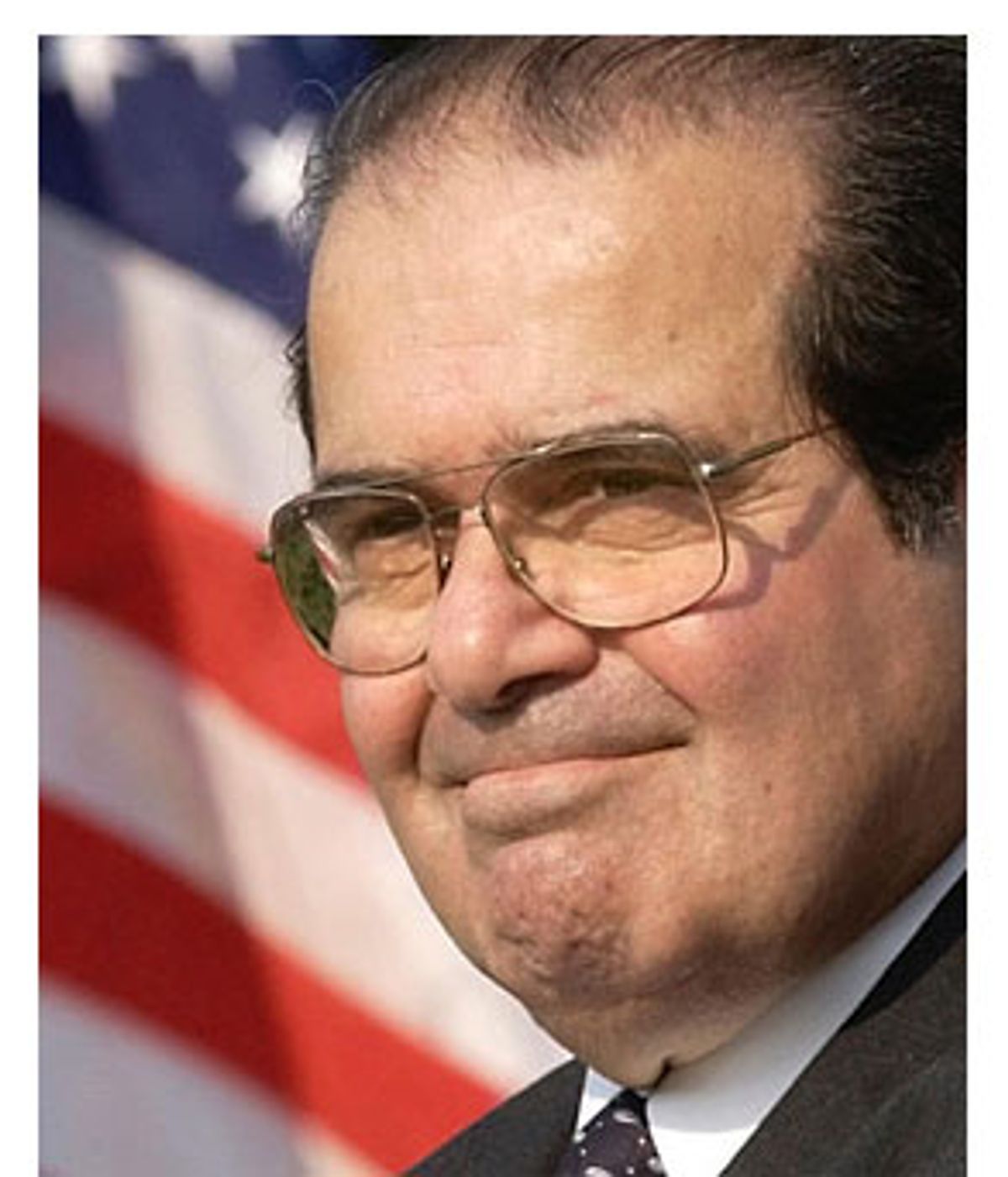

As he travels the country speaking to law schools and religious groups, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia likes to say that the U.S. Constitution is dead. It's not a "living document" whose meaning changes with the "evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society," but rather a set of rules established once and for all in 1789. The Constitution, Scalia says, means "what it meant when it was adopted."

But even for a jurist rooted so deep in the past, there comes a time to think of the future. For Scalia, that time came on the morning of Dec. 9, 2000. The Florida Supreme Court had just ordered a manual recount of more than 40,000 undervotes in the 2000 presidential election. George W. Bush, who was leading Al Gore in Florida by just 537 votes at the time, wanted that recount stopped -- immediately.

Five Republican Supreme Court justices obliged, and Scalia took it upon himself to explain why. Counting the votes, Scalia wrote, would "threaten irreparable harm to petitioner, and to the country, by casting a cloud upon what he claims to the legitimacy of his election. Count first, and rule upon legality afterwards, is not a recipe for producing election results that have the public acceptance democratic stability requires."

As he wrote those words that Saturday morning, Scalia was clearly thinking about Bush's future. It's hard to imagine that he wasn't also thinking of his own.

Scalia was a centerpiece of the 2000 presidential race. Candidate Bush had named him as a model of the sort of judge he'd like to appoint, and Democrats had raised the scary specter of "Chief Justice Antonin Scalia" as a way to mobilize their base. When the election came before the court, surely Scalia saw some personal advantage in helping Bush -- more conservative justices to side with him, perhaps, or maybe even a chance to lead them as the new chief justice.

It hasn't turned out that way.

Three and a half years into the Bush presidency, Antonin Scalia is an increasingly marginalized player on the U.S. Supreme Court. With no new justices having joined him -- and his old Republican colleagues proving to be unreliable allies -- Scalia is more and more often on the losing side of close decisions. A Bush victory in November would almost certainly change the makeup of the court; Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Associate Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and John Paul Stevens will probably retire soon, and if they do so in the next four years Bush could provide Scalia with fellow justices ready to hew to his traditionalist right-wing views. But Scalia's outbursts -- his outraged dissents in cases on affirmative action and gay rights, his impassioned out-of-court talks like the one that led to his recusal from last week's Pledge of Allegiance case, and his contemptuous handling of the charges of impropriety arising from his decision to go duck hunting with Dick Cheney at a time when the vice president was a party in a case before the court -- make it less and less likely that Bush will appoint Scalia chief justice or that the Senate would confirm him if he did.

It's hard to know exactly why Scalia hasn't been more successful in leading a conservative revolution on the court. It could be that his views are simply too extreme to draw four supporting votes on a consistent basis. While more mainstream Republican judges like O'Connor and Anthony Kennedy may buy into the notion that societies progress and mature, Scalia maintains his allegiance to traditional values and the political views of the Founding Fathers. He also obeys the pronouncements of the Catholic Church -- he is rumored to be a member of the conservative Catholic group Opus Dei -- except with respect to the death penalty, where Scalia thinks the modern church has simply got the Bible wrong. (In a speech that became an article in the journal First Things in 2002, Scalia said that judges who believe the death penalty is immoral should resign from the bench.)

But the lack of success in leading his colleagues could also stem from Scalia's sledgehammer approach to writing opinions. Karl Rove and George W. Bush understand that even extreme right-wing views can be palmed off on the populace if they're wrapped up in the language of "compassionate conservatism" and articulated with a smile. Maybe that lesson has been lost on Scalia -- or maybe he just doesn't care.

Bush may see in Scalia a man of principle, but over the last nine months the most outspoken member of the Supreme Court has become a poster child for sputtering vitriol, questionable ethics and the intolerant rant.

Seven years ago, political scientist Richard Brisbin wrote a book exploring Scalia's role as a visionary leader of America's "conservative revival." Today, he is considerably more bearish on his subject. Given the lightning-rod aspects of Scalia's behavior and the closely divided nature of the U.S. Senate, Brisbin says that Scalia's "future prospects are to be an associate justice as long as he wants to be an associate justice."

And Brisbin isn't alone in that view; former clerks to the 68-year-old justice say Scalia himself probably shares it. "I think that having the court called the 'Scalia Court' would appeal to him as it would to any other justice," says Northwestern University law professor Steven Calabresi, who served as one of Scalia's first Supreme Court clerks. "But I think he's realistic enough to know that there are all sorts of reasons why, even if the president wanted to name him chief justice, it might make sense not to do it."

In 1986, Chief Justice Warren Burger gave Ronald Reagan the same opportunity that virtually every legal observer in the country predicted that William Rehnquist would have given George W. Bush by now. Burger retired, clearing the way for Reagan to name a new chief justice from the ranks of associate justices, and a new associate justice to take his place. Reagan nominated Rehnquist to the chief's chair, and Scalia to take Rehnquist's spot as associate justice.

Improbable as it seems today, the Rehnquist nomination was the more controversial of the two. Liberals worried that Rehnquist was too conservative, and he was dogged by a memo he wrote as a law clerk in 1952 -- one in which he seemed to argue that the Supreme Court should hew to the "separate but equal" standard of Plessy vs. Ferguson in the then-pending case of Brown vs. Board of Education. The Senate debate was contentious, but Rehnquist was confirmed by a vote of 65-33.

With the Senate distracted by the Rehnquist fracas, Scalia skated through the confirmation process. He was confirmed unanimously, 98-0, and the two senators who weren't on the floor to vote were Republicans who would have voted for him anyway. Al Gore and John Kerry were both in the Senate at the time; both voted to confirm Scalia.

In a speech last month in New Orleans, Scalia contrasted his easy ride to confirmation with the tough sledding some of Bush's nominees have faced. "Eighteen years ago, I was confirmed 98-0," Scalia said. "I was considered a good lawyer and an honest man. Those qualities carried the day."

Those may have been the qualities that led to Scalia's confirmation, but the new associate justice acted as if the Senate had given him a mandate to reshape the Supreme Court in his conservative image -- and to do so in his own aggressive way. As the story is told in John Jeffries' biography of Justice Lewis Powell, Scalia so dominated his first session on the Supreme Court bench that Powell turned to Thurgood Marshall and asked: "Do you think he knows that the rest of us are here?"

In the 18 years since then, Scalia has certainly learned of the existence of the other justices, if not the need to make nice to them. In his drive to keep constitutional interpretation frozen in the aspic of 1789 -- and in his allegiance to a moral agenda that disapproves of abortion, homosexuality and other modern vices -- Scalia has frequently found himself at odds with the majority of even this conservative court. In the term that ended in June, Scalia dissented 16 times, second only to Clarence Thomas' 21.

And from the very first days of his tenure on the court, when Scalia has disagreed with the majority, he has not been the least bit shy about saying so. Indeed, he quickly established himself as the most vigorous dissenter, a role he plays with increasingly frequency.

Within months of Scalia's swearing in, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Edwards vs. Aguillard, a case concerning the constitutionality of a Louisiana law that required the teaching of creationism in any school that also taught evolution. Seven justices agreed that the law violated the First Amendment's prohibition against the establishment of religion. Scalia disagreed, railing against the majority for repressing Christian fundamentalists and pointing to "uncontradicted testimony that 'creation science' is a body of scientific knowledge rather than revealed belief." Scalia, with Rehnquist joining in, pronounced the jurisprudence on religious freedom "embarrassing."

Cass Sunstein, a leading scholar of constitutional law at the University of Chicago, said that Scalia is "one of the best writers in the court's history," but that he'd be even better if he showed at least some tolerance for opposing views. "He has a definite defect, which is insufficient appreciation that reasonable people disagree with him," Sunstein says. "His opinions would be much stronger if they were permeated with an awareness that reasonable people who disagree with him happen to be wrong, rather than -- as he occasionally portrays them -- lawless or buffoonish."

Michael Ramsey, a former clerk for Scalia who now teaches law at the University of San Diego, has a more positive take on Scalia's negativity. "When he's confident about an outcome, he doesn't beat around the bush in order to assuage people's feelings," Ramsey said. "When he sees an argument that he sees as a stupid argument, he treats it like a stupid argument, which is what he thinks it merits."

Justice O'Connor is the most frequent target of the "stupid argument" treatment. Although O'Connor, like Scalia, was appointed by Reagan, she passes for a centrist on this conservative court. In close cases, she is almost always the pivot point on which hard decisions turn. If O'Connor votes with the conservatives, they win 5-4. If she votes with the liberals, they win 5-4. According to one analysis, O'Connor was in the majority in each and every one of the court's 5-4 decisions in the 2003 term.

For Scalia, O'Connor's "defections" are particularly galling, and he rails vigorously against her whenever she strays. As one experienced Supreme Court practitioner put it in an e-mail exchange with Salon last week, Scalia's "'Sandy, you dumb broad...' opinions have been masterpieces of contemptuous nastiness for more than a decade."

O'Connor says the attacks don't bother her. In an appearance on ABC's "This Week" last summer, she said: "When you work in a small group that size, you have to get along, and so you're not going to let some harsh language, some dissenting opinion, affect a personal relationship." Still, it's hard to imagine that Scalia's brow-beating has made O'Connor more inclined to vote with him, particularly as Scalia's dissents veer, as they sometimes do, perilously close to the realm of ad hominem attacks. In 1989, for example, while advocating the reversal of Roe vs. Wade, Scalia accused O'Connor of results-oriented judging, said her assertions could not be taken seriously, and closed by stating that O'Connor's efforts were "simply irrational."

Scalia was just getting started. Vik Amar, a professor at the University of California's Hastings College of the Law, says that, over the top as Scalia's rhetoric was in the early stages of his tenure, he reached a sort of carping crescendo in 1996, when he dissented in high-profile cases involving gender discrimination and gay rights.

In United States vs. Virginia, a case in which seven justices agreed that Virginia must open the previously all-male Virginia Military Institute to female students, Scalia exploded in rage over his notion that a "self-righteous Supreme Court, acting on its own Members' personal view of what would make a 'more perfect union' ... can impose its own favored social and economic dispositions nationwide."

And in Romer vs. Evans, in which six justices invalidated a Colorado constitutional amendment that prohibited any government entity from offering legal protections to homosexuals, Scalia reached for the weapons of class warfare in defense of anti-gay prejudice. "This Court," Scalia wrote, "has no business imposing upon all Americans the resolution favored by the elite class from which the Members of this institution are selected, pronouncing that 'animosity' toward homosexuality is evil. I vigorously dissent." Looking back, Amar says, "These were a couple of cases where it became clear to Scalia and to the world that he was never going to be effective at convincing the middle justices to form a reliable majority for his constitutional vision." Amar, who clerked for Justice Harry Blackmun in 1990, said Scalia's dissents in 1996 "marked his marginalization in some way in building majorities."

If conservative columnist Robert Novak is to be believed, Scalia was smarting from his "marginalization" as the Clinton era came to a close. In an unsourced report written in April 2000, Novak cited rumors that Scalia would step down from the court if Al Gore were elected president. "Scalia, the Supreme Court's conservative anchor, was dissatisfied with his colleagues even before President Clinton named two liberals to the nine-judge court," Novak wrote. "If Gore is elected with the prospect of naming still more liberals, Scalia's frustration could be too much, and he may call it a judicial career."

That's not how it happened, of course. While Gore unquestionably won the popular vote in 2000, Scalia, Thomas, Rehnquist, Kennedy and O'Connor intervened in the election just in time to prevent the nation from knowing who really won Florida -- and with it the Electoral College votes needed to take the White House.

By all rights, Bush vs. Gore should have marked the beginning of Scalia's climb back to power on the Supreme Court. During the campaign, Texas Gov. George W. Bush found it necessary to assure his base that he wouldn't make his father's mistake of appointing a moderate in conservative's clothing like David Souter. He did so by invoking the names of Scalia and his right-wingman, Clarence Thomas, as role models for future judicial appointments.

And by the time Bush took office in January 2001, it looked as though he would have as many as three chances to put Scalia clones on the Supreme Court. With a Republican in the White House, Rehnquist and O'Connor were sure to retire. The liberal John Paul Stevens, who will turn 84 in April, wouldn't be happy about giving Bush the power to name his replacement, but he might not have a choice.

None of that has happened, and barring a sudden health crisis or death, none of it is going to happen before the November election. Scalia has gained no new Republican colleagues on the court, and he seems to be losing influence over the ones he already has. Since the court's 2000 term, which began three months before Bush took office, Scalia's conservative bloc has steadily lost its grip on the court's closest cases. An analysis by a Supreme Court practitioner who monitors court statistics shows that, in 2000, the conservative bloc prevailed in 54 percent of the court's 5-4 decisions. In 2001, the conservatives controlled 48 percent of those cases. And in the 2002 term, which ended in June, the conservatives won just 40 percent of the 5-4 votes.

During the 2000 term, the most liberal justices were the most frequent dissenters. By the time the 2003 term ended, Scalia and Thomas were.

The need to dissent so often would be deeply disappointing to someone like the late Justice William Brennan, who aimed to push and pull his colleagues toward the "right" outcomes through persuasion, politicking and compromise. That has never been Scalia's style. A lawyer who clerked for Scalia says his old boss is focused solely on getting the decision right, even if attention to the tiniest arcane detail risks putting off other justices. "It does translate into a difference in ability to move others within the court," the former clerk said. "Brennan was a master at that because he never made enemies and because he didn't project certitude about his views. Justice Scalia is more concerned about 'getting it right,' even if it means not carrying the day. It's a brand of integrity that at some level is admirable."

At some level, it may be. But over the last nine months, Scalia himself has turned up the volume on his vitriol so high that it's hard to hear anything else. Scalia's latest round of rants began in June. In a single week, Scalia issued fiery dissents in three cases. He attacked as a "sham" an affirmative action program approved by a majority of the court, saying that the justification for the program "challenges even the most gullible mind." He argued that the majority's reasons for reversing the death penalty in an ineffective-assistance-of-counsel case range[d] from the incredible up to the feeble."

And in Lawrence vs. Texas, in which the court invalidated laws criminalizing sodomy among consenting adults, Scalia accused his colleagues of having signed on to "the so-called homosexual agenda" and "taken sides in the culture war" against people who simply want to protect "themselves and their families from a lifestyle that they believe to be immoral and destructive."

Scalia dissented in whole or in part six more times in a single week earlier this year. At the same time, Scalia has been making the rounds of the speakers' circuit -- in a speech last week at the College of William and Mary, he said that his colleagues on the court have fallen under the spell of the "enormously seductive living Constitution." All the while, he is working to patch up problems caused by his earlier extrajudicial activities.

As a result of off-the-cuff comments last year in which he said that the words "under God" could be removed from the Pledge of Allegiance only by democratic action and not judicial fiat, Scalia had little choice but to recuse himself from any participation in the Pledge case heard by the court last week. But just as the remaining eight justices were preparing to take oral arguments on that case, Scalia issued his extraordinary memorandum refusing to recuse himself from another case: the one challenging the administration's refusal to release records related to Vice President Cheney's energy task force.

Although Scalia acknowledged that he is a friend of Cheney's, flew to Louisiana as a guest of Cheney on an Air Force plane, and spent a few days hunting ducks with Cheney and a small group of friends -- including an energy company executive -- Scalia proclaimed that no reasonable person could possibly question his impartiality in the case. Scalia's 21-page memorandum was just as dismissive of concerns raised by the press, the public and the Sierra Club as he has ever been of O'Connor.

But remarkably, the Scalia memorandum took a more reasoned approach than that taken on two previous occasions in which Scalia addressed the Cheney issue. In a letter he wrote to the Los Angeles Times in January, Scalia said that the question of whether he should recuse himself was the third toughest the Times had put to him. The first two: How was the duck hunting? and, Was Dick Cheney on the trip with you?

And when he was asked about the alleged conflict of interest during a talk at Amherst College in February, Scalia said: "It's acceptable practice to socialize with executive branch officials when there are not personal claims against them. That's all I'm going to say for now. Quack quack." It wasn't quite "What's the frequency, Kenneth?" but in the world of oddball pronouncements from public figures, Scalia's birdcalls came close.

In his more sober memorandum refusing to recuse himself from the Cheney case, Scalia complained that he had been victimized. "I have received a good deal of embarrassing criticism and adverse publicity in connection with the matters at issue here -- even to the point of becoming (as the motion cruelly but accurately states) -- the 'fodder for late-night comedians.' If I could have done so in good conscience, I would have been pleased to demonstrate my integrity, and immediately silence the criticism, by getting off the case. Since I believe there is no basis for recusal, I cannot."

To be fair to Scalia, reasonable lawyers differ on whether he should have recused himself in the Cheney case. But there's not a whisper of reasonable disagreement in Scalia's memorandum. The truth is solely as he construes it, and there is simply no reasonable argument to the contrary.

Scalia's decision not to recuse himself keeps him on the bench to hear the Cheney case, but it surely won't help him climb any higher. If Rehnquist retires in the next four years, President Bush or President Kerry will have the opportunity to appoint a new chief justice. There's no chance that Kerry would choose Scalia. But Scalia's refusal to recuse himself in Cheney's case hurt his chances in any case, said Calabresi, Scalia's former clerk: "I think this makes it harder for President Bush to nominate him for chief justice, and it would be an issue in any confirmation hearing," As with so much else Scalia has said and done, the Cheney recusal memo may ultimately work against his long-term interests -- at least if those interests include becoming chief justice of the United States.

Shares