This is one of the ways the wounded come to the combat support hospital in Baghdad. At the U.S. air base in Taji, a dusty expanse 15 miles north of Baghdad, three tones come over the radio. When the four-man crew at the 421st Medevac Battalion gets this signal, they sprint toward their helicopter on the concrete pad. They run past the loaded Apaches and out to the Black Hawks parked under the crucible sun, their black hulls covered with big red crosses on white fields. There, the medevac crew waits by the helicopter for the arrival of an injured soldier. Once they have him, they will fly him to Baghdad for emergency surgery. It is a well-rehearsed routine and they do not say much as they work.

When the young American arrives on a gurney with the bullet wound in his abdomen, the medic lifts him into the helicopter, making sure he is lying on his left side to ease the strain on his heart. If the soldier, whose name is Chris, closes his eyes, the medic talks to him and wakes him up. Over the palm groves north of Baghdad, the medic works out an IV to keep him from going into shock, and watches the flow of saline into his vein. Eight minutes later, the crew is taking Chris off the Black Hawk and running with his gurney through the emergency-room doors of the combat support hospital. Dr. Sudip Bose and the staff of the emergency room are there waiting for him.

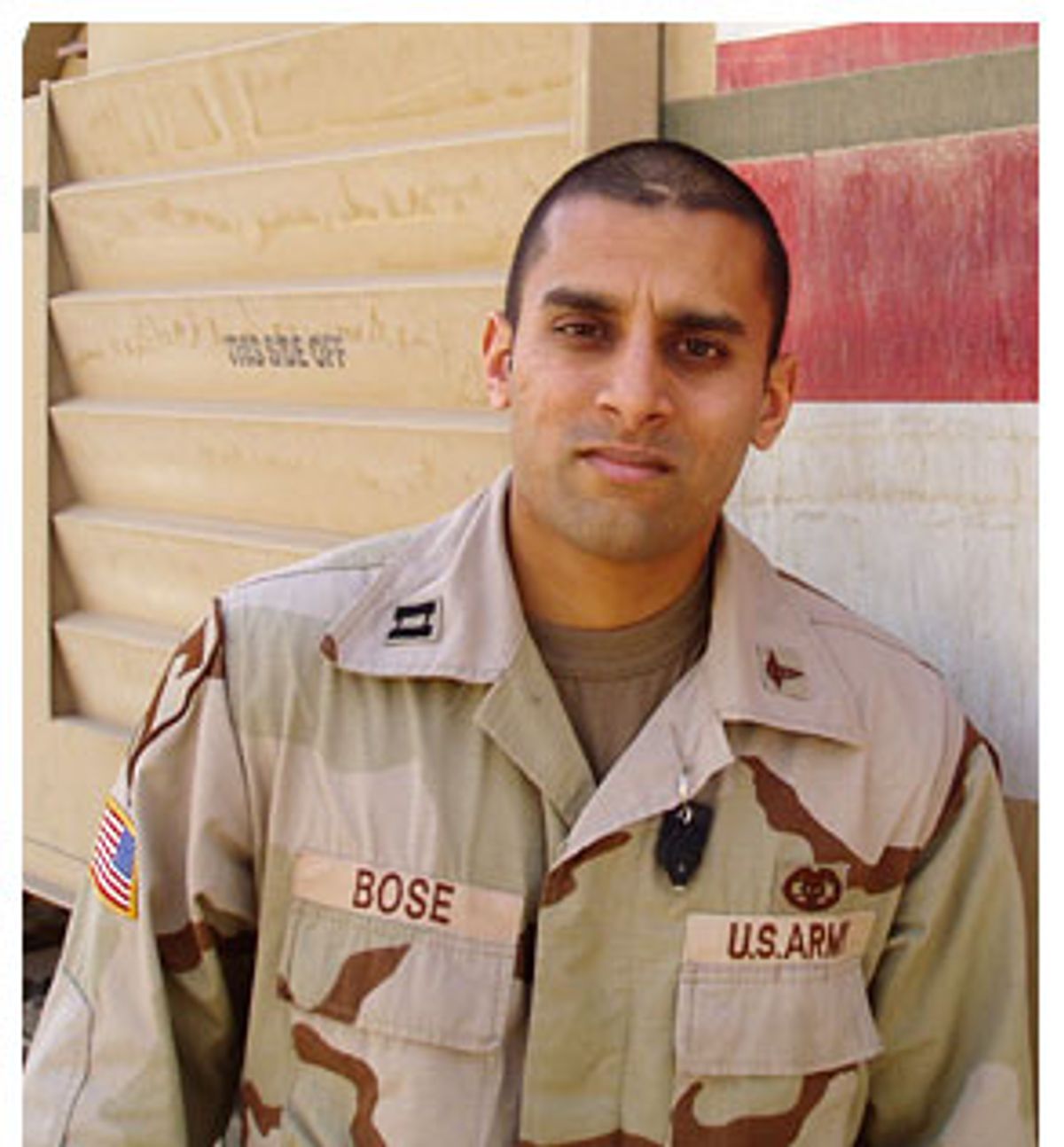

The injured soldier's doctor, Sudip Bose, is the lanky 30-year-old son of Indian immigrants from Calcutta. He grew up in Illinois and went to Northwestern Medical School, following the path of millions of first-generation Americans into the professional universe. But where others opted for safe careers and high-paying positions in the civilian world, Bose ended up in the middle of a war. When I first spoke to him, he was sitting behind a desk piled high with packaged snacks in an office he also slept in. Bose was distractedly mixing a protein drink, talking about the need to stay in shape. After a few minutes he spent describing his life, it was clear that Bose is an unlikely soldier. In 1996, after his first year of medical school, he took a look at his tuition bill and joined the Army, accepting a deal where the military would pay for a year of education for every year of service.

"It was a tough decision but you have to pay back the debt somehow, and I could have ended up with about $200,000 of debt. My parents were struggling with it. There were a couple of choices; I could work 23 hours a day and pay it off or pay it off at the age of 50. You don't know what's going to happen so you don't know if it's a good decision or a bad decision. If you lose an arm or a leg it's a bad decision," he said without irony. In six years, he reasoned that he would be nearly debt-free, having paid it back in an honorable way by serving the country.

The Army, for its part, took a look at Bose, saw his quick mind and his skill as a surgeon, and sent him to Iraq where he is now treating a steady stream of Americans and Iraqis for an enormous range of injuries, many of them horrifying. Bose also has the distinction of being the only board-certified physician in emergency medicine for 135,000 Americans and an unknown number of Iraqis. He will treat anyone who comes through the door.

I wanted to know what it was like to practice medicine during a war, so I asked to follow Bose to his medical platoon at the forward base in Khadimiya. There I would see what defenders of the war mean when they insist this is a humanitarian endeavor, that U.S. forces are doing good deeds for Iraqis. I witnessed Bose and his colleagues doing their best to help ordinary Iraqis, along with many other soldiers of the 1st Cavalry. But outside the base, their honest attempts were crippled by resentment and mistrust on both sides. Members of the 1st Cavalry couldn't rely on their Iraqi partners like the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps to be a bridge to the local community, because they believe that ICDC forces stationed on their base were betraying them to the resistance. Medical missions out into the local community had to be kept short for security reasons -- temporary clinics that should have been available for a full day could only stay open for a few hours because of the threat of attacks, and the U.S. forces were attacked all the time.

The result is predictable. The assistance missions have become a kind of cat-and-mouse game that works like this: Organize a convoy, dart out to an impoverished suburb, provide assistance and then dart back to the base before the resistance finds out about it and fires a volley of rocket-propelled grenades. Whenever the soldiers leave the confines of the forward base in Khadimiya, they are risking their lives to do it, and often the Iraqis are not happy to see them. And yet Khadimiya, unlike Sadr City, is comparatively calm, and is thought to be a hearts-and-minds success story. "They love us here," one soldier told me. I learned later, after two missions with the 1st Cavalry, what he meant by love was a species of sullen tolerance.

"Watch out for Bose, he brings the rain," one of the E.R. nurses was telling me just before we got on the convoy to the forward base in Khadimiya. In this scorched climate, we could only hope for rain; the nurse meant that when Bose was around, they were always hit with mass casualties. Rain was bombings, convoy ambushes, nightmare firefights that brought in injured by the dozens. Bose works long hours when the rain comes, performing emergency surgery on the critically wounded. Because the patient load can spike so quickly, he spends his time between the forward base in Khadimiya and the combat support hospital, shuttling back and forth. But there still isn't enough of him to go around. When the staff of the emergency room talks about him, they always mention his intelligence. Bose, who has a great passion for medicine, gives you the impression of a determined physics student and seems detached at times, slightly dorky. But in five days, I never saw him hesitate over the name of a nerve, small bone or drug. It is not surprising. When Bose took his medical board examinations, he won the highest score in the country. To his colleagues, who have enormous respect for him, he is a star.

On Saturday, June 5, the date we were leaving for the forward base in Khadimiya, Lt. Chris Melendrez, the commander of Bose's medical platoon, arrived at the combat support hospital. Melendrez was there to pick up Bose and take him back to the base to take care of a soldier with a broken nose. When I met Melendrez, he was professional and focused on getting the convoy together. He called and made sure I was authorized to go back to the base. When I thanked him for taking care of all the details, he said, "Too easy, let's make it happen," his catchphrase. Melendrez is like Bose in some respects -- a young officer with immigrant parents -- but Melendrez is a committed soldier, a believer in the cause. Bose is an intellectual and an accidental soldier, and sometimes the two men might as well be from different planets.

Outside the hospital we piled into armored Humvees. On the ride up to Khadimiya, Bose and I rode in different Humvees, Bose in an armored one. There was very little conversation. Everyone was watching the road and the gunner was watching everything that moved on the street. When we were moving, Iraqi civilians stayed well away from the convoy, and when they didn't, the soldiers would give them the Iraqi hand signal that means "wait," an upraised palm with all the fingers brought together. They obeyed, knowing that driving anywhere near the American convoy was dangerous and invited bad luck. We arrived in Khadimiya safely.

After two months in Iraqi Baghdad, I wasn't prepared for the base. I expected the same bombed-out structures that served as makeshift shelters for the 1st Cav soldiers, but the base wasn't like that at all. It looked like a typical, pleasant if unusually racially integrated American suburb. If you could forget about the incoming mortars and the war all around it, Banzai Patrol Base was a utopian island. Saddam built his Information Ministry at a bend in the Tigris River, shaded by rows of palms, and it now serves as a place where American soldiers keep fit by running along the graceful roads winding through the campus. Heavy-metal music poured out of the gym next door to the Internet cafe. The soldiers watch movies and MTV, and make discount phone calls home at the local smoothie bar/Internet cafe. At a chapel near the Internet cafe, stacks of camouflage Bibles and plastic rosaries wait for the faithful. Later, when I was thinking about the base, and missing it, I realized that the soldiers who live here will go home to a country that is far more divided than this community. The noisy, tumultuous Iraq of teahouses, sun-beaten men selling propane from donkey carts and black-veiled women struggling down the streets full of brutal traffic had been rendered invisible.

We arrived at the aid station where Bose works as the frontline surgeon, and dropped him off. Lt. Melendrez then offered to take me on a driving tour of the base. Melendrez, who is in his mid-20s and looks like he wouldn't be out of place on a pro baseball team, has a lot going on. He would reveal his intelligence and sensitivity in the space of a few days, but these are qualities that edged past his adopted persona as a platoon commander. We drove toward a row of single-story buildings, where two Iraqi ICDC trainees were walking down the center of the road, blocking the way. They knew we were behind them, but they didn't move, keeping their backs toward the car, and this infuriated Melendrez. "See that? They do this kind of thing all the time," he said. When we finally passed the trainees, there was no acknowledgment, no greeting, which is uncommon for Iraqis. It was the first sign that something was wrong.

I asked Melendrez what he thought of the ICDC recruits. "I don't trust them farther than I can throw them," he said with some bitterness. The young officer then told me about the problems they had been having on the base, and said that one senior Iraqi officer, who had been trained by the Americans, had been the target of an arrest raid by the 1st Cav. Melendrez said that the Iraqi officer was accused of plotting against the Americans, but that he disappeared before they could find him. Soldiers on the Khadimiya base talked about the suspect loyalty of the Iraqi forces every day. It reached a peak whenever the base received accurate mortar fire from across the river.

Unlike Bose, who is even-tempered, Melendrez is outraged at the thought that the Americans are being betrayed on their own base. Just thinking about the Iraqi soldiers gets him going. He didn't like the ICDC, but they were part of the U.S. plan, so he had to work with them. Melendrez wasn't alone in his take on the Iraqi forces. All of the soldiers I spoke to felt the same way; their distrust of the ICDC verged on hatred.

Melendrez would have to travel with a few of the soldiers he distrusted the next morning on a medical assistance mission to a slum town called Badiat. Badiat was on the outskirts of Baghdad, a village where people farmed poultry and recycled debris. He planned the trip carefully and briefed his people in the evening in his office at the aid station. Melendrez chose the order of the vehicles, the time of departure, the route and who would be going. His men watched while he stood at the white board and went over the mission. The convoy would stop just outside Badiat and they would meet up with the local leader, then continue with him to a local school and set up the temporary clinic. Because there has to be at least one medical officer at the aid station, Dr. Bose elected to stay on the base, and his colleague Lt. Dean Stulz would go instead.

Bose, the brainy outsider, didn't seem excited about the Badiat mission. He skipped Melendrez's briefing and hung out in his room in his vast library of packaged food gifts from home. After noticing that the two men kept their distance, I began to think of Melendrez as the anti-Bose, a bearer of prejudices he couldn't beat, a man who was anything but detached. "You have to be hard with these people," he said to me, talking about the Iraqis. "That's what they understand." Bose would never fall prey to empty wisdom like Melendrez's comment about the Iraqis, even if he found them to be difficult patients. Bose often treated wounded fighters who came into the emergency room spitting and glaring at the doctors. "You could tell they didn't want to be there." It was the harshest comment he made about people who were working hard to kill and maim his friends. Melendrez, who has a short fuse, has much different feelings.

The next morning, guarded by three Bradley Fighting Vehicles, Melendrez's convoy made its careful way out to Badiat. We turned off the main road onto a dirt track, raising a comet's tail of dust. A stench came through the windows because we had entered a dump operated by freelance garbage men. Dunes of trash covered the open ground. On the other side of the rotting hills was Badiat. The first Iraqis we saw were middle-aged men straightening rebar on sawhorses. One older man took the bent rebar from a pile and worked the kinks out of it by hand, then put it in a few piles; he was dirty and the sweat ran down his face.

Melendrez got down out of the car, spoke to the rebar-straightener through an interpreter and asked for the local leader. "He's not here," the man said and glared at us. It probably wasn't true, but Melendrez was unfazed and decided to go on to the school. Half a mile down the road, the Bradleys set up a perimeter while Dean Stulz and his medics created a clinic. It took them about 20 minutes before they were ready to see patients. Since the soldiers couldn't tell the people of Badiat exactly when they were coming for fear of ambushes, citizens emerged from their houses, looking at the armored convoy with a mixture of apprehension and curiosity. A Humvee with loudspeakers drove around town advertising the clinic. At first they trickled in, but before long there were at least 150 people waiting for free medical care under the brutal sun.

The very sick arrived an hour and a half later, their families carrying them in somber processions. Lt. Stulz, the steady Minnesotan who volunteered for the Badiat mission, saw more than 40 patients in a three-hour period. I watched most of them come in to see him. The Iraqis filed into the clinic/classroom with various ailments, some life-threatening, where they were treated or comforted and filed slowly out. One diabetic old man walked in with gangrene that had turned five fingers on his hands pitch black. Stulz would make an appeal for emergency surgery for this man when the convoy made it back to the base. Desperate parents brought him children with birth defects, heart murmurs. They kept coming, and Stulz saw them one after the other. Inside the clinic, there were spontaneous demonstrations of joy and gratitude for Stulz and his medics. Outside, however, tempers were fraying.

At the school gates, Melendrez and his soldiers struggled to maintain an orderly line of patients. The people from Badiat asked for water, and to get out of the blazing sun, but the soldiers were hesitant to let them inside the school because they didn't feel that they could control them. As midday approached, the mood of the crowd turned sour when the Iraqis realized that there was no way everyone could be seen before the 12:30 deadline when the convoy was scheduled to leave. At least once, Melendrez threatened Iraqis trying to push their way past the gates with his baton. When he raised the baton, the crowd would edge back slightly. Women were pleading to get out of the sun, to see a doctor. They petitioned anyone within earshot who would listen. Melendrez finally lost his patience with the crowd and slammed the school gates closed. All the men and women were pushed out of the way, back into the street. It was difficult to watch.

I was outside, standing near the school, when a man named Ahmad Naif said that he wanted the Americans to go away. A young boy who lived nearby lifted his shirt and showed an old bullet wound he said he got from the U.S. soldiers. "They thought I was an Ali Baba," he said proudly. Ali Baba is the universal term Iraqis use for thieves. Other men in the crowd said they didn't like the Americans, and at one point a crowd of young boys yelled at the soldiers to leave while their parents tried to silence them. A few minutes before the kids started up, Sgt. Robert Paul, a soldier assigned to a Civil Affairs unit, said, "The insurgents want to attack us and turn the mission into a failure, make it seem like we can't help anyone without getting people killed." Paul stood outside and looked at the restive crowd of Iraqis. "See that?" I saw only citizens waiting in the sun. "The ICDC are all inside the walls of the school. That's not good." Paul was right, the ICDC were all inside the school where it was comparatively safe.

Just before we left Badiat, the soldiers handed out candy and T-shirts. It was a mob scene. Kids, running, jumping, snatching things from each other. At 12:30 sharp, we climbed back into the vehicles. Back at the base, I fell into an exhausted sleep for the rest of the day.

The medical mission to Badiat was the first of two daytime missions. The second wasn't medical. On Tuesday, the commander of Charlie Company from Khadimiya was going out on an administrative house call. A young Tennesseean named Patrick McFall was going out to Sobibor north of Baghdad to meet with the Neighborhood Advisory Council on city business because in the absence of a legitimate Iraqi authority, McFall is working as their Irish-American caliph. He was busy trying to award reconstruction contracts and explain how to apply for the ICDC and getting frustrated with the lack of progress. I rode out there in an armored hospital vehicle, which has no air conditioning and is as loud as a jet engine inside. When we arrived at Sobibor, the medics opened the hatch and treated Iraqi kids for various injuries; they dressed wounds and communicated as best as they could without a translator and it took no time at all before a crowd gathered. Soldiers from Charlie Company handed out more candy, which drew more kids.

It was impossible to move around and the mob wanted the notebook I was using, the pen, my watch. You can't have the watch, the pen, the notebook, I explained. They had a million repeated questions. Mister, where do live? Are you married? Do you have kids? Mister, Whatisyourname? The tall ones squeezed my biceps, testing their strength, tried to sell me Pepsi, forced me to record a speech into a tape player, showed me ancient wounds. They cheered and heckled. Meanwhile, their older relations watched balefully from across the parking lot. The Iraqi child mob swelled and roiled. Not one of them grabbed for my wallet. They were good. Charlie Company threw out more stuff when the mob dwindled. At one point the kids were chanting Bush's name. I retreated to the steps of the building where McFall was meeting with the local authorities.

Past the gates it was perfectly calm; the kids were outside near the vehicles. On the steps a few soldiers were providing security for the doors. This is where I met a man named Lt. McCarthy from Charlie Company, McFall's executive officer. I told him I had to take a break from the mob outside. He was sympathetic. "Last time we let about 20 of them inside the gates. Yeah, we did that because the Iraqis don't shoot at us when there are a lot of kids around." McCarthy paused for a second, then said, "But don't write that." I would hear this once more at Banzai, about children used as an insurance policy against attack. It could have been pure superstition but McCarthy believed it.

As it turned out, the members of Charlie Company had gone out to Sobibor under the threat of an ambush, and they were nervous about what would happen in the town. McFall had taken precautions by placing other vehicles on routes out of Sobibor, while the rest of the convoy circled the town. Not a shot was fired. McFall and his company were out there, exposed, to meet with local leaders who didn't understand what they were talking about. The men wanted to go home without facing another volley of rocket-propelled grenades.

When the candy was gone, we pulled out.

On the evening after the Badiat mission, a mortar landed and threw out a mushroom cloud of dust, but I only saw this later, after the concussion. I was standing, slightly puzzled in the moment after it landed, near the basketball court for the Khadimiya base. An American soldier ran up to me, all panicked and out of breath and asked me, "Tal Inglisi?" which is rough Arabic for "Do you speak English?" I said I was a reporter from California. "Sir, really sorry. We're looking for the individual calling in the mortar strikes. He's around here somewhere." The soldier ran off, and his buddies were doing the same thing, hoping to catch an Iraqi on a cellphone who was directing the mortar barrage from the base itself.

However they managed it, the insurgents have a perfect fix on their command post. Firing from across the river in A'adamiya, several kilometers away, the shells were landing within feet of the building, throwing shrapnel in every direction. Mortars have even dropped through into the courtyard. After the soldier went off to find his suspect, another mortar exploded close by so we sprinted into the basement of a nearby building. In fact, this was a fairly ordinary day at the base. At Charlie company farther down the road, they didn't even look up when the shells landed. In this particular barrage, there were no casualties, but soldiers from the base have been seriously injured in recent attacks and medevac'd to the combat support hospital.

Back at the aid station, I asked why the Special Forces didn't go out and find the insurgents behind the mortar attacks. The answer came back that the zone across the river belonged to another unit. "That's not us," the soldier told me. "At one time, we had all eight mortar positions mapped out, but we couldn't do anything about it." The man shrugged helplessly. It's the depressing accuracy of the mortar attacks that makes everyone on the base think there's a rat on the inside.

Angry sermons from the mosques across the river in A'adamiya came through the soft evening air. The wind mixed up the sound. Night was falling, and the temperature drifted out of the triple digits. Melendrez was hanging out talking to a few of the medics in front of the aid station when he caught sight of a soldier walking down the road in full battle dress. Melendrez couldn't stop laughing. "Shit. Look, it's Bose!" Bose had put on his flak jacket, goggles and helmet to walk back from the Internet cafe when everyone else was wearing shorts and T-shirts in the heat. Bose looked like an astronaut and I didn't recognize him until I could read his nametag. He was in full battle dress because he was worried about mortars that kept landing near the command post he had to skirt on the way to the aid station.

"It's all fun and games until someone loses an eye," he said when he walked up. Melendrez looked at him like he was insane. But instead of laughing, all the medics nodded, because they knew it wasn't a joke. There has been an epidemic of blindings in Iraq. Roadside bombs blow in the windows of the vehicles, destroying soldiers' eyes. Mortars send out shrapnel that has the same effect. It happens all the time. Bose has a horror of death and he was careful; he was the smart one. The medics who worked with him were fine with Bose all dressed up for his walk across the base. It made sense that he was careful. They needed him.

Melendrez told me about Bose's soldiering before the Badiat mission. "He's really smart, but he's so dumb about the Army." The platoon commander explained to me that everyone is supposed to qualify on at least one weapons system. "I think he went out with the M16 and finally qualified after seven attempts. They might have said, 'OK, he passed.'"

I told Bose that I heard he couldn't shoot. He thought it was incredibly funny, and he laughed. "Yeah, you know, if I have to start fighting, we're going to be in a lot of trouble." If it bugged Melendrez, who loves the Army, it didn't bother anyone else.

Later, I asked Bose what upset him the most about practicing medicine in a war zone. "Pronouncing people dead is the most disturbing because they came here just like I did, waved goodbye to someone, expected to be back and then they don't come back. The blood and guts is OK, I can deal with that, but there is a level of attachment with a patient that is not there in the States. It hits closer to home here. My patients are people in this unit, the people I ate breakfast with that morning and now they're injured. That has happened. But you just detach and do your job, just detach and do your job."

Shares