John Passacantando, the executive director of Greenpeace USA, believes in confrontation. A protégé of Mike Roselle, co-founder of the radical environmentalist group Earth First, he's led Greenpeace to push the limits of civil disobedience. On his watch, the group has boarded ships involved in illegal logging. He and other activists have chained themselves to the entrance of the Environmental Protection Agency and dumped barrels of contaminated waste at Dow Chemical's headquarters. Last year, he told a reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, "I want Greenpeace first and foremost to be a credible threat ... To paraphrase Thoreau, I regret only our good behavior."

So one might expect Passacantando to be thrilled by the prospect of bad behavior, and a lot of it, at the Republican National Convention late this month. Tens if not hundreds of thousands are expected to take to Manhattan's streets in protest, and plans are being hatched for widespread disruption, from shutting down city streets to throwing pies to assaults on the offices of "war profiteers." But Passacantando isn't happy about what's about to happen in New York. In fact, he's terrified. Like a host of intellectuals, '60s veterans and activists desperate for a John Kerry victory in November, Passacantando worries that the delicious, so-close prospect of defeating George Bush in November will be swept away in the citywide chaos that anarchists have promised to bring to New York.

"The potential for violence is worrisome, and the potential to have it boomerang against progressive policies is great," he says. "People watching this convention will be judging the Bush administration on its policies, but they will also be judging the people in the streets."

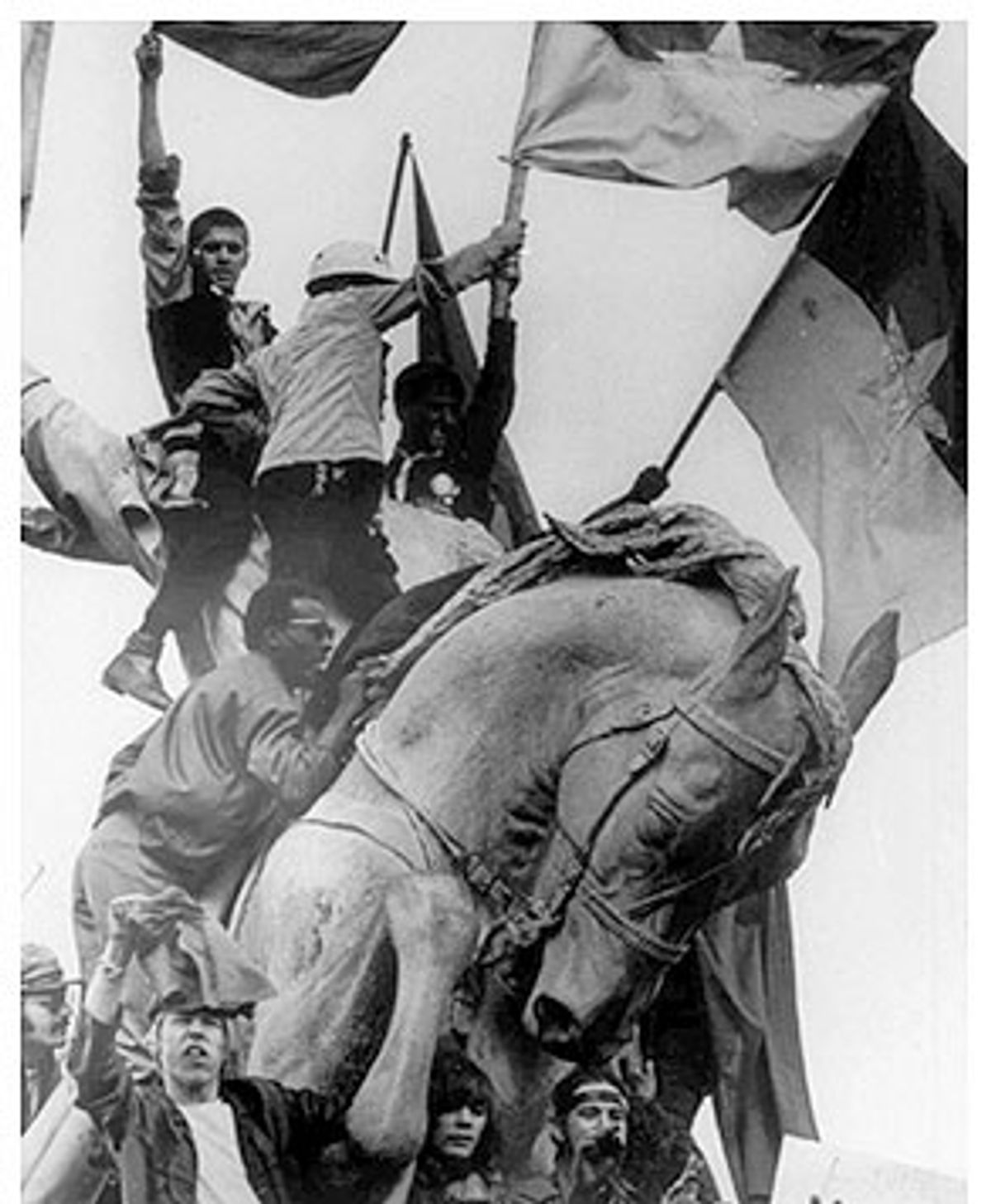

There's a grim precedent for left-wing protest that empowers the right: the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. The parallels between the convention protests that year and those expected this year are striking. Then, as now, the antiwar movement was coursing with justified rage. Chicago Mayor Richard Daley took an even harder line against protesters than New York's Mayor Michael Bloomberg, refusing to grant any permits at all.

There was a radicalized, street-fighting contingent among the demonstrators who released stink bombs in the delegates' hotel, vandalized a CIA building, and engaged in other mischief, but most of the protesters were peaceful. The violence that erupted, leading to days of running street battles, was by most accounts the fault of the police. Phalanxes of cops charged into crowds, beating protesters bloody, spraying mace, and chanting "kill, kill, kill." A report to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence called the debacle a "police riot."

Thus the demonstrators assumed that public sympathy would be with them, the victims. They were wrong. "To our innocent eyes, it defied common sense that people could watch even the sliver of the onslaught that got onto television and side with the cops -- which in fact was precisely what polls showed," writes former antiwar organizer Todd Gitlin in his 1987 book, "The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage." Indeed, many people believe that the fighting in Chicago helped cement the victory of Richard Nixon, who, as Gitlin notes, won the popular vote by a mere two-thirds of 1 percent.

A similarly minuscule margin could determine this year's election, and the possibility of history repeating itself leaves Gitlin aghast. "I think the Republicans will probably do what they did in 1968 and make television commercials of people rioting in the street and then promote their guy as the superintendent of order," he says. "I sure wouldn't want to be explaining to my kid how it turned out that Bush won election by three electoral votes because of some last-minute surge of opinion in West Virginia where that commercial played three times an hour." Gitlin and Passacantando's anxiety led them to coauthor an article in the Nation warning that the RNC 2004 could be Chicago '68 all over again unless progressives exercised restraint during the convention protests.

Milton Glaser, the legendary graphic designer behind the I Love New York logo, has thought about this prospect a lot. He knows the power of images, and he's scared that pictures of rampaging protesters flashing on the nation's TV screens during the Republican National Convention will be a catastrophe.

"A lot of people in this town are very angry," he says. "When you have so many angry people up against the police, without any question violence will occur. If this turns out to be the visual material that the country is looking at, there's just the chance that there will be an incremental turn towards Bush."

For protesters desperate to unleash four years of frustration, though, such warnings are easily dismissed. "Just talking for my own perspective, it would be a stretch to base the expression of one's dissent on the question of whether or not it would energize the right wing," says Jason Flores-Williams, an anti-RNC activist and political writer who recently authored High Times' guide to the convention protests. "First off, you've got to do what you've got to do for yourself. I'm less concerned with how things are going to affect the vote, and more concerned with confronting the systemic problems in this country head on." Just as a previous generation talked of turning New York into Saigon, Flores-Williams says that the goal is "to make New York reflective of the anger that's inside of us."

This kind of thinking exasperates Gitlin. "The meaning of events is sum of all the consequences," he says. "There's a deep divide between those people who are capable of thinking through consequences and those people who are either incapable or resistant to thinking through consequences."

The divide between liberal pragmatists and radical seekers of self-realization is a perennial one, and there's a certain historical irony in the way it's cropping up now. After all, in the 1960s New Left student leaders like Gitlin, convinced they'd entered a new era where old political dynamics were obsolete, were notoriously dismissive of the cautions raised by their progressive elders. Electoral politics seemed to them a joke. "A fierce moralism had brought us into opposition in the first place, and the same moralism didn't brook the politics of lesser evils," Gitlin wrote in "The Sixties." He didn't vote in either 1964 or 1968, and by the end of the decade his cohort had broken with erstwhile liberal allies like Irving Howe.

Three and a half decades later, Gitlin is condemned to play out a similar scenario from the other side, the aging former radical shaking his head at stubborn, volatile militants. The new generation of direct-action aficionados is tired of worrying about what Middle America thinks, especially if it means sublimating their own needs. "I don't see this budding movement being in any kind of dialogue with mainstream America," Flores-Williams says. "Mainstream America is going to work and turning on the TV, and they're going to think what they're going think regardless." A frustrated Gitlin says, "I don't know how to persuade someone who believes in recklessness and is cavalier about consequences to be a responsible person."

The divide between liberals and radicals is starkest on the issue of violence. Many liberals, including Passacantando, repudiate violence of any kind, whether it's against people or property. "One cannot effectively or morally oppose the violence of the Bush administration by acting violently in turn," Passacantando says. "To do so is cowardice. For Greenpeace, it's very simple. Violence is damage to people or property. Period. Throwing something through a window, whether it's a building full of people or a building that's empty, is an act of violence. That's not a new definition. Martin Luther King gave parameters that tight and tighter. Gandhi was the biggest stickler of all on nonviolence."

For the most part, though, anti-RNC organizers aren't Gandhians. Few say they're planning violence, but many refuse to condemn it, especially property destruction. Indeed, in anti-RNC circles the very idea that smashing windows constitutes violence is considered risible.

Recently Bill Millard, an East Village writer, editor and musician, posted a suggestion on an anti-RNC listserve that activists should respond to the media's fear mongering by pledging, "publicly, loudly, with absolute seriousness -- to avoid and repudiate idiotic actions like triggering blackouts, harming horses, etc. That's right-wing provocateur behavior, not principled protest. Karl Rove couldn't think up a better way for this whole event to play right into the Repugniks' hands."

To Millard, the idea seemed like common sense, and he was surprised by the vehemence with which several activists rejected it. "Denouncing violence is the equivalent of attempting to minutely define who makes up a NoRNC coalition that's actually quite diverse and hard to pin down," wrote Eric Laursen, a member the A31 coalition, a group calling for direct action against the RNC on Aug. 31. "It just complicates the story for a corporate media that can't handle much in the way of subtleties."

Rather than repudiate violence, the direct-action faction of the anti-RNC movement is trying to convince the media that violence is solely the fault of the police. "The best way to address this stuff is by working really hard in advance to use a little rhetorical jujitsu, pushing the violence issue back at the cops -- where it belongs," Laursen wrote.

Thus, at an Aug. 4 press conference, the A31 Coalition sought to finesse the issue with anarchist cant. They'd called the conference in the hopes of dispelling some of the hysteria about anarchist mayhem that's been filling the tabloids. Organizers have been outraged by stories about demonstrators who plan to hurl bags of excrement or use gunpowder to trick police dogs and trigger evacuations, insisting that such tales are part of a police disinformation campaign. They wanted to set things straight.

The media packed into the meeting room at the East Village's St. Marks Church, where the conference was held. A Fox News microphone was prominent in the cluster at the podium. The dozen or so people from the A31 coalition sat arrayed before a frieze of the Virgin Mary and an angel, looking overwhelmingly ordinary -- nothing like the black-masked saboteurs the papers have been warning of. Among them were John Shields, the white-haired mayor of Nyack, N.Y.; Naomi Gordon-Loebl, an impish high school girl in baggy shorts and a buzz cut; and Jack Waters, a "filmmaker, artist, writer and urban gardener," who wore a T-shirt of an American flag on which the stars had been replaced by corporate logos. A few of their sympathizers sat in the crowd, including Jamie Moran, whose group, RNC Not Welcome, is devoted to aiding direct action against Republican delegate events.

The A31 coalition distributed a press kit, including a photocopied list of "War Profiteers and Other Corporations That Place Profits Before People" that will be targeted on Aug. 31. One by one, they gave short speeches, and then they all took questions. When a Washington Post journalist asked about "property violence," Waters responded, "As a green-thumb gardener, I've witnessed people who have planted trees, then see these gardens bulldozed. These are living things. It's very difficult for me to see the destruction of property as violence in relation to the destruction of living things."

This kind of rhetoric strikes many in the movement as self-evidently true, but it appalls Passacantando on tactical as well as moral grounds. After all, he expects that there will be provocateurs in the crowds at the RNC, trying to provoke vandalism and spark confrontation. As Gitlin notes in his book, a 1978 CBS broadcast reported that, according to Army sources, as many as one in six protesters at the Chicago '68 protests were really undercover military intelligence agents. There were local police and FBI agents planted throughout the antiwar movement, often urging their cohorts to ever more daring feats of resistance. Richard Nixon's White House relished riots, knowing they only helped the Republicans. On a larger scale, the FBI's COINTELPRO program used its agents to provoke violence in antiwar and civil rights groups throughout the late '60s and early '70s.

Passacantando sees the current administration as capable of similarly dirty tricks. "You don't have to be that much of a strategist to see huge potential for that again. You're dealing with an administration that has seemed to stop at nothing to accomplish its ends," he says. "Certainly you would not assume that the Bush administration is more moral than the Nixon administration." There have already been some incidents of agents posing as activists and trying to ratchet up confrontation. In Denver last year Darren Christensen, an undercover policeman working with the federal Joint Terrorism Task Force, joined an antiwar group planning a peaceful sit-in and shocked them by suggesting that they charge a line of armed policemen.

"In a supercharged emotional situation, provocateurs who mean it and provocateurs who fake it have a natural alliance," says Gitlin. "It's not always easy to know who's who. It doesn't take a lot of sparks to ignite people who hate Bush."

Some believe that's precisely why the Bush team chose New York in the first place. "I think it's a deliberate strategy," Glaser says. "They knew there would be violence in the streets."

The potential for unrest has likely been exacerbated by the city's long delay in granting permits for legal protests, and by its refusal to let demonstrators rally in Central Park, instead relegating them to the West Side Highway, a barren, isolated stretch of concrete. Earlier this summer, Democratic Assemblyman Richard Gottfried, who represents a liberal Manhattan district that includes Chelsea and part of the Upper West Side, released a statement suggesting that Republicans could be deliberately trying to create an explosive situation to help them in the polls. "In Chicago at the 1968 Democratic Convention, and many times in this city, we have seen the disastrous consequences when the city fails to deal reasonably and fairly with people who feel strongly about their views," Gottfried wrote. "There may be some of the Republican Party who think that provoking disruption in our streets will benefit them politically. The Bloomberg Administration should not be playing into their hands and jeopardizing our rights and public security."

To counteract such provocation, Passacantando suggests having monitors patrol the protests with handheld video cameras, which they'd use to record the faces of demonstrators who get violent, hopefully intimidating them into line.

He says he's spoken to United for Peace and Justice, New York's largest antiwar organizing group, about the idea and said they seemed interested. But UFPJ, which is sponsoring a huge march the day before the convention, isn't eager to alienate radicals. In fact, a memo is circulating among various anti-RNC factions, including UFPJ and RNC Not Welcome, in which the groups promise not to criticize each other's tactics.

This dismays Passacantando. "To on the one hand say we are nonviolent and wouldn't harm people or property and then on the other hand say, 'I won't comment on the tactics of others,' I don't think that works," he says.

It's not that Passacantando doesn't understand how angry people are. He's been doing battle with this administration since it came to power. "Post 9/11, we boarded a ship full of illegally logged mahogany coming in from Brazil to the port of Miami, and the Ashcroft Justice Department tried to destroy Greenpeace," he says. "We ultimately beat the Bush administration in the federal District Court, thus preserving everyone's right to engage in peaceful dissent, at least until Ashcroft's next volley."

But rage has to be used strategically, he argues, or it amounts to little more than a tantrum. "We have to take our own discontent about the horrors this administration is foisting on our world and we have to find a way to productively channel that anger into something that speaks to a larger audience, as opposed to just engaging in personal therapy," he says. "When you're doing something in front of the cameras, for the cameras, you have to take into account how will this be perceived."

Such thinking makes sense only to those who are worried about alienating American voters. Liberals are, but many anti-RNC activists defiantly are not. Ironically, despite being motivated by a ferocious hatred of George Bush, some of those planning direct-action protests against the convention have grown so disillusioned with electoral politics that they barely seem to care whether he's defeated in November.

Getting Bush out of the White House "is an aesthetic thing -- I won't have to look at him anymore," says the A31 Coalition's David Graeber, explaining his mild preference for Kerry. A 43-year-old anthropology instructor at Yale, Graeber, who lives in Chelsea, says, "Maybe I'll vote for Kerry, maybe I won't."

With the outcome of the election a source of relative indifference to him, he's less interested in communicating with people in swing states than with people abroad. "I want to send a message to someone in Iraq, in China, in Afghanistan," that there are people in America who oppose Bush's foreign policy, he says.

Many liberals find such sentiments so irrational as to make discussion impossible. "I don't know: How do you convince the potential rioters that they're buying Christmas presents for Karl Rove?" Gitlin says.

No one's come up with any good answers. Instead, a few liberal organizers are hoping to create alternatives that could channel some of the city's anti-Bush energy away from confrontation. Chief among them is Glaser, an urbane, eloquent man who seems to adore New York and despise George Bush with equal fervor.

Since Glaser sees the problem of protest violence as a semiotic one, he's tried to find a design solution. To that end, he's working on a project called Light Up the Sky, which he calls a "manifestation that clearly says we are opposed to Bush's principles and policies. It's a powerful and peaceful response to what the Bush administration has done."

He's made fliers and a Web site describing the idea. "On Aug. 30, from dusk to dawn, all citizens who wish to end the Bush presidency can use light as our metaphor," it says. "We can gather informally all over the city with candles, flashlights and plastic wands to silently express our sorrow over all the innocent deaths the war has caused. We can gather in groups or march in silence. No confrontation and, above all, no violence. Violence will only convince the undecided electorate to vote for Bush. Not a word needs to be spoken. The entire world will understand our message. Those of us who live here in rooms with windows on the street can keep our lights on through the night. Imagine, it's 2 or 3 in the morning and our city is ablaze with a silent and overwhelming rebuke ... Light transforms darkness."

He envisions something far more expansive than a candlelight vigil. "This city is full of invention," he says, and he hopes people will use some of it to make light sculptures, light suits, all kinds of incandescent constructions. Thus illuminated, he images New Yorkers coming together all over the city, in its parks and avenues and promenades.

Light Up the Sky, he knows, is not going to dissuade those determined to wreak havoc. "There's always a factor of people who need violence. They need to overthrow their father. It gets them into the center of attention," he says. But much of the confrontation between police and protesters is built into the current situation. "People can't go to Central Park. They're marginalized at the edge of the city. It's getting to be a mess," he says. "It's pre-scripted. What you have to do is abort the script." Otherwise, he fears, the consequences could be even more calamitous than they were in 1968. "The revolution will not come," he says, wryly dismissing the grandiose hopes of some anarchists. "What they might do is ensure the election of Bush. I don't think the country can survive another four years of Bush. It's been horrible so far. It's taken us far away from my vision of America."

At 75, Glaser fears he'll never see that vision of America again. "I would hate to die," he says, "with Bush in power."

Shares