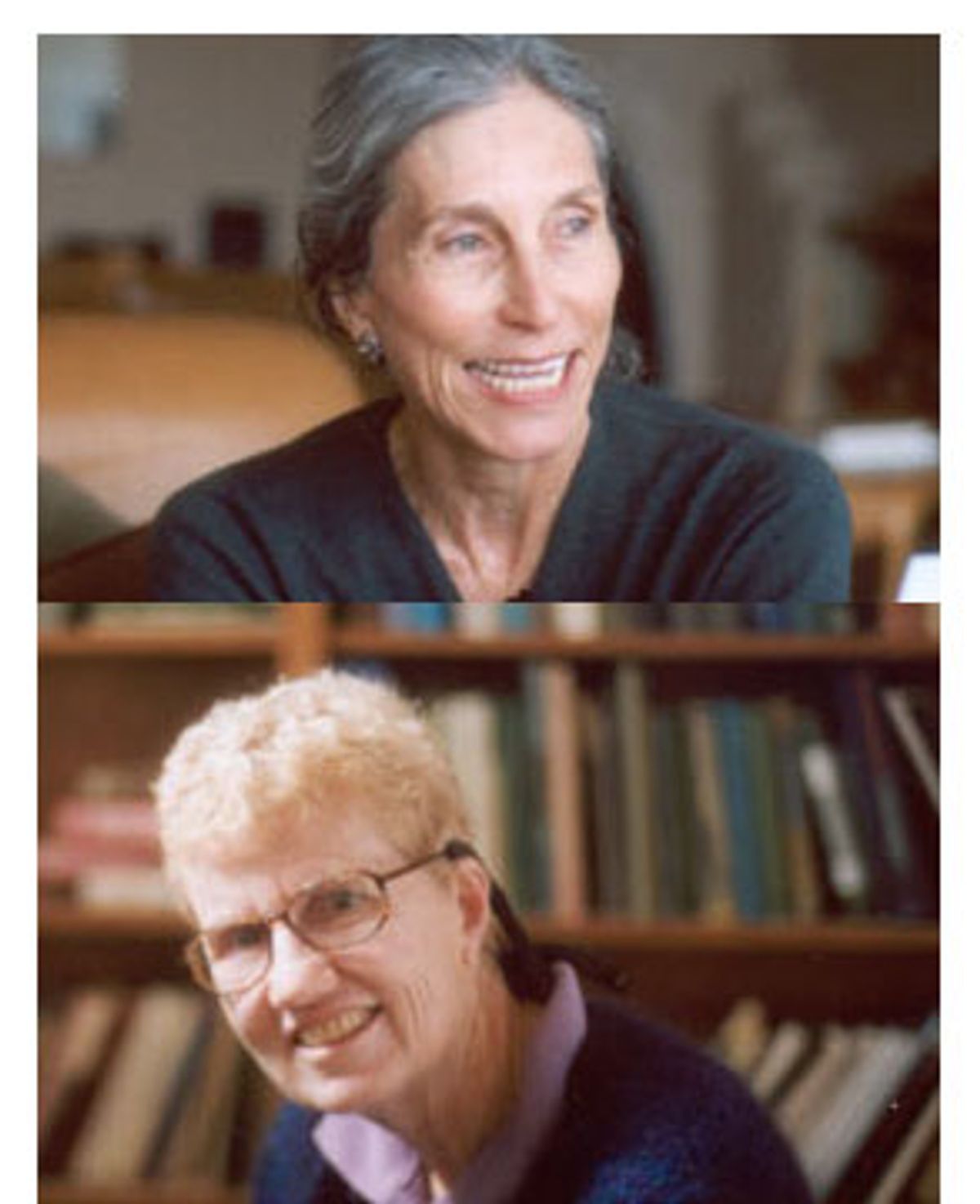

Eight and a half months ago, Jane Roberts and Lois Abraham were strangers, but both were equally outraged by President Bush's decision to freeze $34 million allocated to international family planning. Working separately, they sent out e-mails to everyone they knew, asking them to donate a dollar and pass the message on.

People did pass it on. Soon, Roberts and Abraham learned about each other and joined forces to form 34 Million Friends. On May 1, after ceaseless e-mailing, letter writing and phone calling, they held a press conference in Manhattan to make an announcement: They'd raised their first million. One hundred thousand people, most of them Americans, sent in donations to try to replace the money their government withheld.

It all began last July, when Bush caved in to pressure from the religious right to deny the United Nations Population Fund, or UNFPA, the $34 million Congress had allocated to it. Bush himself had requested $25 million of that funding in his budget proposal, but he was later persuaded by the claims of the Population Research Institute, a tiny group opposed to family planning, that the fund supports coerced abortions in China.

The Population Research Institute is a shadowy Virginia-based organization dedicated to "stopping human rights abuses committed in the name of family planning, and through research and education to dispelling the myth of overpopulation." Its Web site contains a variety of odd theories about global population control programs. Among them is the idea that the high incidence of HIV/AIDS among African women is the result of "the targeting of women and girls for invasive contraceptive, sterilization and abortion procedures by so-called Sexual and Reproductive Health programs." Rep. Chris Smith, R-N.J., a longtime PRI ally, called members of PRI to testify before the House, giving its charges a measure of legitimacy in right-wing circles.

The United Nations, England and the Bush administration itself have all sent delegations to China to investigate the allegations, and all have found them baseless. The administration's own team reported, "We find no evidence that UNFPA has knowingly supported or participated in the management of a program of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization in the PRC [Peoples Republic of China]. We therefore recommend that [the] $34 million which has already been appropriated be released to UNFPA."

Bush cut the funding anyway. As a result, the UNFPA was forced to cease family planning programs in rural Kenya, and to curtail obstetric training for doctors in Bangladesh and for midwives in Algeria, among other cutbacks. The agency estimates that the $34 million could have prevented 3 million unwanted pregnancies, over 7,000 maternal deaths and 1.2 million abortions.

Reading about what Bush had done, Roberts, a retired French teacher from Redlands, Calif., sent a letter to her local newspaper asking, "As an exercise in outraged democracy, would 34 million Americans please send $1 each? This would right a terrible wrong." She later e-mailed everyone she knew with the same request. Meanwhile, Lois Abraham, an attorney in Taos, N.M., e-mailed 40 people, mostly other lawyers, asking them to donate a dollar to UNFPA and to forward the information to their friends.

Both contacted the fund to tell them what they were doing, and officials put them in touch with each other. Soon, communicating via e-mail, they'd launched 34 Million Friends of UNFPA. The idea, Roberts says, was both to make up for the lost money and to show that the country supports international family planning even if the president doesn't.

The first envelope arrived Aug. 12. More and more started coming; soon there were around 200 a day. A donor in Maine who wanted to remain anonymous sent a check for $25,000. Someone from Canada sent $18,000. Yet many of the envelopes contained just a dollar bill. A woman from Riverside, Calif., sent a dollar wrapped in a pink sheet of paper saying, "Here is my contribution to the effort to replace the money denied by my government." A check from Boyce, Va., arrived with the note, "A small contribution from one person who is ashamed of President Bush's refusal to honor his $34 million commitment." Because the 34 Million Friends campaign has no staff and no overhead, every cent contributed has gone to family planning programs in the Third World.

The donations are a humanitarian gesture, but they're also a protest. Tim Wirth, president of the United Nations Foundation, a nonprofit group created by Ted Turner to support the humanitarian work of the U.N., said at the press conference that Roberts and Abraham are "helping Americans take back our government. This is a metaphor for a much broader set of questions."

Yet what Roberts and Abraham have accomplished is far more than metaphorical. At the press conference, they, along with Thoraya Obaid, the executive director of UNFPA, announced how the money would be spent. In Timor, it will be used to equip the country's only two hospitals that provide emergency obstetric care with two-way radios, train three doctors to perform Cesarean sections and buy 80 motorcycles for midwives so that they can reach rural areas. In Rwanda, it will buy ambulances and HIV/AIDS testing kits. In Eritrea, it will train 1,000 health assistants in basic emergency care. It will also pay for similar programs in Ghana, Mongolia and Bhutan.

Perhaps most significantly, half of the money will be used to fight fistula in the West African countries of Mali, Senegal, Nigeria, Benin and Malawi. One of the most devastating of all pregnancy complications, fistula has been eradicated in the West, but it continues to plague millions of women in Africa. The condition occurs when a woman suffering obstructed labor is unable to get a Cesarean section and her rectum, urinary tract and vagina are ruptured. Usually the baby dies and, if the woman survives, she is left torn and incontinent, often shunned by her husband and unable to work.

In February, at the invitation of UNFPA, Roberts visited a place called the Oasis in Bamako, Mali, which treats women with fistula. Without surgery, Roberts says, the women live in "perpetual incontinence and misery. They're quite isolated and quite depressed. Sometimes these fistulas are so bad that they can't be repaired. Other times it takes more than one surgery." However, 90 percent of the time, an operation can cure a fistula sufferer. The operation costs $350. The dollars sent by thousands of Americans through Roberts and Abraham's efforts will help pay for many of them.

More, of course, is still needed. This year, Canada and Europe raised their contributions to UNFPA by $18 million to try and cover the American shortfall, but crucial programs are still under funded. While Roberts was traveling in Africa, Abraham went to Nicaragua. She visited the Casa Materna in Matagalpa, the center of the country's impoverished coffee growing region. The clinic helps between 20 and 40 pregnant women every month. One 17-year-old woman, who subsists on the food her unemployed husband grows in their garden, grabbed Abraham's wrist and told her that Casa Materna was the nicest place she'd ever been. Unfortunately, it's having trouble meeting its $3,000 monthly budget. "It's in danger from the failure of some of this funding," she says.

More help is one the way. At the press conference, the United Nations Foundation announced it would donate $250,000 to 34 Million Friends, putting it a quarter of the way toward its second million. And next week, Roberts and Abraham are traveling to Brussels to launch a European version of the campaign. "Eventually we want to find millions of people worldwide who would chip in small amounts every year to show their commitment," Roberts says.

Roberts' commitment has been strengthened by her travels and by the outpouring of support that comes in the mail every day. "This is the one thing I want to spend my retirement on," she says.

Shares