As the war in Iraq seemed to spiral out of control -- with more than 30 U.S. soldiers and hundreds of Iraqis killed since the weekend, with the charred corpses of American citizens hanging from a bridge in Fallujah and Iraqi kidnappers threatening to burn foreigners alive, with Shiite and Sunni uprisings making a mockery of Bush administration claims that Americans would be "greeted as liberators" -- Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry traveled to Washington Wednesday to deliver a major policy address at Georgetown University. His subject: the federal budget deficit.

The subject was much the same for the Kerry campaign all week. This was the week Kerry campaign planners penciled in budget talk, and they weren't about to let the war bump them off message. For much of the week, the only hint of Iraq on the Kerry campaign's home page was a small-type link to a speech Kerry gave in Iowa when Saddam Hussein was captured four months ago. On Thursday morning, the Web site featured a waving American flag and a milquetoast comment from Kerry minimizing his differences with the president and honoring the sacrifices of fallen soldiers.

And even when Iraq fit into Kerry's budget message, the Kerry camp steered clear of it. Explaining the absence of Iraq funding in a budget analysis the campaign released this week, Kerry surrogate Sen. Jon Corzine said: "We wanted to make sure this wasn't focused on the debate about whether we should or shouldn't support our troops."

Iraq is exploding in Bush's lap, but Kerry seems to be the one running scared. Although Kerry has made sporadic comments about Iraq throughout the week -- in a radio interview Wednesday, he called the war "one of the greatest failures of diplomacy and failures of judgment that I have seen in all the time that I've been in public life," and on Thursday he repeated his attack on Bush's unilateralist approach to the war -- he has not made the war a centerpiece of his campaign. As a young naval officer just back from Vietnam, John Kerry had the courage to help lead the nation out of one misguided military adventure; as a U.S. senator and presidential candidate, why is Kerry so cautious, so careful, so tentative now?

Maybe the Kerry campaign feels trapped by the senator's own record on Iraq; he voted to authorize the use of force in Iraq in October, then voted against $87.5 billion in funding for the war. Maybe the ghost of Howard Dean haunts the campaign. Maybe Kerry's advisors fear that Bush administration smears -- Kerry is an appeaser, Kerry will cut and run, Kerry won't support the troops -- might begin to stick. A spokesman for the Kerry campaign seemed to acknowledge as much Thursday, saying that the campaign did not want to expose itself to charges of politicizing the war.

Or maybe the Kerry campaign believes -- and not unreasonably -- that the war is going so badly now that there's no need to say much about it. Public support for Bush's handling of the war has dropped from 59 percent in January to 40 percent in a new Pew Center poll -- and that poll was released early this week, before the TV news brought home stories of substantial U.S. casualties in Iraq.

"I think Kerry's letting George Bush beat himself, just standing aside and letting events diminish Bush's leadership," says Jeffrey Berry, a political science professor at Tufts University who follows Massachusetts politics -- and, hence, Kerry -- closely. "That's part of a workable strategy, but there's another piece missing."

That other piece, Berry and other analysts say, is an affirmative case for Kerry. It is one thing to say that Bush has led us into a new Vietnam, as Sen. Edward Kennedy said earlier this week. It is quite another to explain how Kerry might lead us out of it.

Kerry must have known that he'd be pressed on the latter point as he made the radio and TV rounds promoting his budget policies this week. But when the question was put to him, Kerry appeared to be caught flat-footed. When asked Wednesday what he would be doing differently in Iraq, the challenger produced a stumbling non-sequitur of a response more typical of his opponent. "Right now," Kerry said, "what I would do differently is, I mean, look, I'm not the president, and I didn't create this mess, so I don't want to acknowledge a mistake I haven't made."

A Kerry spokesman told Salon on Thursday that it's incumbent on Bush -- not Kerry -- to address the crisis in Iraq. "What has the president said about this?" the Kerry spokesman asked. "He needs to explain what his policy is, what his plan is to address what's going on right now. But he's been down on his ranch in Crawford. The spotlight isn't on John Kerry. The spotlight needs to be on Bush. He's the president, and he's the person who has carved out these policies."

That's certainly true, but it's also true that Kerry wants to be elected president himself. To get there, he's going to have to offer a clear alternative to Bush. He did that this week on budget issues, but he has had much greater difficulty when it comes to the war on Iraq.

During the primaries, Kerry struggled almost daily to explain his views on the war. As Dean surged in the polls with a strong antiwar message, Kerry was forced to explain away his October 2002 vote in favor of the use-of-force resolution by claiming that he had meant to authorize only the credible threat of the use of force. He then struggled to square that vote with his vote against Bush's proposal for $87 billion in funding for Iraq and Afghanistan. In an interview with a New York Times reporter last fall, it took Kerry nearly 40 minutes to come up with something approaching a coherent theory explaining the two votes.

Kerry made matters worse for himself last month, when he handed Karl Rove and the Bush campaign a made-for-TV sound bite on Iraq. Kerry was trying to explain to supporters that he had voted for a version of the $87 billion Iraq and Afghanistan package that would have been funded by rolling back some of Bush's tax cuts, but that he had voted against the final version of the bill because it did not contain the tax-cut rollback or any other way to pay for the war. Instead of that reasonable explanation, what came out of Kerry's mouth was: "I actually did vote for the $87 billion, before I voted against it."

The Bush campaign jumped on the remark, inserting it almost instantly into a TV commercial painting Kerry as "wrong on defense." Perhaps Kerry's stumbles make the campaign wary about moving too quickly on Iraq; it was Thursday before Kerry was offering anything like a full-throated response to the events of the week.

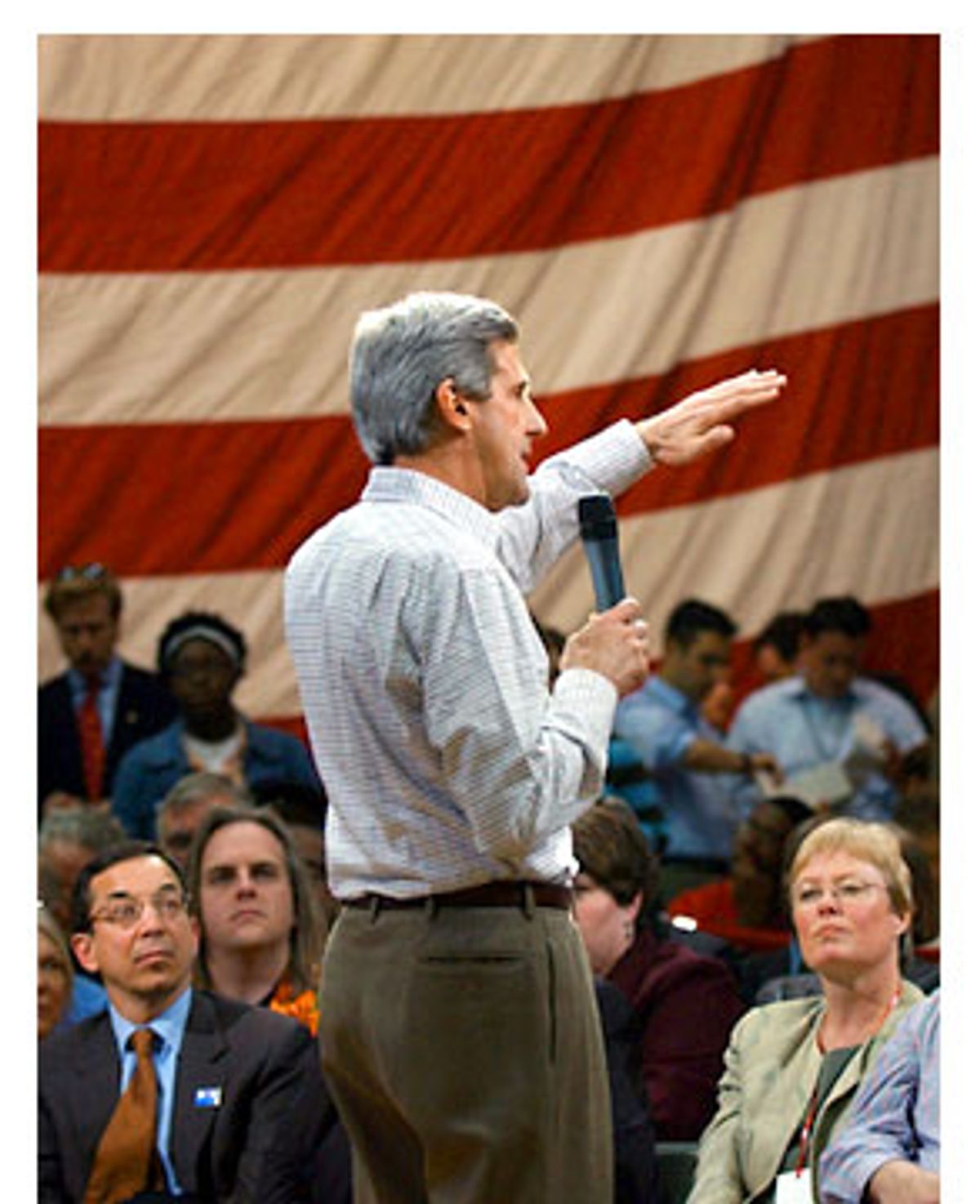

At a town hall meeting in Milwaukee Thursday -- again, an event focused on economic issues -- Kerry pressed for a renewed effort at international cooperation in Iraq. He said the United States "ought to be engaged in a bold, clear, startlingly honest appeal" to other countries to see their own interests at risk in Iraq and to come to the aid of the U.S. war effort.

"I believe it is the role of the president of the United States to maximize the ability to be successful and to minimize the cost to the American people, both financially and in lives," Kerry said. "That's common sense. And here today, once again, we are asking the question, why is the United States of America almost alone in carrying this burden and the risks which the world has a stake in?"

It was exactly the sort of affirmative pitch Kerry needed to throw, but it took him nearly a week to wind up. The Kerry campaign seems to have forgotten the respond-in-the-same-news-cycle lesson of the Clinton war room. Worse still, the Bush campaign seems to have taken that lesson to heart. Every time Kerry or his surrogates have spoken out on Iraq, Bush and his supporters have been quick to hit back hard.

When Kerry suggested that Bush's June 30 deadline for turning over sovereignty to Iraqis might be driven by domestic political concerns, White House spokesman Steve Schmidt accused Kerry of "playing politics with the war on terror." And after Kennedy called Iraq "George Bush's Vietnam," Secretary of State Colin Powell said the senator "should be a little more restrained and careful in his comments because we are at war." Powell's warning echoed comments other Republicans made at the beginning of the war. Last spring, when Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle expressed regret that Bush's failed diplomacy was leading the country to war, House Speaker Dennis Hastert accused him of coming "mighty close" to giving "comfort to the enemy."

Bush is running as a war president. But under the Republicans' rules of engagement, it appears that only those who support the president in the war are free to make a political issue out of his handling of the war. It hasn't always been so. During World War II, for example, Republican presidential candidate Thomas Dewey harshly criticized Franklin Delano Roosevelt for his war effort. Dewey even came close to blaming FDR for Pearl Harbor until "patriotism and fear caused him to back down," said Claremont McKenna College professor Jack Pitney.

Pitney's "Political Warfare During Wartime," will appear in a forthcoming collection of essays titled "High Risk and Big Ambition: The Early Presidency of George W. Bush." In conducting his research for the essay, Pitney -- a former Republican National Committee official who once worked for Dick Cheney -- said he was surprised to find a rich history of dissent during political campaigns in times of war. "There's a myth that politics was adjourned for the duration of the Second World War," he said.

More recently, during the 1980 presidential campaign, both Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush challenged President Jimmy Carter on his handling of the Iranian hostage crisis. During the Republican primaries, Bush said: "I know appeasement is a tough word -- but let's call the Carter program of backing, filling and hand-wringing exactly what it is." And in a debate a week before the election -- when 51 Americans were still being held hostage in Iran -- Reagan went after Carter in words that resonate today. He blamed Carter for "not heeding warnings about a threat to the embassy" and demanded a congressional investigation into Carter's handling of the crisis. He asked: "Is America as respected throughout the world as it was four years ago?"

And in the Clinton years, Republicans repeatedly attacked the president during military operations in Bosnia, Kosovo and elsewhere. When Clinton ordered a missile attack on suspected terrorist targets in the Sudan and Afghanistan in 1998, some Republicans accused him of "wagging the dog" to distract attention from the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Republicans made similar charges months later, when British and American forces participated in a joint bombing attack on Iraq while the House of Representatives was considering impeachment charges against Clinton.

There's a way to do these things without crossing the line, Pitney says, and he believes Reagan got it right. By "posing questions rather than making attacks," a candidate in wartime can make his points without "sounding disrespectful of the president or the troops," he said. "That's really the basic dilemma of a challenger during wartime -- how far can you criticize the president without undermining the war effort and risking a serious backlash?" Pitney said.

One way to avoid the backlash is to leave the heavy lifting to surrogates. So far, Kerry seems to have dumped the Iraq duty on Ted Kennedy, who delivered a seething indictment of the Bush administration at a Brookings Institution speech Monday. But some analysts question whether the liberal Kennedy is the right man for the job; while he has achieved "elder statesman" status among those on the left, his iconic reputation as a Massachusetts liberal may leave him ineffective with swing voters wavering on Iraq. To appeal to such voters, Berry said Kerry needs the vocal support of experienced foreign policy hands like former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, former National Security Advisor Sandy Berger and Sen. Joseph Biden. "Kerry needs an array of senior statesmen, people involved in diplomacy, in war, in intelligence, to drive home the point that there's a real threat from al-Qaida, that we have to keep working on that harder and harder, but that that's something separate from going to war in Iraq," Berry said.

Kerry could also use the backing of two of his former adversaries in the Democratic presidential primaries: retired Gen. Wesley Clark and Iraq hawk Sen. Joseph Lieberman. Neither Clark nor Lieberman has come rushing to Kerry's aid on Iraq yet. Indeed, Lieberman issued a statement Wednesday that seemed to undercut any efforts Kerry might make to distinguish himself from Bush on plans for the war. He urged "President Bush and Senator Kerry to reach common ground on the issue of sending more troops to Iraq," and warned that any delay in "doing the right thing" would "only increase the risk and danger that both our troops and the Iraqi people face."

Lieberman noted that both Bush and Kerry have vowed that the United States will not "cut and run" from Iraq. And in the end, it is that vow -- that commonality of policy positions -- that keeps Kerry from striking out more clearly on Iraq. Kerry voted to give Bush the authority to go to war, and he agrees that troops need to stay in Iraq until the country is made stable again. With 44 percent of the American public now wanting to bring U.S. troops home "as soon as possible" -- as opposed to keeping them there until a stable government is formed -- Kerry is hamstrung, both politically and on a policy level, from reaching out to those voters by making an unequivocal stand on Iraq.

Kerry didn't have that problem 33 years ago this month, when he sat down before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and asked, "How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?" CNN's Judy Woodruff put the same question to John Kerry Wednesday. He said a lot of words, but he didn't answer.

Shares