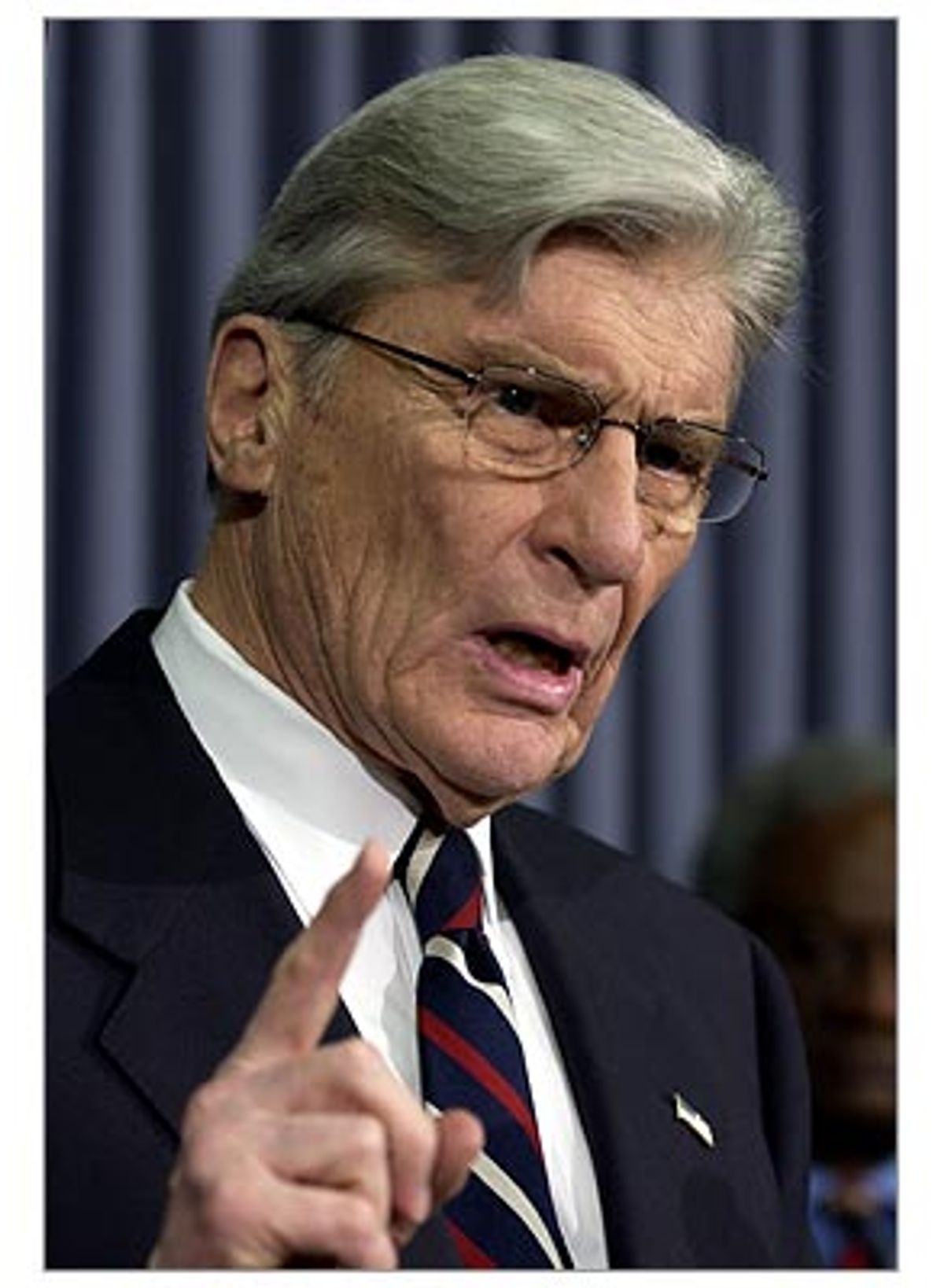

John Warner does not shout. Or pound the table with his fist. The chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee has -- in public, at least -- been patient and polite in his questioning of administration witnesses about the Abu Ghraib prison scandal, maintaining the formality and decorum he values in public life. Behind closed doors, however, the Virginian has surprised observers with occasional flashes of anger at Donald Rumsfeld's evasions, according to people who have attended private committee meetings with the defense secretary. "He gets a stern look, and becomes real quiet. He doesn't say anything, but it's obvious when he feels he is getting anything less than candor," one of those present said of Warner.

Warner, some of his Senate colleagues told me, will not be cowed into halting the politically wrenching hearings on prison abuse. He is motivated by a strong sense of duty to get to the bottom of a scandal that has deeply scarred American credibility in the world and contributed to growing disapproval among voters of President Bush's handling of Iraq.

Through a spokesman, Warner declined to be interviewed for this story. But at a hearing last month, he called the prison abuses "as serious an issue of military misconduct as I have ever observed" and "an appalling and totally unacceptable breach" of military standards.

While some of his more outspoken colleagues on the Armed Services panel can be flashy bling-bling, capturing the sound bites, Warner's style is more like a strand of pearls: elegant, polished and deceptively tough. The Navy and Marine Corps veteran doesn't pick many fights, but when he does, it's for what he considers strong principles. Which is why the five-term Republican is potentially more threatening to Bush's effort to tamp down the public outcry over Abu Ghraib -- and to his reelection -- than all of the Democrats on Capitol Hill combined.

What should be most worrisome to Bush, perhaps, is that the last time Warner took on something this big -- a showdown with conservatives in Virginia over the Senate candidacy of Iran-Contra figure Oliver North, darling of the right wing -- he won decisively. "He wants to get out the truth," said Sen. Jack Reed, D-R.I., a former Army ranger and paratrooper who has been one of the leading critics of the administration on the Armed Services panel. "He knows that if we're going to stand in the world for the rule of law, we're going to have to ourselves stand for the rule of law."

With Congress returning to Washington this week from its Memorial Day recess, the Armed Services Committee is expected to schedule new hearings soon on an investigation by Major Gen. George Fay, the Army's deputy chief of staff for intelligence, into whether military intelligence officers directed the sexual abuse and torture of Abu Ghraib prisoners. Reed and other committee members fear a Pentagon coverup, questioning whether Fay can credibly investigate his own intelligence operation.

Newsweek reported this week that Fay failed to interview senior officers to determine how high in the chain of command responsibility lies. A sergeant assigned to military intelligence at Abu Ghraib told the magazine that Fay's interview with him was decidedly unenthusiastic. "I had to volunteer more information than was being asked of me. It was like I was adding to his burden," Sgt. Samuel Provance said. "There are so many soldiers directly involved who haven't been talked to."

The hearings on the Fay report will mark a second round of political bloodletting for the administration. Last month Warner hauled Rumsfeld, Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence Stephen Cambone, Iraq commander Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez and U.S. Central Command chief Gen. John Abizaid to Capitol Hill for public hearings. In a sign of his seriousness, Warner insisted that Rumsfeld testify under oath, declining to grant the secretary the usual courtesy of appearing under more informal circumstances.

Last month's hearings, predictably, infuriated conservatives. House Armed Services Committee chairman Duncan Hunter, R-Calif., criticized his Senate counterpart for pulling Sanchez, Abizaid and other commanders away from pressing duties in Iraq, though the officers were already in Washington for a previously scheduled visit. And Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Okla., said he was "outraged by the outrage" over Abu Ghraib, blaming "humanitarian do-gooders" for kicking up an unnecessary fuss.

One observer doubts that the barbs of conservatives bother the 77-year-old Warner, Virginia's most popular politician. "Pesky little flies. Swat them. I'm sure that's the way he looks at these guys," said Mark Rozell, chairman of the department of politics at Catholic University in Washington.

Speculation that Warner is attempting to shuffle Rumsfeld out the door, however, is probably going too far, his colleagues say. Warner fueled such talk last month when he told reporters that Rumsfeld's resignation is "a subjective decision that only he can make." Yet Warner has expressed no preference to Armed Services Committee members about Rumsfeld's future, and few believe he would try to push out the secretary, in deference to the president's prerogative to choose his own Cabinet. Still, Warner is caught in a bind between loyalty to a Republican president and his duty to the country. He supported Bush on waging the Iraq war. Yet he also believes strongly that Congress has a constitutional obligation to oversee the executive branch, colleagues say. Then there's the issue of his conscience. "I'm sure he was offended to the bone by the pictures of the recent incidents," said retired Marine Corps Col. John E. Greenwood, a former aide to Warner.

The son of a World War I field surgeon, Warner was born in Washington and enlisted in the Navy in January 1945, at age 17. He served through the end of World War II, then attended Virginia's Washington and Lee University, from which his father had graduated in 1903. After completing a degree in engineering, he entered University of Virginia Law School, temporarily interrupting his studies to join the Marine Corps when the Korean War broke out in 1950. He then spent 16 years as a judge's clerk, an assistant U.S. attorney and a lawyer in private practice before President Nixon appointed him undersecretary of the Navy in 1969. Three years later, Nixon promoted Warner to secretary of the Navy.

Warner's aides from that time, during the Vietnam War, remember little about the war issues he handled. What they do recall vividly is Warner the personality: his stylish European suits; his marriage to one of the country's wealthiest women, banking heir Catherine Mellon; and his commanding yet nurturing manner.

Tom Marfiak, a Navy lieutenant who served as Warner's special assistant, recalls attending a high-level meeting one day. Awestruck by all the four-star generals and admirals there, Marfiak said, he ended up sitting on his sleeves to hide his low-ranking two bars. Warner barked, "Marfiak! Are you sitting on your sleeves?" He replied that he was. "Well, put your arms up on the table where everyone can see them," Warner told him. "You may be a lieutenant, but you're my lieutenant."

Warner had great respect for rules and tradition, but he was also a pragmatist who would defy the playbook when his judgment told him better. In 1972, he extended the term of naval operations chief Adm. Elmo Zumwalt Jr., who was roiling the service with his aggressive racial integration programs. "He realized, as Zumwalt did, that the Navy needed to change," Marfiak said of Warner. "So he linked elbows with Adm. Zumwalt and said, 'We've got to go fix this.' And fix it they did."

Greenwood, who worked for Warner at the Department of Defense for five years, recalled that his boss had once been asked to sack a warrant officer who'd been caught in a three-way sexual encounter with a married couple. Navy rules required the warrant officer's dismissal, but Warner considered the man's consensual sexual relations with adults a private matter that had no bearing on his public duties. "He wasn't afraid to make an exception to the rule," Greenwood said. "The incident had no impact on the Navy, nor was it a public scandal. But if Warner had gone solely by the book, it would have been like sentencing some kid to 10 years in prison when the most he needed was a whipping."

Also toiling away for Secretary Warner in the early 1970s was a young Navy officer named John Poindexter. A computer expert, Poindexter had devised a new electronic tracking system for correspondence that was revolutionizing the secretary's office. He was quiet and hardworking, and Warner -- as with everybody -- appeared to get along splendidly with him, other former aides said. Poindexter and Warner parted ways in 1974, when Warner left the secretary's job amid the aftershocks of Watergate. But they would meet again.

By then, Warner's marriage to Mellon had ended, but the parting was amicable, no doubt smoothed by a $3 million divorce settlement for Warner. In 1976, Warner married actor Elizabeth Taylor. Two years later, he lost the Republican nomination for the U.S. Senate to conservative activist Richard Obenshain. When Obenshain died in a plane crash, leaders of Virginia's Republican Party reluctantly turned to Warner in the general election, expecting that in return he would adhere to conservative orthodoxy. But Warner would frequently disappoint them on such core issues as abortion, taxes and gun control.

Pumping money from his first divorce settlement into his campaign, Warner eked out a narrow victory over a lackluster Democratic opponent. Expectations were low. "Doonesbury" cartoonist Garry Trudeau ridiculed Warner in a strip as "some dim dilettante who managed to buy, marry and luck his way into the Senate," and a Pat Oliphant cartoon in the old Washington Star showed Warner, who owned a farm in Virginia's hunt country, riding the "thoroughbred" Taylor to victory.

But Warner proved adept at politics. As Hillary Clinton did in 2001, Warner initially kept his head down in the Senate, fearing his celebrity would prove a liability. He worked hard to build bridges with his Virginia congressional colleagues of both parties, and he and Taylor stayed off the party circuit and away from the paparazzi.

The worst fears of conservatives who believed Warner owed his seat to them were confirmed in 1987, when Warner voted against Robert Bork's nomination to the Supreme Court. But voters -- especially in the more urbane Virginia suburbs of Washington -- were increasingly pleased with the senator; Warner won reelection in 1984 with 70 percent of the vote and in 1990 with 81 percent. In 1993, he angered conservatives again when he refused to endorse the candidacy of Christian conservative and home-schooling advocate Michael Farris for state lieutenant governor.

Warner's most devastating blow to Virginia conservatives came the following year, when he not only opposed but actively worked to defeat Republican Senate candidate Oliver North, who was challenging Democratic Sen. Charles Robb of Virginia. North and his former boss John Poindexter -- who had risen to become national security advisor to President Reagan -- were conservative heroes for their leading roles in the Iran-Contra affair, in which they illegally diverted the proceeds of secret arms sales to Iran to fund the anti-Communist Contras in Nicaragua. Warner found North's candidacy so repugnant that he pushed an independent candidate, Marshall Coleman, to run, and campaigned heavily for him. For Warner, who values conviviality and consensus, the clash with Poindexter, his erstwhile subordinate, was painful, but he was determined. North, in his view, was a liar who had tracked mud on the Constitution in pursuit of a rogue foreign policy. Indeed, Coleman drew enough Republican support from North to ensure Robb's reelection. Again, the voters were pleased: In 2002 Warner had no Democratic opponent and was reelected with 84 percent of the vote.

Nearly a decade after the showdown with North, Warner would clash once more with Poindexter. As Armed Services Committee chairman in 2003, he ordered an end to Poindexter's Total Information Awareness program, a massive terrorist-tracking database being developed for the Defense Department that critics called Big Brother in action. Warner, in his more understated way, labeled it simply an "egregious error of judgment."

It remains to be seen what impact the Armed Services hearings on Abu Ghraib will ultimately have. But the motivation of the panel's chairman, who has been involved with the armed forces in various capacities for 60 years, is clear. In a statement that could as easily have described his reasons for scuttling Marine Lt. Col. North's Senate bid, Warner kicked off the panel's hearings last month with a simple explanation for why the prison abuse must be thoroughly investigated. "It contradicts all the values we Americans learn," he said, adding: "This is not the way for anyone who wears the uniform of the United States of America to conduct themselves."

Shares