Philadelphia's 2003 mayoral election did not set especially high standards for civic discourse in the city where American democracy was born. Talking to Philadelphians about the bitter contest between John Street, the African-American incumbent Democrat, and Sam Katz, the white Republican challenger, is like discussing an election in some upstart Latin American democracy. During the course of the race, Street's office was bugged by the FBI, a Katz field office was "firebombed" by an unlit Molotov cocktail, and on Election Day, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, 84 voting-related incidents were called in to police, including "assaults, disturbances, threats, harassment, vandalism" and one bona fide "polling-place brawl."

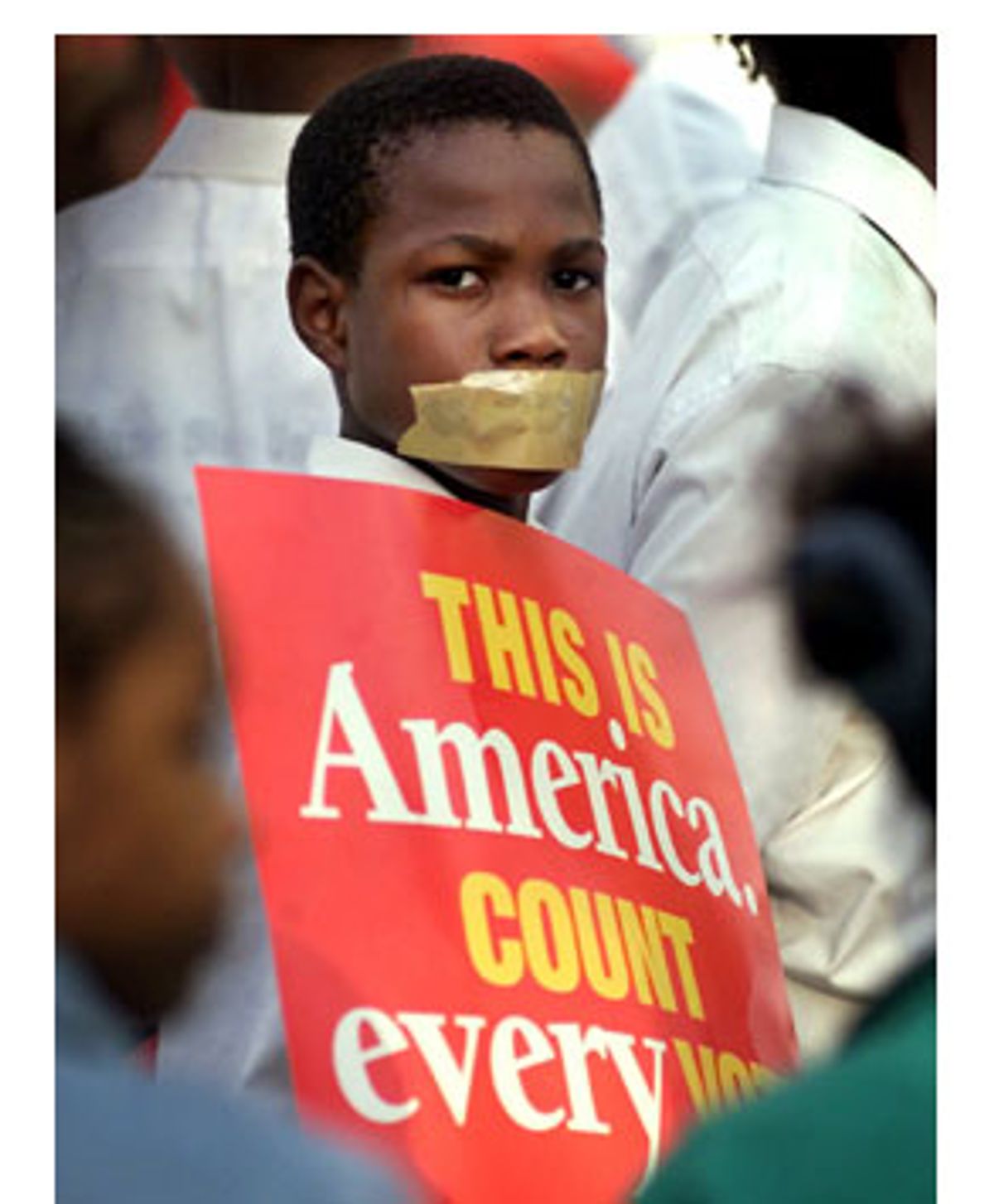

Amid the general ugliness of the race, though, there's one incident that Democrats in the city remember with a distinct sense of unease. The story, which was first reported by The American Prospect in February, and has since been broadcast by activist groups like MoveOn.org, goes like this: In an attempt to intimidate African-Americans and deter them from showing up at the polls, the Katz campaign, or one of its associates, put together a team of men dressed in official-looking attire -- dark suits, lapel pins bearing insignia of federal or local law-enforcement agencies -- and sent them into areas of the city with large black populations. According to Sherry Swirsky, a local antitrust attorney who is active in Democratic politics and who worked as an election monitor that day, the men carried clipboards and drove around in unmarked black vans.

"Some of them were just driving around neighborhoods, looking menacing," Swirsky recalls. "But others were going up to voters and giving them misinformation about the kind of I.D. they needed in order to vote. The truth is, you don't need any I.D. to vote. But they were telling them they needed a major credit card, a passport or driver's license. They were telling them it was risky to vote if they had any outstanding child support bills. Imagine the menacing presence of a bunch of big white guys in black cars who look like they're law-enforcement people telling you all these things."

Swirsky has monitored several elections in Philadelphia and elsewhere and headed the Democrats' presidential recount effort in New Mexico in 2000. But what happened in Philadelphia, she says, is the most sophisticated election intimidation campaign she's ever seen. It was not a sick prank by one or two racists but instead a systematic effort that required planning and not-insignificant outlays of money (the uniforms, the vehicles and the men, some of whom were reportedly recruited from out of state). "There was such a level of coordination there that if its objectives were not improper, I would say I admired it for the professionalism," she says.

Swirsky met dozens of voters who were intimidated by strange men in uniforms; in a survey of black voters taken after the election, 7 percent reported being accosted by voter-intimidation efforts. "I talked to a number of them and tried to assuage their concerns," she says. "I told them they should go out and vote: 'Those people were wrong. You don't need that kind of identification. No, you're not going to get arrested if you owe child support and you go out to vote.'" But despite her efforts -- and even though, in the end, Street won the race -- Swirsky is certain that many black voters stayed away from the polls that day.

The voter-intimidation campaign that Republicans mounted in Philadelphia was not an anomaly. Instead, it marked a routine occurrence in American elections, a national scandal that rarely makes the front page. The sad fact is that voter-intimidation efforts aimed at minorities have been carried out in just about every major election over the past 20 years. The campaigns are almost always mounted by Republicans who aim to reduce the turnout of overwhelmingly Democratic minority voters at the polls. Now, in what's shaping up to be a razor-thin presidential election, Democrats across the country are pointing to what occurred in Philadelphia as an example of what they have to fear from Republicans this election year.

To Americans today, the idea that a major political party actively plans to disenfranchise minority voters may seem anachronistic; we'd like to believe that such tactics would no longer be tolerated in our nation. But over the last two decades, various arms of the Republican Party, or groups working for Republican candidates -- at the national, state and local levels -- have carried out well-documented projects designed to intimidate blacks and other minorities.

Under the guise of "ballot security" measures, supposedly designed to preserve an election's "integrity" and reduce "voter fraud," Republicans have organized off-duty cops to patrol heavily minority precincts, put up threatening signs, and mailed out sternly worded "bulletins" warning of the consequences of voter fraud. They've also systematically challenged the residency of thousands of minority voters in several elections, and they've rigged voter rolls to exclude minorities eligible to vote, which occurred in Florida in 2000. These were not ad hoc efforts. As in Philadelphia's mayor's race, they were often planned and executed for the specific purpose of reducing black turnout in order to boost Republican political fortunes.

The Republican Party denies any plans to suppress the minority vote this year; in fact, President Bush has recently attempted to court black voters. Swirsky and other Democrats who fear that the GOP may attempt to suppress the black vote can produce no proof that Republicans are up to no good. But many independent observers are suspicious. "As we look at the last 12 months or so, we are extremely concerned about incidents indicating that Republican officials may be planning to challenge minority voters," says Ralph Neas, president of the nonpartisan People for the American Way Foundation.

Neas is referring not just to the Philadelphia mayor's race but also to a widely publicized absentee ballot-fraud investigation conducted by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement in Orlando this summer. In that investigation, elderly African-American voters were visited at their homes by police officers curious about their voting behavior. While Florida officials deny any attempt to intimidate voters, critics say the investigation is emblematic of the kind of under-the-radar, state-sponsored intimidation program that Republican officials have conducted in the past. On Friday, the Justice Department disclosed that it has initiated a civil rights investigation into what occurred in Orlando.

Currently the NAACP, People for the American Way Foundation, Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and other voting-rights groups are putting together what they call a historic effort to forestall voter-intimidation tactics this year. In the days before the vote and on Election Day itself, these groups will send an armada of lawyers to polling places across 17 states to watch for and react to any legal challenges that come up -- an attempt to derail the most outrageous intimidation campaigns.

Many black voters themselves are intensely aware of the prospect of suppression tactics -- and they're ready for them, says Julian Bond, chairman of the NAACP. "This is part of the folklore of black America, especially since 2000," he says. "Many people have tales to tell about this happening to people they know."

Still, despite the counter-intimidation efforts and increased awareness, elections experts still predict that suppression programs will likely succeed in turning away many voters at the polls this year. How many? Hundreds, thousands, millions? Nobody knows. But Bond notes that it took less than 600 votes in Florida to swing the election to Bush last time, and he believes that more than 600 African-American Gore voters were disenfranchised there. If this year's "election is as close as everyone believes it will be," Bond says, "and if they frighten just 600 voters away from the polls," minority voter-intimidation tactics may very well determine the next president of the United States.

In July, John Pappageorge, a Republican state representative in Troy, Mich., attended a local party meeting to discuss with colleagues the Republicans' chances of winning the state for Bush in November. In the course of the discussion, according to an account published in the Detroit Free Press, Pappageorge declared, "If we do not suppress the Detroit vote, we're going to have a tough time in this election." Detroit, of course, has a huge minority population; about 83 percent of its residents are African-American. Pappageorge's statement was roundly condemned and he quickly apologized for it, insisting that he wasn't suggesting anything racist or illegal in calling for a suppression of the Detroit vote. As a matter of politic strategy, Pappageorge was probably right.

A concise political axiom underlies the Republican rationale for mounting voter-suppression campaigns aimed at blacks: African-Americans don't vote for Republicans. In the 2000 election, Bush received about 9 percent of the black vote and nobody believes he has a chance of improving on that this year. His father received about the same percentage of the African-American vote, as did Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon.

It's true that despite those consistently low numbers, Republican presidential candidates sometimes make a play for African-American voters, as Bush recently did in his much-heralded speech to the Urban League. But these efforts are obviously disingenuous, Democrats contend, because the last thing a Republican candidate would want is more people from an overwhelmingly Democratic demographic coming to the polls. The likelier reason that Republicans occasionally attempt to woo black voters is as a way of signaling to whites that they're compassionate.

Indeed, strategists say, both the Republicans' and Democrats' efforts to win black voters rarely have anything to do with specific policies that might be of importance to African-Americans. Since Democratic presidents and governors usually can't win without huge African-American turnouts, and since Republicans can't win with such turnouts, each party's approach to African-American voters is at best a numbers game. Democrats are forever working on methods to increase the minority turnout, while Republicans try to keep as many minorities at home as possible on Election Day. That is not a scurrilous charge against the GOP, though it sounds like one; it's the way politics is practiced in America.

At least it's the way politics has been practiced since the early 1980s, when Republicans first began implementing their most brazen voter-intimidation campaigns. In the 1981 New Jersey gubernatorial election, the RNC and its affiliates devised a program that they claimed was aimed at reducing voter fraud. The party hired police officers to patrol minority neighborhoods in Passaic County and put up signs warning that the election was being monitored "by the Ballot Security Task Force." The plan was obviously meant to intimidate voters rather than secure the polls. When Democrats filed a civil rights lawsuit against the Republicans over the tactics, the national GOP and the New Jersey Republicans were forced to sign a consent decree promising to refrain from the sorts of suppression activities they employed in the 1981 race. (The election, incidentally, was won by the Republican candidate, Thomas Kean, who later went on to chair the commission investigating the 9/11 attacks.)

But the pull of voter intimidation was too strong for the Republicans, the math of suppression irresistible. In 1986 the party hired an outside company to conduct another ballot-security initiative, this one aimed at challenging the voting eligibility of 31,000 voters in Louisiana, the vast majority of whom were black. According to a 2002 study of voter-intimidation practices that Swirsky wrote for the Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review, when Democrats again sued over the ballot-security initiative, they unearthed a Republican planning document that stated that the Louisiana program "could keep the African-American vote down considerably."

In 1987, because of that evidence, the RNC was once again forced to enter into an agreement with Democrats, this one requiring the federal courts to preapprove all of the Republicans' ballot-security programs. But as Swirsky reports in her study, even this order "did not end Republican efforts to depress minority voter turnout."

In the 1990 Senate contest between Jesse Helms and Harvey Gannt in North Carolina, the state Republican Party mailed out "voter registration bulletins" to 150,000 homes in minority precincts, warning that voters would need to bring a raft of personal information to the polls on Election Day, and adding, falsely, that a voter "must have lived in [a] precinct for at least the previous 30 days" to be eligible to vote there. The mailings also warned of penalties for providing inaccurate information to elections officials. The Justice Department later brought a legal challenge against the state party over the mailings and Republicans agreed, once again, to curtail their efforts to suppress minority-voter turnout.

You can guess what the Republicans did after that -- more of the same. In August, the People for the American Way Foundation and the NAACP released a report detailing the past two decades' sorry history of voter-intimidation efforts. The report reads like a chronicle of the Jim Crow South, except the dates are in the 1980s and 1990s, and the locations are not limited to points below the Mason-Dixon line.

In 1988 in Hidalgo County, Texas, the Republican Party ran ads targeted at Latino voters. They warned of prison sentences for non-U.S. citizens who go to the polls, adding that officials "will be watching." In South Dakota in 2002, the state attorney general devised an anti-voting-fraud plan that involved sending law-enforcement officials to question 2,000 newly registered Native American voters. There was no similar probe, the report notes, "to investigate new registrants in counties without significant Native American populations, despite the fact that those counties contained most of the new registrations in the state."

In Dillon County, S.C., in 1998, Son Kinon, a Republican state official, mailed out 3,000 brochures to black voters warning, "You have always been my friend, so don't chance GOING TO JAIL on Election Day! ... SLED [South Carolina Law Enforcement Division] agents, FBI agents, people from the Justice Department and undercover agents will be in Dillon County working this election. People who you think are your friends, and even your neighbors, could be the very ones that turn you in. THIS ELECTION IS NOT WORTH GOING TO JAIL!!!!!!"

To many African-Americans, the most notorious effort to disenfranchise blacks occurred in Florida in 2000. During the election, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Republican state officials "failed to fulfill their responsibilities." In the aftermath of the debacle, numerous media reports surfaced of organized efforts to keep blacks away from the polls -- tales of police roadblocks erected in black neighborhoods, of election officials asking voters for unnecessary identification, of people being forcibly turned away from the polls by police. A few of these stories were discredited. Yet when the commission investigated the election, it corroborated many of them.

Floridians told the commission that they saw police cars illegally patrolling areas near polling places. They testified that in minority neighborhoods, polling places were closed early or were moved without any notice. The commission declared that election problems in Florida resulted "in an extraordinarily high and inexcusable level of disenfranchisement, with a significantly disproportionate impact on African American voters."

Much of the disenfranchisement was caused by antiquated voting machines used in minority neighborhoods; while just 11 percent of Florida's voters are African-American, more than half of the spoiled ballots -- more than 90,000 of the votes tossed out -- were cast by blacks. But another major source of disenfranchisement was the state's erroneous purging from voter rolls of thousands of suspected felons, the vast majority of whom were African-Americans. The purging occurred, the commission concluded, as a result of the "overzealous" efforts of Gov. Jeb Bush and Secretary of State Katherine Harris to combat voter fraud. "African American voters were placed on purge lists more often and more erroneously than Hispanic or white voters," the commission also noted. Could it be, many Democrats wonder, that Hispanic voters were not purged because, at least in Florida, they tend to vote Republican?

Year after year, race after race, Republicans have launched efforts to deter minorities from the polls. Yet they have suffered few legal or political costs stemming from the shameful practices. Why? Part of the reason, voting-rights activists say, is it's very difficult to prove the connections between specific vote-suppression tactics and the candidates who've apparently launched them. The candidates and campaigns who plan these efforts often hire third-party consultants to take care of the dirty work, so plausible deniability can always be maintained. Moreover, when Republicans are caught trying to suppress the vote, they often offer a reasonable-sounding explanation. It's all about "voting integrity," they say, an attempt to safeguard the polling place from fraud.

Just listen to Vito Canuso, a Philadelphia lawyer who is the chairman for the Republican City Committee. Told about Democrats' allegations that black voters in the 2003 mayoral race were questioned by men dressed as law-enforcement officials, Canuso categorically denies that any such effort had been pursued. "That's untrue," he says. So how might he explain why so many people had seen such men that day? "Did we have more people in the street than we've ever had before? Yes," he says. "Did we have more people backing us up than we had before? Yes. We did have a group of lawyers in the streets and I'm sure they were dressed like lawyers, and in some neighborhoods you don't see people dressed like lawyers. But we weren't going to put them in jeans and a sweatshirt. A lot of people were accusing them of being federal agents but they were lawyers."

Canuso says Republicans brought out so many lawyers because the party suspected that voters were cheating. "The number of people registered to vote almost exceeds the number of people who live in the city," he says. "We have every reason to believe that there are people with double and triple registrations on the rolls." Therefore, he says, challenging voters was necessary, and lawyers had a legal right to question anyone who appeared to be out of place at a particular precinct.

How would the lawyers make such a determination in deciding whether to challenge a voter's right to vote? Swirsky says the lawyers concentrated on minorities, with a special emphasis on people who seemed economically less well-off or appeared to be homeless. Canuso responds that the lawyers were instructed to challenge "people who seem to be out of place, who walk like they don't know where they are. This is supposed to be their neighborhood, so they should look like they know what they're doing."

Some conservative scholars have singled Philadelphia out as one of the cities with a curiously large number of registered voters, approaching or exceeding the number of eligible voters in the state. But this is a problem in many parts of the country, even in places where there are few minority voters. Some entire states -- Montana and Alaska, for instance, states not known for large African-American populations -- have more registered voters on their rolls than voting-age residents who live in the state. The phenomenon is most likely due to poor registration maintenance procedures, not active fraud on the part of voters, experts say. Moreover, if fraud existed in Philadelphia, there is no evidence to indicate that black voters should have been the ones most often challenged.

The idea that minorities at polling places should be scrutinized for vote fraud is "based on at least one racist assumption, and that is that black people cheat," says Bond of the NAACP. "I have never seen these tactics applied to whites. I've never seen them used in a partisan way by white Republicans against white Democrats. They are applied only against racial minorities. And although they may not be illegal, they are disgraceful. They are calculated to frighten and intimidate -- and for them to argue that this is simply hard-knuckled partisan politics is disingenuous in the extreme."

The Republican Party's Canuso maintains that he can't see why anyone would be intimidated by such tactics at polling places. "I only vote once, and if somebody wanted to challenge my vote, I'm willing to defend my right to vote," he says. "Why does someone else get intimidated? When I go to vote, I make sure I am properly prepared for anybody that will question my right to vote. It shouldn't intimidate them if they know they have every right to vote."

That's not the same thing, Swirsky says. Canuso is a lawyer and a man of not a small measure of clout in his city; of course he wouldn't be intimidated if someone came up to him and challenged his right to vote. But that doesn't stand up "when you're dealing with a culture that has a long history of disenfranchisement," she says.

For many blacks in America, voting is still a tenuous, fragile right, one exercised with as much fear as pride. "People often ask me, Why don't the Democrats retaliate in the suburbs?" Swirsky says. "The answer is obvious -- it's a bit difficult to intimidate a white middle-class or affluent population in the same way you can intimidate a minority population. In these areas, there is a fear of authority figures, there is a fear of any official communication." These fears are not irrational. And they are easily exploited.

In a speech to members of Congressional Black Caucus Foundation on Sept. 11, John Kerry briefly addressed minority voters' fears about possible voting irregularities this year. "We are hearing the same things you are hearing," Kerry said. "What they did in Florida in 2000, they may be planning to do in battleground states all across this country this year. Well, we are here to let them know that we will fight tooth and nail to make sure that this time, every vote is counted and every vote counts."

The Kerry campaign did not respond to several requests to discuss the problem of minority voter intimidation; neither did the Bush campaign. But Tony Welch, a spokesman for the Democratic National Committee, says that Democrats are concerned that Republicans may be planning to suppress the minority vote. He says that the party will launch a comprehensive vote-monitoring effort to combat the problem on Election Day.

There's no evidence that Republicans plan any sort of voter-suppression campaign this year, but proof rarely surfaces before Election Day. Given what's happened in previous elections, Democrats are wise to be wary. When asked about the issue, Christine Iverson, a spokeswoman for the Republican National Committee, says Republicans have devised a specific plan to combat minority voter intimidation at the polls this year. The plan, though, is bipartisan, meaning that it won't go forward until both parties agree to it.

Specifically, the RNC plan calls for both Republicans and Democrats to each choose precincts around the country that they believe are susceptible to problems, and then for each party to send representatives to every precinct on the list. These monitors will work together in a bipartisan fashion, Iverson says, to ensure a fair election. "We say that if the Democrats truly believed their own charges," she says, "they would jump at the chance to have Democrats join with Republicans to have bipartisan teams" monitoring polling places.

Ed Gillespie, chairman of the RNC, outlined this plan in a letter he recently sent to Terry McAuliffe, the DNC's chairman. But the Democrats rejected Gillespie's offer; they say that they won't join with the Republicans. "We don't trust them," Welch says, explaining that he doesn't believe that Republicans really want to ensure that minority voters get to the polls. In the meantime, the DNC will monitor the program independently of Republicans. "Theirs was a gimmick," Welch says. "They sent a letter, and they haven't done anything since. Here's the test: What will they do now? Will they complain that their letter wasn't taken seriously or will they spend time and money to make sure that African-Americans can vote in Florida? They've got 45 days left."

It's unlikely that the Republicans will take up the challenge; the party has no reason to spend money to launch a program designed to make sure that African-Americans vote on Election Day. But will the Republican Party at least renounce any efforts to suppress the minority vote in November? Bond of the NAACP has publicly challenged the party to do so, and it has not responded.

Of particular interest to some Democrats is whether John Ashcroft's Justice Department will act to protect minorities if irregularities are discovered on Election Day. One reason election monitors worry that 2004 will be a particularly bad year for voter suppression is that the federal legal atmosphere has been dramatically altered since the last presidential election -- and not for the better.

In 2002, in response to the problems uncovered in the 2000 election, President Bush signed the Help America Vote Act, which many lawmakers had hoped would reduce incidents of voter suppression. But HAVA, as it is known, could actually make the polling experience more difficult for many voters. Swirsky says it outlines a new set of onerous rules concerning the kind of identification that people need to bring with them when they go to the polls. In this week's New Yorker magazine, Jeffrey Toobin reports that the Justice Department has interpreted HAVA to mean that states should "verify" the Social Security numbers people submit when they mail in their registration forms. In other words, the Justice Department wants first-time voters to come to the polls with a driver's license or a Social Security card in order to vote, a requirement that voting-rights activists believe will turn off minority voters.

The Justice Department's I.D. requirement is in keeping with Republican sensibilities toward voting law. The party is generally more in favor of protecting against vote fraud than intent on prosecuting voter suppression and intimidation tactics. Ashcroft in particular would seem to be a poor guardian of minorities' voting rights. As was revealed during his contentious confirmation hearings, the attorney general has in the past opposed school desegregation efforts and has expressed sympathy and admiration for the Confederacy. "We've seen a lack of federal enforcement" on laws to protect voters' rights, says Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr., an Illinois Democrat. "It's almost as if the Ashcroft Justice Department has ignored the history of voter intimidation. They have sanctioned voter terrorism."

But this state of affairs may also have its benefits. Since Bush's election, African-American voters have come to understand, once again, the fragility of their vote, and they are ready, once again, to fight. "They are very much aware of what happened in 2000 -- there's not one black person in America that's not aware of what happened in Florida," says Donna Brazile, Al Gore's former campaign manager and the head of the DNC's Voting Rights Institute.

Black voters are angry, Brazile says. They are angry about their disenfranchisement and perhaps that alone will bring them to the polls this year. But there's a lot more that African-American voters have to seethe over, and Republican intimidation campaigns may not be able to hold them back. "They're angry over the loss of jobs," Brazile says. "They're angry over slipping back into poverty. They're angry over the misguided war in Iraq. There's enough anger to go around in the black community for a long time."

Shares