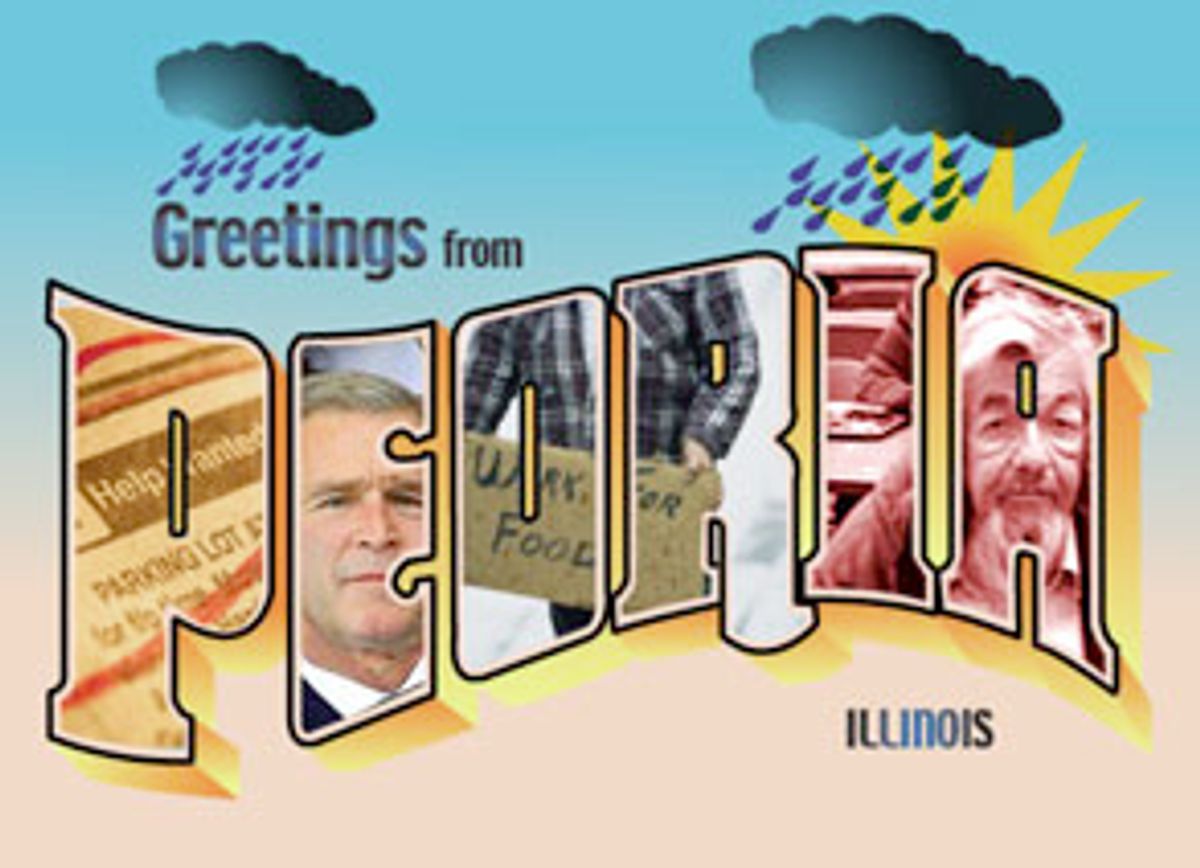

On a warm March afternoon just days before President Bush launched the invasion of Iraq, Robert Wood stood outside an unemployment office in Peoria, Ill., and fought a quiet war of his own.

For the last two years, Wood has been a discouraged job seeker. Until this winter he'd pieced together what he calls a "decent living," doing all sorts of odd jobs -- plumbing, roofing, drywalling. He was so proud of his ingenuity, he painted his name and home phone number on the doors of his rusty red Chevy pickup.

But through the winter and into early spring, the 41-year-old general contractor has been idle. If the economy seems to be in recession nationwide, its condition is more dire here in this city that voted for George W. Bush by a narrow margin in 2000. Various economic indicators prove the point, but Wood has a simple measure:

"There are no jobs," he complains.

Once there were plenty of jobs in Peoria. An industrial giant in the heart of the nation's farm belt, the city of 113,000 is situated on the Illinois River, linking Chicago to the Mississippi River. The location made it a perfect spot for heavy-machine manufacturers, distillers and stockyards. It grew from a French frontier settlement to the nation's "whiskey capital," when area companies paid more liquor taxes than in any other place in the country. Today Peoria is largely known as the headquarters of Caterpillar, the world's leading manufacturer of mining and earthmoving equipment.

But starting in the early 1980s, Peoria began to hemorrhage jobs. Factories reduced their operations or shut down altogether. Residents fled to the suburbs or to the Sun Belt. Empty storefronts line the streets of downtown, and many houses near the central city have been boarded up and abandoned. For years, methamphetamine labs were a problem that afflicted other areas, but in recent months a handful have been busted here.

When hard times hit, Peoria bleeds a bit more than the rest of the country. While the U.S. unemployment rate hit 5.8 percent in March, it was 6.9 percent here. In the last few years, the annual number of layoffs in the Peoria region has increased fourfold. In late March, two soldiers from a Peoria-based National Guard unit drowned while swimming across a canal during a reconnaissance mission in southern Iraq. Five days later, two more local guardsmen were gunned down by men on motorcycles in southern Afghanistan, about 70 miles west of Kandahar. Like most other traditional Midwesterners, Peorians overwhelmingly support the troops overseas, but skepticism about the war in Iraq has been widespread.

Peorians used to be cited as exemplars of the American disposition. The question "Will it play in Peoria?" originated during the days of vaudeville, when it was believed a show would succeed anywhere if it did well before a crowd of no-nonsense central Illinoisans. In the 1970s, White House aide John Ehrlichman used "Will it play in Peoria?" as a litmus test in setting national policies for the administration of Richard Nixon. But Nixon himself didn't care much for domestic issues; according to Richard Reeves' "President Nixon: Alone in the White House," the president belittled domestic policy as "building outhouses in Peoria."

Peorians in many ways remain an embodiment of the American heartland. It is a small city heavily influenced by the farm economy and by traditional values; its suburbs are relatively strong, and they're growing. But in every factory and on every street, globalization has fundamentally changed economic opportunities and risks, often for the worse. People are no longer as self-assured as they once were -- an uneasiness is pervasive. To Wood and many like him, the future looks bleak. And though Bush enjoys a high approval rating, both in Peoria and nationally, many here believe he needs to turn his attention to the economy if he doesn't want to meet the same one-term fate as his father.

In a series of interviews conducted here over the past two months, few Peorians said they believed Bush's $550 billion tax cut will fix what's wrong. Bush may be calling the tax cut a jobs program or an economic stimulus package, but many think it's tailored to the wealthy.

As the nation struggles to climb out of its economic doldrums, Peoria reflects a larger, decades-long trend bearing down on the American working class: With high-paying jobs lost to Mexico and other countries, secure positions at good wages are tough to find. If you're unlucky enough to lose your job, chances are your new employer will pay you much less than you earned before. And if you're not careful, you may wind up on a very slippery slope.

Take, for instance, Robert Wood and his wife, Lori. With their bills mounting, Robert said, it seemed they were arguing about everything -- who last did the dishes and where he left his boots after entering the house. On several occasions, Lori had even talked about a trial separation. After more than 10 years of marriage, she wanted to move the kids to her mother's in Florida, where she figured it would be easier to return to work.

When questioned on Elm Street, four blocks south of downtown Peoria, Robert Wood appeared understandably preoccupied. He related his story with an expression of disbelief -- circumstances were increasingly beyond his control. He needed a job, any job -- fast.

"I'm not afraid of hard work," he said, sounding a little frightened. "I'll lay cement, pick up trash, you name it."

The afternoon ended disappointingly. Classified as self-employed, Wood wasn't eligible for unemployment compensation. For the foreseeable future, there would be no money coming into his home.

Following a few minutes of conversation, he looked away and started to think out loud, listing everything he could possibly sell: his tools, his truck, exercise equipment he'd never used. He could apply for a state job-placement program, and he was told where to go for food stamps. He'd never been this desperate.

"I don't know," he said, shaking his head. "All I'm asking for is a job. But no one's hiring -- everyone's worried."

Like Richard Nixon, George W. Bush has shown a marked preference for foreign policy, though perhaps Sept. 11 and other events have forced that on him. While the U.S. has waged two wars in as many years, the American economy has shed more than 2.5 million jobs -- 500,000 of them in the past three months alone. Experts have been quick to cite various reasons. The conventional wisdom goes like this: First came the recession that followed the '90s boom, then the downturn after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and, finally, the climate of uncertainty created by the war on Iraq. Many economists have hoped a quick victory over Saddam Hussein would spark consumer confidence, which would in turn ignite economic growth. But in remarks before the Orlando, Fla., Chamber of Commerce early this month, Treasury Secretary John Snow acknowledged a flaw in that forecast: "The problem is not with the concern about the Iraq war -- the problem is the underlying weakness with the economy."

Since 1982, Bradley University economist Bernard Goitein has tracked consumer confidence in Peoria and nearby Pekin. When he arrived from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, Goitein was attracted to Peoria's low cost of living. "I could afford a nice Victorian home with all the original woodwork," he says, "and I could walk to work." He was also moving into an economic disaster area.

Pabst Blue Ribbon closed its brewery in Peoria Heights, leaving 1,000 people out of work. Then, long-term labor problems broke out at Caterpillar, starting with a seven-month strike in 1982. Cat had logged record profits in 1981, but its sales plummeted in the worldwide recession of the early '80s. It reduced its workforce from 36,000 employees to 17,000 -- and that set off a domino effect in Peoria's economy. The unemployment rate for the three-county metropolitan area was 16.3 percent. Tens of thousands left town.

"People were starting to panic," former mayor Richard Carver recalled in 1998. "Never was the need to diversify more evident."

Peoria responded with a strategy employed by many Rust Belt cities, attempting to spend its way out of the hole with big capital projects. Millions in subsidies and tax incentives went to persuade companies to stay on or to relocate to the area. That strategy has had mixed results. Some companies simply took the money and ran, sending factory jobs overseas. The firms that remained employed far fewer workers.

Today, Goitein says, Peoria has a more diversified economy. There are two large medical centers and several shopping malls. The city has become a major product-distribution hub, and an effort is underway to plant the seeds of a biotech industry. But most of the job growth has come in services, and the high-paying union slots are mostly gone. When Goitein moved here, Peoria was the second-largest city in Illinois, behind only Chicago. Now it's No. 5. Its metropolitan area totals more than 340,000 people, but that's still about 30,000 fewer than two decades ago. Manufacturing once accounted for 36 percent of the jobs; today it's half that. Caterpillar now has more management positions in Peoria than assembly-line jobs.

Komatsu, the Japanese manufacturer of mining and construction equipment, recently announced it will lay off 60 workers and shut its Peoria plant for three months, idling 310 employees. Many wonder whether the factory will ever open again. About 40 miles west in Galesburg, a Maytag refrigeration plant provided jobs to 1,800 people, or one of every 12 adults who live there. Last October, Maytag announced plans to move operations to Reynosa, Mexico -- across the Rio Grande from McAllen, Texas -- where workers make an estimated $2 per hour.

That closure has had ripple effects. When one of Maytag's suppliers, Freedom Plastics, shut down its factory in February, plant manager Chuck Eiben told the Peoria Journal Star: "Now it's just a matter of which vendors go first." The community may ultimately lose more than 5,000 jobs and $111 million in household income.

The economic downturn has also put the squeeze on Peoria's government, mirroring similar crises in cities across the country. Last year Peoria laid off city workers and cut back on services; this year it still faces a shortfall of nearly $1 million. The 225-member police department laid off 11 officers last year, and another round of layoffs may be in the offing. The fire department's resources were stretched to the limit by a late January blaze at an industrial cleaning business. Engines were pulled from one end of town to the other, leaving an entire half of the city without fire protection.

In November 2000, Peoria voted for Bush, giving him a margin of less than 1 percent over Democratic candidate Al Gore. Today, however, Goitein's index of consumer confidence is at its lowest point since the recession of the early '90s. Confidence normally spikes up in patriotic times: The first Gulf War provided a temporary boost, as did the events of Sept. 11, 2001. The conflict in Iraq may confer another rise, but any increase will have to overcome more than two years of bad news.

"The direction," Goitein says, "has definitely been down."

- - - - - - - - - -

One block away from the unemployment office is O'Brien Field, a new ballpark built for the Peoria Chiefs, a minor league baseball team affiliated with the St. Louis Cardinals. The privately financed $16 million stadium is part of a larger $23 million project just south of downtown. But when Peorians talk about the revitalization of their city, they usually point farther north to the downtown riverfront, a district of restaurants and gift shops. In warmer months, it hosts outdoor festivals. Caterpillar's seven-story headquarters is a block west on Adams. Currently there's talk of building a $60 million museum on a site once occupied by a Sears.

Despite all this money being spent on the central city, many locals still call downtown "seedy." Big Al's, a strip club, anchors a string of bars on Main Street. Located next to the Hotel Pere Marquette, the city's best hotel, Big Al's went upscale and turned into a multimillion-dollar enterprise when it was taken over in 1985 by Duane Cassano, a former welder laid off from Caterpillar.

A block away from Big Al's is Sullivan's Pub. Owner Mike Sullivan excuses the two shuttered nightclubs next door, saying they're "under reconsideration." Competition among the survivors on Main Street has grown fierce, he says.

On a Friday night, Sullivan's is packed. At the front of the room is a young crowd, mostly office workers from Caterpillar. They talk about their jobs and complain that the local paper lacks national news. The best they can say about Peoria is that there's no traffic. In the back of the pub -- past a table groaning with happy-hour hors d'oeuvres, sandwiches and ribs -- are the old-timers.

Mark, a thin bald guy in his early 50s, sits on a stool and nurses a bourbon on the rocks. He sells steel and remains "reasonably optimistic" about his business. But "there is no doubting these are difficult times," he says. "This is the toughest period I've lived through. There isn't anything that compares to it in my 30 years in the industrial market.

"Iraq has something to do with it. Global competition is part of it. But there doesn't appear to be an end in sight. Nobody knows what to do. Everything's in a complete state of flux."

Mark thinks the Iraq war was "probably the right thing to do," though he says it with hesitancy. "My son went to Iraq in 1991 and I'm very sympathetic to all of the families that have children over there." He supports the Bush administration "for the most part," he says. "I'm disappointed to see so many jobs leaving the United States, but I'm also sympathetic to the costs of the manufacturers."

On the next bar stool is Wayne Powell, a real estate agent. Times are still good for Powell's business. "There may be a bit of a slowdown, but we haven't felt the slump," he says. "I've been in real estate since 1961, and real estate is usually the first thing to fall and the first thing to rebound. But this time everything else is slumping and the real estate market remains strong."

But most of his business has moved to the suburbs: Germantown, Metamora, Dunlap. North of the city, he says, "they can't get the homes up fast enough." He's weathered the bad times, and these, he says, are not the same. "It lasted from 1979 until 1987 -- there was no work here, no building. Everyone was moving to Texas, Arizona, or somewhere to find work. A lot of people elsewhere in the country, they couldn't understand what we were going through, because they were doing well.

"If you've been out of work for a year, you'd probably say this is the worst time. But it's well-known that everything is much better off than back then."

Still, Powell is sympathetic to those having a rough time. He had been planning a winter vacation in Brazil, "or at least Florida." Then the war started, and his companion wanted to stay put. "I'm sure we weren't the only ones to change our plans," he says. "And our decision didn't affect just the airlines. It hurt the hotels, the rental car places, restaurants, souvenir shops. Everyone suffers."

When Ida Crall was 13, she'd take a bus every Saturday from Hanna City to downtown Peoria for singing lessons. That was in 1955. "Now you wouldn't see that," she says. "You wouldn't put your 13-year-old girl on a bus to Peoria by herself.

"My aunt lived on Antoinette Street, and we used to walk to a movie theater downtown. Or we'd go shopping at Bergners -- they had wonderful displays in the windows at Christmas. Sometimes we'd have lunch at the counter in Walgreen's.

"The town was a-boomin'," she says. "There were a lot of jobs -- Keystone Steel & Wire, LeTourneau, Hiram Walker. The jobs weren't hard to find, so no one crossed a picket line. That changed with the last strike."

The last strike started at Caterpillar in June 1994, and it lasted for 18 months. The United Auto Workers wanted a new contract; the company wanted concessions (some would say it wanted to bust the union). Throughout the strike, Caterpillar reported record profits. The company's retooled factories could be manned by managers, secretaries and salespeople. Many UAW members became scabs. The union had lost its leverage.

"You used to be able to strike -- you can't anymore," Crall says. "Everything changed when there were no jobs. Someone told my husband, 'I would walk over your dead body for a job,' and he was a friend of ours.

"A lot of people crossed the picket lines. My cousin was one -- he had to. People lost everything, their homes were foreclosed on, they had to file bankruptcy or move to another state. What would you do?

"When the jobs started leaving, people went with them. We knew a lot of folks who stayed on and had to take jobs that were paying half as much. People started losing faith and hope -- that brings in a lot of bad things.

"I guess I'm a fatalist. They say the future jobs are at the medical centers; then you look and see those jobs are paying $8 an hour. When you have most of your people making $8 an hour, often with no benefits, no health insurance, who's going to go to the malls anymore? Now Peoria's talking about building a museum when they're laying off police. Now, I know we need art, but we also need police and fire protection."

- - - - - - - - - -

In a glass case on the second floor of the Peoria Public Library, the front page of a faded newspaper tells of native son Richard Pryor's return to Peoria to film his 1986 autobiographical story, "JoJo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling." For 15 years afterward, a fight was waged to name a street after Pryor, but city officials were reluctant. His mother was a prostitute, and he was raised by a grandmother who ran brothels on the South Side. Then there was the matter of Pryor himself. Noted for his angry comedy routines and inspired use of profanity, he had always painted an unflattering portrait of his hometown. In 1980, he suffered serious burns while freebasing cocaine. Nevertheless, two years ago, a section of Sheridan Road was finally named after him.

"He's probably done more for Peoria than anyone," says Millie Hall, a petite black woman in a knit cap, as she arranges items in the display case. "He did his 'JoJo Dancer' here -- that brought in money. He's given money to Bradley University. Of course, I can't condone his drug use, but now he doesn't either -- he's stuck in a wheelchair with a bad case of multiple sclerosis."

Hall is taking down an exhibit marking Black History Month. She's the curator of the Garrett Collection at Bradley University. In 1948, Romeo B. Garrett became a professor of sociology and the first African-American to receive a master's degree from Bradley. Hall was later Garrett's research assistant.

She came to Peoria from Arkansas in the late 1950s, when, she recalls, five cousins were killed after a pair of white men set their house on fire: "I think one of the guys did two years in prison. I don't think anything happened to the other guy." She moved in with an uncle who had a job at Caterpillar.

But she found segregation still existed in Peoria -- blacks were confined to certain neighborhoods and public schools -- and in the early '60s she got involved in protests for open housing and employment, organized by John Gwynn, head of the local chapter of the NAACP. Today a little more than 20 percent of the city's population is black, and Peoria has a park and a street named after Gwynn.

Hall introduces Dolores Klein, a short, elderly white woman who's busy putting up the next exhibit in the library, this one for Women's History Month. The two have been friends since meeting at an open-housing protest in the 1960s.

Klein is a former president of the local chapter of the National Organization for Women. She notes that NOW founder Betty Friedan is also from Peoria, but Friedan left town in the 1940s.

Both women consider these to be particularly trying times. Prejudice is no less harmful, though it has become less overt.

"We may have passed some laws, but just because you see blacks and women taking advantage of opportunities doesn't mean the struggle is over," says Klein. "Right now we have someone in the White House who wants to please the people who elected him. If he gets to nominate two justices to the Supreme Court, an awful lot of things will be rolled back. That's a frightening thought.

"The economy is also getting very scary, and we're fighting wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. We can't seem to get along here -- I don't know how much time we have to stay over there."

In Peoria, as in other American towns and cities, a very scary economy brings the kind of street crime often associated with economic dislocation. That's nothing new -- in the old days, Peoria was known as a wide-open river town where Al Capone and other gangsters had important business.

"We've always been considered a high-crime area for our population numbers," says Sgt. Jeff Adams, head of the Peoria Police Benevolent Association. Adams has been a Peoria policeman since 1978. The greatest change he's witnessed in that time has been the rise of street gangs, "an entire subculture that doesn't think the rules apply to them." That subculture is financed by a lucrative drug trade. Though "the drug of choice is still crack cocaine," Adams says, methamphetamine has started to make inroads. Two years ago, he didn't see that drug in Peoria, but in the last year four meth labs have been busted.

"The problem is nothing like in rural areas west of here," he explains, "but it's a bigger headache than crack. The drug causes people to be delusional, violent and paranoid. People can be up for days. Houses burst into flames, people get asphyxiated. It's just a giant pain in the butt."

It also strengthens the grip of street gangs. "The gang culture may have come from Chicago, but now we have our own gangs -- they're very well entrenched," Adams says. "There was once a newspaper article that claimed the gangs had become the town's No. 1 employer. I don't personally believe that, but that's what the paper said."

At the bottom of Peoria's War Memorial Drive is a secondhand store run by Goodwill Industries. The store looks out over the riverfront, and its parking lot faces wooded bluffs to the north. Jake and Betty Leunz, a couple in their late 50s, hold hands as they walk toward their dented blue Ford. Jake is tall and gregarious; he sports sunglasses and a bushy black mustache. Betty is milder. She laughs easily as she brushes her shoulder-length white hair away from her eyes.

"I met Betty while hot-rodding down Main Street," Jake says. "That's what everyone did in the early '70s. We were the 'American Graffiti' couple. It was love at first sight."

Betty smiles and rolls her eyes. "He's a very sweet man," she says.

"Things were so much easier back then," Jake says. "After we got married, I worked at jobs where I made $5 to $7 an hour, but our rent on a nice little place was $65 a month. Now the kids today -- how much are they getting paid? $5 to $7 an hour."

"I don't see how young people can make it," Betty says.

The couple had two kids, and Jake started a business. For 11 years he owned an auto body shop. Six years ago, after Betty had a brush with cancer, they decided to cash in their chips. Jake sold his business and they paid off their house. It was all part of a larger plan to live cheaper and more fully.

"The first thing we did was get rid of our $35,000 cars," Jake says. "We had two of them. We sold our Isuzu with the leather interior and got this here 1990 van. We hear the economy's bad, but it no longer makes a difference to us."

Now Jake sells his abstract paintings on eBay. Since he's a self-taught painter, he markets them as "outsider art." "People around here don't want to buy a painting unless it shows a barn," he explains.

It may sound as though Jake and Betty have been truly liberated, but they have one problem: They don't have health insurance. If Betty has any beef with the federal government, it's that the healthcare system is so reliant on insurance: "My sister had lupus, and she spent eight days in the hospital. The bill was $66,000! Jake just got two pairs of glasses at Sam's Club for $90. I asked why it was so cheap, and they told me, 'We don't take insurance.'"

But don't expect the Leunzes to pick up the cause of national healthcare, much less write a letter to their congressman -- they've dropped out. "What can you do about it?" Betty asks. "We just have to rely on more powerful men to make the right decisions."

"You know who I liked?" Jake chimes in. "Jesse Jackson -- I listened to him for two hours and I thought, if someone ever did this, it would be great! But it could never happen."

- - - - - - - - - -

Two blocks north of Caterpillar's headquarters is a five-story painted brick building constructed in 1925. It's just across the highway, but it might as well be in another world.

The white paint flakes off the outside of the Peoria Labor Temple, which houses various union locals belonging to the AFL-CIO. Steve Capitelli sits behind a desk in Room 12. Of all the union locals in the building, his is the only one that's growing.

The Service Employees International Union Local 880 represents 14,000 home healthcare employees. In the past two years, its ranks have swelled by more than 4,000 workers, all of them making little more than minimum wage. Many could be counted among the working poor.

"The folks we represent are employed through the state agencies," Capitelli says. "Even though they're providing healthcare to others, they don't have health insurance themselves. They also get paid between $5.50 and $7 an hour."

The 49-year-old organizer first joined a union when he was on the assembly line at Fleming-Potter, a Peoria printer of labels and packaging. When he got caught in a company downsizing -- "me and a lot of other people" -- he decided to pursue labor organizing full time.

SEIU Local 880 has been in Peoria since 1995. When Capitelli took his job with the union, he looked at the local's members and felt as though he was starting from scratch. But now he thinks their struggle represents the future for labor unions. "Working with this type of socioeconomic workforce is what labor is all about -- we're fighting for basic human-dignity issues," Capitelli says. "It comes down to the workers recognizing they have strength in numbers."

Just this year, Illinois' new governor, Democrat Rod Blagojevich, handed the union a major victory, granting collective-bargaining rights to its members. "That's the first time this has ever happened," says Capitelli. "We've won raises along the way, but now we're in a position to sit down together at the table."

While Peoria has always been a strong labor town, it has also favored Republicans. Capitelli attributes that to a "heavy rural influence," but now he's noticed a larger shift taking place. "Peoria County and the city have been going heavily Democratic -- the majority of officeholders are Democrats."

SEIU has already come out in favor of Blagojevich's bid to raise the state's minimum wage from $5.15 an hour to $6.50. The median age of a minimum-wage earner in Illinois is 31, and 41 percent have two or more children.

The union also opposed the war in Iraq. "And most of the labor folks I've talked to have some very serious questions about the wisdom of it," Capitelli says. "Personally I think it's a huge waste of our resources. And for the first time in our history, we're an aggressor nation. Yes, Saddam is a bad guy, but who appointed us God to go after the bad guys? When does that end? The administration has never answered the most basic question: Why now? After keeping Saddam in a box for 12 years, why now? We couldn't get Osama bin Laden, so we're going after Saddam?

"Now that we're doing it, I want it to be successful, but I think it was a mistake. Bush will spend $75 billion as a first installment, and he still wants to give his friends tax breaks."

Capitelli believes Bush's tax cut will aggravate the federal budget crisis, making it clear the cost of the Iraq war will ultimately be borne by the little guy. In a sea of red ink, social welfare programs will have to be reduced or eliminated. "The irony," he says, "is the veterans will return home to find their benefits cut back.

"I'm just very suspicious of the administration's motives. There's another agenda Bush and his friends have got, and it's not a good one."

- - - - - - - - - -

Ida Crall's husband, Willard, is a survivor. For 36 years, he's worked at Caterpillar and remained a member of the UAW through every boom, every bust, every strike, and all the backstabbing and bitterness in between. His union local once had 23,000 members but now has 5,000, and he's left wondering what good has been accomplished.

Willard Crall moved to Peoria from Missouri in 1967, when he was 17 years old and fresh out of high school. He took a job at Cat's East Peoria plant, cleaning oil drums. He was quickly promoted to a forklift operator in tools and supplies, then truck repair. With each new position came a pay increase. Finally he was picked for the boiler room, and that brought not only a raise but also all the overtime he could handle -- two out of three weekends and every holiday.

When the UAW's last strike ended in 1995, Caterpillar closed plants, and boiler rooms were updated to natural gas. There were once 160 boiler-room operators in Crall's UAW local; now there are only three union guys left: Crall and his buddies Buck and Len. "We watched our kids grow up," Crall says, "and now we have grandkids."

Every week in recent years, he's watched semi trucks filled with parts coming up from Mexico. Two years ago Caterpillar hired an outside contractor to take over the boiler room. Since then, Crall has been training its nonunion workers to take over his job. At the age of 54, he'll be officially retired this summer, and though he'd guessed this day was coming, that hasn't made it any easier.

"I'll have to find something to do," he says. "All I've ever done is work."

He's worried, too, about the future for his two sons. At one time he advised them to get into the apprentice program at Caterpillar. "They both said, 'No way in hell. Why would I want to save for three years to survive for six or seven months while I'm out of work?' The point of the union was, you sacrificed for the good of the next guy. Today people don't really care about the next guy."

His son Michael has become a vocal political conservative. "I call him 'Little Rush Limbaugh,'" Crall says with a chuckle. "I really don't think that Michael is mine." Michael recently quit his job as a car salesman to return to school to become a history teacher. He's moved back into his parents' house.

"Somewhere something went wrong," Crall says. "People are working two jobs, and their wives also have to work just to make ends meet."

In Iraq, Crall believes, "Bush is now finishing what his daddy started. I have no problem with that, but I'm not impressed. Sooner or later somebody's going to have to put a foot down to keep jobs in this country. Our government needs to help families and create jobs at decent pay."

Shares