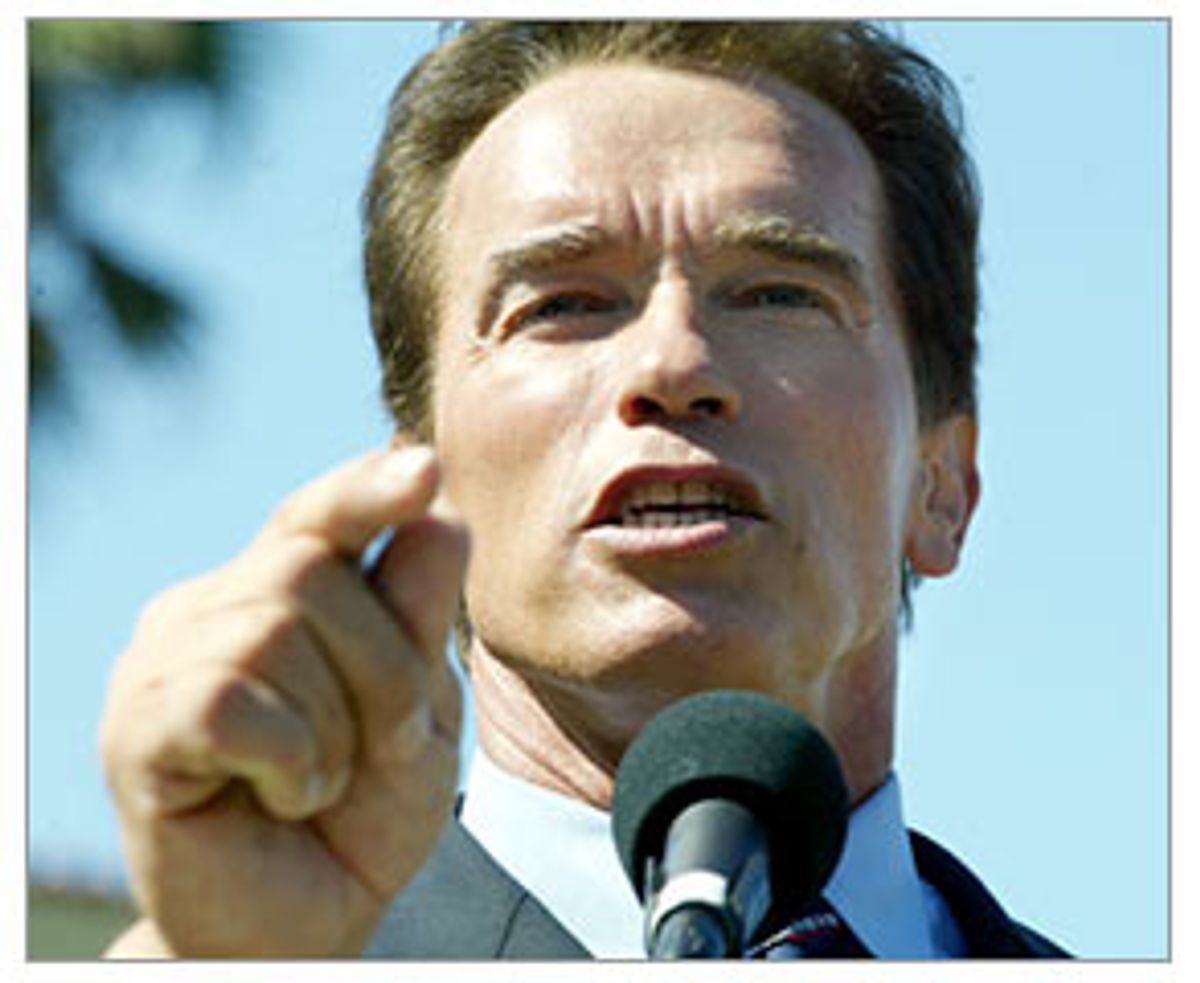

Of all the California gubernatorial candidates, only one has inspired a nickname for a Schedule 3 controlled substance. The candidate is Arnold Schwarzenegger, and the substance is anabolic steroids, or -- as some illicit users have dubbed them -- "Arnolds." It's only fitting that Schwarzenegger is immortalized in this way, since he epitomizes the promise of steroids: monstrously big muscles that can morph a scrawny nobody into a ripped he-man with health, wealth, popularity -- and maybe even a shot at running the most populous state in the country.

The past steroid use of the seven-time Mr. Olympia, five-time Mr. Universe, and one-time Mr. World is no secret. Schwarzenegger portrays his doping as a youthful indiscretion that, despite its career-enhancing effects, he would prefer to put behind him. Appearing on "Larry King Live" in August, he said that using steroids "was stupid, because it was in the late '60s, early '70s, when we didn't know any better." Campaign spokesperson Karen Hanretty explains that "Arnold has made it clear that if he knew then what he knows now, he wouldn't have taken steroids." (Not that he's always been remorseful: In 1996, he told the Los Angeles Times, "It was a risky thing to do, but I have no regrets. It was what I had to do to compete.")

For over a decade, Schwarzenegger has condemned all athletic and cosmetic steroid use. As the head of the President's Council on Physical Fitness under George Bush the elder, he urged kids to stay off steroids and instead rely on hard work to reach their athletic goals. "There are no shortcuts," he told USA Today in 1990. And according to Schwarzenegger's personal Web site, his Arnold Classic bodybuilding competition was the first of its kind to require drug testing.

His anti-steroid message is pretty standard "Just say no" stuff: Steroids are unsporting and, since 1990, illegal. But when it comes to talking about what steroids can do to you, Schwarzenegger steers clear of specifics. Talking with King, he explained, "In the late '70s and in the early '80s, research was done and you found out that it's actually damaging, that it causes side effects and it is bad for your health." He wasn't inclined to elaborate on how that might relate to him personally. In a 1988 Playboy interview, he insisted that steroids hadn't harmed him: "I don't worry about it, because I never took an overdosage. I took them under a doctor's supervision once a year, six or eight weeks before competition. I was always careful and checked, and I never had any side effects."

He repeated his claim of a clean bill of health a few years ago to the Los Angeles Times, referencing one rumored ill effect of heavy doping. "I have no health problems," he said. "No kidney damage or anything like that from using them."

Schwarzenegger has good reason to be cagey when talking about the long-term effects of anabolic steroids. More than a dozen years after Congress outlawed their nonmedical use and put them in the same category as amphetamines and barbiturates, the verdict on their ultimate health consequences is still out. Researchers and doctors say they have good reason to believe steroids can cause serious harm, but despite decades of dire warnings, they're still scrambling to find scientific proof. On the other hand, there's surely no solid evidence that pumping up with steroids is exactly good for you, either.

Anabolic steroids, more accurately known as anabolic-androgenic steroids, are synthetic versions of testosterone. Though they have legitimate medical uses, they are best known as a way to beef up in a hurry. In the 1930s, researchers discovered that when fed to animals and humans, these compounds made muscles bulge and fat melt away. Though rumor has it that German athletes took testosterone in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, the first documented use of performance-enhancing hormones by an athlete involved an aging racehorse named Holloway in 1941. By the time Schwarzenegger discovered steroids in the late 1960s, humans were in on the action, too. Competitive athletes from NFL linemen to East German swimmers regularly popped, injected and openly praised them. The editor of Track and Field News hailed steroids as the "breakfast of champions." Over the next three decades, their use spread from pro athletes to high school jocks, gym rats, and ordinary guys who just wanted to transform their paunches into six-packs.

From the start, it's been clear that synthetic sex hormones can come with a slew of undesirable side effects. Men who take them may lose hair, grow breasts, and develop acne. If that weren't enough, steroids can, as the hardcore bodybuilding mag Muscular Development puts it, "make your testes the size of peanuts."

Women who take steroids may grow unwanted hair and see their breasts shrink and clitorises grow to what one dismayed user once termed "embarrassing proportions." Steroids can also fuel aggression -- not necessarily an undesirable outcome for competitive athletes or Hulk wannabes. As Dr. Charles Yesalis, a professor of public health at Penn State and an expert on nonmedical steroid use, recalls, "An All-Pro NFL player said to me, 'If you're an asshole before you use steroids, you're a bigger asshole after you use them.'" In rare cases, heavy users may become unpredictably violent, a psychological condition popularly known as 'roid rage.

Most of these unsightly and antisocial side effects subside when users stop dosing. But other effects worry members of the medical community more. "[Using steroids] blows the hell out of your good cholesterol," says Yesalis. Over time, such a drop could lead to trouble. "If [low good cholesterol] is maintained for protracted periods of time, we know from studies of non-steroid users that it will increase your risk of heart disease and stroke," he explains.

Common sense suggests that heavy steroid use is likely to increase those risks. "As the evidence emerges," says Yesalis, "you can make a stronger argument that higher doses for longer periods of time can lead to significantly worse health effects -- that's not rocket science."

But the most alarming evidence of the life-threatening dangers of steroids remains anecdotal. Doctors and researchers have documented hundreds of horror stories. In their luridly titled book, "Death in the Locker Room II," Dr. Bob Goldman and Dr. Ronald Klatz recount tales of steroid users cut down in their prime: a 33-year-old body builder who had a stroke and underwent a triple bypass, a high school football star who dropped dead of a heart attack, another bodybuilder in his 30s who came down with a rare kidney tumor and died months later. The book warns that "anabolic steroids bestow few benefits, and none worth the terrible risks of taking them." But Klatz now concedes that estimating the long-term risks of steroids is "like saying Iraq had weapons of mass destruction -- a distinct possibility, but so far nothing's turned up."

"A lot remains in realm of conjecture," says Dr. Harrison Pope, a Harvard psychiatrist. There's been plenty of research on steroids' effects on lab animals, but no one has done the kind of controlled, longitudinal epidemiological study in people that would show how these drugs affect users 20 or 30 years later. A major problem, says Pope, is money. "It's too expensive to research. It would cost millions do that type of study." Pope should know: In his 2000 book "The Adonis Complex," he announced that he and his colleagues were starting a study of middle-aged subjects who used to juice up regularly. But the funding for the study, he says, has evaporated.

Another problem is finding willing subjects. Pumping human subjects full of steroids would be unethical, and actual users aren't lining up to volunteer in the name of science. "Very few people are doing studies of human steroid abusers at all because they are very hard to recruit," explains Pope. "It is a very secretive subculture, and it's hard to get people to come forward."

Perhaps the best-known steroid user to go public was Lyle Alzado. Shortly before his death from brain cancer at age 43 in 1992, the two-time All Star defensive lineman suggested that his illness might have been caused by years of doping. "I know there's no written, documented proof that steroids and human growth hormone caused this cancer," he wrote in Sports Illustrated. "But it's one of the reasons you have to look at. You have to." Former NFL drug advisor Dr. Forest Tennant predicted ominously at the time that "Alzado will be the first of a lot of big names to come down with cancers."

Football players didn't start dropping like flies, but unconfirmed reports of steroid-induced afflictions continue to follow former NFL players, WWF wrestlers and Olympic athletes. Concerns resurfaced with the sudden death of Olympic sprinter Florence Griffith Joyner in 1999. While she was alive, there was grumbling that Flo-Jo's accomplishments on the track were boosted by steroids, which in turn led to rumors about the true cause of her death.

Schwarzenegger's health has inspired its own fair share of gossip. In 1997, at age 49, he had two aortic valves replaced, a procedure that he maintained was an elective fix for a congenital problem. That didn't stop a Berlin heart specialist from predicting the imminent demise of "a well-known Austrian actor" due to steroid-induced heart problems. Schwarzenegger responded to the uninvited prognosis with a lawsuit, and was awarded $10,000 by a German court. In 2000, he launched a $50 million defamation suit against the Globe tabloid for alleging that he was a "ticking time bomb," eventually settling out of court and receiving a retraction. But the rumors weren't terminated so easily. A 2001 Premiere magazine exposé on the actor quoted an unnamed doctor who speculated that Schwarzenegger's heart condition was brought on by anabolic steroids. Team Schwarzenegger rushed to deny the claim, insisting it was "bogus."

The murkiness surrounding steroids feeds this kind of sensational speculation, while also providing cover for former users like Schwarzenegger. The confusion is compounded by hardcore bodybuilders and trainers who insist that, when taken responsibly, anabolic steroids can be safe and even prolong life. "We emphasize use, not abuse!" asserts Sam "Doc" Phillips, whose Web site, AnabolicBeast.com, promises to help customers "get BIGGER and MORE RIPPED than ever, while reducing side-effects." Phillips' business partner, Author L. Rea (who also goes by the nickname "Beast Maker"), has made a name for himself in the bodybuilding world by promoting a complex regimen of controlled doping cycles. Philips is sanguine about the risks. "There aren't any 'long-term' effects because steroids are naturally occurring chemicals and hormones in the body," he claims, though he notes that steroid abuse may cause prostate growth, tweak cholesterol levels, and kill the libido. But overall, he says, the media, doctors and anti-drug groups have vastly exaggerated the dangers.

That view is echoed by Rick Collins, a New York defense lawyer who has been involved in more than a thousand steroid cases and is the author of the steroid-law handbook Legal Muscle. Collins says that stigmatizing steroids has exposed illicit users to greater risks. "One question is whether those potential health problems are made worse by the 1990 law," he says. "The answer is a resounding yes." Since the federal and state crackdown on steroids, most users no longer get their supply from doctors, as many old-school bodybuilders like Schwarzenegger did. "Instead of being screened and monitored and being checked for bad effects," says Collins, "basically users either get [steroids] from Internet Web sites or from Big Louie in the back of the gym."

What really remains to be seen is the long-term effects of steroids on one's political fitness. So far, the only available case study is that of wrestler-turned-Reform-Party maverick Jesse "The Body" Ventura. In his 1999 autobiography, released two months after his election as Minnesota governor, Ventura admitted that he'd taken testosterone during his previous career as a boa-wearing bad guy. The disclosure had little impact on his political career -- the implosion of which appears to have been triggered by his abnormally pumped-up ego, and temper.

So should Californians care that Schwarzenegger has taken steroids? Schwarzenegger rep Hanretty emphasizes that he'd prefer to focus on weightier subjects, like the economy. "These are the issues that matter most to Californians," she says.

Phillips, of AnabolicBeast.com, is adamant that steroids shouldn't be a political issue. "If one can become the president and have DUIs, then I certainly hope and pray that Arnold's past steroid use wouldn't be, or shouldn't be, an issue. Especially since he used it during a time when it was legal."

Similarly, researcher Yesalis finds scrutiny of Schwarzenegger's steroid use "disingenuous" given the lifestyle choices of other political figures. "What do I think of him as a role model? I don't think he's a terribly good one, but I was about a hundred times more offended by Bill Clinton," he says, suggesting that Clinton's hormone problem was on a different moral scale than Schwarzenegger's. If the media is going to examine Schwarzenegger's health, he suggests putting his recall rivals under the same microscope. "The leading cause of death is heart attack and strokes," he says. "Let's look at [Lt. Gov. Cruz] Bustamante. He looks like he's eating a lot. He looks like he's more than 30 pounds overweight -- that's obese."

However, comparing the roly-poly Bustamante with the Austrian Oak is a bit like comparing apples and orange Gatorade. Bustamante's body says little about who he is or what he stands for. But Schwarzenegger's body represents who he is, everything he's achieved: If he didn't have a great physique, would we even know who he is? Probably not. Anabolic steroids may or may not have affected Schwarzenegger's health or his suitability to be an elected official. But it's not too much of a stretch to say that he is still experiencing their effects. Look no further than his newfound political muscle.

Shares