American soldiers have closed the "Great Saddam" mosque in Tikrit and are standing guard over it, and the local population is not pleased. Groups of people gather across the road to glare at the heavily armed intruders. "It's a house of God and Americans are drinking whiskey inside," asserts one agitated older man.

Here in Tikrit and its environs, where Saddam Hussein has his roots, U.S. soldiers are emphatically not seen as liberators, but as occupiers.

There are reasons why people here are not celebrating the passing of the old regime. The town did well under Saddam. Many of its inhabitants served in the army or were senior government employees. Economically, Tikrit is definitely a cut above other regional capitals in Iraq. Shiny new government buildings and other public facilities, such as the mosque, add to its relatively wealthy image.

The Tikritis' privilege and dominance have led to envy and anger elsewhere in Iraq. "Saddam has been a curse for Tikrit," says a retired government employee who asks not to be named -- the fear of Saddam and his supporters is deeply rooted. "He gave Tikrit a bad name," the man persists nevertheless. "With his sons he did terrible things and we will be the ones to pay the price.

Everyone agrees that the Americans have been "tougher on Tikrit" because of the town's ties with Saddam Hussein. "Look, that is why they closed our mosque," a man says. Others are worried that people from elsewhere in Iraq may vent their anger at the old regime by attacking Tikritis, or by coming to loot.

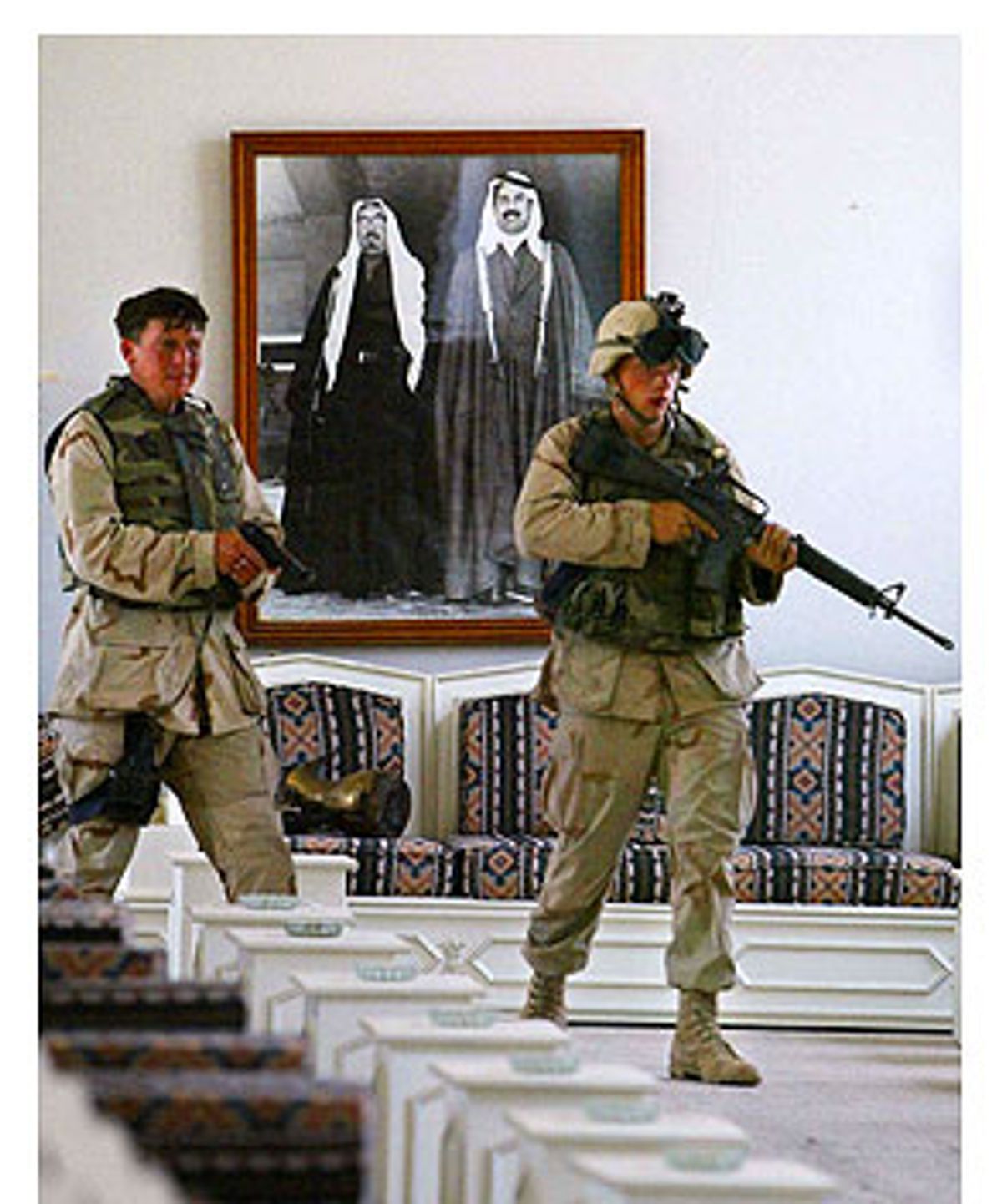

The most eye-catching place in Tikrit is Saddam Hussein's palace compound, a sprawling complex of palaces, palatial villas, guest houses, servants' quarters, garages, enormous generators, well-kept gardens and an artificial lake. The main palace sustained a direct hit from a U.S. missile and the whole complex has been looted, "but there's enough left to blow your mind," says an American soldier at the entrance who is, belatedly, standing guard.

The main palace seems to have had mostly a ceremonial function. It's the standard Saddam palace package: huge reception halls, large, ornately carved wooden doors, marble floors, gold fittings. Opulence drips even from the bombed ceiling in the form of shattered pieces of the crystal chandeliers. An Iraqi who is accompanying me stares in childlike wonder. "I have seen this room on TV," he says. "My father will never believe that I actually walked here."

A nearby palace with incongruous green-tiled roofs has more of a lived-in feel. Here, some expensive pieces of furniture are left: large beds, chairs and sofas, all in white and gold. In a medicine cupboard someone has left an antiseptic solution and a tube of cream for a skin condition. Near the entrance some large books have been pulled out of a bookcase. One of the leather-bound, gold-imprinted volumes bears the title: "Saddam Hussein's collected works, 1987-1988." Most other books turn out to be from the same series.

But in Tikrit, as in the rest of Iraq, Saddam Hussein's words are no longer law. In fact, there is hardly any law left to speak off. As they have elsewhere, the local tribal leaders have stepped in to fill the gap. Many people are gathered at the home of one of the most powerful chiefs, Khatan Khalaf Al Abdan of the Al Hadife tribe. Heads of the health services, technicians from the power plant, civil servants in charge of food distribution -- all have come to coordinate with the sheiks. Here too there is a steely determination to manage without the Americans.

"We do not want them here, they have come against our wishes and they are not behaving in accordance with their promises to bring freedom," says Al Abdan. He is seated in a large reception room of his own, done in a style known as "Louis Farouk," after the corpulent, ostentatious Egyptian king who was ousted by Gamal Abdul Nasser in 1952. The sheik, who is also a retired senior diplomat, explains why people are so bitterly opposed to outside help in getting rid of Saddam Hussein. "If I have a problem with somebody here in Iraq," he says, "then I can always redress it in some way, sooner or later. I know where that person's family lives, I know his tribal context, I know where to find him. The Americans are from far away and they are beyond the rules by which we live our lives."

The sheik's anti-American attitude is coupled with a fierce loyalty to Saddam's memory. He proudly tells the story of how the local commander of the U.S. forces came to him to demand that the people of Tikrit remove all statues of the missing dictator. "I told him that we would not. These statues are part of our heritage now, just like the ancient statues." The commander then said he would remove them himself, to which the Sheik says he replied: "You can do what you want, but you cannot make us do it."

The same defiant pride can be found among the people sullenly standing across from the Great Saddam mosque. Tikrit is probably the last city in Iraq in which buildings are still named after Saddam. In Baghdad, the locals have quickly rid themselves of that ever-present reminder of the leader: Saddam City, Saddam hospitals, Saddam Medical City are no longer. But in Tikrit many still seem willing to die for their distant blood relative.

"We had everything under Saddam Hussein," says one man. "Security, electricity, water, telephone. All gone now." He berates the Americans for not having fulfilled their promises. "Where are the democracy and freedom they talked about? Under Saddam Hussein we were free, we had democracy."

At this, some people in the crowd burst out laughing. "Come on," says one of them, "he's a foreigner but he's not stupid, tell the truth."

Tikrit is torn between those who remain fiercely loyal to Saddam Hussein and those who are now keeping their distance. "He is not from our tribe, he is a Naseri," says Hadj Taher Hassan Ahmed, a prominent member of the Hele'am tribe. There are five main tribes in and around Tikrit, and they are all related to each other in one way or another. "I'm only related to the president once you go back 10 generations or so," says Hadj Taher. "We never profited from our connection -- only the immediate family and others who were closely related did."

Somebody else gets angry at the attention that Tikrit is getting. "Just because somebody puts 'Tikriti' behind his name does not mean he is from here," he says.

"That is true," says Hadj Taher. "Saddam Hussein and his family are from Owja, not at all from Tikrit."

From Tikrit to Owja is a three-minute drive. "New Owja" sits huddled against Saddam's palace compound in Tikrit. It's a collection of gaudy modern villas that belonged to Saddam's immediate family and his inner circle. It is deserted: Most of its inhabitants have fled the country, people in Tikrit speculate. "Old Owja" lies just beyond it, the villas more modest, even shabby. They are also mostly empty.

Here too, Saddam Hussein had a palatial country home, at the end of a street of dusty lower-income housing. The house is looted and burnt: all that remains is a shining chrome kitchen machine on the pavement outside and a row of life-size terracotta dogs that served as pots for plants. In front of the residence, a totem pole shaped like a palm tree rises up three stories. It has images on it telling the story of Saddam Hussein's life to adulthood and presidency.

Outside the complex, a dented and rusty red Volkswagen Passat from the '80s pulls up beside one of the first villas in the street. Abu Gha'eb, a retired army officer who belongs to the Naseri tribe of Saddam Hussein, pushes open the gate to his villa and exclaims, "See, we were right to expect trouble." He points at his metal front door where bullets have made dents around the lock. "People think that because of our tie with the president we are rich but look around you."

Abu Gha'eb has only met Saddam Hussein once, in 1996, when he called a large meeting to solve a tribal problem. Saddam had to explain why it would be necessary to kill Hussein Kamel, his son-in-law, who had run away to Jordan and then foolishly decided to come back to Iraq. "Apart from that, I only heard of the president staying at his house here once, 10 years ago," says Abu Gha'eb. Saddam Hussein's sons Uday and Qusay visited a couple of times a year. "They were not nice people," says Abu Gha'eb. "But we should move on, it's history."

History seems to be on the mind of many people in Iraq as they contemplate the ruins of the country that Saddam Hussein has left behind. Friday prayers at Baghdad's Abu Khanife Nouman mosque started off with a historic reference too. The mosque used to be so pro-regime that on Fridays its sermon was broadcast on TV and radio. During the fighting a clock tower next to the mosque was damaged and the dome was also hit. People in Baghdad say that the Americans believed that Saddam Hussein had been hiding out at the mosque: Legend already has it that he gave his last prayer there before leaving town.

Imam Ahmed Al-Kubaisi, who just returned from exile in the United Arab Emirates, gave the Friday sermon. He started off with a historical comparison. The fall of Baghdad this time, he said, was the same as the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258 that ended the Abbasid Caliphate -- one of the darkest moments in Islamic history. "Now as then, the people of Baghdad were governed by unjust rulers." The other part of the message is more threatening to the Americans, though. What they are doing in Baghdad, he said, is the same as what the Mongols did, who pillaged the city before burning it to the ground, killed the caliph and his family and most other inhabitants, built a pyramid of the victims' skulls, and sold off the survivors into slavery.

Al-Kubaisi's speech, however far-fetched, succeeded in firing up the enthusiasm of the crowd for the large demonstration afterwards, planned by the venerable Islamist group the Muslim Brotherhood, operating under another guise. The demonstrators called for a withdrawal of U.S. troops and an Islamic state. They emphasized Islamic unity between Sunnis and Shiites and, in yet another historical fallacy, blamed the old regime for creating animosity between the two rival Muslim factions.

In front of Tikrit's Great Saddam mosque, one of the bystanders displayed more historical knowledge -- with an ominous message for the Americans. "Tikrit is more than just Saddam Hussein," said a sheik. "Saladin, who defeated the Crusaders, came from here. We will do the same again."

Shares