"While it's harder for me to step back than step forward, today I step back," Andrew Cuomo, former U.S. secretary of housing and urban development and New York gubernatorial wannabe said Tuesday afternoon as he announced that he was dropping out of the race one week before the primary. "We need healing now, maybe more than ever before," Cuomo said. "I'm not going to start dividing now."

But the only division Cuomo seemed able to create was one between himself and the electorate.

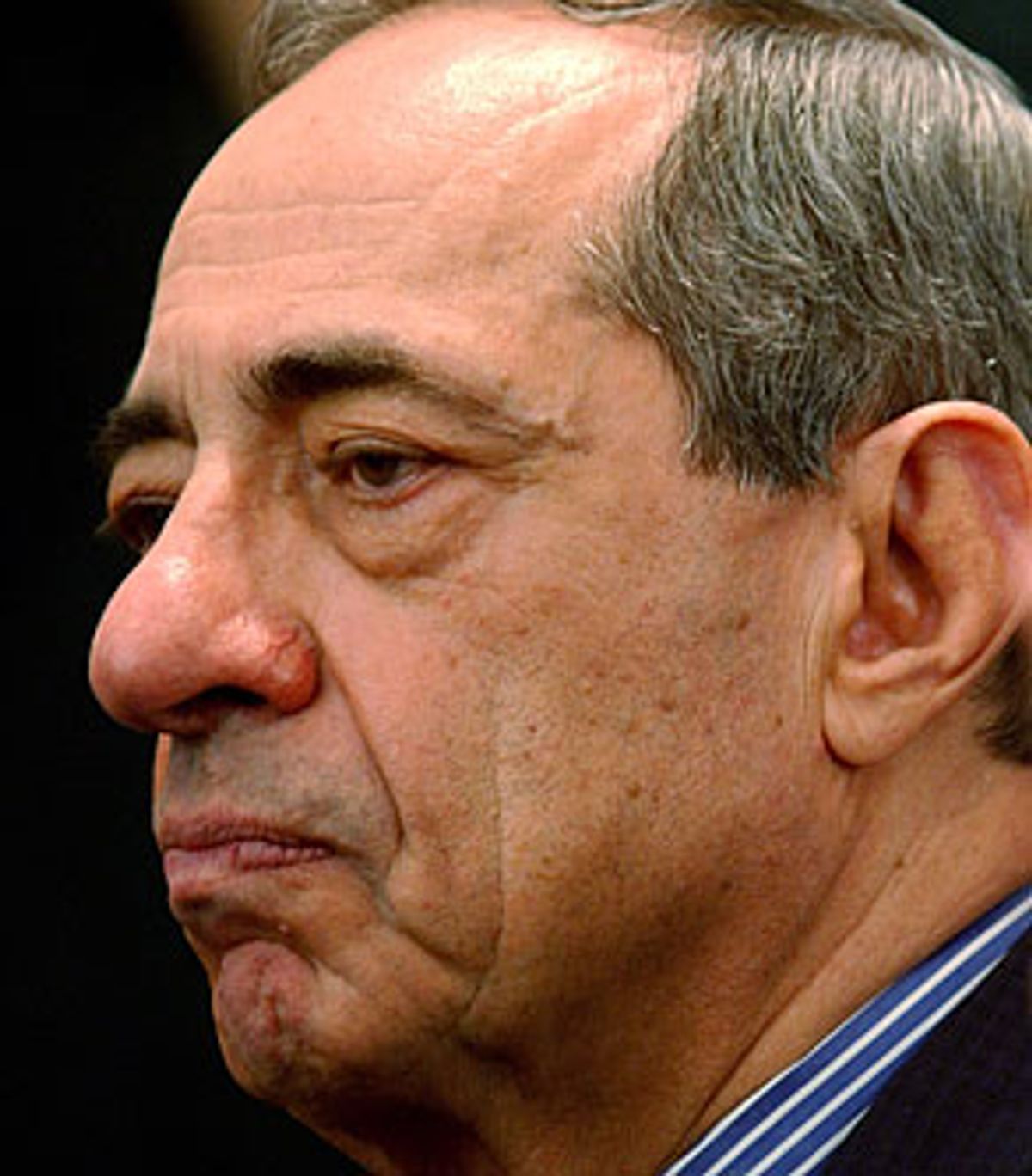

Empirically, it is nothing short of remarkable that Cuomo -- the 44-year-old son of and enforcer for three-term Gov. Mario Cuomo, President Bill Clinton's secretary of housing and urban development for three years, and husband of former New York Sen. Robert Kennedy's daughter Kerry Kennedy Cuomo -- was well on his way to being trounced in the primary on Sept. 10, despite having entered the race ahead in the polls and having raised more money than his opponent, the state comptroller, Carl McCall. An Aug. 26-Sept. 1 poll released Monday by the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute indicated that, including those voters leaning in one direction or another, McCall leads Cuomo 53 percent to 31 percent among likely primary voters and was only widening his margin of likely victory.

On its face, the news that Cuomo was withdrawing from the race might take non-New Yorkers by surprise. But to those who have come in contact with Cuomo and seen how his grating personality has sullied what could have been a promising campaign, his withdrawal was surprising only in that it was a rare moment of grace. Characteristically, amid what could have been a dignified exit, came reports that in exchange for his taking leave, Cuomo was acting up again, blaring his obnoxiousness for all to suffer.

In exchange for his exit and endorsement, Cuomo demanded that McCall give him a high-profile role in his campaign, that former President Clinton be presented as the "broker" of the peace between the two Democrats, and that McCall endorse Cuomo's gubernatorial run in 2006 -- a request that assumes McCall will lose to Republican Gov. George Pataki this November.

According to a source close to McCall, the comptroller's response to the three requests was: "No, no, no."

The tacit threat was that if McCall didn't acquiesce to Cuomo's demands, he would spend the $3 million he has in his campaign coffers on negative ads against McCall. In his speech, however, Cuomo tried to play the statesman. "We still have an open wound that we are dealing with from last year's Democratic mayoral election," Cuomo said in his farewell address, referring to last fall's bruising and divisive primary match between former New York City Public Advocate Mark Green -- another obnoxious Democrat -- and Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer. Green won the nomination but in doing so alienated key parts of the electorate, helping Republican Mike Bloomberg to win the election. "If we were to now spend $2 million this week on an acrimonious campaign, we would only guarantee a bloody and broke nominee, whoever won, and the ultimate success for Governor Pataki in November would be assured."

"When you try to communicate too many ideas, sometimes you wind up communicating nothing," Cuomo said, Clinton by his side. But in the end all Cuomo seemed to communicate was that he is a very unpleasant person.

In an interview with Salon last week, McCall addressed some of Cuomo's personality issues. Cuomo's ability to alienate was almost unparalleled. Cuomo, after all, was a loyal Cabinet secretary during the Clinton administration, yet few of his former colleagues supported his campaign. Why would that be?

"They know him, what can I tell ya?" McCall said.

McCall said he'd spoken with several former Clintonistas and while he begged off from going into the details of the conversations he described them thus: "Having worked with him, they're not very supportive."

Far from being seen as merely "brash" or "arrogant" -- words more refined publications use to describe him -- the regrettable fact for Cuomo was that to a sizable number of voters he seemed like an asshole. And sometimes a politician's problems are truly that simple.

Some of Cuomo's electoral dysfunction is due to both the methodical and historical aspects of McCall's candidacy. Arguably, the nomination has always been McCall's nomination for the asking. While Cuomo spent much of the 1990s in Washington, McCall served the state as a prominent, statewide, Democratic, elected official; plus, if elected, McCall would be the first black governor in state history. But the perceived odious combativeness of Cuomo's persona cannot be understated. It affected his relationship with other Democratic officials, with reporters and ultimately with voters.

One New York Democratic officeholder who asked to not be identified recalls his first encounter with Cuomo. Early in the campaign, Cuomo "had such a reputation -- both negative and positive -- as the guy who would run through fire to get elected," the officeholder said, that people were intrigued by the notion of his candidacy. Even this particular officeholder was intrigued, although he was "75 percent there to be with McCall." So when Cuomo phoned to try to win his endorsement, he took the call.

"I was absolutely offended by how crass he was," the officeholder recounts. "He said, 'The blacks are sticking together so much, we have to be as vocal as they are.' When I heard that from someone trying to claim the Kennedy mantle, someone whose father was so progressive on racial issues, him making that kind of racial appeal, I was taken aback.

"Andrew, before you called, I was concerned you were going to have a 'Mark Green' problem," the officeholder told Cuomo. "Now I'm even more concerned when I hear rhetoric like this." To this, Cuomo said that the day after he won the gubernatorial primary he would bridge the racial divide, appearing with black leaders like the Rev. Jesse Jackson. The officeholder decided to endorse McCall.

The Cuomo campaign did not return repeated phone calls for this story, nor would the campaign make Cuomo available for an interview despite several requests.

This kind of attitude has apparently seeped into almost every campaign move Cuomo has made. Other than celebrities like Joe Pantoliano (über-obnoxious Ralph Cifaretto on "The Sopranos") and ex-office holders of Italian descent closely allied with his old man (like former Rep. Geraldine Ferraro), Cuomo has a dearth of endorsements; the New York Times and the New York Post have endorsed McCall.

Perhaps more importantly, some private polls placed Cuomo's "negatives" -- the percentage of voters with an unfavorable opinion of him -- in the low 30s among likely Democratic voters, an astoundingly high number. It hurt him in comparison with the "nice-guy" perceptions of both McCall and the man both he and McCall hoped to defeat this November, George Pataki. Since there are few actual policy debates to be had in this primary, much centers on personality.

"In a primary, a lot has to do with style and image because there aren't a lot of substantive differences," one New York Democratic operative says. "And Andrew fails those tests."

But it's not just a question of style. According to former Clinton administration officials, Cuomo as both undersecretary and then secretary of housing and urban development was difficult to work with and had a management style of questionable effectiveness. Morale at HUD during those years was low, many say.

On the campaign trail, Cuomo tried to portray himself as "an aggressive progressive," contrasting his brash ways with McCall's more subdued temperament. There may be something to this; in its Sunday endorsement of McCall, the New York Times editorial page ceded that "a candidate with Mr. Cuomo's spirit and Mr. McCall's experience and gravitas would be hard to beat." But since such an amalgam was unavailable, the Times chose McCall with little apparent hesitation.

Maurice Carroll, director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute, says that Cuomo gets a bad rap. "I've known him since he was teenager in Queens fixing cars to make extra money in his family's driveway," he says. "He gets knocked for being an aggressive politician, but most politicians are aggressive. Maybe he's a little more overtly aggressive."

There is indeed much about Cuomo to like. In 1986, at the age of 28, he started an effective charity for homeless families, Housing Enterprise for the Less Privileged, or HELP. As a HUD secretary he was passionate, fearless and energetic. For those looking for brave liberals, Cuomo as HUD secretary bravely took on the Klan and the gun lobby; for those looking for someone who would take on entrenched liberal bureaucracies, Cuomo did attempt to reform public housing and achieved some successes. He is bright and interesting.

And, to an extent, the rap on Cuomo as a "negative campaigner" is unfair. McCall has also been critical of Cuomo's record, as Cuomo has been of McCall's. Both records are of course fair game. Only recently has McCall refrained from doing so, as his polls shot up and he seemed to be pursuing a strategy of running out the clock.

Their differing styles were apparent during last Wednesday morning's debate on "The Brian Lehrer Show" on WNYC-FM, the local National Public Radio station. McCall, 66, sauntered in, arriving a touch early. Waiting for the debate to begin, he leaned his head on his hand wearily. He seemed mellow -- a rumpled cool, even, if perhaps a bit sleepy.

When McCall speaks, he seems far more like the Citicorp vice president he was for eight years or the former president of the New York City Board of Education than the somewhat militant columnist for the Amsterdam News he was in the 1970s, where he once even bashed Santa Claus as "no friend of the ghetto child." The Carl McCall of 2002 generally seems more cautious than the average black politician, which Cuomo has tried to underline. In a campaign appearance with Cuomo, fiery African-American studies professor Cornel West called McCall "a timid and hesitant man."

This is not quite fair. McCall has taken both Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Gov. Pataki to court. (Giuliani was trying to keep McCall from auditing several city agencies to gauge their effectiveness; Pataki was proposing a budget that would have used $230 million from the New York State and Local Retirement System.) Regardless, McCall's methodical and cautious nature can be seen as a plus by some. He has proven effective in his supervision of the state's $112 billion stock portfolio. Moreover, his personal story -- his rise from the slums of Boston to prestigious Dartmouth College to the corridors of power -- is a bit more compelling than that of Cuomo, who is something of a Queens version of George W. Bush, plus a few I.Q. points and minus a great deal of bonhomie.

McCall just generally seems more pleasant; Cuomo kind of seems like a dick. And it is perhaps for that reason that campaign blunders that would take another candidate out -- the discovery that McCall had not, despite his claims, been raised in public housing (though certainly his childhood was fairly squalid); the revelation that McCall's running mate had fathered several children outside his first marriage; the slam by supporter Rep. Charlie Rangel, D-N.Y., that Cuomo's wife wouldn't be a factor in the election since "No one knows who she is" -- have quickly dissolved and disappeared.

At 10 a.m. on the dot, Cuomo appeared at the end of the WNYC's hall, and he brusquely bee-lined for the studio like a jungle cat. The debate began and it didn't take long for Cuomo to kick in with one of his criticism staples, slamming McCall for having "certified" the state budget -- in essence, for not staging a protest against Pataki's budget priorities by withholding paychecks for the Legislature. His nature is the attack, the rat-a-tat-tat, the game of it all. You could tell he loves combative politics, loves drawing blood.

"Why didn't you say, 'I'm not signing! It's a sham budget! I'm gonna be the guy who stops the dance!'?" he asked McCall. The implication was that McCall should have created a standoff not unlike the Clinton vs. Gingrich government shutdown, refusing to carry out his comptroller's duties and verify that the appropriations bills are sufficient to cover the state's expenses.

"This is the difference in the campaign," Cuomo said, "the issue is who will actually get something done? Past is prologue. Someone has to stand up and say 'Stop!'"

And since this was a debate with a Latino focus, cosponsored by El Diaro, Cuomo added, with all the subtlety and ilan of his friend Al Gore, "No mas palabras solamente obras -- no more words."

McCall brushed this aside. "He's just trying to be petty and critical," he told Salon about Cuomo's budget attack. "I don't think he understands the process." McCall said if he had done what Cuomo suggested he should have done he would have been "grandstanding -- it would be doing something that would get me a lot of attention, but it wouldn't enhance the process."

Whether or not it's a fair criticism, Cuomo made the charge over and over in his brash style, which hurt him. Questions about Cuomo's personality issues may have been first voiced in April ago when, attempting to deflate Pataki's post-9/11 image and daunting personal approval ratings, he slammed the governor as having provided little leadership in the wake of the terrorist attacks compared to Giuliani. But Cuomo's slam that Pataki merely "held the leader's coat" ended up backfiring on him and became a gaffe with legs.

McCall pointed to a different episode in Cuomo's campaign as being the one that caused his challenger the most problems. During the state Democratic Convention in May it became clear that Cuomo's attempts to woo delegates had been relatively fruitless. He left the convention, saying that he would secure a spot on the primary ballot by obtaining 15,000 signatures rather than by earning the public support of 25 percent of the delegates. "I want to be the candidate placed on the ballot by the people, not the party," Cuomo said at the time.

"These were people who he had spent a year courting," McCall told me. "He'd been asking them for their support, telling them that their support was important, and then when he didn't get their support he decided something was wrong with the process, and said these people were hacks. Everybody saw through it. If I have a lead today it's because people saw the hypocrisy of his position."

Some say that Cuomo has his strengths but was just the completely wrong guy for this particular moment in the Empire State zeitgeist. "I think there might be some elements of this about our changing demands of our elected officials, maybe especially after 9/11," says Rep. Anthony Weiner, D-N.Y., a McCall supporter. "Maybe we wanted a bull in the china shop after [former New York City Mayor] David Dinkins. Maybe we wanted someone more conciliatory after Sept. 11, like Michael Bloomberg," who defeated the combative, arrogant-seeming Mark Green.

"I think Cuomo just misjudged the ethos right now," Weiner says. "He clearly thought we were more upset than we are."

A senior McCall advisor says that his campaign had run some of Cuomo's campaign themes by voters through polling and focus groups and they have consistently tested poorly. "This whole 'shake things up,' 'New ideas' pitch, there is absolutely no indication that's what people want," the advisor says. "They want a steady, mature leader. If anything, things have been shaken up enough in New York."

That spirit may end up biting McCall in the bum, too. While his supporters continually point out that when he was reelected comptroller in 1998 he won even more votes than did Pataki, Pataki still trounces him in hypothetical matchups. Though in a state with a flailing economy and 2 million more Democratic voters than Republican ones, it's difficult to assume that Pataki has it locked up.

Cuomo, meanwhile, was in a box -- behind in the polls for being perceived as too negative, he was, in a way, prohibited from attacking, the one thing that underdog candidates do in such situations. At a Thursday debate at a Rochester public television station, Cuomo -- who had been previously trying to portray a more subdued self because of these high negatives -- goes for it anyway, criticizing the culture of Albany. Of course Cuomo was part of the culture of Albany for quite some time himself as chief advisor to his father.

"Stop the excuses," Cuomo said directly to McCall. "Stop the reasons why you couldn't do anything for nine years. You were there."

Albany is a cesspool of quid pro quo sleaze, but perhaps if Cuomo were more of an actual outsider the charges would seem more credible. McCall told Salon after the debate that Cuomo's attempts to portray himself as "the ultimate outsider" were "amusing. Most people find it amusing."

Last Saturday, Cuomo released a new TV ad. The McCall team had expected it to be negative -- What else could he do to shrink the lead? But, caught in a campaign dynamic -- shaped, perhaps, by Mario's failure to slap his son upside the head a few more times when he was a young punk -- the ad was instead a positive one about protecting Social Security. Snore. The ad is notable in that Cuomo doesn't speak or address the camera at all. In its Tuesday analysis of the ad, the New York Times wrote that "Political analysts have said keeping Mr. Cuomo out of the way may help with the many voters who, polls suggest, are inclined to dislike him."

Cuomo's announcement Tuesday simply confirmed what many Democrats have been saying for weeks. "The race is over," the New York Democratic officeholder said Monday, before news of Cuomo's withdrawal. "The only question left is: How bad is Andrew hurting his future? The truth is, he's probably hurt it pretty bad already. But the question now is: Is he going to devastate his future by going very negative on McCall?"

Cuomo served as his father's senior advisor and often filled the role of backroom enforcer. In 1993, he was appointed an assistant secretary at HUD. When HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros announced his pending retirement, Cuomo campaigned aggressively to replace him -- so aggressively, in fact, he was told privately by White House officials to back off. Cuomo began speaking about returning to New York, but then the leading contender for the HUD job -- Seattle Mayor Norm Rice -- suddenly saw his chances shanked when a homeless advocacy group accused him of misrepresenting facts in an application for a $24.2 million loan guarantee from HUD. Cuomo had received a memo from a Seattle HUD official about this possible malfeasance in 1994. A HUD investigation ultimately cleared Rice of any wrongdoing, but by then Cuomo had the job.

He won't get this one, however. After last week's Rochester debate Cuomo told reporters that his lack of traction in the polls was because his "advertising has not communicated the message of the campaign well enough." But sometimes the reality is so clearly unattractive no amount of advertising is enough to cover it up. That's the lesson conveyed by the news that since last Sept. 11, the Saudis have spent more than $5 million in a U.S. public relations campaign but they've only seen American opinion turn against their al-Qaida-supporting country even further, its negatives increasing from 50 percent in May to 63 percent today.

The senior McCall advisor suggests that Cuomo did have a point about his ads. The McCall campaign has shown some of Cuomo's TV spots to focus groups and they've been put off by how he seems -- particularly in one ad running in upstate New York about jobs, "in which he's almost yelling," and another aimed at New York City about corporate accountability, "and he's got too much of an edge in that one, too."

"It's a cool medium," the advisor says. "People don't like it if you're too hot. You don't want to come across as a wiseguy, or too aggressive."

"There's a difference between being energetic and being aggressive," McCall told Salon. "I think I'm energetic on the stump and on the campaign. Yes, I am mellow and I am mature. But I can be tough and aggressive when I need to be."

With the nomination now effectively in hand, McCall says, he will be aggressively criticizing Pataki's record. "But I'm not going to do it in a nasty way, or in a way that turns people off. You need to show people a little balance."

Does Cuomo have that balance? "I haven't seen it yet," he says.

Shares