The Pentagon hawks who planned for postwar Iraq assumed American troops would be welcomed with flowers and gratitude. They assumed Saddam's regime could be decapitated but the body of the state left intact, to be administered by American advisors and handpicked Iraqis. They assumed that other countries, despite their opposition to the war, would come around once they saw how right America was, and would assist in Iraq's reconstruction.

The war's architects placed such unyielding faith in their assumptions that when they all turned out to be wrong, there was no Plan B.

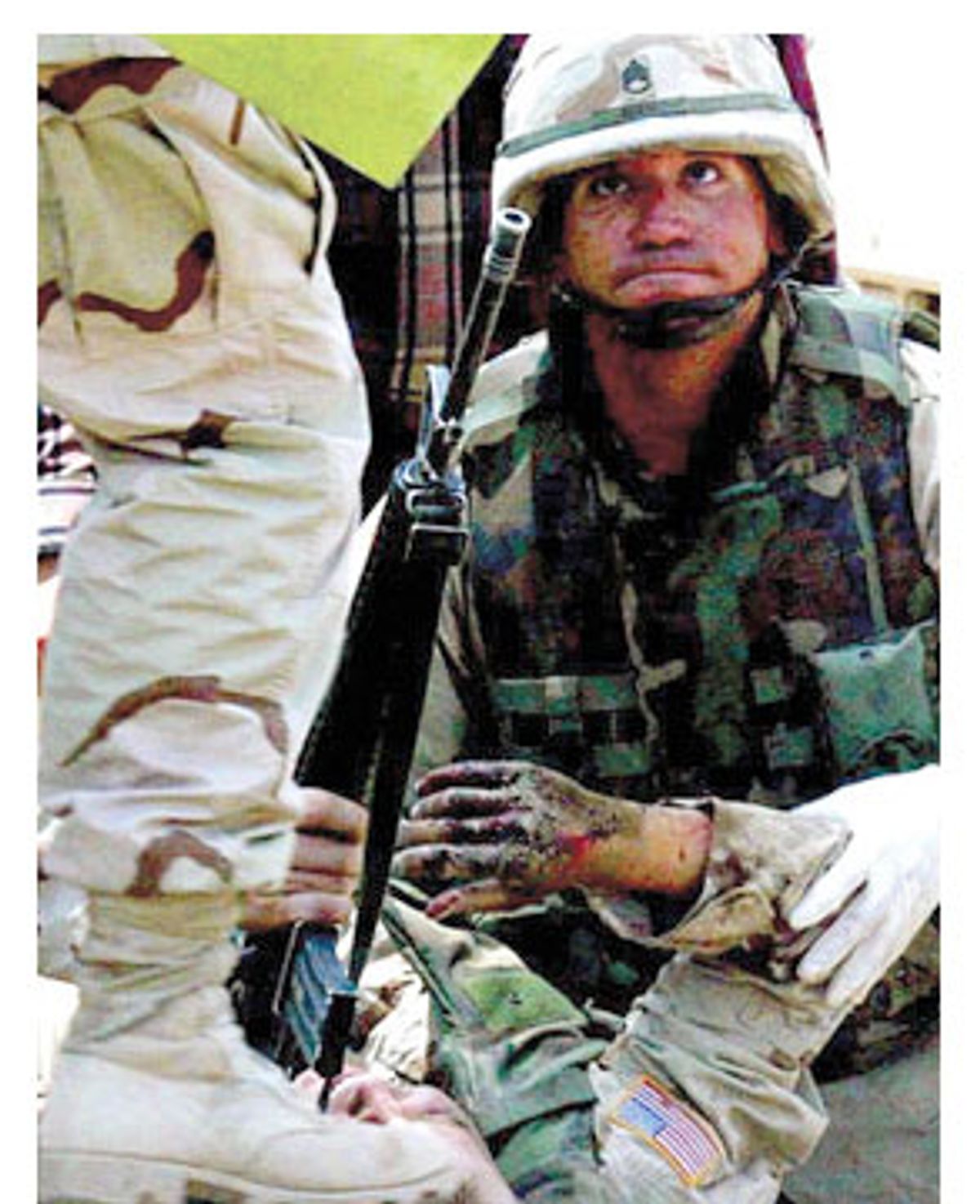

Now, demoralized American forces are being attacked more than a dozen times a day and nearly every day an American soldier is killed. Iraqis are terrorized by violent crime; they lack water, electricity and jobs. With gunfire echoing through the night and no fans to stir the desert heat, people can't sleep and nerves are brittle. The number of troops on the ground is proving inadequate to restore order, but reinforcements, much less replacements, aren't readily available, and foreign help is not forthcoming. Saddam Hussein, like Osama bin Laden, is still at large. The White House now says the occupation will cost nearly $4 billion a month. While American fortunes could always improve, on Wednesday, Gen. John P. Abizaid, the new commander in Iraq, said American troops are fighting a guerrilla war, contradicting the sanguine rhetoric coming from the administration.

America isn't losing the peace. The peace never began.

The current chaos in Iraq, many experts say, is the inevitable result of grandiose neoconservative ideology smacking into reality. The neocons underestimated the Iraqis' nationalism and their mistrust of America. They were so convinced that a bright new Middle Eastern future would inevitably spring from military victory that they failed to prepare for any other scenario. "Everything derives from a very defective understanding of what Iraq was like," says retired Col. Pat Lang, who served as the Pentagon's chief of Middle Eastern intelligence from 1985 until 1992 and who has closely followed the discussions over the Iraq war and its aftermath. "It was a massive illusion that the neocons had. It all flows from that."

Much has been made recently of exaggerations and misinformation used in building the case for war. It now seems that the postwar plan was predicated on similar misinformation, if not outright self-delusion. "They knew what Iraq was like and nobody could argue with them about it, including the people in the intelligence agencies," says Lang. Just as administration hawks took over intelligence gathering during the prelude to war by creating the Office of Special Plans in the Pentagon, they also dominated the postwar planning, refusing to let any evidence enter the discussion that contradicted their ideology.

That's why "there doesn't appear to have been" a contingency plan, according to Stephen Walt, a professor of international affairs at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government. "It's scary but true. An underlying assumption of this whole campaign against Iraq and the larger campaign to remake the whole Middle East was that all we had to do is knock off Saddam Hussein and everything else would fall down obediently at our feet. The Iraqis themselves would welcome being liberated, the Syrians and Iranians would be cowed and start doing what we want, Israel would be able to impose a peace on the Palestinians because they'd be intimidated, and all will be for the best in this best of all possible worlds."

Official policy was to treat this scenario as inevitable. Lang says the war's architects "simply didn't allow" anyone to plan for an outcome that didn't match the one they envisioned. "If you think back, the word was you didn't have to worry about this, there wasn't going to be any occupation," he says. According to Pentagon hawks, he says, "this wasn't an occupation, it was a liberation. The Iraqi people would simply take charge of their own affairs and we could go home almost immediately. They didn't think [retired Lt. Gen. Jay] Garner's people were going to be in Iraq for more than three months. That's why there are so few troops in the plan. The assumption was that all you had to do was defeat the Iraqi military, liberate it from Saddam Hussein's henchmen and these people would immediately take charge of their own affairs. There was great disdain for those who thought otherwise."

In fact, those who thought otherwise were cut out of the process altogether. Humanitarian NGOs that would be doing postwar work in Iraq were kept in the dark, says Kevin Henry, advocacy director for CARE, and the groups within the government that they usually work with were marginalized.

"One of the really amazing things for us," Henry explained, "and this does account for some of the failures in planning, is that the interagency process within the U.S. government for planning for the humanitarian response and reconstruction was being co-chaired by the [White House's] Office of Management and Budget and the National Security Council. These are not the agencies of the U.S. government that have the greatest experience in relief and reconstruction. The State Department, U.S. AID, the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance -- they're the organizations that we and all the other humanitarian organizations have a history of working with."

On July 12, Knight Ridder newspapers reported that the Pentagon ignored the State Department's eight-month-long "Future of Iraq" project, which involved Iraqi exiles and government agencies preparing strategies "for everything from drawing up a new Iraqi judicial code to restoring the unique ecosystem of Iraq's southern marshes, which Saddam's regime had drained. Virtually none of the 'Future of Iraq' project's work was used once Saddam fell."

"Those with greatest expertise were not completely sidelined, but they certainly weren't at the center of the planning process," says Henry, who prepared testimony about planning failures that CARE is delivering to a congressional committee on Friday. "Every time we would ask for more information, essentially we'd be told, 'Trust us, don't worry, we know what to do.'"

The administration continues to stand by its war plan. In a speech to the Center for Strategic and International Studies on July 7, Douglas Feith, undersecretary of defense for policy, correctly noted that none of Iraq's worst-case scenarios have materialized.

"Had we decided that large numbers of forces -- large enough to police the cities to prevent the immediate post-regime-collapse looting -- were the top priority, we could have delayed the start of the military action and lost tactical surprise, but then we might have had the other terrible problems that we anticipated," Feith said. "War, like life in general, always involves tradeoffs. It is not right to assume that any current problems in Iraq can be attributed to poor planning."

Other officials, though, say that planning wasn't just poor -- it was virtually nonexistent. "In the aftermath of a quick war, we find ourselves in the deplorable situation of having no planning, no allies, and no burden-sharing," says U.S. Rep. Ellen Tauscher, D-Calif., a member of the House Armed Services Committee.

And burden-sharing is crucial, because right now, there aren't enough troops in Iraq to keep order. Many commercial buildings in Baghdad are protected by U.S. forces, says David Andrus, director of the Peace and Conflict Studies Program at the University of Southern California School of International Relations, who recently returned from Iraq. But with only 147,000 American soldiers on the ground, there isn't enough manpower to guard schools, hospitals, utilities and neighborhoods.

"The security situation in Iraq is getting worse, not better," CARE reported on July 8. "It is the biggest impediment to delivering effective humanitarian aid. Murders and carjackings are common. The frenzy of looting that followed the war is over, but theft is still a serious problem for aid agencies." As the New York Times reported on Wednesday, rape is also increasing.

Lack of security, which is most acute in the Sunni triangle around Baghdad, hinders efforts to repair Iraq's infrastructure. A month ago, the electricity situation was improving -- every day, it seemed, there was power for a few more hours. Since then, though, electrical components have been looted and Iraqis working to restore electricity have been attacked, reversing gains. "Water, waste treatment, hospitals and factories in Iraq all depend on electricity," says CARE. "The risk of a health crisis grows as clean drinking water remains scarce, temperatures routinely exceed 40 degrees [Celsius, 104 Farenheit] and hospitals and healthcare centers struggle to provide treatment to sick people."

Administration officials recently have blamed the lack of electricity and water on Saddam's failure to upgrade infrastructure over the years. According to Gen. Carl Strock, deputy director of operations for the Coalition Provisional Authority, the electrical system is antiquated.

"It's basically 1960s technology," he said in a July 9 press briefing in Baghdad. "Due to its age and condition, they can only generate about 4,500 megawatts [per day]. The national demand right now is about 6,000 megawatts." The water supply situation is similar, as the pumps rely on the electrical system. "Here in Baghdad, before the war we were getting about 2,000 million liters per day of drinking water," Strock said. "Right now we're about 1,400, and we should be back to 2,000 in the next three months or so."

For Baghdadis, access to electricity largely depends on where they live. In the richer neighborhoods, most households have generators -- so even if the power goes down, they can still sit in air-conditioned rooms on 110-degree days. As has always been the case, the people most affected by the lack of electricity in the heat are the poor. But for them, the lack of electricity and adequate water supply is nothing new -- they didn't have them before the war either. "There's never been enough electricity to go around," says Strock. "Saddam definitely used the provision of utilities as a political tool to reward those he wanted to reward and punish those he wanted to punish."

For the people living in the areas surrounding Basra, this means that nothing has really changed. In the cities of the south about 60 percent of the people in the urban population have access to drinking water -- in rural areas the figure is closer to 30 percent. This is approximately what they had before the war, and levels are expected to rise.

But according to Johanna Bjorken of Human Rights Watch, who returned to the U.S. from Baghdad on July 1, the electricity situation in the Iraqi capital actually got worse in June. "When the month of June started," Bjorken told Salon, "electricity levels were at roughly half of what they were before the war. By the end, there were entire days where Baghdad was completely without power."

There's no doubt that many Iraqis welcomed regime change, and there's still a reservoir of goodwill toward U.S. forces. Though some Iraqis working with American troops have been assassinated, many continue to risk their lives to cooperate with the occupation, eager for the opportunity to rebuild their country. In Baghdad and the Sunni areas of central Iraq, though, patience is evaporating amid a growing sense that life has gotten even worse since the Americans arrived. On the streets of Baghdad, there's a mounting conviction that the U.S. invaded to plunder Iraq's resources rather than to free its people. "We have moved from victorious liberator to hated occupier very quickly," says Tauscher.

Nor is the insecurity limited to central Iraq. Though there's far less resistance in Shiite southern Iraq, "the climate of fear and insecurity is overwhelming in Basra," Amnesty International reported on July 4. "The widespread looting and scavenging of public buildings, witnessed in the first days of occupation, has decreased, but crime, often involving violence, remains much higher than before the occupation ... The U.S. and U.K., as occupying powers in Iraq under international law, have a clear responsibility to maintain law and order, and to protect the Iraqi population. The occupying powers have clearly failed to live up to this obligation. They have shown a lack of preparedness -- in terms of political will, planning and deployment of resources -- to bring the lawlessness under control, and millions of Iraqi men, women and children are paying a terrible price."

It didn't have to be this way. In February, when Army Chief of Staff Eric K. Shinseki (since retired) told the Senate that several hundred thousand soldiers were needed to subdue Iraq, he was derided by hawks at the Pentagon. Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz called his estimate "wildly off the mark" and said, "I am reasonably certain that they will greet us as liberators, and that will help us to keep requirements down."

Now, though, many experts say that the worst of the chaos in Iraq could have been contained if there had been enough troops on the ground from the beginning. There's a growing consensus that something close to what Shinseki suggested might be necessary to turn the situation around.

"Certainly the short-term problems that we faced could have been prevented if there had been proper planning and a very careful assessment of what the postwar situation was likely to look like," says professor Walt at Harvard. "If we had gone in with a much larger force, the way former Chief of Staff Shinseki wanted, and a very generous aid package that was ready to roll at the moment of victory, you probably could have put off a sort of day of reckoning. Whether that would have ultimately prevented problems from emerging down the road, we don't know."

War planners apparently believed that, since their precision bombs would largely spare the Iraqi state's infrastructure, the country could operate more or less normally as authority was transferred from Saddam's regime to someone like Ahmed Chalabi, leader of the Iraqi National Congress. Though some in the administration grew disenchanted with Chalabi, Wolfowitz and his coterie never stopped pushing him.

"One of the assumptions was that they could knock off the very top of the Baath party but leave the rest of the regime intact," says Walt. "They were going to install Ahmed Chalabi on top of the regime, but the rest of the state would still be functioning. What happened instead was they knocked off the top and the rest of the state disintegrated."

As soon as Baghdad fell, government ministries and public utilities were stripped by looters. "It's ironic that the hospitals and water treatment plants and electrical infrastructure was virtually spared from the bombing," says Henry, "and then completely devastated by the looting that followed."

Some of this could have been foreseen. "When Hurricane Andrew struck the Florida coast in 1992, it destroyed an airbase, destroyed towns, and Florida went into anarchy," says professor Andrus of the University of Southern California. "People were hiding in their houses with guns to protect themselves from roving bands of thieves and rapists. It was a horrible place. Now if you take Iraq, that's been under this very tight dictatorship for decades, and all of a sudden the U.S. comes in and sweeps aside this very tightly controlled political and civil structure, you have a huge vacuum and the people aren't prepared to deal with it, so it deteriorates very quickly."

Lacking the manpower to stop the deterioration, troops simply stood by as the foundations of civil society burned. "If we had had 250,000 troops, the targets of looting might have been secured," says ex-Marine Lou Cantori, an expert in military policies in the Middle East at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, who has taught at West Point, the U.S. Air Force Academy and the U.S. Marine Corps University. "We were shorthanded because of the Rumsfeld team's preconceptions, and therefore the troops stood around and watched as the infrastructure of Iraq was destroyed.

"Americans cannot enforce order in the society," Cantori continues, "and because order cannot be enforced, reconstruction cannot take place, and because there's no order and no reconstruction, there cannot be an American withdrawal. This is a quagmire and a situation that is deteriorating, and it's about time that somebody started saying this."

Meanwhile, Iraqis, having seen the American military crush Saddam, the most powerful force in their universe for decades, can't believe that these same soldiers are incapable of getting the lights to work, and many believe the hardships they're suffering stem from American indifference. Their hostility makes the situation even more volatile for the Americans, who anticipated a grateful populace that would shower then with rose petals.

Many experts predicted such Iraqi animosity, but the war planners dismissed their warnings. "I know from lots of discussion and debates with these guys that they believe so deeply in the power of the democratic idea, and in people's view of the United States as benign, that they just assumed that we would be seen as liberators," says Bruce Jentleson, a former senior foreign policy advisor to Vice President Al Gore and author of 1994's "With Friends Like These: Reagan, Bush and Saddam, 1982-90."

Thus none of the troops sent into Iraq were prepared to be occupiers. The strain of doing a job they're not trained for while under siege from people they expected to welcome them is increasingly obvious. Every day brings new reports of the rage and misery of soldiers in the 3rd Infantry Division, some of whom have been in the region for 10 months, their homecoming repeatedly promised and repeatedly postponed.

"If Donald Rumsfeld was here. I'd ask him for his resignation," Spc. Clinton Deitz of the 3rd Infantry Division told ABC News on Wednesday. A 3rd I.D. officer told the Christian Science Monitor that the troops "vent to anyone who will listen. They write letters, they cry, they yell. Many of them walk around looking visibly tired and depressed ... . We feel like pawns in a game that we have no voice." The hawkish Weekly Standard reports in a cover story this week that "the soldier story now is that the 3rd Infantry is 'black' -- meaning critically short -- on Prozac supplies."

The intensity of the 3rd I.D.'s outspoken criticism of its leaders is unprecedented, says Lang. "You're getting professional, noncommissioned officers in the U.S. Army complaining to media people about the leadership," he says. "I can't remember an instance when a sergeant first class with 20 years of service says the same kind of stuff" he's hearing from such soldiers in Iraq. After all, such complaints are actually illegal under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which, says Lang, "forbids active-duty military personnel from publicly holding up to ridicule people in the chain of command above them."

That they're doing it anyway indicates the depth of their unhappiness, and "they get meaner and tougher when they're unhappy," Lang says. "If they get really even more unhappy, you're going to start having incidents involving them and Iraqi civilians." There have already been a few. In April, U.S. soldiers opened fire on Iraqi demonstrators in Falluja, killing 13 and wounding dozens more. In June, the Associated Press reported that soldiers were accused of killing five Iraqi civilians whom they mistook for attackers. This does little to convince the locals of American benevolence.

It's a dangerous spiral, Walt says. "We are being forced to take much more aggressive action against potential resistance. The more you go out and have to search people and search their homes and their mosques, the more angry they get. There's a lot more friction between American forces and the society than we'd like."

Cantori says the only way the situation can be stabilized now is by raising troop levels to those suggested by Shinseki, but doing so would be politically disastrous for Bush. "American public opinion is that troops should be coming home," he says. "If they send two divisions of troops right now, it's an indication that their policy has failed."

Besides, there simply aren't enough soldiers available. Lang points out that forces were scaled back during the Clinton administration, and that there are only three divisions available to be rotated into Iraq, two in the Army and one in the Marines. "We are stretched way too thin," says Tauscher.

Unfortunately for the administration, other countries aren't rushing to send their own contingents. According to a July 17 Wall Street Journal article, "even allies who supported the war have failed to follow through with major commitments. Hungary pledged a truck company for Iraq. But defense officials later learned the Hungarians were willing to send 133 drivers, but no trucks or mechanics." This week India refused to send 17,000 of its troops to Iraq without a U.N. mandate, despite American pressure and India's eagerness to improve its relationship with Washington. Even Britain has reduced its contribution, from 45,000 troops during the war to 15,000 now.

This may force the Pentagon to call up 10,000 National Guard soldiers, the Wall Street Journal reported Thursday. Yet even that won't bring troop strength up the level many say is necessary to stabilize Iraq.

"India is very telling," says Jentleson. "There's a lot of discussion about a strategic partnership between the U.S. and India," he says, and for many Indian officials, helping the U.S. in Iraq makes sense as a way of gaining U.S. support against Pakistan. The Indian population, though, is viscerally opposed to "supporting American unilateralism, so even with expert foreign policy opinion behind it, they have to abandon it," he says.

"It's just like what happened in Turkey before the war," Jentleson continues. "The government said, 'Let's make a deal, because we're going to get a fair amount of money and U.S. support,' and their own parliament said no. The administration is really underestimating how pervasive is this concern about American unilateralism."

Many say the neocons have been blinkered by an essential inability to grasp others' opposition to their designs. "One of the things that seems to be a thread that runs throughout all of their thinking is a sort of big-stick view of the world, that the world tends to jump on the bandwagon and follow whoever the big dog is, that you can cow people and intimidate them and get lots of respect, that power generates its own respect," says Walt.

In this case, though, America's assertion of power has generated primarily resentment and Schadenfreude. "The Indian decision is not so much a serious blow in and of itself, but it's an indicator of world opinion that, having gone to war in defiance of the wishes of most of the international community, the rest of the world is not going to be in a hurry to bail America's chestnuts out of this fire," Walt says. "In fact, some countries are likely to be eager to let us stew in these juices for quite some time."

The situation can still be salvaged, but many say that to do so, the administration will have to let go of the bombastic unilateralism that brought it to war in the first place. They say Iraq can only be saved by appealing to the United Nations and giving up the dream that Americans can fashion the country into a beacon of pro-Western democracy in the Middle East that would undermine regimes like Syria's and Iran's. "That was always a goofy dream," says Walt.

"You have to be willing to accept the fact that the United States is not going to run Iraq," says Col. Lang. "You have to transfer control to the U.N. so countries like India and France will contribute troops. Until you give up the idea that this was our victory and this is our occupied territory, the situation is not going to be stabilized."

Resistance from hardcore Baathists will likely continue regardless, but Jentleson says U.N. oversight would defuse some of the anti-American anger among ordinary Iraqis. "If there is a sense that the international community were the ones providing the authority for remaking Iraq, it would be very different than going out and shooting an American," he says. "If the U.N. was genuinely behind this, it would give it authority. There's a difference between power and authority. Right now we're relying totally on power, and that's not sufficient."

Furthermore, Jentleson says, if Iraq's reconstruction were placed under the aegis of the U.N., trained peacekeepers and civil administrators from around the world would likely flow in. "It would be brilliant diplomacy to now engage the U.N. and engage other countries," he says.

To do this, though, would require a profound attitudinal shift in an administration that has clung stubbornly to its own assertions, whether or not the facts cooperate. "We may have to sit down and have a meal of humble pie, followed by a little crow, in order to deal with the loss of credibility that we have worldwide," says Rep. Tauscher.

"What other reason do they have for not [going to the U.N.] other than that they have decided it's their way or the highway?" she asks. "I can't tell you why they're not doing it. They don't even tell us why they're not doing it. We asked Secretary Rumsfeld, 'Well, have you talked to the French?' He says, 'I don't know.' Who else would do the military-to-military discussion but him? There are 2 million troops in NATO countries that we have refused to ask for help."

Right now, there's not much sign that the administration is ready to rethink its control of the occupation. On NBC's "Meet the Press" last Sunday, Rumsfeld continued to insist that the force in Iraq is already multilateral. Asked by Tim Russert whether he'd be interested in having the U.N. take over, he responded: "I don't know what it means by 'take over.' At some point I think -- they already are playing an important role, and they have to play an important role. And we have got a large coalition of countries there."

Rumsfeld also insisted that the United States is making progress in Iraq, and that the recent attacks are just the last gasp of a dying regime. "The more progress we make I am afraid the more vicious these attacks will become, until the remnants of that regime have been stamped out," he said.

Yet Walt thinks that behind the scenes, the neocons are scrambling. "I believe that they've been shocked by what's happened," he says. "The architects of this war did not want American troops to be there in large numbers for very long, for two reasons. First, they understand that if you had to occupy the country for a long period of time, you were going to look like an imperialist power, and that was going to cause a lot of trouble."

Secondly, he says, "if you have to tie up a lot of your forces in Iraq for a long period of time, you can't go off and threaten others. The whole idea was we were going to teach the Iraqis a lesson and that lesson was also going to be learned by the North Koreans and the Syrians. It's much tougher to threaten North Korea when much of your army is sitting in Iraq."

"Even given their own objectives," he says, "they blew this one big-time."

Salon assistant news editor Laura McClure contributed to this report.

Shares