The rhythmic sound of thousands of Shia Muslims thumping themselves roughly on the chest reverberates throughout Iraq. Wednesday is the Arba'in, the 40th day after the death of Hussein, grandson of Mohammed, in the year 680 at Karbala. It is one of the holiest days in the Shia calendar, and for the first time in some three decades believers are able to make the annual pilgrimage commemorating this event the way their tradition demands it: on foot, with their banners held high with periodic stops to give voice to their grief over the death of Hussein. The old regime of Saddam Hussein, which treated Shiites harshly, forbade it. Now they are going in droves.

From all parts of Iraq the pilgrims have been streaming toward Karbala for almost a week -- openly, proudly and, despite the mournful occasion, joyously. For the first time since the fall of Saddam Hussein there is a clear mass popular expression of the relief of the people that the dictator is no longer in power. "Thank you, Bush!" many of the pilgrims shout, as they give the thumbs-up to the U.S.A. The religious holiday is turning into a huge festival of liberation.

The pilgrimage is taking place in a political maelstrom. The sudden and unmistakable joy expressed by most people may send a moderating signal to the more anti-American Shia religious leadership. Many of their followers are looking for political guidance during the holiday. "In Karbala, I expect the sayids [prominent leaders] to tell me how to behave toward the Americans," said one of the pilgrims before setting out for Karbala from Baghdad.

The other political aspect of the pilgrimage is the message that the sheer numbers of participants will send to the rest of the country and to the Americans. The clergy have called for record participation, and they may get their way. The eldest son of Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the most respected Shia authority in Iraq, hopes for 5 million people. That may be a gross exaggeration, but from the sight of so many deserted Shia towns and villages, it can't be totally dismissed. "Outsiders may consider it a Shia show of force; it really is not," he says. But other Iraqis, and the Americans, may not be convinced. At the very least it is a potent reminder that the Shiites are the majority group in Iraq.

Whatever its political implications, the pilgrimage itself has become a celebration of new freedoms. Earlier this week two brothers from Basra were resting at the Kathamiyeh mosque in Baghdad, where another descendant of Mohammed is said to be buried. They are determined to do the whole circuit this year, going from Baghdad to Najaf, the holiest Shia city, where Hussein's father, Ali, has his last resting-place, and then to Karbala.

"We have been doing it every year, even while it was forbidden," says the elder brother. "But we did a much shorter trip, only to Karbala, because it was very dangerous." They tell of roadblocks by the army and patrols to intercept the pilgrims. An uncle and a cousin went on the pilgrimage in the early '90s and were never heard from again, they claim. The brothers, like many other Shiites, decline to give their names because they are still not sure that Saddam Hussein is gone for good.

One man comes forward from among the crowd in the courtyard of the gold-clad and blue-tiled mosque to tell his story. In 1980 he attempted the pilgrimage for the last time and was arrested, he says. "Only for three days, but I will not describe to you how they treated me." Stories of the brutalities inflicted on the Shiites by the old regime come pouring out of the people. "We suffered the most under Saddam and we are the happiest to see him gone," say many.

In the village of Mahmudiyeh, between Baghdad and Karbala, a brightly colored tent welcomes weary pilgrims on behalf of the Shia Kretha tribe. Many of the long-distance walkers are asleep inside; others are being served tea and water outside. The tent belongs to Ahmed Yassin and his brother Abbas. Ahmed explains that the tribe has been helping pilgrims through the years, but in very different ways.

"We used to smuggle them past checkpoints, through our houses, our gardens and over the back roads," he says. "A pilgrimage like this, I have never seen before," he exclaims, referring both to the number of people and the exultant mood.

A little farther down the road, a student from Al Durra, near Baghdad, is walking toward Karbala with two female relatives, clad in black. "The road is safe," he says, "and we have the Americans to thank for it. They are our friends. They even said we could leave our weapons at home because they will defend us."

The Shiites say they still have many enemies in Iraq who are out to attack them. All along the route, a story is going the rounds that "Wahabites" (the ultra-fundamentalist Sunni Muslim faction that rules Saudi Arabia, and to which Osama bin Laden belongs) are poisoning pilgrims. Another rumor has it that eight car bombs have been detected and disarmed in Karbala.

It is not hard to see why certain factions might try to use the event to stir up trouble. Anybody, Sunni or Shia, who would like to provoke animosity between the Shiites and the Americans must be aware of the explosive potential of this occasion. If anything goes wrong, it could have disastrous long-term consequences for U.S.-Shia relations in Iraq. An incident from Israel's Lebanon war bears recalling. Although most people have long forgotten it, the Israeli army enjoyed relatively good relations with the Shiites in south Lebanon after the invasion of 1982 until an Israeli patrol blundered into the religious Ashura procession in the town of Nabatiyeh. Outraged Shiites stoned the Israeli trucks and set them on fire, and the Israelis opened fire, causing several fatalities. Relations never recovered, and in the end it was Shia militias that drove Israel from Lebanon.

Not that all Shiites are now 100 percent positive about the U.S. presence. Outside the mosque of Ali in Najaf, a group of men from Nasariyeh is eating lunch in a hurry before moving on to Karbala. "The American soldiers touch our women when they frisk them," some complain. "They look into our homes with binoculars and they show pictures from Playboy to our children," others chime in.

Still, even this relatively disenchanted group does not want to see the Americans gone just yet. "The war has barely ended, Saddam Hussein has not been found yet, and the country has to be helped on its feet," one of them explains. Another man, who had been complaining about the frisking of women, concedes, "We wouldn't mind the women being frisked if is being done by female soldiers." This reflects the attitude of the large majority of the people on the road. There may be some complaints, but by and large people regard the Americans as friendly and they want the troops to stay and finish the job.

This contrasts sharply with what some of the Shia religious leaders have been saying. Najaf is divided among several leading religious families who are vying for supremacy. Some are outright anti-American and pro-Iranian, others are sitting on the fence, but all of them want the Americans to leave as soon as possible. The leader who was backed by the U.S., Abdel Majid Khoei, was murdered earlier this month in the Ali mosque in Najaf. There are many theories about the murder, but the Iraqi National Congress, which is led by Ahmed Chalabi, also a Shia, says Khoei was killed because he was too clearly in the pocket of the CIA. The INC blames the CIA for associating with the wrong type of leaders in Iraq, including ex-Baath stalwarts.

The United States' association with Khoei and his subsequent murder has undoubtedly harmed the position of the U.S. in the power game going on in Najaf. The mood among the remaining players is foul. "We want the Americans out of here," says Mohammed Rudha, the eldest son of, and spokesman for, the 73-year-old Grand Ayatollah Sistani. The most respected Shia authority in Iraq, the grand ayatollah holds court in a matted reception room in a building on a dusty alleyway near the Ali mosque.

The Americans may have been instrumental in removing Saddam Hussein and making the free pilgrimage possible, says Rudha, but now they are behaving like occupiers. "Iraq does not want to exchange a dictatorship for rule by a foreign country." He then blames the United States for the evils that have befallen Iraq since the war, including the looting of the National Museum, the National Bank and other institutions. "The U.S. will be held accountable," he says. Sistani and his son are seasoned political players, though, and they know how to temper their rhetoric. "I will not say how long the U.S. can still stay," says Rudha.

He categorically denies that the pilgrimage to Karbala carries any political weight. "It is a purely religious affair," he insists. "My father, the sayid, has forbidden all political expressions during the pilgrimage. The only slogan that people are allowed to carry is: Iraq for the Iraqis, no to foreign rule."

The non-clergy political leadership in Najaf seems to be more in tune with the mood of the people. The Dawa party, which has opened an office on the outskirts of town, describes itself as Islamic, but it does not want the clergy to play a role in politics. It carried on its opposition against Saddam Hussein throughout the years of his regime and paid a horrendous price. "Thousands of our members have vanished," says Dawa spokesman Hussein Kathem, probably accurately. In records recovered in Baghdad, next to the names of countless executed prisoners are written the words "Dawa member" or even "family of suspected Dawa member."

Kathem, a tall, gaunt man in his 40s, says that he is a member of the party's military wing. He served two and a half years in prison in the late '80s because he was suspected of some kind of connection with Dawa. In fact, he reveals that his unit had at the time been planning to assassinate Saddam Hussein during one of Saddam's visits to Basra. The attack was aborted, but somebody got wind of some aspect of it and he was betrayed.

Despite some earlier pronouncements by the leadership abroad, Dawa is not anti-American, Kathem insists. He renders a remarkably mild judgment. "We used to have two main platforms: one, to get rid of Saddam Hussein and two, to establish a free and democratic Iraq. The Americans have done the first and we will now judge them on the second." He nods at the passing stream of pilgrims outside the office gates. "This is a happy sight."

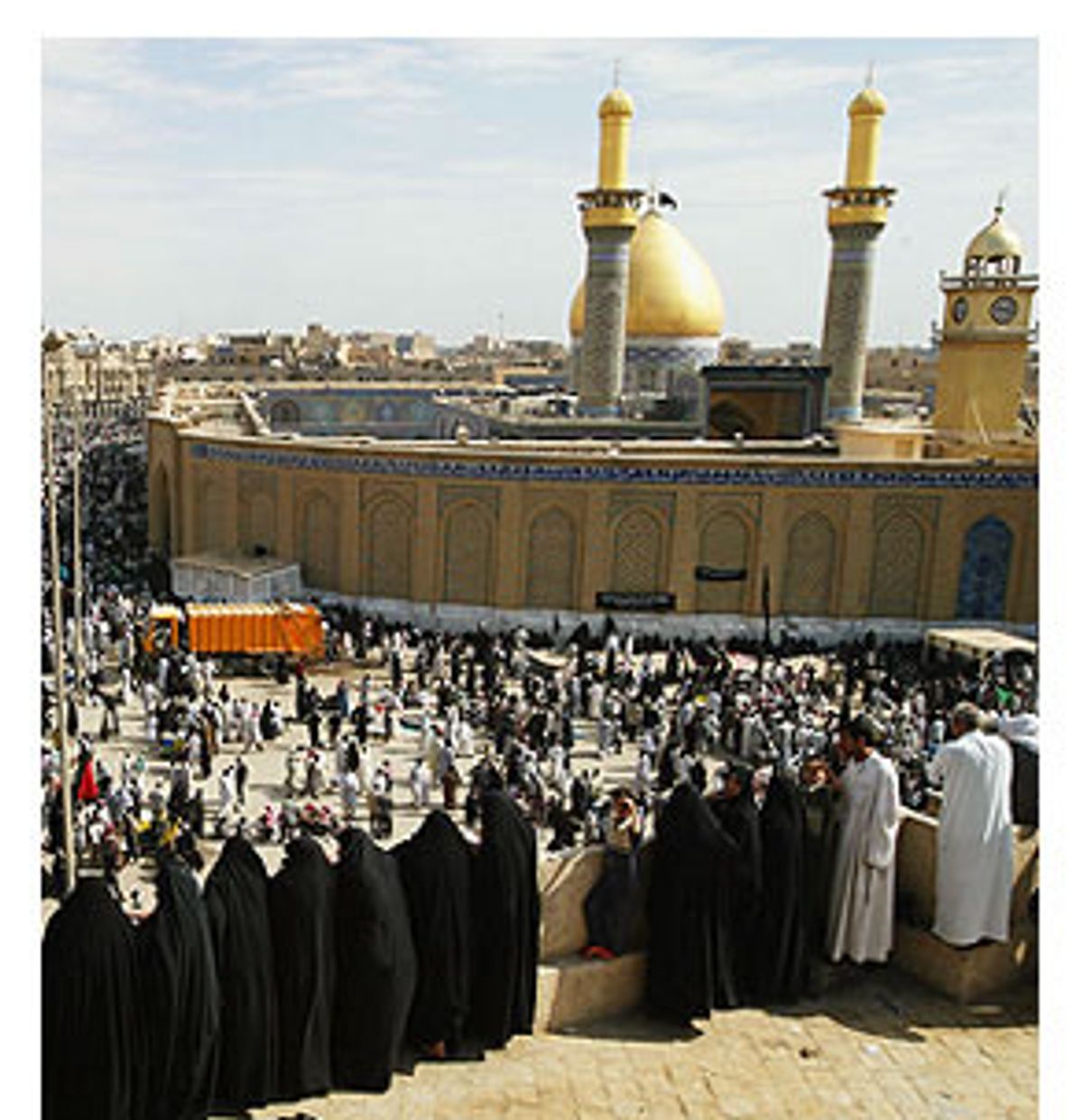

In Karbala, the excited crowd leaves all thought of politics behind. Full of religious fervor, groups from different parts of the country circle the ornate Hussein mosque, beating their chests rhythmically. "We only follow one revolution and that is the Hussein revolution," shouts one man. Thousands of Shiites thunder ecstatically: "Hussein, Hussein, look at us! We are your followers!"

Shares