Liberals who supported the war with Iraq had the unpleasant experience of aligning with people they despise and against those they respect, or at least respected. Many scorned the Bush administration and its putative motives, objected to the doctrine of preemption on which the war was based, and were dismayed by the way the president alienated America's allies. They recoiled at the hypocritical audacity of people like Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who spoke of Saddam's slaughter of the Kurds as a causus belli, even though, as part of the Reagan administration, he supported the Iraqi leader when the genocide was actually taking place.

But they went out on a limb and backed the war anyway, pushing aside their ingrained suspicion of American military might. Unlike much of the Democratic leadership, which supported the war for reasons of domestic politics, these liberals came to their position through conviction. Some decided that, after years of decrying Saddam's sadism, they wanted no part of a movement to prevent his ouster, no matter how cynical the administration doing the ousting. They didn't believe that the administration cared for the Iraqi people or their liberation, but they did believe that liberation would be, if nothing else, a side effect of the campaign.

Others, like Paul Berman, author of "Terror and Liberalism," believed in the idea of a remade Middle East. A few, including David Remnick, editor in chief of the New Yorker, Mitchell Cohen, co-editor of the left-liberal journal Dissent, and several staff members at the New Republic, agreed with former CIA analyst Kenneth Pollack's assessment that Iraq's weapons programs posed a threat that had to be dealt with eventually.

Yet now, as the systematic violence of fascism is replaced by the random violence of anarchy, Iraqis are daily telling journalists they were better off before. No weapons have turned up, casting doubt on the notion that Saddam was a real threat to anyone but his own brutalized people. America's recent plea for U.N. help is widely seen as proof that the administration of President George W. Bush, no matter how optimistic in public, believes the occupation is going poorly. Opponents of the war are saying, "I told you so."

Few liberal hawks, though, are making mea culpas, even if some of them seem increasingly uneasy. Most say that even if the postwar situation is a mess -- and not everyone agrees that it is -- the war was worth it. They say that the majority of Iraqis will have better lives because Saddam has been deposed, the regime's long-term threat to the world has been neutralized, and U.N. resolutions flouted by Iraq were enforced, even if America spurned the U.N. to enforce them. Most pro-war liberals find much to criticize in the postwar planning, but they say talk of failure and quagmire is as premature as Bush donning a flight suit to celebrate victory. Some may be having second thoughts, but they're keeping quiet.

"I still stand by the position I took, in fact very much so," says Dissent co-editor Mitchell Cohen, a professor of political science at Baruch College. "The argument that I made was partly made on humanitarian concerns, because I think the Iraqi regime under Saddam Hussein was indeed one of the most appalling regimes of recent memory. But my argument wasn't entirely made on the basis of that. The argument I made was that given the nature of the Iraqi regime under Saddam Hussein, this was going to have to be confronted sooner or later. In any event, I do think that however difficult and problematic the situation is now -- and I'm not very happy about a lot of things that have happened and mystified by a few of them -- I still think that in the long term the Iraqi people and indeed the world are safer because Saddam is gone from power."

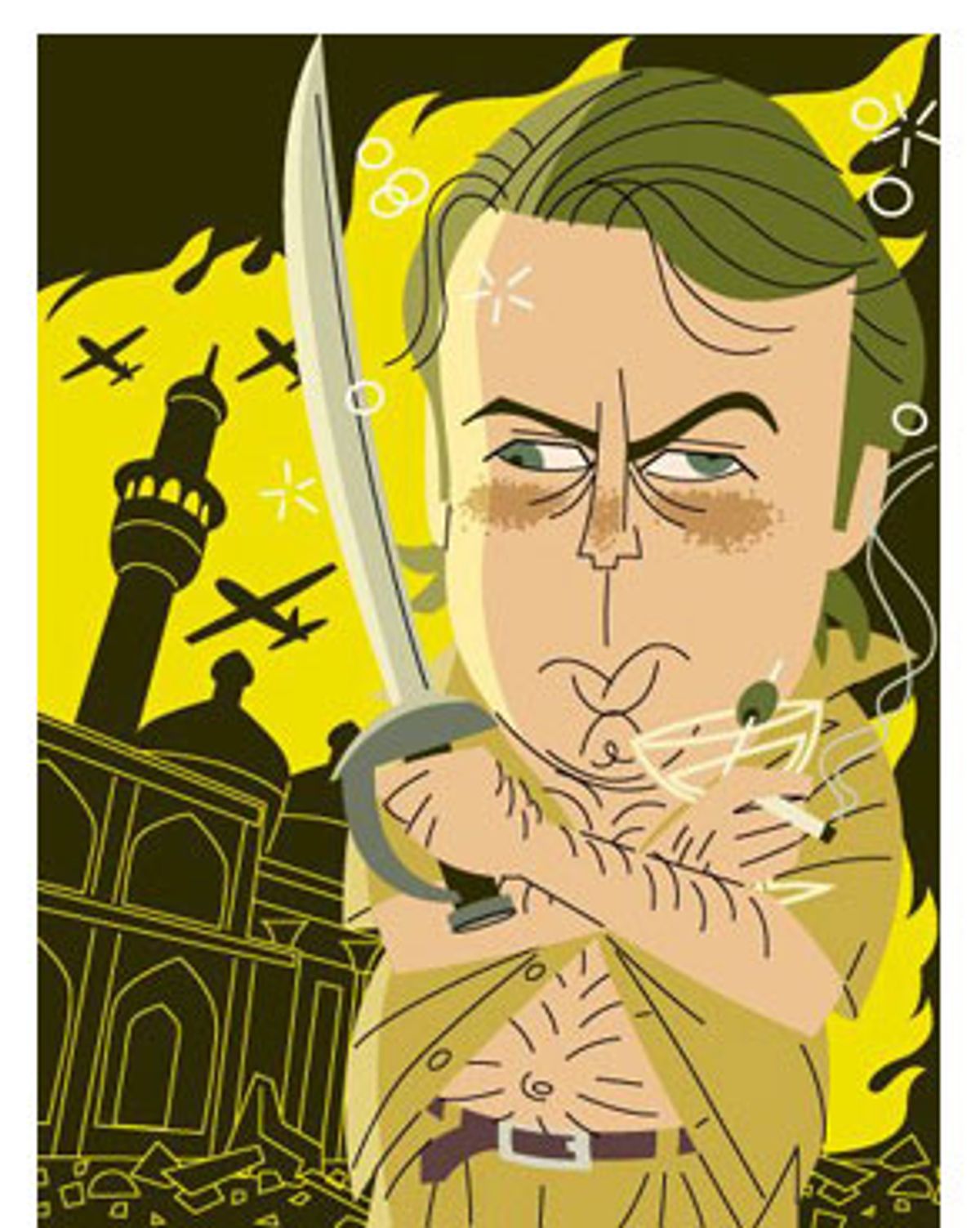

Christopher Hitchens, an ex-Trotskyite who famously broke with the left during the run-up to war, is even more sanguine about his stance. While the liberal conventional wisdom is that the occupation is a debacle, "I know from my own experience it's not true," he says. Hitchens recently returned from Iraq, where he hung out with L. Paul Bremer, the occupation's chief administrator, and his most recent Vanity Fair column paints a fairly rosy picture of the occupation's progress. "I was quite startled by how well it was going," he says. "I support it whether it goes well or not. I don't demand success in advance of a policy I support. It can take a long time if you want a revolution."

Hitchens admits being somewhat baffled by the American failure to get the electrical grid up and running in Iraq. "I must say it is staggering to me that this country can't mobilize the can-do bit, the know-how bit it's so famous for. That is amazing."

Still, while humanitarian concerns formed part of Hitchens' rationale, he says he doesn't much care if some Iraqis now say their lives are worse than they were under Saddam. "I've never yet been to any country that's undergone a revolution -- and by the way, if this was being called a revolution rather than an occupation, the left would be making excuses for it -- in any country that's undergone a revolution it's very common to find a perverse nostalgia for the old days. You still find it in Spain. The vast majority of Iraqis wanted [Saddam] to be removed even at the cost of foreign intervention, and still do. Most Iraqis and Kurds regard it as a deliverance. But suppose they didn't. The news has to be broken to them one way or another. Unfortunately, the government in their state wasn't one to which one could be indifferent. Iraq is not unfortunately just their internal affair."

Indeed Hitchens, perhaps more than any other commentator outside the febrile precincts of the right, believes in the connection between Saddam's regime and global Islamist terror. Iraq, he says, "was a launching pad for terrorist attacks." He bases that conclusion on Iraq's sponsorship of Palestinian terror and on suspicion that Saddam supported Ansar al-Islam, the Islamist movement that operated in the Kurdish no-fly zone. It's unlikely, he says, that Ansar al-Islam is an organic movement, because it doesn't make sense "that returning Afghan fighters decided to move to Kurdistan and attack the government there as their main jihad." Then he adds, "I myself interviewed [Palestinian terrorist] Abu Nidal [in Iraq] when he was most wanted man in the world."

Of course, while Saddam's support for Palestinian terrorists is well known, his connection to al-Qaida remains speculative, and most war opponents dismiss it outright. Similarly, the military's failure to find WMD -- and postwar revelations about exaggerated intelligence -- have led liberal opinion to solidify around the idea that Iraq was never a threat. Yet even as pro-war conservatives have turned to humanitarian arguments to justify the war retroactively, pro-war liberals continue to emphasize national security concerns.

It's ideologically convenient for war opponents to assume that the American failure to find chemical and biological weapons means Saddam didn't have them. But war supporters who've followed the regime for years say such a dismissal of Iraq's threat is far too glib. They admit to being baffled by the weapons' disappearance, but argue that the sacrifices Saddam made over the years to conceal them testify to their existence. After all, had Saddam complied with weapons inspectors, sanctions would have been lifted and he could have continued ruling Iraq without outside interference. He even could have restarted his weapons program once the world's attention was turned elsewhere.

"I'm as mystified as anyone about the weapons," says Cohen. "I fully expected that two weeks after the war began, all sorts of things were going to be found." Yet that doesn't mean he's changed his assessment of the danger Saddam posed. "I think the issue of weapons is far from over. I think we should be worried not just by the fact that they didn't find any weapons, but by the fact that they found nothing. Something doesn't seem right about this to me. It doesn't seem to me plausible that Saddam was willing to give up $150 billion in oil revenue" -- not to mention his own rule in Iraq - "to hide an arsenal that doesn't exist."

At the New Republic, a leading voice of the liberal hawks, senior editor Jonathan Chait seems slightly more uncertain about Saddam's weapons, but also stands by his support for the war and his assessment that Iraq, if not a threat already, would have metastasized into one. "I still think it was a good idea, although I'm less certain about that than I was before," he says. "The reason I'm less certain is that the threat is far less immediate than we thought it was at the time. It was very hard to predict it would have turned out this way. There's a fairly long history of outside intelligence services underestimating weapons systems in Iraq. To me, the threat was always that he would obtain nuclear weapons. You couldn't be sure, but you had these external intelligence agencies saying one to three years, maybe a little more. Now it seems pretty clear there was no active nuclear program in Iraq."

Yet Chait says that doesn't wholly undermine the rationale for war. "There were still nuclear scientists in Iraq, and I still think eventually, left to his own devices, Saddam Hussein would have obtained some kind of nuclear weapon. I don't want to give the impression I'm clinging to this possibility to justify my argument. I'm just not sure we can close the book on the status of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq right now."

Coupled with Saddam's potential destructiveness, Chait says, was Iraq's history of spurning more than a decade's worth of U.N. resolutions regarding weapons inspections. "It all ties together in a way that's hard to explain in a simple or clear sentence. I don't think the United States or the United States acting through the United Nations can say, 'Here are our conditions for ending the [Gulf] war' and then have the country flout those requirements and then do nothing. It's deadly for your credibility. It invites hostile behavior from rogue states in the future."

Chait, like Cohen, says he never had high hopes for democracy in Iraq, so the current chaos doesn't shock him much. The humanitarian case for war, he says, never convinced him. "I was never confident that there would be democracy in Iraq," he says. "I hoped there would be. I always argued that there would be a decent chance that the government that ended up in Iraq would be only marginally better than Saddam. I don't think you can launch an entire war just to get a marginal improvement of the living conditions of a country."

Indeed, it's those who were most concerned about humanitarian issues -- who supported the war precisely because it would bring the Iraqis some marginal improvement in living conditions -- who seem most disillusioned by the current situation.

At least, those who are speaking out do. Others have grown strangely silent as a messy occupation and restive population challenge their optimistic pre-war theories.

Kanan Makiya is a Brandeis professor and Iraqi exile who was the foremost documenter of Saddam's human rights abuses. Before the war, he issued passionate exhortations to his Western comrades to show solidarity with oppressed Iraqis, even if it meant swallowing their own partisanship to back Bush's policy. Yet Makiya always opposed a protracted American military occupation. In February, he began to realize that the administration didn't share his agenda for rebuilding Iraq, and he published a blistering Op-Ed in the Observer.

Describing a plan much like the one that was later implemented, he wrote: "The United States is on the verge of committing itself to a post-Saddam plan for a military government in Baghdad with Americans appointed to head Iraqi ministries, and American soldiers to patrol the streets of Iraqi cities. The plan, as dictated to the Iraqi opposition in Ankara last week by a United States-led delegation, further envisages the appointment by the U.S. of an unknown number of Iraqi quislings palatable to the Arab countries of the Gulf and Saudi Arabia as a council of advisers to this military government."

This plan, he wrote, "is guaranteed to turn [the Iraqi] opposition from the close ally it has always been during the 1990s into an opponent of the United States on the streets of Baghdad the day after liberation ... We Iraqis hoped and said to our Arab and Middle Eastern brethren, over and over again, that American mistakes of the past did not have to be repeated in the future. Were we wrong?"

Makiya hasn't yet to come forward to answer his own question. He hasn't published anything in months, and didn't respond to requests for an interview.

"I'm embarrassed for people like Kanan," says Jim Prince, president of the Democracy Council, an NGO that promotes democracy in developing countries. "Kanan is one of the world's biggest hearts. He, as a liberal Shia, really advocated for the United States and supported the United States. I haven't spoken to him recently, but he has to be so disillusioned with America."

If so, he's not the only one. Prince, a human rights activist who once worked in Iraqi Kurdistan and attended the founding meeting of the Iraqi National Congress, is unique among liberal hawks in that he's now recanting, or at least rethinking, much of his previous position. He returned from Northern Iraq three weeks ago, and says: "I never imagined that it would be such a screwed-up situation.

"Most of us supported the war because we felt from a moral, human rights angle that it would improve the lives of the Iraqis," he says. "We find out later that the planning for such [humanitarian] activities were pushed aside. The lack of planning shows the lack of importance [the administration] placed on these issues."

Of course, many say that it's still likely that regime change will benefit Iraq's people in the long term, but Prince shares some of the doubts voiced by the Iraqis themselves. "The only argument you can make now [to Iraqis] is, 'You're not better off today, you're not better off next week, but in the long run you and your family will be better off.' It's hard for Iraqis to understand that. It's really hard to make that argument with a straight face when you're talking to someone who may have supported the war aim but who cannot feed their family or who just had to pay ransom to get their kid back or was mistakenly taken away by the Americans because they had a relative in the Ba'ath party."

"A lot of people in the human rights community, they are so jaded now, so disappointed," he says, adding that they feel "betrayed" by an administration that co-opted their rhetoric but ignored their concerns.

Besides disenchantment, there's a degree of denial. David Phillips, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who before the war acted as an advisor to members of the Iraqi opposition, now says he was never pro-war. "I think that, if you look at everything that I've written and said, you'll never find an instance in which I said I supported the war," he says. "I supported better freedom for the Iraqi people and the opportunity for them to express their democratic desires."

Before the war, though, his arguments sounded distinctly hawkish. In February, he wrote a Wall Street Journal Op-Ed about a French and German proposal to deploy U.N. peacekeepers to back up weapons inspectors: "The lessons from Bosnia are clear. Adopting resolutions at the U.N. Security Council without the resolve to implement them is a formula for failure. Unless diplomacy is backed by force, tyrants will always prevail. Moreover, appeasement by European leaders did not work in Bosnia, and it will not work in Iraq ... Europe still has not learned its lesson. Neville Chamberlain's appeasement did not work against Hitler, and appeasement failed in Bosnia with Slobodan Milosevic. Appeasement will also fail in Iraq, with deadly consequences."

Now, Phillips seems bitterly disappointed by the consequences of invasion. "Bottom line here, there were a lot of elaborate plans made for the liberation of Iraq. When those plans were implemented, they fell far short of expectations," he says. "The reason those plans fell short is that the participation of Iraqis wasn't valued by the civilians in the Pentagon, who only wanted to work with Iraqis in the Iraqi National Congress and felt that they knew what was best. They threw out a year's worth of planning and proceeded with their own plans, their own people, their own timetable, the results of which have left a lot to be desired."

Thus, while Phillips speaks to many Iraqis who talk about the "intangible benefits" of the war, he says: "Until their lives are materially improved, there's going to be a lot of skepticism among Iraqis about whether or not this was a good idea."

This raises the question of whether liberal humanitarians were remiss in not foreseeing administration incompetence. Even if the war was worth fighting, was it wrong to trust the Bush White House and Rumsfeld Pentagon to get it right? Todd Gitlin, a Columbia professor, longtime activist and ambivalent opponent of the war, says yes. "If you propose a course of action which is plausibly at serious risk of being manhandled by the actually existing authorities who are going to implement your plan, even if you have differentiated your idea of proceeding from their idea of proceeding, I do think you bear some responsibility" for how things turn out, he says.

Phillips, though, says there was no way to foresee the way Bush would mishandle the occupation.

"Plans for Iraq were proceeding in a positive way up until the point where the president assigned postwar civilian administrative responsibility to the office of the secretary of defense," he says. "From that point forward, the participation of Iraqis and the contribution of other agencies in the U.S. were ignored or disparaged. Was it naive not to have expected that? I can't say. Up until the point where the presidential instruction was given, there was reasonable basis to expect something different than what we've seen. I certainly did."

As did others nationwide. "I know academics across the country who were for the war," Prince says. "A lot of them are embarrassed now."

That matters because the furious Iraq debate and its murky denouement could have consequences that are far more than academic. After all, one reason America failed to even try to stop the 1994 Rwandan genocide is because the country was chastened by the Somalia debacle the year before, just as the ghost of Vietnam kept the U.S. from intervening early enough in Bosnia.

The horror of Bosnia drove many liberals away from post-Vietnam isolationism. If the situation in Iraq doesn't improve soon, it could drive them back. "There's a danger that the transparent deceptions of the case that was made for the war will discredit other arguments on behalf of intervention, including arguments for multilateral interventions," says Gitlin. In other words, it might get a lot harder to be a liberal hawk, no matter how worthwhile the fight.

Shares