Last week, as the Bush administration struggled to contain the Abu Ghraib prison torture scandal, Peter Feaver, a Duke University professor and former National Security Council staff member, suggested a worst-case scenario for the White House: If "a senior civilian, or maybe even [Secretary of Defense] Rumsfeld, [had] signed a memo that indicated, yes, sexual humiliation for prisoners is OK."

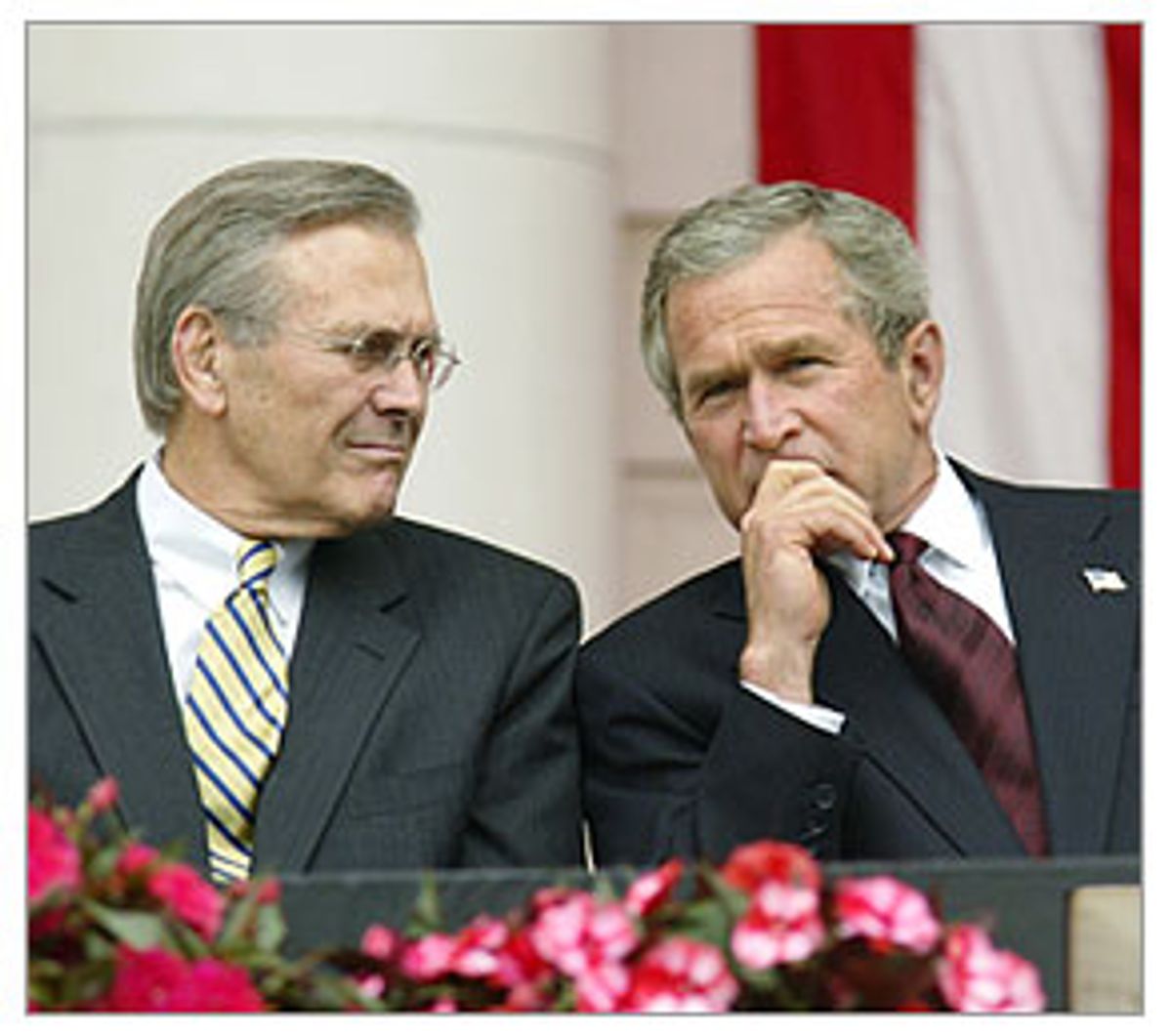

Now Seymour Hersh has summoned that worst-case scenario to life with an article in the May 24 issue of the New Yorker, providing evidence alleging that Rumsfeld secretly approved a plan to use harsh interrogation methods on prisoners in Iraq -- including methods that "encouraged physical coercion and sexual humiliation of Iraqi prisoners." The Pentagon labeled the article "outlandish, conspiratorial and filled with error and anonymous conjecture," but it did not specify the errors and had the sound of a classic nondenial denial. Rumsfeld's attempt to dismiss the piece did not forestall bipartisan calls in Congress for further investigation, with Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich., the ranking member of the Armed Services Committee, declaring that Hersh's article raises the scandal to "a whole new level."

At the same time, Newsweek reports this week that in the wake of 9/11, White House counsel Alberto Gonzales advised President Bush that the Geneva Convention articles that deal with interrogating prisoners of war might not apply to the war on terrorism. Newsweek's revelation suggests that Gonzales' memo may have established a foundation for the torture that followed.

For weeks the Pentagon has suggested that the prison abuse cases arose from too little oversight at Abu Ghraib. That was clearly the finding of Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba, who investigated the abuse allegations for the Army. But what if the opposite were true and those overseeing Abu Ghraib initiated the unlawful treatment? The more that is exposed, the more the Abu Ghraib scandal looks less like a case of renegade soldiers. How high up the chain of command does it go?

"That's the question -- was the abuse a result of the absences of command guidance or the result of command guidance?" says John Pike, an intelligence expert and the director of GlobalSecurity.org.

"You can busy yourself going through the military chain of command and looking at the actions of the [Abu Ghraib] guards," says Rep. Ellen Tauscher, D-Calif., a member of the House Armed Services Committee, who thinks the scandal's focus should be on top civilian leaders. "But the truth is, they were taking orders and the orders came from the Pentagon, which has complete and unfettered control of the war effort. There was a change in policy [at the prison]. Something caused people to vary from what was right and to 'amp it up,' and this is what you get."

For Tauscher, the scandal is a case of déjà vu. In 2002 and 2003, during the feverish run-up to war with Iraq, the civilian leadership at the Pentagon, frustrated with the analysis it was receiving from the CIA about the level of threat posed by Saddam Hussein, took the extraordinary step of setting up a secretive, in-house intelligence shop, staffed by handpicked hawks, to help maneuver stories that Iraq was an imminent "weapons of mass destruction"-level threat around the normal intelligence-vetting process. That effort was a success in providing the impetus that the Bush administration used to drive the country into war, but those stories have since been revealed as disinformation, much of it originating with neoconservative favorite Ahmed Chalabi, the Iraqi who boasted about being a "hero in error."

Fast-forward to the summer of 2003. Frustrated with the lack of good intelligence about the absent WMDs and the simmering internal Iraqi resistance, the civilian leadership at the Pentagon reportedly took the extraordinary step of allowing Iraq's largest prison, Abu Ghraib, to be put under the command of military intelligence instead of the military police. The idea was to turn the detention center into an intelligence-gathering outfit and, contrary to longtime Army regulations, make M.P.'s an integral part of the interrogation process to "soften up" the prisoners.

"Do you see a pattern?" asks Tauscher, who raised concerns last year about the administration's top-down pressure to produce a certain kind of war intelligence. It was the same type of pressure that led Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, who oversees the U.S. fighting force in Iraq, to hand over authority of Abu Ghraib to the 205th Military Intelligence Brigade last Nov. 19. Then, Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Miller, who at the time was running Camp X-Ray at Guantànamo Bay, where prisoners are detained indefinitely as unlawful "enemy combatants" outside the Geneva Convention, gave orders to "Gitmo-ize" the prison.

"Miller was sent to turn Abu Ghraib into an intelligence production center rather than a detention facility, and that's where the Geneva Convention stuff starts to get in the way of winning the war," Pike says. The obvious differences between the two prisons -- X-Ray holds those thought to have ties to al-Qaida -- seem to have been overlooked in an effort to uncover better intelligence. The International Red Cross, in fact, has reported that 70 to 90 percent of the prisoners at Abu Ghraib have been imprisoned there by mistake, simply rounded up in dragnets.

"The White House was frustrated by the lack of information being obtained from detainees and was screaming for intelligence about WMDs and insurgent leaders," says Vince Cannistraro, a former CIA counterterrorism chief. "Commanders were under pressure from Washington, and that translated into taking off the gloves."

One key to the debate about who bears ultimate responsibility centers on the mystery of authority at Abu Ghraib. If it's true that a group of rogue M.P.'s ran wild inside the prison, then the chain of command would likely go up to Brig. Gen. Janice Karpinski, who was in charge of all the prison operations in Iraq, and the scandal would essentially remain contained within the Army.

But if military intelligence officers, perhaps acting according to Rumsfeld's secret orders, are to blame for the abuses, or if last November's fateful decision to amp up the intelligence-gathering efforts is a significant factor in the debacle, than the spotlight will likely bypass Karpinski and her M.P.'s and start climbing up the chain of command.

"If it's military intelligence and you go up the chain of command, you get to the Pentagon and to [Stephen] Cambone and Rumsfeld," explains Cannistraro. In Cambone's testimony before Congress last week, the undersecretary of defense for intelligence contradicted Taguba's assertion that military intelligence had control of Abu Ghraib. Cambone's version, which evoked skepticism from some members of the Senate Armed Services Committee, was that military intelligence was acting as a sort of building supervisor, taking care of the prison grounds while the M.P.'s maintained control of the prisoners.

"Cambone is trying to create a firewall around the top chain of command," says Greg Thielmann, who ran military assessments at the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research until he retired last October. "If guards were following military intelligence and [ranking M.I. officer] Col. Thomas Pappas, then who was he reporting to? Ultimately you get to Cambone -- and that firewall is not going to hold. One way or another, these guys above the identified culprits [running the prison] are in big trouble."

"I think it will go to Cambone," says retired U.S. Army Col. David Hackworth. "The original game plan was to fry a few fish: sergeants and corporals. Then they decided [they'd] have to fry some bigger fish: Pappas and Karpinksi. That won't work because they'll blow the whistle [on] Cambone, who's the ultimate boss of intelligence and a micromanager."

Cambone does not deny that last summer he encouraged Miller and a team of 30 specialists to travel to Abu Ghraib in hopes of improving the prison's intelligence gathering. But Cambone testified that Miller was not sent to Iraq with official directives, that he himself did not encourage M.P.'s to become involved in interrogation and that when Miller subsequently recommended breaking down the wall between military intelligence and the M.P.'s at Abu Ghraib, he never briefed Cambone about it. (Cambone also told senators that he did not read the Taguba report and was unaware of the abuse photos until after CBS's "60 Minutes II" broke the story about prison abuse on April 28.)

Sen. Hillary Clinton, D-N.Y., spelled out the potential trouble for Rumsfeld and the White House: "I, for one, don't believe I yet have adequate information from Mr. Cambone in the Defense Department as to exactly what Gen. Miller's orders were, [and] what kind of reports came back up the chain of command as to how he carried out those orders."

Sen. Jack Reed, D-R.I., was equally skeptical of Cambone's testimony: "Gen. Miller suggested that guard forces be used to set the conditions [at Abu Ghraib]. Yet you did not choose to ask about this. You were completely oblivious."

During the court-martial proceedings for Abu Ghraib guards scheduled to begin later in the week, the exact role of military intelligence will get further scrutiny. Unsurprisingly, the debate at the center of the legal jockeying is about who controlled Abu Ghraib -- military intelligence or the military police. According to the statement he gave to investigators last January, Army Reservist Jeremy Sivits, who struck a plea-bargain agreement with the government and has agreed to testify against his fellow soldiers, acts of random violence were perpetrated on prisoners. He insists they did not come down as orders from above but were carried out by low-ranking personnel like Spc. Charles Graner, who reportedly punched prisoners unconscious, hit wounded detainees with baseball bats, and posed for photographs atop a pile of detainees.

But last week, Graner's attorney pointed a finger at military intelligence officers and private contractors as the ones who barked orders to M.P.'s, who were simply following those orders. Graner's attorney suggested that Sivits is implicating low-ranking soldiers as part of his plea agreement.

The part played by the private contractors at Abu Ghraib remains a mystery, as does their possible punishment. Under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, "persons serving with or accompanying an armed force in the field" are subject to the code "in time of war." That might cover the contractors, whose actions captured in photographs clearly violated the code. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces previously held that the military lacked jurisdiction over civilian employees of the Armed Forces during the Vietnam War because, the court ruled, the phrase "in time of war" contained in the code meant a war formally declared by Congress. The Vietnam War was never formally declared by Congress. Nor was the invasion of Iraq.

The unfolding investigations could take two parallel tracks. At some point soon the scandal will reach a decisive moment and either halt at the low-ranking M.P.'s or go up the chain.

For now, the White House finds itself losing allies among Republican senators as the bipartisan calls for further investigations continue. The administration cannot find support inside the military, either. "For military officers, this scandal is outrageously infuriating; it has tarnished everybody," says Ralph Peters, a retired Army intelligence officer and regular contributor to the reliably conservative New York Post editorial page. "The civilian side at the Pentagon, like Cambone -- they were the ones trying to cover this up, not the military. I believe Donald Rumsfeld needs to go because he has lost the trust and respect of the officer corps."

Shares