When Bill Neel learned that President George W. Bush was making a Labor Day campaign visit to Pittsburgh last year to support local congressional candidates, the retired Pittsburgh steelworker decided that he would be on hand to protest the president's economic policies. Neel and his sister made a hand-lettered sign reading "The Bushes must love the poor -- they've made so many of us," and headed for a road where the motorcade would pass on the way from the airport to a Carpenters' Union training center.

He never got to display his sign for President Bush to see, though. As he stood among milling groups of Bush supporters, he was approached by a local police detective, who told him and his sister that because they were protesting, they had to move to a "free speech area," on orders of the U.S. Secret Service.

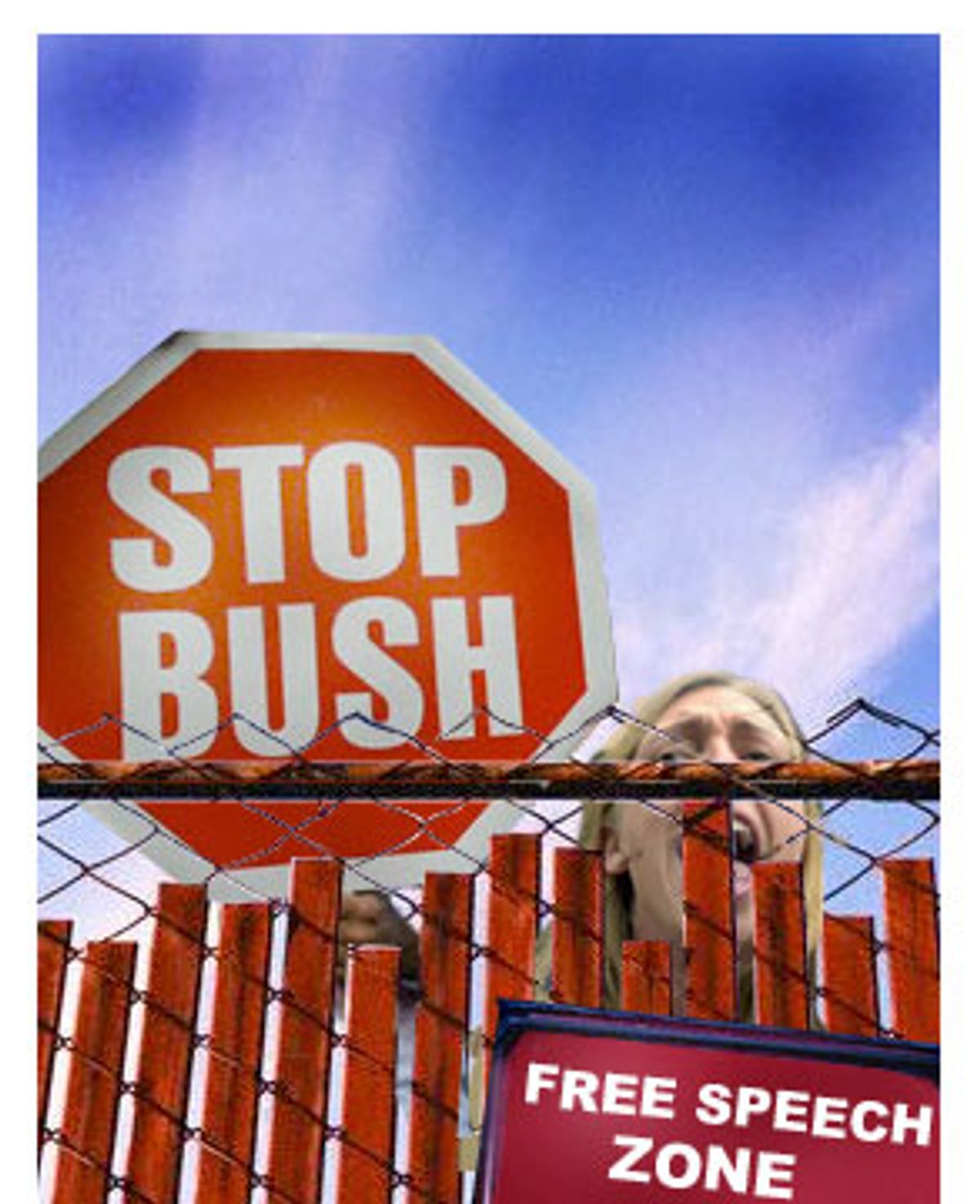

"He pointed out a relatively remote baseball diamond that was enclosed in a chain-link fence," Neel recalled in an interview with Salon. "I could see these people behind the fence, with their faces up against it, and their hands on the wire." (The ACLU posted photos of the demonstrators and supporters at that event on its Web site.) "It looked more like a concentration camp than a free speech area to me, so I said, 'I'm not going in there. I thought the whole country was a free speech area.'" The detective asked Neel, 66, to go to the area six or eight times, and when he politely refused, he handcuffed and arrested the retired steelworker on a charge of disorderly conduct. When Neel's sister argued against his arrest, she was cuffed and hauled off as well. The two spent the president's visit in a firehouse that was serving as Secret Service and police headquarters for the event.

It appears that the Neels' experience is not unique. Late last month, on Sept. 23, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit in a federal court in Philadelphia against the Secret Service, alleging that the agency, a unit of the new Homeland Security Department charged with protecting the president, vice president and other key government officials, instituted a policy in the months even before the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks of instructing local police to cordon off protesters from the president and Vice President Dick Cheney. Plaintiffs include the National Organization for Women, ACORN, USA Action and United for Justice, and groups and individuals who have been penned up during presidential visits, or arrested for refusing to go into a "free speech area," in places ranging from California to New Mexico, Missouri, Connecticut, New Jersey, South Carolina and elsewhere in Pennsylvania.

The ACLU, which began investigating Secret Service practices following Neel's arrest, has identified 17 separate incidents where protesters were segregated or removed during presidential or vice-presidential events, and Pittsburgh ACLU legal director Witold Walczak says, "I wouldn't be surprised if this is just the tip of the iceberg. We don't have the resources to follow Bush and Cheney everywhere they go." The suit also comes at a time of mounting charges by many civil libertarians on both the left and the right that the Bush Administration and Attorney General John Ashcroft's Justice Department are trampling on civil liberties.

"There is some history supporting the notion that all presidents dislike people who don't like them," says Stefan Presser, head of the ACLU of Philadelphia ACLU chapter and another lead attorney in the suit the Secret Service. "But this approach of fencing protesters in and removing them from view is unprecedented, and it's gotten worse over the past two years."

Well, maybe not exactly unprecedented. Pittsburgh's Walczak notes that during Nixon administration, especially during his second term, police "made quite a practice" of tearing up protest signs and confining protesters, and at least in one case that went to court, the Secret Service admitted being behind the actions. He says there were some isolated instances of interference with protesters during the Reagan administration, and even at President Clinton's inauguration, an attempt was made (unsuccessfully, thanks to ACLU intervention) to bar anti-abortion protesters from the inaugural march.

In its complaint, the ACLU cites nine cases since March 2001 in which protesters were quarantined. And it alleges that the Secret Service, with the assistance of state and local police, is systematically violating protesters' First Amendment rights via two methods. "Under the first form," the suit says, " the protesters are moved further away from the location of the official and/or the event, allowing people who express views that support the government to remain closer. Under the second form, everyone expressing a view -- either critical or supportive of the government -- is moved further away, leaving people who merely observe, but publicly express no view, to remain closer."

In either case, the complaint adds, "protesters are typically segregated into what are commonly referred to as 'protest zones.'"

In the ACLU's view, the strategy, besides violating a fundamental right of free speech and assembly, is damaging in two ways. "It insulates the government officials from seeing or hearing the protesters and vice-versa, and it gives to the media and the American public the appearance that there exists less dissent than there really is."

Certainly, as television cameras follow a presidential motorcade lined with cheering supporters, the image on the tube will be distorted if protesters have all been spirited away around a corner somewhere fenced in for the duration.

Contacted by Salon, the Secret Service denied that it discriminates against protesters. "The Secret Service is message-neutral," said spokesman John Gill. "We make no distinction on the basis of the purposes or intent of any group or the content of signs."

Further, Gill insisted that the establishment and oversight of local viewing areas during a presidential or vice presidential visit "is the responsibility of state and local law enforcement." In practice, it's apparently not that simple, though. Nor is the Secret Service's carefully worded denial of responsibility as definitive as it might appear. The "establishment of viewing areas" is indeed a local law enforcement responsibility, but local law enforcement officials say that the Secret Service has in some cases all but ordered them to pen in protesters. And it appears that the Secret Service is making recommendations about how that should be done.

Paul Wolf is an assistant supervisor in charge of operations at the Allegheny County Police Department and was involved in planning for the presidential visit to Pittsburgh last fall. He told Salon that the decision to pen in Bush critics like Neel originated with the Secret Service. "Generally, we don't put protesters inside enclosures," he said. "The only time I remember us doing that was a Ku Klux Klan rally, where there was an opposing rally, and we had to put up a fence to separate them.

"What the Secret Service does," he explained, "is they come in and do a site survey, and say, 'Here's a place where the people can be, and we'd like to have any protesters be put in a place that is able to be secured.' Someone, say our police chief, may have suggested the place, but the request to fence them in comes from the Secret Service. They run the show."

The statement by Wolf, who ranks just below the Allegheny County police chief, is backed up by the sworn testimony of the detective who arrested Neel. At a hearing in county court, Det. John Ianachione, testifying under oath, said that the Secret Service had instructed local police to herd into the enclosed so-called free-speech area "people that were there making a statement pretty much against the president and his views." Explaining further, he added: "If they were exhibiting themselves as a protester, they were to go in that area."

Asked to respond to the accounts of Wolf and Ianachione about the Secret Service's role in handling of protesters, spokesman Gill said only, "No comment." Asked pointedly whether Wolf's account was incorrect, Gill again said, "No comment."

Wolf also raises the possibility that White House operatives may be behind the moves to isolate and remove protesters from presidential events. He says that while he cannot recall specifically whether they were present with the Secret Service advance team before last year's presidential Labor Day visit, "I think they are sometimes part of" the planning process. The Secret Service declined to comment on this assertion, saying it would not discuss "security arrangements." The White House declined to comment on what role the White House staff plays in deciding how protesters at presidential events should be handled, referring all calls to the Secret Service.

Asked specifically whether White House officials have been behind requests to have protesters segregated and removed from the vicinity of presidential events, White House spokesman Allen Abney said, "No comment." But he added, "The White House staff and the Secret Service work together on a lot of things." While the Secret Service won't confirm that it is behind the pattern of tight constraints placed on protesters at public appearances by Bush and Cheney, the ACLU claims that mounting evidence suggests that this is exactly what is going on.

But the ACLU's lawsuit claims that the Secret Service is responsible for the tight constraints. A number of individual plaintiffs in the suit say that when they were directed into remote "free-speech areas," or arrested for refusing to go to such sites, they were informed that the local police were acting "on orders from the Secret Service."

That's the story Bill Ramsey got when he was arrested last Nov. 4 by police in St. Charles, Mo., while attempting to unfurl an antiwar banner amid a group of pro-Bush people during a presidential visit to a local airport. "The police told us if we wanted to show the banner, we'd have to go to a parking lot four-tenths of a mile away and out of sight of the president's motorcade," says Ramsey. When we attempted to put it up anyway, they arrested us, and said they'd been ordered to by the Secret Service."

But Ramsey says that when his organization, the Instead of War Coalition, has sought to obtain permission to hold its demonstrations during presidential visits, they are told by the Secret Service that such matters are the responsibility of local police. "When we go to the local police, though, they say it's up to the Secret Service."

Efforts to obtain a comment from the St. Charles Police Department were unsuccessful.

Andrew Wimmer, another member of the Instead of War Coalition, says he was offered a similar explanation last January in St. Louis when he attempted to unfurl a sign reading "Instead of War, Invest in People" on a street full of Bush supporters. According to Wimmer, St. Louis police officers told him he'd have to leave a street full of Bush supporters and go to a protest area two blocks from the presidential motorcade route because of his protest sign. He recalls that as crowds of people walked down a thoroughfare toward the trading company that President Bush was slated to visit, "local police were pulling out people carrying protest signs and directing them to the protest area." The 48-year-old IT worker says, "When they got to me, I said no, I'd just as soon stand with the people here. But they said the Secret Service wanted protesters in the protest area."

In the end, Wimmer, like Ramsey and others who have refused to be caged during protests, was arrested. "They charged me with obstructing passage with my sign, which was a 2.5-foot-by-2-foot lawn sign," he says, noting that a woman standing nearby with a similar-size sign saying "We love you Mr. President," was left alone.

"The Secret Service keeps saying that the decision to separate protesters and remove them from view is a local police matter," says Denise Lieberman, legal director of the ACLU of Eastern Missouri, who is representing both Ramsey and Wimmer in their arrest cases. "But these kinds of things only happen when the Secret Service is involved. We've had many visits to St. Louis -- by the pope, by candidates, by dignitaries -- and it's only when the president or the vice president come to town that this kind of thing happens."

"We expect to see a lot more of this heading into a campaign season," says Chris Hansen, senior staff attorney at the ACLU and one of the lead attorneys handling the suit against the Secret Service.

Presser, the Philadelphia ACLU attorney, traces the tactic to the last Republican National Convention, which nominated Bush for the presidency in August 2000. "The GOP tried to reserve every possible space where a protest group might rally," Presser recalls. "Part of the party's contract with the city of Philadelphia for the convention was that they were given an omnibus permit to use 'all available space' for the two weeks of the convention. They basically privatized the city to block all legal protest."

During that convention, the city attempted to require all groups seeking to protest during the convention to apply for permits to get a 15-minute protest time slot, during which they would be allowed to assemble and make their statement in a sunken "protest pit," remote from the Convention Center. Many groups refused, and the result was a series of conflicts with local police and many arrests, most of which were later tossed out by the courts.

Since then, Presser charges, the Bush administration has continued the strategy of using the Secret Service and cooperative local police departments to keep protesters at bay, and not incidentally, out of easy range of the media. "People used to say that Ronald Reagan's was the most scripted administration we ever had," the attorney says, "but this Bush administration has gone way beyond that." Presser adds that he was told by William Fisher, a senior Philadelphia police captain and head of the department's Civil Affairs Unit, that the tight restrictions and decision to cordon off protesters during presidential visits have come "at the Secret Service's direction." Fisher declined to be interviewed for this article, but when asked, did not deny Presser's account of their conversation.

Presser and the ACLU don't question the Secret Service's responsibility to protect the president and other key government officials. Even plaintiffs in the case agree that the president must be protected. But "putting protesters behind a fence isn't going to help," says Neel, the former Pittsburgh steelworker. "I mean, somebody who was going to attempt an assassination wouldn't be carrying a protest sign. He'd be carrying a sign saying 'I love George!'"

The ACLU's Presser agrees. "Just as the terrorists who attacked the World Trade Center were careful to blend in and stayed away from mosques," he says, "anyone who had ill will towards the president could just put on a pro-Bush T-shirt and, under this policy, he'd be allowed to move closer to the president by the Secret Service."

He adds, "It seems that these 'security zones' for protesters have very little to do with the president's physical security, and a whole lot to do with his political security." Asked how many times in history an attack had been made on a president or other official under Secret Service protection by someone clearly identifiable as a protester, agency spokesman Gill said, "I'm not going to comment on that." Interestingly, Gill at no point claimed that protesters posed a special threat to the president or vice president.

Whatever the real motives behind it, the Secret Service policy of fencing off protests and protesters during presidential events may be in for a tough challenge. The judge assigned to the case, John Fullam, is an appointee of former President Lyndon B. Johnson, and back in the late 1980s issued a permanent injunction in Philadelphia -- still in effect -- that bars both the city of Philadelphia and the National Parks Department (the agency in charge of the city's many federal monuments), from treating protesters or people wearing protest paraphernalia any differently from other citizens.

The ACLU, which is seeking an injunction barring the Secret Service and local police from treating protesters differently from other spectators at administration events, is hopeful that the court will act "before the presidential campaign gets into full swing next summer," says Walczak. Meanwhile, Presser says he is optimistic that the lawsuit, simply by being filed, could make things easier for protesters during the coming campaign season."I suspect that this suit may give the Secret Service and local police some pause in how they treat protests," he says.

Shares