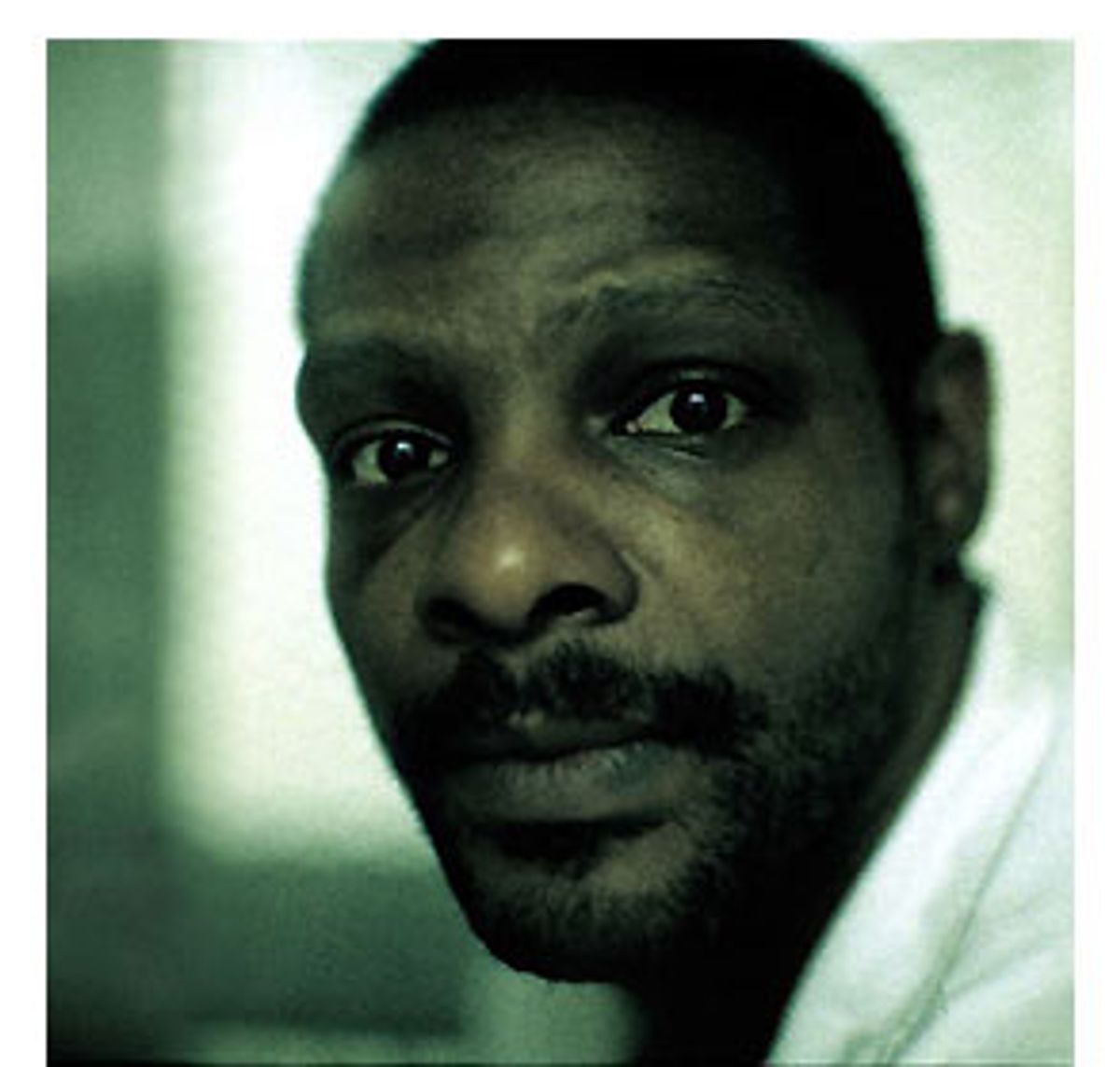

As the number of death-row prisoners exonerated by DNA evidence continues to mount, some innocent inmates are still being freed the old fashioned way, when new evidence emerges to implicate another suspect, or supposed witnesses recant their stories. But Joseph Amrine, a black man convicted by an all-white jury of killing a fellow prison inmate 17 years ago, still sits on Missouri's death row, even though all the witnesses against him now say he didn't do it, new witnesses have identified another inmate as the killer, and at least three of the 12 jurors who convicted Amrine, including the jury foreman, now say they think he is innocent.

Death penalty opponents say Amrine's case is among the most egregious examples of the flaws in the nation's capital punishment system. His legal appeals completely exhausted, Amrine's fate now lies in the hands of Missouri Gov. Bob Holden, a pro-death penalty conservative Democrat who has been authorizing executions at a rate of about one per month throughout his term, and who has yet to commute or even stay a single prisoner's sentence.

Amrine, now 45, was serving a short sentence at the Missouri State Penitentiary (now known as Jefferson City Correctional Center) for check kiting when he was accused of the October 1985 knife slaying of Gary Barber, a fellow prisoner. He is facing execution despite the fact that the three prisoners who testified against him at his trial have subsequently recanted their testimony. They say they were pressured by prison authorities to lie, and then rewarded for it.

The way Amrine's lead appellate attorney, Sean O'Brien, describes his client's legal odyssey might be darkly comic, if a man's life wasn't at stake. When the first two of the prosecution's three witnesses recanted their testimony, the federal judge hearing Amrine's appeal, Fernando Gaitan Jr., ruled that they weren't credible, because the third witness had not disavowed his testimony that Amrine was the killer. But later, after that third witness came forward to say that he too had lied at the trial, the same Judge Gaitan ruled that this recantation was not credible. The judge went on to muse that none of those recanting could really be believed because they were all prison inmates, and thus inherently not believable -- reasoning that of course could have been used to dismiss their earlier testimony against Amrine, but wasn't. Gaitan also ruled that he didn't need to reconsider the earlier recantations, in light of the third one, because he had already considered and rejected them, so they were no longer "new."

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, after describing Gaitan's rulings in a May 5, 2000, editorial headed "Executing Without Justice," asked rhetorically, "Should the state execute a person when no evidence is left standing against him?" But that appears to be exactly what Missouri is set to do. Amrine, who was featured in controversial Benetton ads spotlighting death-row prisoners in 2000, could be executed as soon as the governor signs off on a state Supreme Court death warrant, which could happen at any time.

Amrine's case is important beyond his own personal situation, because the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals actually used his appeal in establishing an important precedent limiting the ability of criminals to introduce new evidence of their innocence. A three-judge panel held that the testimony of other inmates who say they saw another prisoner, Terry Russell, kill Barber was not sufficient to require a new hearing, because the defense could have obtained that evidence at the original trial, through due diligence, but did not. Despite acknowledging that Amrine might well be innocent, the appeals court ruled that the witnesses who might prove that could not be heard.

Legal experts say that precedent placed a chilling new limit on death-penalty appeals. In plain language, it means there may be eye witnesses to a murder discovered after a trial, who were never heard by a jury, who can attest to a person's innocence. But if for some reason the defense overlooked them or failed to call them at the trial, the person should die anyway.

While experts disagreed with the appellate court's decision on that point, many of them back the panel's contention that the public defender in the case, Julian Ossman, failed to give his client the best possible defense. At the time of the 1986 Amrine trial, Ossman was the Cole County public defender. Six of his clients currently sit on death row, and two of his clients' death-penalty convictions have been overturned at the federal level, including one by the 8th Circuit, on the grounds that they had ineffective counsel.

Jurors say in Amrine's case, Ossman didn't introduce evidence to challenge prosecution witnesses, failed to interview and thus prepare defense witnesses before putting them on the stand, and made little effort at the penalty phase of the trial to provide evidence of mitigating circumstances against the imposition of the death penalty. Efforts to reach Ossman by phone were unsuccessful.

Now Larry Hildebrand, one of the jurors who helped convict Amrine, is adamant that the governor needs to grant a pardon in this case. "At a minimum he deserves a new trial," he says. "All the witnesses are saying something different now, and if they'd been saying what they're saying now, I never would have voted to convict him."

Hildebrand, a Catholic who says he supported the death penalty back in 1986, now says he opposes it, based in part on the Amrine case. "If we kill Joseph Amrine, we'll have killed an innocent man, and that would be the end of it," he explains. "Saying 'oops' at that point isn't enough!"

But Scott Holste, a spokesman for the Missouri Attorney General's Office, which has been defending Amrine's conviction against appeals for 16 years, says there is no reason Amrine should be spared. He says that the courts have ruled on the recanted testimony of the prosecution's witnesses, determining that those recantations are not credible. But he says that his office will not interfere with the governor's decision on Amrine's parole petition, unless asked for an opinion by Gov. Holden. "It's in the governor's authority to grant pardons, and that's a decision he has to make," Holste said.

Certain facts of the case are not in dispute. On Oct. 18, 1985, Gary Barber, Joseph Amrine and the three witnesses who testified against Amrine at his trial -- Terry Russell, Randall Ferguson and Jerry Poe -- were all in the prison recreation room, along with several other inmates. At some point, Barber was fatally stabbed with a knife. He briefly attempted to chase his assailant, then collapsed and died.

A prison guard, John Noble, did not see the actual stabbing, but saw the chase. He told other guards that the man running from the scene of the crime was Terry Russell, who was subsequently taken into custody and read his Miranda rights. There were other witnesses who claimed they actually saw Russell stab Barber, but for reasons that remain unclear, they were not called at Amrine's trial. (One inmate, Kevin Dean, was standing in shackles in the hall outside the courtroom, ready to testify for the defense that he had seen Russell kill Barber, but he was never called.)

Russell, after first claiming that he didn't know what had happened, changed his story to say that Amrine had been the killer. Amrine had killed Barber, Russell told authorities, because Barber had been claiming he had had sex with Amrine. Although other inmates insisted that Amrine was innocent, and that he had been seated at a table with them playing cards during the incident, two other inmates, Ferguson and Poe, later joined Russell in accusing Amrine.

Cole County, Mo., prosecutors chose to charge Amrine, rather than Russell, which was the first head-scratcher in the case. Only a week before the slaying, Russell and Barber had been in a violent altercation and had only just been released from segregated detention, which would seem to make Russell a more likely suspect. And while Russell still denies that he killed Barber, he nonetheless now admits he falsely accused Amrine of the murder because he had already been informed by investigators that he himself was the prime suspect in the case, and he wanted to deflect attention onto someone else. The ploy worked for Russell: His cooperation with the prosecution in the Amrine case earned him an early parole from prison, shortly after which he killed another man.

Ferguson and Poe backed Russell's story about Amrine being the killer. Now both say they lied about it, because they were being sexually threatened by another inmate, and that prison authorities and investigators promised them protective custody if they testified against Amrine. Ferguson, who also had felony weapons possession charges dropped by the prosecutor in return for his testimony against Amrine, reportedly began regretting his role in convicting Amrine as soon as the sentence was read. He immediately began writing letters to various authorities saying he had lied and wanted to straighten things out. But he was ignored until Amrine's appellate lawyers learned years later that he'd changed his story. O'Brien says Ferguson was recently tested by a polygraph expert, who found him to be telling the truth about his recantation.

Poe, who told prison authorities that Amrine killed Barber after he saw Amrine arrested for the murder, now says that he decided to offer false testimony in hopes of getting protective custody to prevent his being accosted by another inmate who was a sexual predator within the prison. But he took 10 years to come forward, and it was his recantation that Judge Gaitan ruled wasn't credible.

Missouri is one of the nation's leading death-penalty states, with 72 inmates currently on its death row and 55 executed since the death penalty was reinstated in 1989 (placing it third, in total number of executions, behind Texas and Virginia, according to statistics compiled by the Death Penalty Information Center.) It gained international attention when Pope John Paul II succeeded in getting one man's death penalty commuted by an appeal to the late Gov. Mel Carnahan in January 1999.

As a historical footnote, it was under then-state Attorney General John Ashcroft, now the U.S. attorney general, that the initial decision was made to fight Amrine's appeal, even though witnesses had recanted. Sean O'Brien, director of the Public Interest Litigation Clinic at the University of Missouri Law School in Kansas City, says that decision was vintage Ashcroft.

"While his fingerprints aren't on this case, he set the tone in the office," O'Brien charges, "that the attorney general's office is duty-bound to oppose all applications for relief, no matter how meritorious. In other words, they would continue to press for execution even if there is some doubt about guilt."

Cole County's current prosecutor, Richard Callahan, who took office a year after the Amrine trial, says that as a matter of policy, he has never brought a murder case where all the prosecution witnesses are jailhouse snitches. He says he would not have brought this particular case, and adds that the fact that all the witnesses have since recanted is "deeply troubling to me."

"There have been so many cases of jailhouse snitches being proven to have been unreliable, and here where you have all these recantations, you really have to question the original conviction," agrees Barry Scheck of the Innocence Project. "Even many prosecutors and judges have spoken out against the use of jailhouse snitches as critical witnesses, especially in death-penalty cases." Scheck notes that a large number of the 102 cases his organization has succeeded in overturning based on DNA evidence involved jailhouse witnesses testifying for the prosecution.

Shares