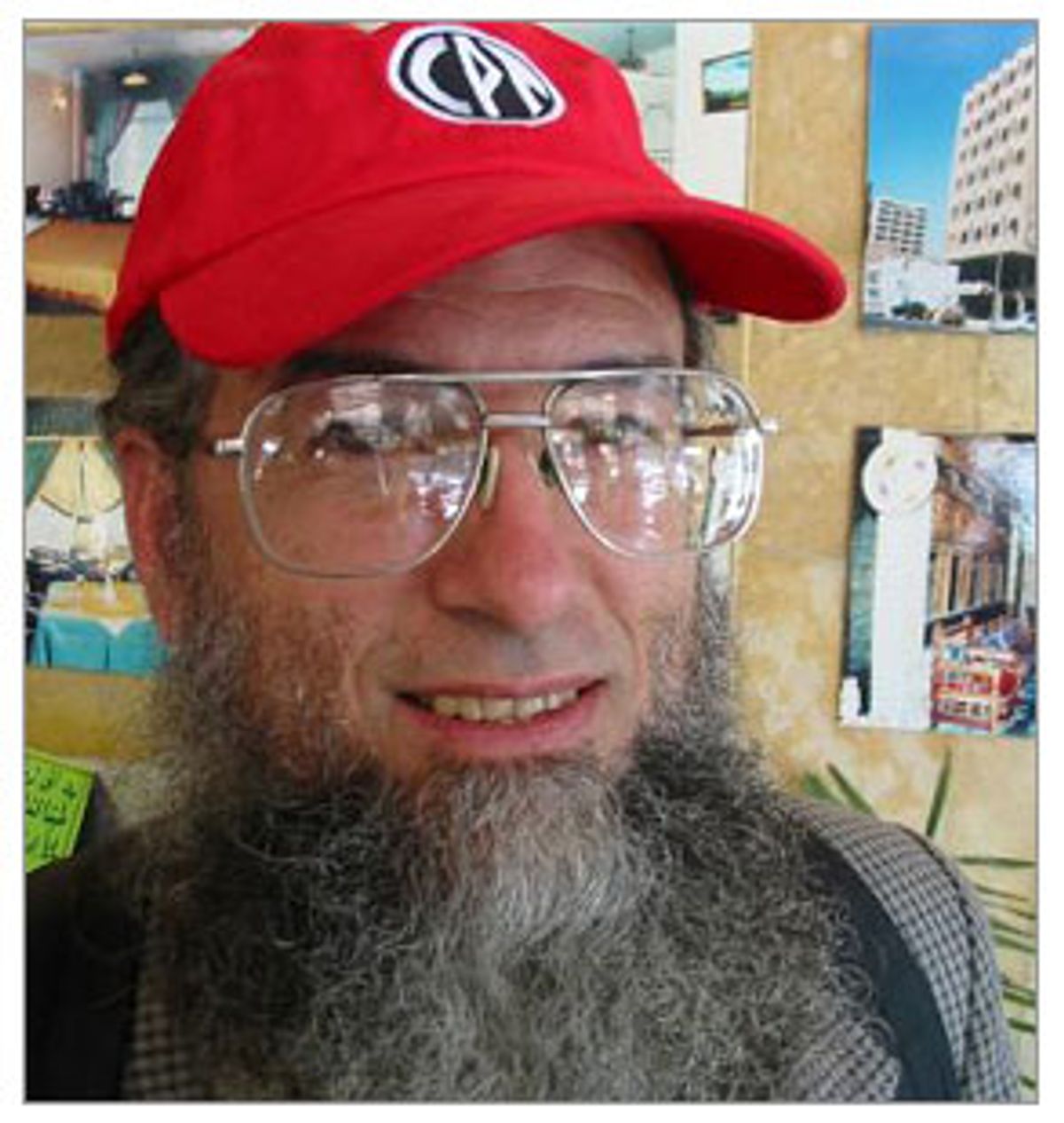

For much of the last year Cliff Kindy, an organic-vegetable farmer from Indiana, spent his days in the war-torn terrain of Iraq, documenting human rights abuses for the U.S.-based religious activist group Christian Peacemaker Teams. His work there started long before the Abu Ghraib torture scandal shocked the world -- and it was a daunting task to convince American reporters that Iraq had a human rights problem.

"We were always trying to get U.S. press," he says. "It was like we were invisible."

Since the Abu Ghraib story broke in late April, the organization's work -- primarily taking firsthand testimonials from Iraqis, many of them quite disturbing if difficult to verify -- has been cited in major media including the New York Times and the New Yorker magazine.

Fifteen years ago Kindy, a devout Methodist, helped found Christian Peacemaker Teams, whose motto is "Getting in the way." His first mission as a human rights observer was to refugee camps in the Gaza Strip in 1994.

In the fall of 2002, Kindy and some of his fellow activists went to Baghdad in the hope that a presence of American pacifists might help halt the march to war. After President Bush declared an end to major combat operations in May 2003, CPT activists in Iraq shifted their focus from trying to stop the war to documenting life under the American-led occupation. Kindy says they've since collected over 200 accounts alleging abuses by the U.S. military, which they hope will garner media attention, fuel a letter-writing campaign by sympathetic church groups and help in lobbying U.S. policymakers.

But convincing occupation officials to soften their military tactics and detention procedures has been an uphill battle, particularly in the face of mounting American casualties. U.S. Army Lt. Col. Nate Sassaman, with whom Kindy had several personal encounters, spoke frequently about his efforts to win "hearts and minds" through simple acts like helping bake bread in a villager's home. Sassaman was a battalion commander who oversaw operations around Abu Hishma village among other areas in the notorious Sunni Triangle. As pockets of Iraqi resistance began to flare up late last year, Sassaman's relations with Iraqis became markedly different. He became infamous last November for enclosing the entire village of Abu Hishma in razor wire after an attack on one of his convoys occurred nearby. "If our base gets attacked," Kindy remembers him saying, "we open up in every direction."

Despite having heard numerous harrowing stories from released Iraqi prisoners, Kindy was still caught by surprise by the brutality exposed at Abu Ghraib. "Detainees were saying that the worst times were in the intake stages. The assumption was that when they were in temporary facilities or U.S. military bases scattered across Iraq they were more likely to be tortured," he says. "We thought that once they got to the permanent facilities, like Buca camp down in the south or in Abu Ghraib prison, that things improved because there was a routine in place."

Kindy returned to the United States in March from his second five-month mission in Iraq with Christian Peacemaker Teams. He spoke with Salon by phone from his farm in Indiana on Wednesday.

Once the war started, the role of Christian Peacemakers changed. How did your organization get into interviewing Iraqi detainees?

Right after the war, we were trying to find our way. It was in that period we were looking at unexploded ordnance, the danger of that for children and communities. We were also a presence with some of the nonviolent demonstrations.

But then this whole detainee issue started to open up. Neighbors and acquaintances started to come to us and say, "We don't know whether our detainee is alive, what the charges are, where they're being held. Can you help us?" Because we spoke English like the soldiers, sometimes we could facilitate answers. That developed through the fall, and we began hearing more and more stories. That led to a report that we wrote toward the end of December last year that carries some of the details of our findings working with about 70 detainee cases. And that continued as we worked our way up the civilian and military ladders of the occupation [with our findings] at the request of a couple of U.S. army officers.

U.S. Army officers asked you to inform their superior officers that abuses were taking place?

We shared our report with a staff sergeant at the Iraq Assistance Center. He passed it on to a couple of other people -- a Maj. Simmie Clincy and a Col. Fisher -- and they came to one of the meetings. At that meeting, on Dec. 22 last year, they said they didn't agree with everything, but they acknowledged to us, "We're giving orders out in the field to our soldiers that are putting them at long-term risk in order to have short-term security. We need to have policies developed to change that."

So the Army officers had told you that they were receiving orders on how to deal with Iraqis that they considered improper or inhumane?

Right. But they said that in the chain of command they couldn't reach the people who make the policies. They set out the steps we'd have to take to work our way up to the top in the U.S. occupation authority. Eventually we met with Ambassador Richard Jones in Civilian Administrator Paul Bremer's office. Jones, who was former ambassador to Kuwait and Lebanon, had been brought in in early December to fix the problems with the detainees. We also met in Gen. Ricardo Sanchez's office with Col. Mark Warren, the highest-ranking legal officer for the U.S. military in Iraq.

Col. Mark Warren has been in the news recently denying that torture was part of the military's interrogation policy. What went on in your meeting with him?

It was Feb. 14, a Saturday. Warren had been in Baghdad since April 2003. I remember him saying, "We try to comply with the laws of war and human rights law," and that "we try to have our soldiers be culturally aware. We're putting out a new [order] to be precise about how much force needs to be used, and to be restrained in that." Warren also said there would "be dramatic improvements in the next few weeks."

He also mentioned the movie "The Battle of Algiers." He said, "[Brutal tactics] worked in the short term, but they blew up in the face of the French. If they had worked, Algeria would be French now." He said that was something "we need to learn from."

He seemed to be trying to say that the U.S. wouldn't use these kind of extreme interrogation tactics -- that they wouldn't work. The Abu Ghraib story hadn't blown at that point. "We're bringing a new group of MP's to Abu Ghraib," Warren said, "that are oriented to do family visits." I don't know if they're the ones who also did the interrogations.

You also had some personal interactions with Lt. Col. Sassaman, who, according to the Washington Post on April 5, was "disciplined for impeding [a] probe" into an incident where American soldiers allegedly forced two Iraqis to jump off of a bridge. What was it like working with him?

Sassaman is an interesting character. He was the one, because of an attack on one of his convoys near Abu Hishma village [in November of 2003], who encircled the village with five miles of razor wire and instituted a nightly curfew. We also heard reports where, in raids on Abu Hishma, Sassaman's unit took relatives hostage in order to get other people.

It was collective punishment. Even if people from the village did attack that convoy -- and that wasn't clear -- you can't justify punishing the thousands of people that lived in that village for the actions of a few people.

I think part of his response was out of his frustration at having soldiers injured or killed. It was also at those times that we'd hear about some of the more serious allegations going on under his command. He said that when they're not clear where an attack comes from, they just let loose with everything. I remember him saying, "If our base gets attacked, we open up in every direction."

What was CPT's reaction when the images from Abu Ghraib started appearing in the media in late April?

Well, it kind of blew us away -- not because we hadn't been aware things like that were occurring, but because from the testimonies we had taken, detainees were saying that the worst times were in the intake stages. The assumption was that when they were in temporary facilities or U.S. military bases scattered across Iraq they were more likely to be tortured, they were more likely not to be protected from the weather, that they were more likely not to have sufficient water or food. We thought that once they got to the permanent facilites, like Buca camp down in the south or in Abu Ghraib prison, that things improved because there was a routine in place. When this story broke, we realized it was much bigger.

We'd been hearing some stuff from Abu Ghraib, but it wasn't as significant as those early intake stages. We'd heard reports from Abu Ghraib village outside of the prison, saying that the women inside were asking that the prison be bombed, destroyed, because what was happening inside was too terrible to live with. We were hearing some reports of torture inside the prison, fingernails, thumbnails being pulled off, but not the kinds of [sexual] abuses we've heard about in the last few weeks.

CPT is one of the few human rights organizations that publishes first-person testimonials. Why do you use that approach?

A lot of that is for our constituency, so they can write and bring pressure to bear on government officials. It's a way to make the story more personal for them; it grabs their interest more quickly; that's one of the reasons we use it. Also, we're hoping that emphasizes less of our own perspective in the story.

But doesn't that make you less of an objective fact-finder than someone who's there to air Iraqi grievances?

What we say when we take testimony is not that we have necessarily verified the accuracy of it. What we are saying is, "This is what a detainee or a family came and told us about their situation and experience."

We aren't lawyers. We don't pretend to have a fully balanced story. But we have had experiences in lots of different communities that seemed to be consistent.

And we don't put everything we hear in our longer reports. We try to be critical about what we put in; if we weren't sure about a story, we'd leave it out. If it sounded like exaggeration and we weren't getting any confirmation of it from other places, we'd usually let it go.

At one point we were led to understand that probably the Sunni Triangle would be worse, because that was where resistance was happening. Well, we got outside the Sunni Triangle frequently and the stories were coming down in Kerbala and Najaf, as well, and up in Dialah. It seemed clear that the abuses weren't just a "geographical problem" with the occupation.

It's not that there's a handful of people upset with the occupation. Most Iraqis are upset with the occupation. They don't need anybody to tell them what's wrong with the occupation because they can see it, they've experienced it, their family members have experienced it.

Several testimonials published by CPT contain some extreme allegations. Do you think that some of the stories you heard were embellished?

There were a few of those kinds of stories, yes. But for the most part, I think the stories included in our cumulative report follow a familiar pattern. Humiliation, lack of cultural sensitivity on the part of U.S. soldiers, lack of accountability. Soldiers were not held accountable for actions.

Do you think other human rights organizations working in Iraq have been more conservative in reporting suspected instances of abuse?

Maybe in the sense that they don't have a very clear picture of what's happening across Iraq. I'd expect that a group like Care, or the American Friends Service Committee would be more cautions about what they said about this issue because they haven't been so much involved in it. The kind of experiences we've had, the things we've seen and taken testimony about, give us a little more of a base to speak with boldness and credibility.

Did you ever personally witness abuse of Iraqis while you were there?

We weren't present when serious abuse was happening against Iraqis. I'd see people being humiliated at a checkpoint, that kind of stuff. But nothing like dogs or electrical prods used on them. Most of the time, I think "the grandma factor" is at work: People don't like others to see them doing bad things. It's one of the strengths of the Christian Peacemaker Team presence.

How did the American media respond to the CPT's reports of abuse before the Abu Ghraib story broke?

We were always trying to get U.S. press. It was like we were invisible. We decided we needed to make a concerted effort to build relationships with these press people. So we started visiting them, and we talked about Abu Siffa [a village on the Tigris where CPT had extensively documented the use of harsh tactics by U.S. forces]. And Jeff Gettleman, a reporter for the New York Times, called us at one point, so two of our group went up to Abu Siffa with him. They talked with Lt. Col. Nate Sassaman, the commanding officer for troops in the area, and talked with people in the village, and wrote the story for the front page of the New York Times. I think it was a miracle that we got that to happen.

Can you describe the relationship between CPT and the U.S. military?

Our meetings with higher officials and officers are fairly congenial. We usually start with trust, we assume that people we meet are going to be friends, and I think in general that's what we've found in those meetings.

But it's mixed. I'd pass out our human-rights leaflet to a couple of soldiers on the street, and one guy's ready to ball it up and throw it back in my face, while another one says, "Oh, give me some more information, do you have any Web sites on this, do you have a G.I. rights hotline I can get in touch with?"

In general I think that U.S. soldiers are happy to meet somebody who speaks English -- reminds them of home, someone who's willing to listen to them.

Religious faith is a prominent aspect of CPT's outlook. How does that affect your work?

Every time I go into a conflict zone I am emotionally impacted by the experience, sometimes traumatized, and if this work is going to be sustainable, we need to find the tools that enable us to return somewhat healed. It helps me focus, see the bigger picture and issues like forgiveness, justice, love, nonviolence. Those for me come out of my Christian perspective, although they're not unique to a Christian perspective. We've worked very closely with Muslims, with Jews, and we've learned and been strengthened from those experiences. For us, though, this is what brings us to this work.

We've had very close connections with some leading Sh'ia and Sunni clerics in Baghdad. And maybe it's because they see us as people of faith as well. I think that common commitment to faith has opened doors we wouldn't have open if we were secular peacemakers. I think that's key.

Which clerics did you have a relationship with?

We've worked with Sheik Moayyad [Ibrahim al-Aadhami] at the Abu Hanifa Mosque in the Adamya district, and Sayyid Ali [Mussawi al Waahd], the overseer at the Kadim shrine. We met regularly with them, especially with Sheik Moayyad, because we were working with detainees and we would often take delegations to his mosque.

With Sayyid Ali we were there for Ashura [a Shiite religious festival banned under Saddam Hussein; 180 people were reported killed by suicide bombers during the festival on March 2, 2004]. Half our team was there with Sayyid Ali when the big explosions happened in the mall in front of the shrine. It was pretty horrendous.

How did you work with these religious leaders on human rights issues under the occupation?

Let me talk about Sheik Moayyad. Sheik Moayyad spent eight years in prison under Saddam. When he was released, he came back to lead the Abu Hanifa mosque.

He said that one day an Apache helicopter opened up on a minaret, there was an attack in the area of the mosque, and about 45 people were killed. He talked about going outside the front to see dozens of tanks and Humvees right outside his mosque. He asked me, "When will we learn to talk with people about our differences? When will we learn to resolve our differences as human beings even though we are on different sides of an issue, rather than shooting at each other?" He's one of the people that gives me hope that things can change over there.

We've regularly gone to Sheik Moayyad for help documenting detainee abuse. He's given us names, we've worked with those detainees, heard the stories from the prisons, from the intake detention facilities used by the military. He knows many of the people personally, and he tells us, "This person I can't vouch for, but these people I can vouch for. The charges against them are false." He'd make suggestions, who we should talk to, and somebody from the mosque would usually take us to the house, or they'd bring the person to the mosque and we'd interview them there. Because of Sheik Moayyad, we had those connections, and built personal relationships with people.

Sayyid Ali, I don't think we had any detainee cases from his community. But because he's in charge of the biggest Shia mosque in Baghdad, and is close to Ayatollah al-Sistani, he'd probably say it's time for the occupation to end. He's been patient so far with the occupation, but the United States needs to let Iraqi political leadership make the decisions to shape the future. Whether the U.S. military presence can continue, when the elections should take place -- he believes those should be decisions made by Iraqis, not by U.S. appointees. He would be considered a moderate Shiite, but even the moderates are losing their patience at this point.

What do you hope CPT's work will accomplish?

Accountability. And I hope it opens up a new way for us to understand those categorized as our "enemy." We try to tell the story of people on the other side of barriers, that can easily become dehumanized if we don't know them.

Also, I think our presence helps make it safer for U.S. soldiers. Because more Iraqis need to meet Americans who aren't carrying guns and don't ride in tanks.

Shares