The Department of Homeland Security has started enforcing an obscure provision in immigration law requiring foreign journalists to seek special visas before entering the United States, even though their nonreporting countrymen can enter without any visa at all. Last year, at least 13 foreign journalists were detained and deported at U.S. airports -- most in Los Angeles -- according to the advocacy group Reporters Without Borders. At least one more journalist was similarly turned away this year after being detained, interrogated and strip-searched.

Why does the "land of the free" need to specially monitor and control the flow of incoming journalists? "Considering the fact that the United States has never licensed journalists, that in the United States anyone can be a journalist and that because most countries that require special visas for journalists tend to be totalitarian states, I think it's kind of stupid," said Lucy Dalglish, executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.

Under the Visa Waiver Program, citizens of 27 countries -- predominately from Western Europe -- can visit the U.S. for up to 90 days without first getting a visa. Among the questionable characters ineligible for visa waiver are convicted criminals, people with communicable diseases, suspected terrorists, slave traders -- and reporters. However, according to journalist advocacy groups, the law lay dormant until March 2003 when the Department of Homeland Security formally incorporated the Immigration and Naturalization Service and suddenly began enforcing it. (A spokesman for DHS said that while he could not cite specific cases, he did recall it having come up in the past.)

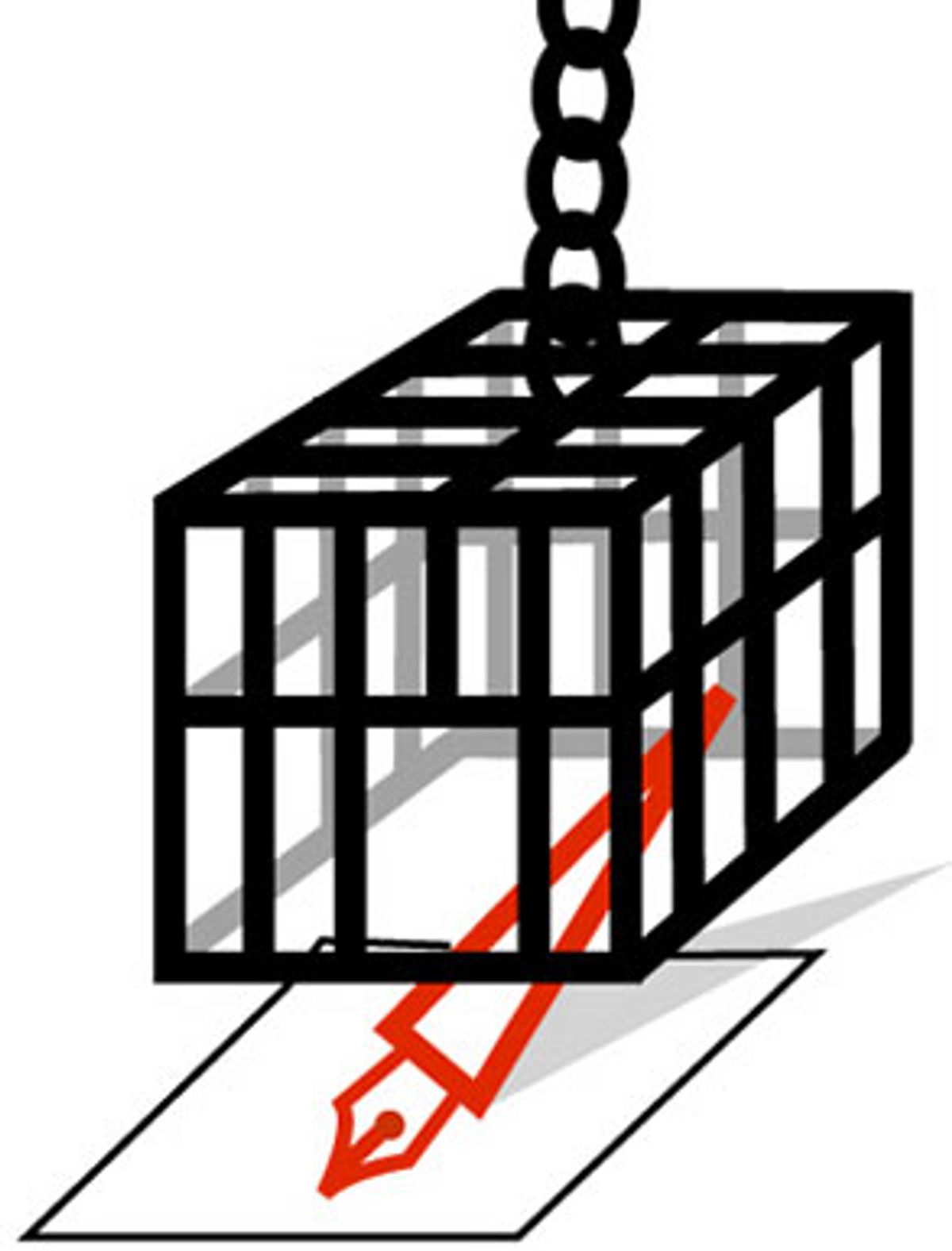

"It's really a slap in the face to the entire industry," said Kevin Goldberg, an attorney for the American Society of Newspaper Editors. "Not to mention the treatment of these people who have come here -- not just deported but really seized at the airport and violated at the airport. These are journalists, not terrorists, suspected terrorists. Their only weapon is their pen."

The most recent incident occurred in early May when Elena Lappin, a British freelance journalist traveling to Los Angeles to work on a story for the Guardian of London, was detained, questioned, strip-searched, handcuffed and taken to a downtown holding facility for the night. Twenty-six hours after arriving, she was put back on a plane to England. Instead of writing the article she planned, she gave the Guardian 2,400 words on her Kafkaesque encounter.

Lappin's case is not isolated. In 2003, 12 journalists were detained at and deported from LAX. Last March, a Danish photographer had DNA samples taken before he was deported. That same month, a Swedish reporter was turned away at a Washington airport, where he was photographed and fingerprinted, and not allowed to call his embassy. Last May, six French reporters in two groups were detained at LAX; they were on assignment to cover a video-game trade fair. All were deported, the first three "after being repeatedly questioned and body-searched six times," according to Reporters Without Borders. Similar fates awaited a Swedish freelancer in May, a pair of Dutch reporters that same month trying to cover an awards ceremony for world film stunt champions, a British reporter in October and an Austrian in December. In many of the cases, the reporters were treated like criminals: handcuffed and taken to prison holding facilities where some were not allowed to sleep.

According to Bill Strassberger, a spokesman for the Department of Homeland Security, detention and handcuffing of journalists is simply the product of following regulations. Once someone is rejected, the airline that brought them is required to return them, and in some cases flights are not available for 24 hours. "If they have to be transported to another location, then procedure requires that they be restrained," Strassberger said. "It's unfortunate because I know every time you hear about one of those things you cringe, but you do have that concern for officer safety."

Strassberger denied that the law requiring special journalist visas -- called "I visas" -- had lain dormant, but nevertheless acknowledged that it is being more vigorously enforced, because, he said, "quite honestly, 9/11. It goes back to after the terrorist attack, the inspections process, the inspectors, the customs and border protection officers are just being a little more thorough, a little more careful about who's coming in."

Reporters Without Borders, the American Society of Newspaper Editors, and the International Press Institute have all raised a hue and cry, which prompted U.S. Customs and Border Protection commissioner Robert C. Bonner to issue an advisory on May 20 allowing individual immigration officials to let "nonthreatening" reporters into the country without a visa -- once. "We are an open society and we want people to feel welcome here," Bonner said, apparently without any irony.

But as Goldberg, ASNE's lawyer, pointed out, the underlying problems remain unsolved. What happens if a foreign reporter who's had his or her one waiver needs to get into the U.S. to cover a breaking news event, like a real terrorist attack? "Another problem is that it opens the door to content review," Goldberg said. Added Dalglish: "Once you start putting an immigration officer at an airport in charge of who in the world is entitled to be a journalist and who isn't, that's on the path to defining who's an American journalist."

The other unanswered question is: Whose idea was it to crack down on the supposed menace of invading foreign media hordes. "The Bush administration doesn't like the press?" Goldberg asked rhetorically. "That's the best I can come up with, frankly. They've been reluctant for almost four years now to give information out to the press. They don't deal with the press on a level playing field. They've made life hard on other civil liberties. I can't imagine them bending over backward to help the press."

Shares