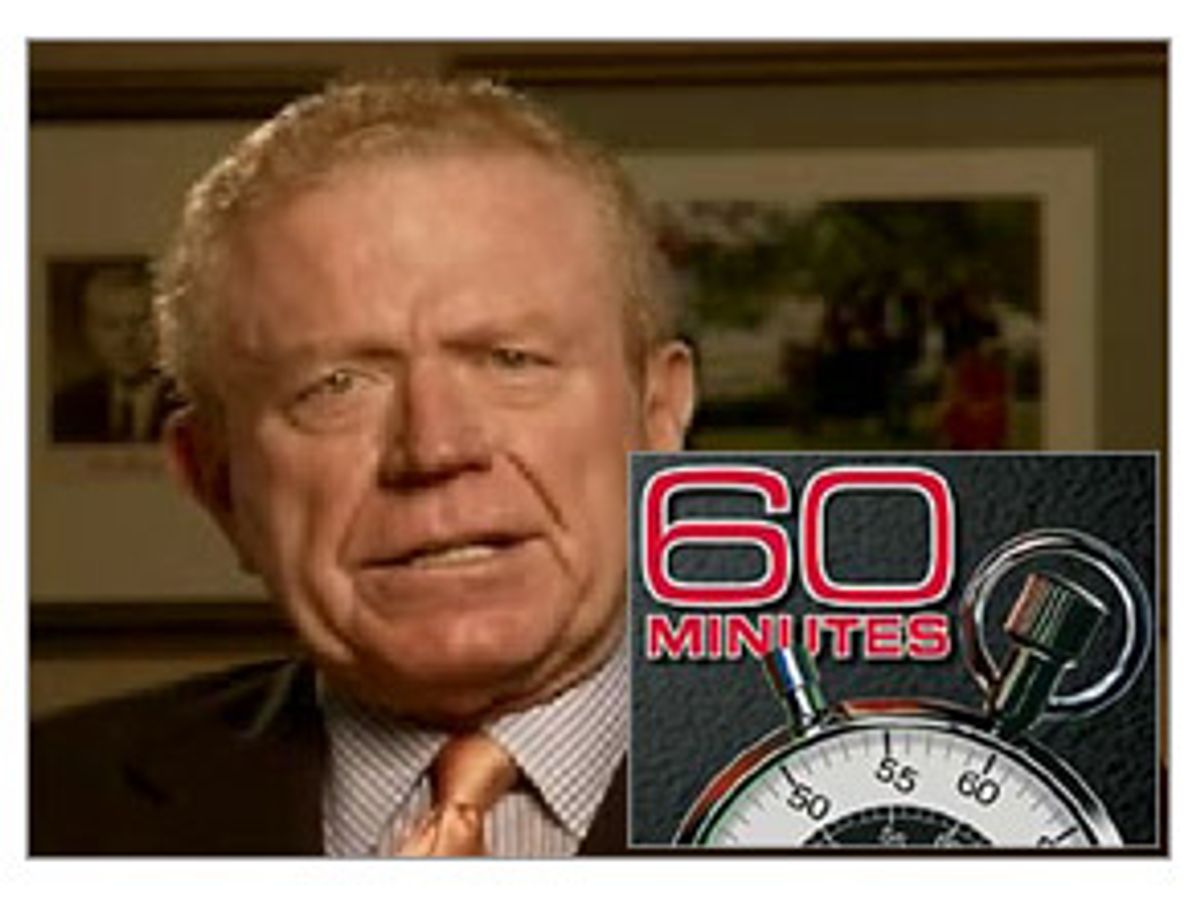

The campaign battle over Vietnam War records is still raging, but President Bush may soon be the one answering uncomfortable questions about his past service. Ben Barnes, the former lieutenant governor of Texas, will finally break his silence and talk to the press about what role he played in helping Bush get a coveted slot in the Texas Air National Guard in 1968. Sources say Barnes has already sat down for a "60 Minutes" interview that will air next week. A "60 Minutes" spokesperson declined to comment, saying the program does not discuss reports that are in progress.

Barnes made headlines last week when his videotaped comments that he was "very ashamed" of getting Bush into the National Guard began circulating on the Web. He said the remorse was prompted by a recent visit to the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, where he saw the names of thousands of other young men who did not enjoy the connections of the Bush family. Barnes made his comments in May and the video was posted on a pro-Kerry Web site in June, but word of it only began to spread widely last Friday.

Over the weekend, the national press, which for weeks has been amplifying factually challenged allegations against John Kerry by the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, gave Barnes' stunning remarks only cursory coverage. The Washington Post, for instance, ran a brief wire story on Saturday, the same day it printed yet another exhaustive piece about allegations surrounding Kerry's war past. In a subsequent WashingtonPost.com online chat, the Post reporter covering the Swift boat story suggested Barnes' comments didn't qualify as "fresh information," and consequently he wasn't interested in "simply regurgitating old controversies." The New York Times ran a brief item on Barnes' statements deep inside its Saturday news section, next to yet another lengthy profile of Kerry's longtime Swift boat nemesis, John O'Neill.

With Barnes now being featured in a sit-down interview with "60 Minutes," the highly rated CBS news magazine, reporters may finally be forced to address the consistent curiosities of Bush's National Guard record. Such as why, after nearly a decade of sifting through military records, neither Bush nor his team of longtime advisors can piece together a coherent explanation for his whereabouts, particularly after April 1972 when Bush inexplicably stopped flying and moved to Alabama, failed to take his physical exam, was grounded by his superiors, and by all accounts failed to show up for weekend training for months at a time. Bush received an honorable discharge in 1973 in order to attend Harvard Business School. Bush supporters insist the honorable discharge proves his service was above reproach. But military legal experts note honorable discharges, particularly in the early '70s as the Vietnam War was winding down, do not indicate unblemished military records.

Rather than offering insight into Bush's so-called missing year, Barnes has firsthand knowledge of how Bush was able to get into the Guard. During the Vietnam War, Guard members were rarely called up for duty in Vietnam, making it a top choice among those seeking to avoid serving in wartorn Southeast Asia. (On his Air Force pilot application, when asked about an overseas assignment, Bush checked "do not volunteer.") In fact, Bush's Guard unit was known as the Champagne Unit, because among its members were sons of prominent Texas politicians and businessmen.

Throughout his political career Bush has adamantly denied that he got a Guard pilot spot through preferential treatment. That, despite the fact Bush was jumped ahead of a nationwide waiting list of 100,000 Guard applicants, while achieving the lowest possible passing grade on his pilot aptitude test for would-be fliers, and listing "none" as his background qualifications.

Barnes, once a rising star in Texas politics, insists strings were pulled on Bush's behalf, and he helped pull them. Speaking to Kerry supporters in Austin, Texas, in May, he said, "I got a young man named George W. Bush into the Texas National Guard ... I got a lot of other people in the National Guard because I thought that was what people should do when you're in office, and you help a lot of rich people." Recalling a recent visit to the Vietnam Memorial, Barnes added, "I looked at the names of the people that died in Vietnam, and I became more ashamed of myself than I have ever been, because it was the worst thing I ever did, was help a lot of wealthy supporters and a lot of people who had family names of importance get into the National Guard. And I'm very sorry about that, and I'm very ashamed."

That story is entirely consistent with the statement Barnes made five years ago, when he revealed that in 1968 he made the phone call to the head of the Texas Air National Guard at the request of the late Sidney Adger, a Houston oil man and longtime Bush family friend. At the time, neither Bush nor his campaign directly denied the story. Bush simply stressed that neither he nor his father had made a call on his behalf, and he was unaware of any other such string pulling.

"Ben Barnes is a key to this election because he knows firsthand what happened in 1968," says Paul Alexander, director of "Brothers in Arms," a new pro-Kerry documentary about the Democratic candidate's Vietnam experience. Alexander has also written extensively about Bush's past. "Barnes is an eyewitness."

Barnes is a Kerry supporter, and the White House last week tried to depict him as a longtime partisan. But the fact is, Barnes for years resisted any attempt to get dragged into a political debate about Bush's war record. It was only under threat of legal action back in 1999 -- and only after efforts to assert "executive privilege" failed -- that Barnes came forward with his statement about helping Bush. (And even then, Barnes issued it through his attorney, refusing to answer press questions.) The lawsuit was brought by a disgruntled Texas lottery executive who charged that his former company, which Barnes lobbied for, was able to keep a lucrative Texas state contract in exchange for Barnes' remaining silent about helping Bush get into the Guard. The case was later settled out of court, with the executive receiving $300,000.

In 1998 Barnes even met privately with Bush's then-campaign manager and current commerce secretary, Donald Evans, in order to give him a heads up about the unfolding Guard story. Bush himself sent Barnes a note thanking him "for his candor" on the matter.

Whether Bush still appreciates Barnes' "candor" next week remains to be seen.

Shares