In the first couple of weeks after a Palestinian suicide bomber blew himself up outside our local pizzeria, killing three teenagers, I spoke with my parents every couple of days. Each time, one or both of them would make the same request: pack up the four children and "come back home" to Cleveland, Ohio. Four months later, I talk to my parents once or twice a week. We don't talk about suicide bombers or leaving Israel, but I can still hear it in their voices -- Come home, come home.

My mother and I e-mail each other every day. If I am late writing, she begins to panic that something has happened to me here in our settlement of about 6,000 people near Kfar Saba, located just a 10-minute drive from the Green Line, which separates the West Bank from Israel proper. It's the land Israel captured during the 1967 Six-Day War, land that Palestinians and Israel critics still refer to as "occupied" territory. We both watch CNN continuously, so if an news anchor or banner mentions any action near the Palestinian city of Kalkilya, located down the road from here, I make sure to call to reassure her that we are, indeed, all right.

I am not just a "settler" here. I am also easily identifiable as a recent American transplant. With my dearth of Hebrew language skills, my Midwestern accent, and my lack of Middle Eastern aggressiveness, Israelis in stores and on the bus often ask me how long I have been here. Almost two years, I now answer proudly (but also sheepishly, if I have failed to understand someone's basic Hebrew!). It does not take long for the questioner to do the math in his head. Are you crazy? he asks. Who would come here now with all of our problems?

In truth, we arrived exactly two months before then opposition party Knesset (parliament) member Ariel Sharon took his historic pre-Rosh Hashana stroll on the Temple Mount, touching off riots that led to what is now known as Intifada II. Because of this, nothing about our absorption into Israeli life and culture has been "normal."

Before we arrived, our community coexisted with its many neighboring Palestinian towns and villages. Our neighbors shopped at their roadside stands and drove on Route 55 -- the main artery into Israel proper -- with few concerns. Palestinians worked here in the construction industry, at the local supermarket and as city gardeners. Since we arrived, only bulletproof public buses are in use and all Arab workers have been banned from our community. A security fence has been erected around the entire settlement, and members of the community trained in firearm use do security patrol alongside the professionals. Last week my husband and I joined the dozens of residents here who have purchased bulletproof vests for use in the car.

We did not move to a West Bank settlement to help fulfill former Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu's vision of a "Greater Israel." Actually, as soon as we moved here, we knew we might be required to leave, should a peace plan force us to. And we would have done so, trying to be optimistic that it would be the right thing. But now, as the president of my homeland seems intent on pressuring Israel to give in to a "Palestinian state," and his secretary of state, Colin Powell, speaks of how the "settlements are a disturbing and destabilizing factor in our pursuit for a solution to the Middle East crisis" that will have to "be dealt with," the situation has changed. And I have, too. I'm no longer sure I'd be so happy to leave, or optimistic as I packed up our belongings.

We originally moved to this particular settlement to be with family. My husband's three sisters and their families, who moved to Israel 18, 12 and 10 years ago -- all live within four blocks of our small rented apartment. Our children are basking in the attention of their aunts and uncles and their 12 cousins. Our plan was simply to move to Israel, but we decided that our integration would be easier and the learning curve shorter if we could rely on close family nearby.

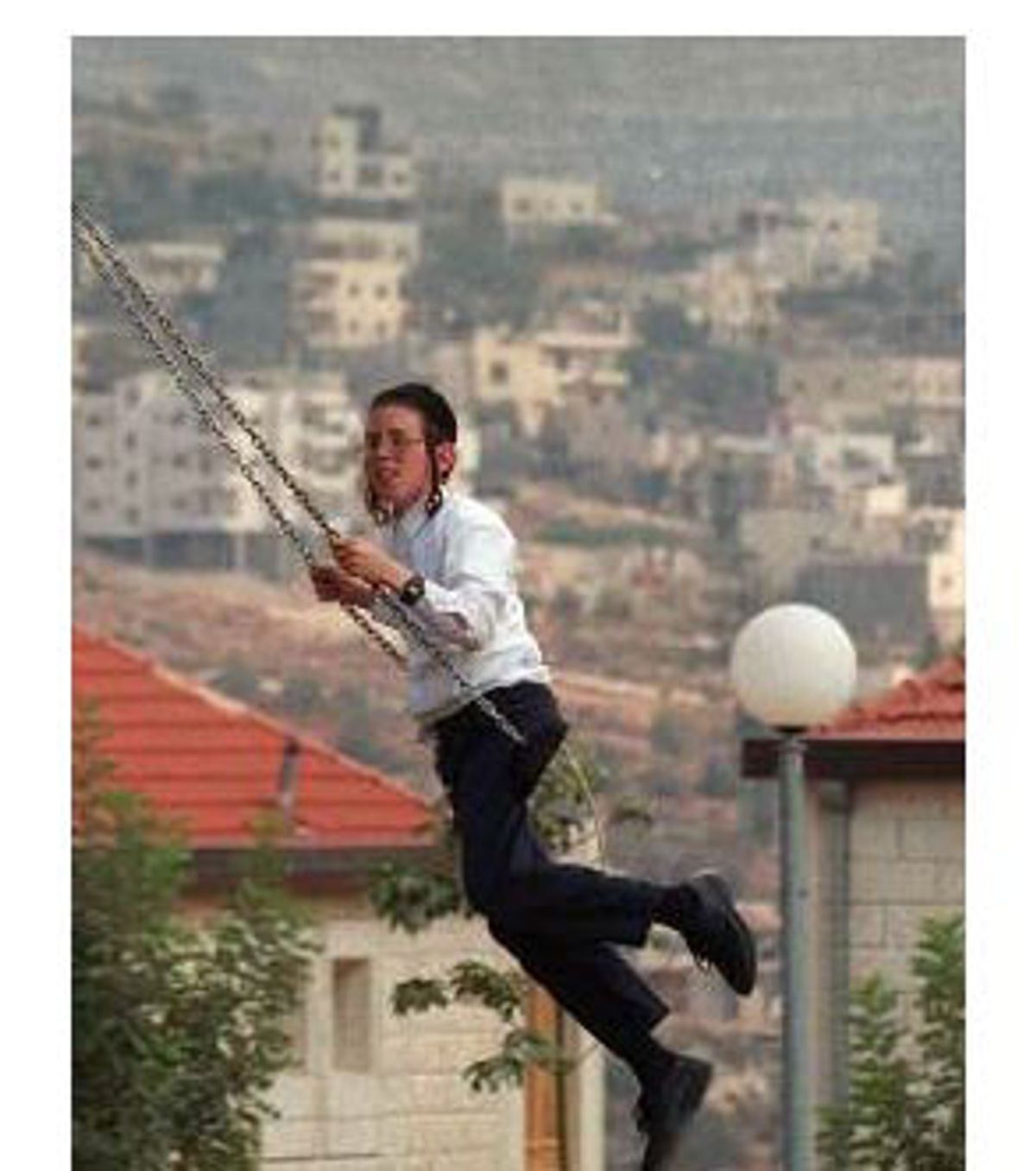

Many of the people who live here do not appear to have come for ideological reasons, but rather for a better quality of life. They've moved here for the reasons people usually move to the suburbs: The air is fresh, the greenery abundant, the children can play unsupervised in the community's myriad parks or walk themselves to a friend's house in safety. The school system that my children attend was recently ranked third in spending per pupil. Tax breaks for living here, which Sharon championed for years before becoming prime minister, also make buying and renting in the settlements much more affordable and attractive.

But our pastoral way of life has been shattered by almost daily reports of suicide bombers and attempted attacks that filter through the media and by word of mouth. When someone attempted to blow himself up inside a crowded supermarket in the settlement of Efrat near Jerusalem, just hours before the Sabbath, news of the thwarted attack (thanks to the quick thinking of one of the store's shoppers) hit the Internet at the same time it did the TV news. I read about it on our community's electronic bulletin board, since I try not to watch local TV news when my children are in the room. Many people in this community have friends in Efrat, and Saturday morning our synagogue buzzed with secondhand reports of what had taken place in one of the last Israeli towns to allow Arab workers inside its gates.

Through the attacks, I have felt a deepening connection to my neighbors, including those that have mourned death at the hands of Palestinian terrorists -- local deaths have included a mother of five children, three 14-year-olds, an elderly gentleman from the former Soviet Union -- just as I am connected to all Israelis who have suffered attack upon attack and who are fearful for themselves and their children every time they leave their homes.

It has also helped to put the little things into perspective. So what if my newly imported American stove does not work properly? So what if I can not find an Israeli brand of peanut butter that tastes halfway decent? So what if my daughter has brought home head lice from school again? People are dying out there -- mothers and fathers, sons and daughters. We had barely connected with our new, but in many ways only, homeland before we felt we were truly at war to defend it.

My father, a Holocaust survivor, actually entertained the idea of emigrating to Israel, instead of America, at the end of World War II and his escape from the Nazis. He and his two siblings eventually moved to Cleveland, but many of his cousins found their way to Israel and still live here today. One of my first cousins moved here from New York nearly two decades ago and lives just two blocks from my home here. And one of our third cousins lives right down the street.

My dad never made it to Israel because his relatives convinced him America was the promised land for Jewish refugees from the Holocaust. I think he forgot about his youthful idealism when I told him that I would be leaving his adopted homeland to move to the Jewish state. More likely, I think he was disappointed that after he went through being an immigrant in a strange country, learning a new language, building his own business, all so that he could give a better life to his children, one of them would choose to go through the experience all over again.

I wouldn't have imagined it either, growing up in Cleveland, where I took money to my synagogue's Sunday school each year just before spring to pay for a tree to be planted in Israel. I had a pen pal over there (actually a distant cousin). I knew that the room had to be quiet whenever Israel was mentioned in a news report.

But when I turned 10, my parents sent me to a Jewish overnight camp at the urging of our rabbi. The camp had a Zionist orientation, and I learned more about Judaism and Israel in my four summers there than I had in years of Sunday school and two days a week of supplementary Hebrew school.

At age 16, I spent six weeks in Israel on a summer teen tour. While everything started out feeling foreign, things soon began to feel very comfortable. Ruins that were centuries old stood alongside memorials to soldiers who fell in the modern state of Israel's many wars. All the people around us -- the kind ones and the rude ones -- were "my people." As we hung out on Ben Yehuda Street in Jerusalem on Saturday night and young people poured out of buses and taxis, I found a sense of belonging I had never felt before. I planned to return for other visits. I did not plan to spend my life here.

In college I affiliated with the campus Hillel, participated in activities in support of Israel, and contemplated a quarter abroad. I spent a quarter working at a newspaper in Wilmington, Del., instead.

My husband and I went out on our first date exactly one week after my graduation from Northwestern University and five days after I started working as a full-time reporter for the Cleveland Jewish News. Some time during our first date he told me he intended to one day make a permanent move to Israel. Did I ever see myself living in Israel? he asked. I liked the guy and wanted a second date. I said yes.

To his credit, during the first 10 years of our marriage, my husband always told me he would release me from my promise, and even as we planned our aliyah, he said that if I was unhappy personally or professionally there we could return to the United States. But we agreed that the best place for our children and grandchildren would be the Jewish state, where they would learn about their Jewish past, participate in their Jewish present, and prepare for their Jewish future. We would live in a place where the history they studied in school was Jewish history and where the national holidays we would celebrate together would be Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur instead of Christmas and New Year's Day. We would live in a place where our children would not worry about job discrimination because they could not work on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, and where wearing a kippah, or head covering, was the norm. Instead of watching Jewish history take place through a CNN camera lens, we would live it.

America and its special brand of democracy are still very important to me. What Americans think about Israel is also still important to me. And looking at world events, I carry with me a great deal of what I learned and believed as an American and a Jewish-American. But when I see polls showing that most Americans believe Israel should withdraw from the settlements in exchange for recognition by Arab countries, I wince. My fellow Americans, I think, don't really understand.

I came to Israel as a centrist, perhaps slightly to the right of center. I believed peace was possible, that we could live side by side with the Palestinians in their state -- on the Gaza strip and on the vast majority of West Bank land -- that was envisioned by the previous prime minister, Ehud Barak, and offered to Arafat in a deal brokered by then President Clinton at Camp David in 2000. On the day in 1993 that Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and then Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin signed a peace treaty on the White House lawn, I jostled with my fellow staff members at the Cleveland Jewish News to get a look at the historic event on the screen of our 13-inch black-and-white television. I believe I may have snorted when the two shook hands -- Rabin looked like he was getting a tooth extracted and Arafat looked positively triumphant -- but I bought into the pageantry of it all.

I still did when we finally moved here, three children in tow and one arriving a year and a half later. If Jews had to leave their homes in the West Bank, I thought, so be it. If we had to give up some of what we believe is land promised to the Jews by God and our forebears, so be it. The price of peace, I rationalized.

Yet with each passing week and month that I live here, my optimism about peace and living in peace with our Arab neighbors fades and my desire to remain here grows.

After every suicide bombing, Hamas or Islamic Jihad release a videotape of their "martyr" who talks on camera about why he, or she, has decided to become a human bomb. The videos are usually released to the Arab cable network, al-Jazeera, and picked up by Israel's television, which sometimes gives a running translation. I hear the venom in their voices and see their conviction that they are right -- and their belief that they will achieve paradise for their actions. I see the bomber's parents interviewed, usually flashing a victory sign and accepting congratulations from their neighbors and friends. And I realize that another generation of Palestinians has been taught to hate Jews and that their ultimate goal is to drive us all into the sea.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The Palestinian manager of the corner market always greeted me with a smile and had little treats for my children. The Arab man behind the meat counter at the local grocery store began working on my order as soon as he spied me coming up to the counter. The Palestinian owner of the gas station up the road always peeked into the car to see how quickly my infant son was growing and asked how we were handling the "situation."

I am sorry that those hard-working men have been banned from the community. On the other hand, my relatives and neighbors point out to me that those men may be fine people but if one of the terror organizations threatened the lives of their family members, there is no telling what they would do. I don't believe one of the men I know would personally become a human bomb, but if Hamas or Islamic Jihad threatened to kill their wives or children unless they eased an operative's way onto the settlement or into the store, I have a good idea of where their loyalty would lie -- after all, can I be sure I would act any different? Interestingly, most of the day-to-day contact between Israelis and Palestinians took place in the settlements, and those contacts were, for the most part, very good. Only after suicide bombers and gunmen began entering the settlements several months ago did those final contacts break off.

And in their absence, I will admit it: It becomes easier to think the worst of them.

On Sept. 11, My children were running around the house and I was attempting to get dinner started when my husband called me from the Petach Tikvah hospital, where he is a staff internist. "Turn on the news," he urged. I flipped CNN on just in time to see one of the four hijacked airplanes slam into the second tower of the World Trade Center. Before I knew it, my cynical side kicked in -- "Arabs," I nodded to myself.

I was ashamed of my knee-jerk reaction, but it was soon to be validated. And when I finally sat down with my kids to talk to them about what had happened, in a country where their grandparents live and in a city where we have many relatives and friends, it was their first reaction, too. "Was it bad Arabs?" my oldest, age 7, asked.

I e-mailed friends to extend my sympathies and make sure they were handling things emotionally. At the same time, I felt somewhat vindicated. Terrorism can happen anywhere, even in America.

When President Bush announced his intention to launch a war on terrorism, I cheered. But then, not only was Israel specifically asked to stay out of the war on terrorism, but -- as the United States bombed the stuffing out of Afghanistan, causing many civilian casualties in the process -- Bush also continued to urge Israel to negotiate with a known terrorist leader and to decry a limited number of Palestinian civilian deaths at the hands of Israel Defense Forces.

Most of the organizations and people who less than a month ago were calling Jenin a massacre now agree that it was not. Palestinian estimates of 500 dead have been revised to under 50. In desperation, the Palestinians dug up bodies from area cemeteries and staged mock funerals to bolster their claims (in one funeral caught on IDF surveillance cameras and broadcast on Israel television, the "corpse" fell off the bier and began running through the crowd, starting a panic). This is not a people that is ready to make peace.

Each time I get into my car to drive to another city for something as simple as a visit to the bank or for a new pair of shoes, I feel a flutter of panic and fear. As I put on my bulletproof vest and set my cell phone to be ready to auto-dial the emergency number, I often cannot believe that this is what everyday life is like. This fear and incredulity stay with me throughout my whole drive down Route 55, where I often see soldiers at the side of the road -- sometimes watching through binoculars, sometimes running and, last week, shooting over the heads of a group of Palestinian men gathering in a field. I felt the rifle discharge, I smelled the smoke of the gun! When I pass through the checkpoint at the Green Line I am sometimes disconcerted to find a soldier's rifle aimed right at my forehead, as it is at each driver's as he enters Israel proper, ready to halt his entrance if it is determined he can pose a threat to others.

As my fear continues to fester, it is rapidly turning into anger, resentment and hatred. I feel this even as I try to teach my children that not all Arabs are "bad Arabs," as their friends tell them. That many of the people living in the Palestinian villages that surround us are good, and have families that they love just like ours. But the way things are, I am having a hard time believing it. And I am not the only one here.

I would like to see the Palestinians live with dignity and autonomy. I would love to live in peace. Ariel Sharon has seen his share of wars against, and adversity in, the Jewish state. When he and the other old warhorses here have faith in a peace plan -- one that is not disfigured by partisan politics and wrangling -- I will put my faith in it. When I am asked to leave, I will leave. And I, like my fellow citizens both here and in the United States, will pray that a true peace has really come. But right now, I believe that if we do leave the settlements, the violence will only follow us.

Shares