned them into missiles aimed at New York and the Pentagon.

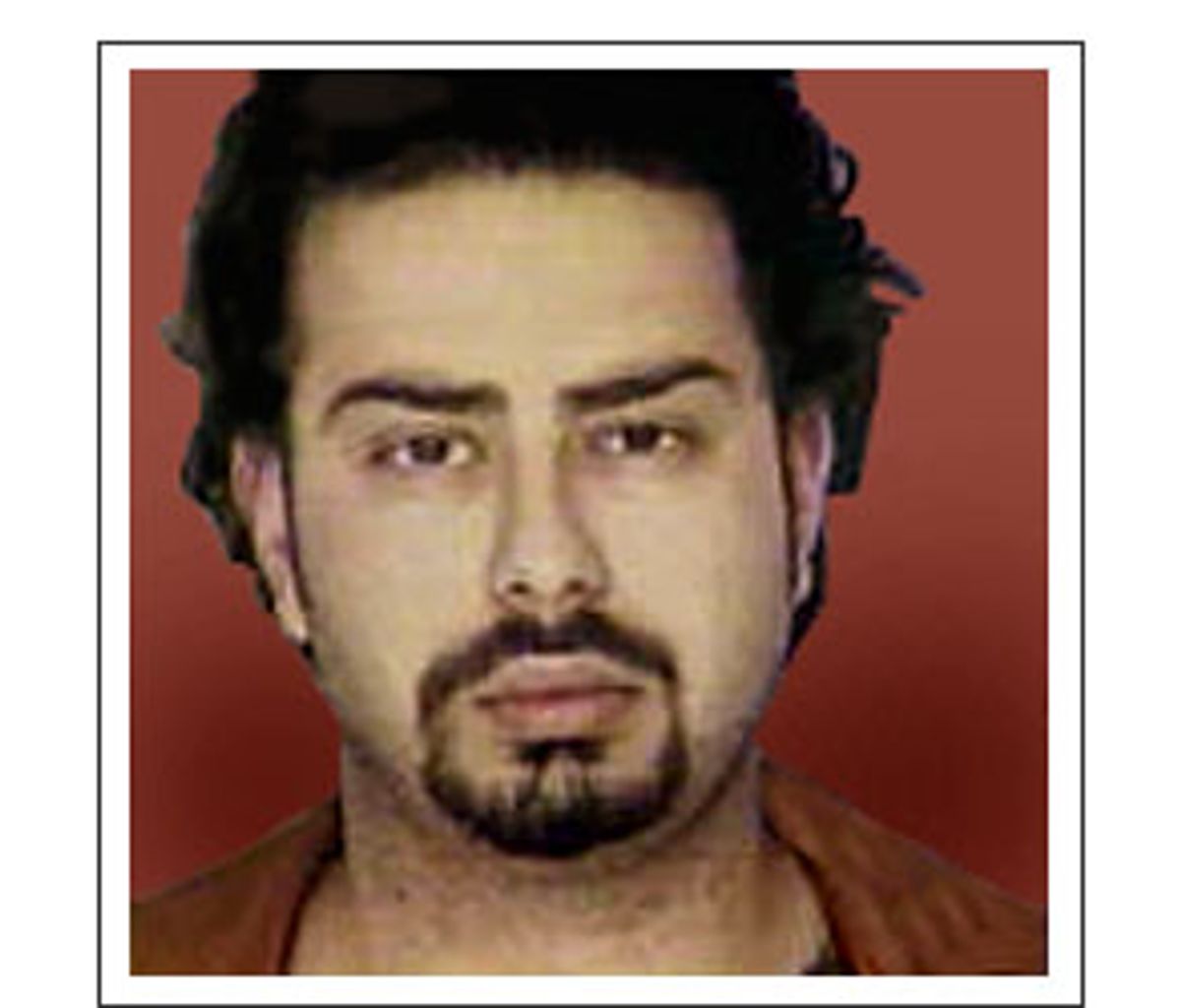

Certainly Pittsburgh media thought so, at first. TV news bulletins reported that an "Arab" was "prevented" from "smuggling a knife" aboard an airplane, which was variously "hidden" or "stashed" in his laptop case. The mug shot that accompanied newspaper stories the the following days confirmed the public's worst fears: a dark-skinned, goateed young man, with the type of brooding expression that seemed to hint at coming violence.

Because the young man, Salam Ibrahim El Zaatari, was from Lebanon, Francis was soon asked to get involved in the case. The American Lebanese Congress works to improve relations between Arabs, Christians and Jews; Francis has been honored for his activism by an invitation to the White House, courtesy of former first lady Hillary Clinton. The transportation engineer says he was initially skeptical about El Zaatari's innocence. "If he was guilty, then I didn't want to get involved with him," Francis recalls. "I wouldn't have anything to do with someone like that."

Six weeks after El Zaatari's arrest, his advocates -- including an outraged Malek Francis -- say the former Art Institute of Pittsburgh student was guilty of nothing more than failing to notify immigration officials that he'd left school, and forgetting he had a disposable utility knife he used in his artwork tucked into his laptop case when he boarded a Northwest Airlines plane bound for Beirut via Detroit and Amsterdam. Since then, he's been held without bail in Allegheny County Jail, locked 23 hours a day in a cramped protective custody cell, frightened of the other prisoners who have threatened to kill the accused "terrorist."

A week ago Attorney General John Ashcroft released El Zaatari's name along with 93 others who were charged with federal crimes after the aggressive anti-terror sweep spurred by the Sept. 11 attacks. But the U.S. attorney's office has offered no evidence linking the art student with any terror activities, and several law enforcement officials have admitted they don't think there is any. They defend El Zaatari's prosecution nonetheless, insisting he broke a federal law by carrying weapons on an airplane. Holding him without bail is necessary, they say, because he's a flight risk.

But his defenders insist federal officials are making an example of El Zaatari, and say he'd never have been detained in the first place if it wasn't a time when Americans look twice at young Middle Eastern men.

"Everyone knows he's harmless," insists Francis, who discovered that the young man he initially thought might be a terrorist came from the same town he did, Saida, Lebanon. El Zaatari turned out to be the nephew of Francis's high school principal, a courageous man who prevented marauding Palestinian militia men from kidnapping Christians like Francis from school, a few times receiving vicious beatings for his efforts. Now Francis is grateful for the chance to return the favor to young El Zaatari, even offering his house as collateral in an attempt to free the young man on bail, but so far his efforts have been unsuccessful.

"If he were connected to organizations or knew anyone it might be different, but he isn't," says an angry Francis. "In fact, his family has been victims of fanatics in Lebanon. It's time to let this poor guy go home."

That's exactly what El Zaatari says he was trying to do Oct. 28. Although he wanted to stay in the U.S., his father, a prominent Lebanese banker, had urged him to return home because of the angry backlash against Arabs in America the older man had seen on CNN. The son had been a little worried, too; for weeks after the attacks, friends say, he avoided leaving the house, for fear of the American reaction to an Arab-looking stranger. But he was emotional about having to leave his friends, says roommate Charles Piatt, and he worried that if the war on terrorism escalated he would not be able to return to America for a long time.

Piatt was one of five American friends who dropped El Zaatari off at Pittsburgh International Airport; he had even helped his friend pack, because he'd procrastinated much of the day and was in danger of missing his flight, Piatt recalls. The former art student breezed through two security checkpoints without a pause. But at the gate a Northwestern employee hand-searched El Zaatari's laptop case and found among pencils, pens, and other work supplies the disposable utility knife, commonly used by graphic artists. Facing a Middle Eastern man with an accent carrying an object that seemed comparable to a box cutter -- the Sept. 11 hijackers' weapon of choice -- the employee quickly alerted the FBI agent on duty at the airport. Piatt was shocked that night after returning home from the airport to hear his friend's name on the 11 o'clock news as a suspected terrorist.

"Anyone who's talked to Salam knows he's not what they made him look like in the news," Piatt said. "He's one of the most laid-back, peace-loving people I know."

Some of El Zaatari's problems were simple bad luck. Had one of the two metal detectors he passed through found the blade, it would have simply been taken away; because he was at the gate it was a more serious transgression. And before Sept. 11, it would have been legal for him to carry that type of knife on an airplane.

During the FBI interview, El Zaatari told the agent he had forgotten the instrument was in his bag and didn't even know it was now prohibited on planes. He had been carrying it with his other work supplies for months; in fact it had been in his bag two months before, when he had flown back to Lebanon to visit his family. When the agent asked if he'd known that the Sept. 11 terrorists had used box cutters, El Zaatari said no, a claim that was ultimately used against him, because the FBI later found magazine and newspaper articles about Sept. 11 in El Zaatari's luggage, which they say proved that he knew what weapons the hijackers carried.

FBI agents visited the house where Piatt, El Zaatari and other students lived in the days after the arrest. Piatt described his creative friend -- the two met sitting on their neighboring porches in the evenings, and found that they shared a love of movies and eventually worked on screenplays together -- and said that El Zaatari had been researching film schools to attend and hoped to eventually work in Hollywood. In fact, he had clipped the articles about Sept. 11 that the FBI found suspicious because he intended to make a documentary on the tragedy. El Zaatari had made a similar documentary years before, interviewing his friends about the Lebanese civil war; the film was later shown in Lebanese schools.

The FBI agent who visited Piatt asked if there were any other knives like the one confiscated at the airport in the house. "There are art supplies all around the house," Piatt said; all his roommates are involved in the arts. "In any room, there are art kits that have those types of knives." He reached into his coat pocket, he says, and produced two he had been using earlier in the day.

The FBI also asked why El Zaatari's flight to Beirut was booked through Detroit, which has one of the largest concentrations of Middle Eastern immigrants and has been home to suspected terrorists. Piatt was there when El Zaatari first made flight reservations, he said, and it was simply the first and least expensive flight the travel agent found. His friend had no special reason to travel through Detroit, Piatt said.

Piatt thought that the answers he and his roommates provided, as well as their descriptions of El Zaatari's character, would help the government realize that the young man in custody was no threat. "I expected them to do a background check and then let him go," he said.

Instead, the U.S. attorney's office indicted El Zaatari Nov. 1 on one count of carrying a weapon on an aircraft, a federal offense.

Supporters still didn't panic. Francis went to downtown Pittsburgh's Federal Building for El Zaatari's Nov. 5 bail hearing convinced the young man would be released from jail, and they'd work on his defense together. But although the pretrial report recommended that El Zaatari be granted bail with electronic monitoring and other close supervision, Assistant U.S. Attorney Constance Bowden asked for remand without bail, claiming there were no measures that could assure El Zaatari's appearance in court.

The U.S. attorney's office did not think El Zaatari was a danger to the public, she admitted in testimony, but saw him as a flight risk. She noted that his student visa was out of status, since he was no longer enrolled in school, that he was not employed, and that he "has no real ties to this country, really, has no reason being here." She also introduced as "relevant" the fact that he'd admitted to the FBI agent and to a pretrial officer that he smoked marijuana.

Still, Francis wasn't worried about bail. "She didn't put up any kind of good argument; I thought it was a clear victory," he said. "I thought he was going home with me that day."

But the judge agreed with the U.S. attorney that El Zaatari was a flight risk, and denied him bail. In an appeal, a second judge came to the same conclusion.

"I couldn't believe it," Francis said. "When they denied him bail, they had all the reports about him, they knew in their hearts that what he did was only a stupid mistake."

Since taking office Sept. 17, Pittsburgh-based U.S. Attorney Mary Beth Buchanan has promised that she would deal forcefully with terrorists, and since then she's had her hands full. Unbelievably, of the 93 cases Ashcroft has identified as being charged with federal crimes in connection with the Sept. 11 dragnet, 26 were in Pittsburgh. Twenty-two of those (mostly Arab men) were in connection with a false-license scheme uncovered in early October; El Zaatari was one of four other unrelated cases.

In a phone interview, Buchanan says that the government's treatment of El Zaatari is "an instance of the U.S. attorney enforcing the law, period."

When asked if she thought El Zaatari was a terrorist or involved with terrorists, Buchanan said that she "couldn't comment on that" because once someone is indicted, "normally, we don't say anything about pending cases." She firmly denies that El Zaatari is being tried because of politics or ethnic prejudice. "Mr. Zaatari has not been treated any differently than any other individual given the same facts and circumstances," she said. "If you had done the same thing, you would face federal prosecution, too."

But El Zaatari's criminal lawyer, Tony Mariani, says the government is guilty of selective prosecution -- that knives and other sharp instruments have been found on people in Pittsburgh International Airport, but that El Zaatari has been the only one charged with a crime -- and he's filed a motion to dismiss the case. "Mr. El Zaatari's prosecution is not fueled by his possession of a cutting instrument but rather by the fact that Mr. El Zaatari is of Middle Eastern descent," the motion reads. He has filed another dismissal motion on the grounds that the law itself is vague, and that the FAA announcement of increased security only mentioned that such "cutting instruments" would be confiscated, not that anyone would be arrested.

There have been some mixed signals from the U.S. attorney's office as to whether officials believe El Zaatari is involved with terrorism. Buchanan insists she can't make a statement one way or another, although in the case of the false licensing scheme, she was quick to tell the media that none of the men were suspected of terrorist ties. But she won't clear El Zaatari. "Normally, we don't say anything about pending cases," she said. "In a case that gets so much attention, if we are able to make comments, we do." She cleared the 22 false-license detainees because "there was great concern in the public about the incident," and because those people had been released on bond and were back in public. "It was appropriate to provide the information we did," she says.

But while Buchanan doesn't feel comfortable making statements about the El Zaatari case, others in her office do. At the bail hearing, Assistant U.S. Attorney Bowden said she and her colleagues "do not and have not indicated that we have any particular links with the defendant to terrorism." Another assistant U.S. attorney, Paul Brysh, was even more certain, telling the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette last week that none of the people arrested in Pittsburgh were suspected of terrorism or any connection with Sept. 11. Brysh confirmed the quote in a phone interview, and said the U.S. attorney's office does not believe El Zaatari has any connection with terrorists or terrorism.

Attorney Bob Deasy, who is handling the immigration side of El Zaatari's case regarding his out-of-status student visa, said that his client "was caught up in Ashcroft's sweep." Before Sept. 11, there was almost no way a client in El Zaatari's situation would have been denied bail, Deasy says. In fact, he almost certainly would never have been arrested: The INS either ignored students with out-of-status visas, or wrote a letter and asked them to come in and explain their situation. But because at least some of the Sept. 11 hijackers entered on student visas, cases like El Zaatari's are getting greater scrutiny, and many in his situation now have to leave the country.

That may well be El Zaatari's plight, but before that he's likely to spend at least two more months in jail, since his case isn't expected to go to trial before February. Piatt said his friend's spirits were a bit higher during their last visit, because El Zaatari had been allowed to make Christmas ornaments for the jail's tree. But Francis says the last time he visited El Zaatari, the young man spent more time crying than talking, worried about his future and how this ordeal was affecting his family. Francis' concern for El Zaatari extends beyond his possible trial: "He might be in danger when he gets back home. Maybe the Palestinians think he's a spy or that he came back as a CIA agent. That's what scares me."

Although Francis doesn't fault the government's initial scrutiny of El Zaatari, he said that this case has made him skeptical of John Ashcroft's claims that the war against terror is not being waged at the expense of individual rights. In fact, El Zaatari's inclusion on Ashcroft's terror-detainee list seems proof that his arrest and detention had something to do with politics and ethnic profiling. If El Zaatari had been a 70-year-old priest or an 8-year-old boy who had made the same mistake, it is very unlikely he would have been arrested and charged with a felony, much less detained without bail.

"I can understand why [the government] took it so seriously," Piatt said, "but when you know a person has no malice or malicious intent, you expect it to be resolved quickly."

"Since Sept. 11, people are scared," Francis adds. "I don't blame them for being scared. I'm scared too. But sometimes people react without thinking. That's the most scary of all."

Shares