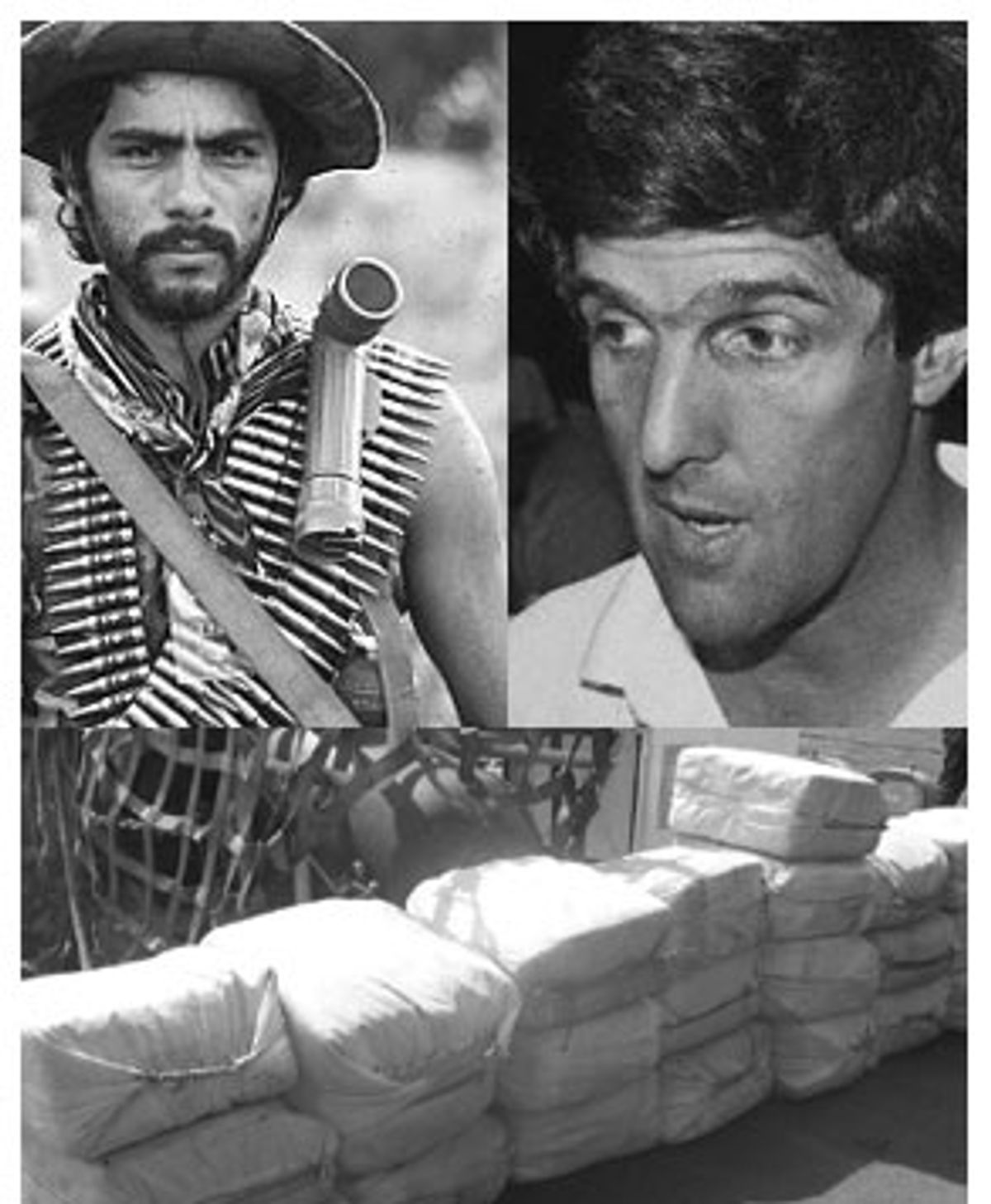

In December 1985, when Brian Barger and I wrote a groundbreaking story for the Associated Press about Nicaraguan Contra rebels smuggling cocaine into the United States, one U.S. senator put his political career on the line to follow up on our disturbing findings. His name was John Kerry.

Yet, over the past year, even as Kerry's heroism as a young Navy officer in Vietnam has become a point of controversy, this act of political courage by a freshman senator has gone virtually unmentioned, even though -- or perhaps because -- it marked Kerry's first challenge to the Bush family.

In early 1986, the 42-year-old Massachusetts Democrat stood almost alone in the U.S. Senate demanding answers about the emerging evidence that CIA-backed Contras were filling their coffers by collaborating with drug traffickers then flooding U.S. borders with cocaine from South America.

Kerry assigned members of his personal Senate staff to pursue the allegations. He also persuaded the Republican majority on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to request information from the Reagan-Bush administration about the alleged Contra drug traffickers.

In taking on the inquiry, Kerry challenged President Ronald Reagan at the height of his power, at a time he was calling the Contras the "moral equals of the Founding Fathers." Kerry's questions represented a particular embarrassment to Vice President George H.W. Bush, whose responsibilities included overseeing U.S. drug-interdiction policies.

Kerry took on the investigation though he didn't have much support within his own party. By 1986, congressional Democrats had little stomach left for challenging the Reagan-Bush Contra war. Not only had Reagan won a historic landslide in 1984, amassing a record 54 million votes, but his conservative allies were targeting individual Democrats viewed as critical of the Contras fighting to oust Nicaragua's leftist Sandinista government. Most Washington journalists were backing off, too, for fear of getting labeled "Sandinista apologists" or worse.

Kerry's probe infuriated Reagan's White House, which was pushing Congress to restore military funding for the Contras. Some in the administration also saw Kerry's investigation as a threat to the secrecy surrounding the Contra supply operation, which was being run illegally by White House aide Oliver North and members of Bush's vice presidential staff.

Through most of 1986, Kerry's staff inquiry advanced against withering political fire. His investigators interviewed witnesses in Washington, contacted Contra sources in Miami and Costa Rica, and tried to make sense of sometimes convoluted stories of intrigue from the shadowy worlds of covert warfare and the drug trade.

Kerry's chief Senate staff investigators were Ron Rosenblith, Jonathan Winer and Dick McCall. Rosenblith, a Massachusetts political strategist from Kerry's victorious 1984 campaign, braved both political and personal risks as he traveled to Central America for face-to-face meetings with witnesses. Winer, a lawyer also from Massachusetts, charted the inquiry's legal framework and mastered its complex details. McCall, an experienced congressional staffer, brought Capitol Hill savvy to the investigation.

Behind it all was Kerry, who combined a prosecutor's sense for sniffing out criminality and a politician's instinct for pushing the limits. The Kerry whom I met during this period was a complex man who balanced a rebellious idealism with a determination not to burn his bridges to the political establishment.

The Reagan administration did everything it could to thwart Kerry's investigation, including attempting to discredit witnesses, stonewalling the Senate when it requested evidence and assigning the CIA to monitor Kerry's probe. But it couldn't stop Kerry and his investigators from discovering the explosive truth: that the Contra war was permeated with drug traffickers who gave the Contras money, weapons and equipment in exchange for help in smuggling cocaine into the United States. Even more damningly, Kerry found that U.S. government agencies knew about the Contra-drug connection, but turned a blind eye to the evidence in order to avoid undermining a top Reagan-Bush foreign policy initiative.

The Reagan administration's tolerance and protection of this dark underbelly of the Contra war represented one of the most sordid scandals in the history of U.S. foreign policy. Yet when Kerry's bombshell findings were released in 1989, they were greeted by the mainstream press with disdain and disinterest. The New York Times, which had long denigrated the Contra-drug allegations, buried the story of Kerry's report on its inside pages, as did the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times. For his tireless efforts, Kerry earned a reputation as a reckless investigator. Newsweek's Conventional Wisdom Watch dubbed Kerry a "randy conspiracy buff."

But almost a decade later, in 1998, Kerry's trailblazing investigation was vindicated by the CIA's own inspector general, who found that scores of Contra operatives were implicated in the cocaine trade and that U.S. agencies had looked the other way rather than reveal information that could have embarrassed the Reagan-Bush administration.

Even after the CIA's admissions, the national press corps never fully corrected its earlier dismissive treatment. That would have meant the New York Times and other leading publications admitting they had bungled their coverage of one of the worst scandals of the Reagan-Bush era.

The warm and fuzzy glow that surrounded Ronald Reagan after he left office also discouraged clarification of the historical record. Taking a clear-eyed look at crimes inside Reagan's Central American policies would have required a tough reassessment of the 40th president, which to this day the media has been unwilling to do. So this formative period of Kerry's political evolution has remained nearly unknown to the American electorate.

Two decades later, it's hard to recall the intensity of the administration's support for the Contras. They were hailed as courageous front-line fighters, like the Mujahedin in Afghanistan, defending the free world from the Soviet empire. Reagan famously warned that Nicaragua was only "two days' driving time from Harlingen, Texas."

Yet, for years, Contra units had gone on bloody rampages through Nicaraguan border towns, raping women, torturing captives and executing civilian officials of the Sandinista government. In private, Reagan referred to the Contras as "vandals," according to Duane Clarridge, the CIA officer in charge of the operation, in his memoir, "A Spy for All Seasons." But in public, the Reagan administration attacked anyone who pointed out the Contras' corruption and brutality.

The Contras also proved militarily inept, causing the CIA to intervene directly and engage in warlike acts, such as mining Nicaragua's harbors. In 1984, these controversies caused the Congress to forbid U.S. military assistance to the Contras -- the Boland Amendment -- forcing the rebels to search for new funding sources.

Drug money became the easiest way to fill the depleted Contra coffers. The documentary evidence is now irrefutable that a number of Contra units both in Costa Rica and Honduras opened or deepened ties to Colombian cartels and other regional drug traffickers. The White House also scrambled to find other ways to keep the Contras afloat, turning to third countries, such as Saudi Arabia, and eventually to profits from clandestine arms sales to Iran.

The secrets began to seep out in the mid-1980s. In June 1985, as a reporter for the Associated Press, I wrote the first story mentioning Oliver North's secret Contra supply operation. By that fall, my AP colleague Brian Barger and I stumbled onto evidence that some of the Contras were supplementing their income by helping traffickers transship cocaine through Central America. As we dug deeper, it became clear that the drug connection implicated nearly all the major Contra organizations.

The AP published our story about the Contra-cocaine evidence on Dec. 20, 1985, describing Contra units "engaged in cocaine smuggling, using some of the profits to finance their war against Nicaragua's leftist government." The story provoked little coverage elsewhere in the U.S. national press corps. But it pricked the interest of a newly elected U.S. senator, John Kerry. A former prosecutor, Kerry also heard about Contra law violations from a Miami-based federal public defender named John Mattes, who had been assigned a case that touched on Contra gunrunning. Mattes' sister had worked for Kerry in Massachusetts.

By spring 1986, Kerry had begun a limited investigation deploying some of his personal staff in Washington. As a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Kerry managed to gain some cooperation from the panel's Republican leadership, partly because the "war on drugs" was then a major political issue. Besides looking into Contra drug trafficking, Kerry launched the first investigation into the allegations of weapons smuggling and misappropriation of U.S. government funds that were later exposed as part of North's illegal operation to supply the Contras.

Kerry's staff soon took an interest in a federal probe in Miami headed by assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Feldman. Talking to some of the same Contra supporters whom we had interviewed for the AP's Contra-cocaine story, Feldman had pieced together the outlines of North's secret network.

In a panicked memo dated April 7, 1986, one of North's Costa Rican-based private operatives, Robert Owen, warned North that prosecutor Feldman had shown Ambassador Lewis Tambs "a diagram with your name underneath and John [Hull]'s underneath mine, then a line connecting the various resistance groups in C.R. [Costa Rica]. Feldman stated they were looking at the 'big picture' and not only looking at possible violations of the Neutrality Act, but a possible unauthorized use of government funds." (For details, see my "Lost History: Contras, Cocaine, the Press and 'Project Truth.'")

John Hull was an American farmer with a ranch in Costa Rica near the Nicaraguan border. According to witnesses, Contras had used Hull's property for cocaine transshipments. (Hull was later accused of drug trafficking by Costa Rican authorities, but fled the country before facing trial. He returned to the United States.)

On April 10, 1986, Barger and I reported on the AP wire that the U.S. Attorney's office in Miami was examining allegations of Contra gunrunning and drug trafficking. The AP story rattled nerves inside the Reagan administration. On an unrelated trip to Miami, Attorney General Edwin Meese pulled U.S. Attorney Leon Kellner aside and asked about the existence of this Contra probe.

Back in Washington, other major news organizations began to sniff around the Contra-cocaine story but mostly went off in wrong directions. On May 6, 1986, the New York Times relied for a story on information from Meese's spokesman Patrick Korten, who claimed "various bits of information got referred to us. We ran them all down and didn't find anything. It comes to nothing."

But that wasn't the truth. In Miami, Feldman and FBI agents were corroborating many of the allegations. On May 14, 1986, Feldman recommended to his superiors that the evidence of Contra crimes was strong enough to justify taking the case to a grand jury. U.S. Attorney Kellner agreed, scribbling on Feldman's memo, "I concur that we have sufficient evidence to ask for a grand jury investigation."

But on May 20, less than a week later, Kellner reversed that recommendation. Without telling Feldman, Kellner rewrote the memo to state that "a grand jury investigation at this point would represent a fishing expedition with little prospect that it would bear fruit." Kellner signed Feldman's name to the mixed-metaphor memo and sent it to Washington on June 3.

The revised "Feldman" memo was then circulated to congressional Republicans and leaked to conservative media, which used it to discredit Kerry's investigation. The right-wing Washington Times denounced the probe as a wasteful political "witch hunt" in a June 12, 1986, article. "Kerry's anti-Contra efforts extensive, expensive, in vain," screamed the headline of a Washington Times article on Aug. 13, 1986.

Back in Miami, Kellner reassigned Feldman to unrelated far-flung investigations, including one to Thailand.

The altered memo was instrumental in steering Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Richard Lugar, R-Ind., away from holding hearings, Kerry's later Contra-drug report, "Law Enforcement and Foreign Policy," stated. "Material provided to the Committee by the Justice Department and distributed to members following an Executive Session June 26, 1986, wrongly suggested that the allegations that had been made were false," the Kerry report said.

Feldman later testified to the Senate that he was told in 1986 that representatives of the Justice Department, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the FBI had met "to discuss how Senator Kerry's efforts to get Lugar to hold hearings on the case could be undermined."

Mattes, the federal public defender in Miami, watched as the administration ratcheted up pressure on Kerry's investigation. "From a political point of view in May of '86, Kerry had every reason to shut down his staff investigation," Mattes said. "There was no upside for him doing it. We all felt under the gun to back off."

The Kerry that Mattes witnessed at the time was the ex-prosecutor determined to get to the bottom of serious criminal allegations even if they implicated senior government officials. "As an investigator, he had a sense it was there," said Mattes, who is now an investigative reporter for Fox News in San Diego. "Kerry was a crusader. He was the consummate outsider, doing what you expect people to do. ... At no point did he flinch."

Years later, in the National Archives, I discovered a document showing that the Central Intelligence Agency also was keeping tabs on Kerry's investigation. Alan Fiers Jr., who served as the CIA's Central American Task Force chief, told independent counsel Lawrence Walsh's Iran-Contra investigators that the AP and Feldman's investigations had attracted the hostility of the Reagan-Bush administration. Fiers said he "was also getting a dump on the Senator Kerry investigation about mercenary activity in Central America from the CIA's legislative affairs people who were monitoring it."

Negative publicity about the Contras was particularly unwelcome to the Reagan-Bush administration throughout the spring and summer 1986 as the White House battled to restore U.S. government funding to the Contras. In the politically heated atmosphere, the administration sought to smear anti-Contra witnesses cooperating with Kerry's investigation.

In a July 28 memo, initialed as read by President Reagan, North labeled onetime Contra mercenary Jack Terrell as a "terrorist threat" because of his "anti-Contra and anti-U.S. activities." North said Terrell had been cooperating "with various congressional staffs in preparing for hearings and inquiries regarding the role of U.S. government officials in illegally supporting the Nicaraguan resistance."

In August 1986, FBI and Secret Service agents hauled Terrell in for two days of polygraph examinations on suspicion that Terrell intended to assassinate President Reagan, an allegation that proved baseless. But Terrell told me later that the investigation had chilled his readiness to testify about the Contras. "It burned me up," he said. "The pressure was always there."

Beyond intimidating some witnesses, the Reagan administration systematically worked to frustrate Kerry's investigation. Years later, one of Kerry's investigators, Jack Blum, complained publicly that the Justice Department had actively obstructed the congressional probe. Blum said William Weld, who took over as assistant attorney general in charge of the criminal division in September 1986, was an "absolute stonewall" blocking the Senate's access to evidence on Contra-cocaine smuggling. "Weld put a very serious block on any effort we made to get information," Blum told the Senate Intelligence Committee a decade after the events. "There were stalls. There were refusals to talk to us, refusals to turn over data."

Weld, who later became Massachusetts governor and lost to Kerry in the 1996 Senate race, denied that he had obstructed Kerry's Contra probe. But it was clear that the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was encountering delays in getting information that had been requested by Chairman Lugar, a Republican, and Rhode Island Sen. Claiborne Pell, the ranking Democrat. At Kerry's suggestion, they had sought files on more than two dozen people linked to the Contra operations and suspected of drug trafficking.

Inside the Justice Department, senior career investigators grew concerned about the administration's failure to turn over the requested information. "I was concerned that we were not responding to what was obviously a legitimate congressional request," Mark Richard, one of Weld's top deputies, testified in a deposition. "We were not refusing to respond in giving explanations or justifications for it. We were seemingly just stonewalling what was a continuing barrage of requests for information. That concerned me no end."

On Sept. 26, 1986, Kerry tried to spur action by presenting Weld with an 11-page "proffer" statement from a 31-year-old FBI informant who had worked with the Medellin cartel and had become a witness on cartel activities. The woman, Wanda Palacio, had approached Kerry with an account about Colombian cocaine kingpin Jorge Ochoa bragging about payments he had made to the Nicaraguan Contras.

As part of this Contra connection, Palacio said pilots for a CIA-connected airline, Southern Air Transport, were flying cocaine out of Barranquilla, Colombia. She said she had witnessed two such flights, one in 1983 and the other in October 1985, and quoted Ochoa saying the flights were part of an arrangement to exchange "drugs for guns."

According to contemporaneous notes of this "proffer" meeting between Weld and Kerry, Weld chuckled that he was not surprised at allegations about corrupt dealings by "bum agents, former and current CIA agents." He promised to give serious consideration to Palacio's allegations.

After Kerry left Weld's office, however, the Justice Department seemed to concentrate on poking holes in Palacio's account, not trying to corroborate it. Though Palacio had been considered credible in her earlier testimony to the FBI, she was judged to lack credibility when she made accusations about the Contras and the CIA.

On Oct. 3, 1986, Weld's office told Kerry that it was rejecting Palacio as a witness on the grounds that there were some contradictions in her testimony. The discrepancies apparently related to such minor points as which month she had first talked with the FBI.

Two days after Weld rejected Palacio's Contra-cocaine testimony, other secrets about the White House's covert Contra support operations suddenly crashed --literally -- into view.

On Oct. 5, a quiet Sunday morning, an aging C-123 cargo plane rumbled over the skies of Nicaragua preparing to drop AK-47 rifles and other equipment to Contra units in the jungle below. Since the Reagan administration had recently won congressional approval for renewed CIA military aid to the Contras, the flight was to be one of the last by Oliver North's ragtag air force.

The plane, however, attracted the attention of a teenage Sandinista soldier armed with a shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile. He aimed, pulled the trigger and watched as the Soviet-made missile made a direct hit on the aircraft. Inside, cargo handler Eugene Hasenfus, an American mercenary working with the Contras, was knocked to the floor, but managed to crawl to an open door, push himself through, and parachute to the ground, where he was captured by Sandinista forces. The pilot and other crew members died in the crash.

As word spread about the plane crash, Barger -- who had left the AP and was working for a CBS News show -- persuaded me to join him on a trip to Nicaragua with the goal of getting an interview with Hasenfus, who turned out to be an unemployed Wisconsin construction worker and onetime CIA cargo handler. Hasenfus told a press conference in Managua that the Contra supply operation was run by CIA officers working with the office of Vice President George Bush. Administration officials, including Bush, denied any involvement with the downed plane.

Our hopes for an interview with Hasenfus didn't work out, but Sandinista officials did let us examine the flight records and other documents they had recovered from the plane. As Barger talked with a senior Nicaraguan officer, I hastily copied down the entries from copilot Wallace "Buzz" Sawyer's flight logs. The logs listed hundreds of flights with the airports identified only by their four-letter international codes and the planes designated by tail numbers.

Upon returning to Washington, I began deciphering Wallace's travels and matching the tail numbers with their registered owners. Though Wallace's flights included trips to Africa and landings at U.S. military bases in the West, most of his entries were for flights in Central and South America.

Meanwhile, in Kerry's Senate office, witness Wanda Palacio was waiting for a meeting when she noticed Sawyer's photo flashing on a TV screen. Palacio began insisting that Sawyer was one of the pilots whom she had witnessed loading cocaine onto a Southern Air Transport plane in Barranquilla, Colombia, in early October 1985. Her identification of Sawyer struck some of Kerry's aides as a bit too convenient, causing them to have their own doubts about her credibility.

Though I was unaware of Palacio's claims at the time, I pressed ahead with the AP story on Sawyer's travels. In the last paragraph of the article, I noted that Sawyer's logs revealed that he had piloted a Southern Air Transport plane on three flights to Barranquilla on Oct. 2, 4, and 6, 1985. The story ran on Oct. 17, 1986.

Shortly after the article moved on the AP wires, I received a phone call from Rosenblith at Kerry's office. Sounding shocked, the Kerry investigator asked for more details about the last paragraph of the story, but he wouldn't say why he wanted to know. Only months later did I discover that the AP story on Sawyer's logs had provided unintentional corroboration for Palacio's Contra-drug allegations.

Palacio also passed a polygraph exam on her statements. But Weld and the Justice Department still refused to accept her testimony as credible. (Even a decade later, when I asked the then-Massachusetts governor about Palacio, Weld likened her credibility to "a wagon load of diseased blankets.")

In fall 1986, Weld's criminal division continued to withhold Contra-drug information requested by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. According to Justice Department records, Lugar and Pell -- two of the Senate's most gentlemanly members -- wrote on Oct. 14 that they had been waiting more than two months for information that the Justice Department had promised "in an expeditious manner."

"To date, no information has been received and the investigation of allegations by the committee, therefore, has not moved very far," Lugar and Pell wrote in a joint letter. "We're disappointed that the Department has not responded in a timely fashion and indeed has not provided any materials."

On Nov. 25, 1986, the Iran-Contra scandal was officially born when Attorney General Edwin Meese announced that profits from secret U.S. arms sales to Iran had been diverted to help fund the Nicaraguan Contras.

The Washington press corps scrambled to get a handle on the dramatic story of clandestine operations, but still resisted the allegations that the administration's zeal had spilled over into sanctioning or tolerating Contra-connected drug trafficking.

Though John Kerry's early warnings about White House-aided Contra gunrunning had proved out, his accusations about Contra drug smuggling would continue to be rejected by much of the press corps as going too far.

On Jan. 21, 1987, the conservative Washington Times attacked Kerry's Contra-drug investigation again; his alleged offense this time was obstructing justice because his probe was supposedly interfering with the Reagan administration's determination to get at the truth. "Kerry's staffers damaged FBI probe," the Times headline read.

"Congressional investigators for Sen. John Kerry severely damaged a federal drug investigation last summer by interfering with a witness while pursuing allegations of drug smuggling by the Nicaraguan resistance, federal law enforcement officials said," according to the Times article.

The mainstream press continued to publish stories that denigrated Kerry's investigation. On Feb. 24, 1987, a New York Times article by reporter Keith Schneider quoted "law enforcement officials" saying that the Contra allegations "have come from a small group of convicted drug traffickers in South Florida who never mentioned Contras or the White House until the Iran-Contra affair broke in November."

The drift of the article made Kerry out to be something of a dupe. His Contra-cocaine witnesses were depicted as simply convicts trying to get lighter prison sentences by embroidering false allegations onto the Iran-Contra scandal. But the information in the Times story was patently untrue. The AP Contra-cocaine story had run in December 1985, almost a year before the Iran-Contra story broke.

When New York Times reporters conducted their own interview with Palacio, she immediately sensed their hostility. In her Senate deposition, Palacio described her experience at the Times office in Miami. She said Schneider and a "Cuban man" rudely questioned her story and bullied her about specific evidence for each of her statements. The Cuban man "was talking to me kind of nasty," Palacio recalled. "I got up and left, and this man got all pissed off, Keith Schneider."

The parameters for a "responsible" Iran-Contra investigation were being set. On July 16, 1987, the New York Times published another story that seemed to discredit the Contra-drug charges. It reported that except for a few convicted drug smugglers from Miami, the Contra-cocaine "charges have not been verified by any other people and have been vigorously denied by several government agencies."

Four days later, the Times added that "investigators, including reporters from major news outlets, have tried without success to find proof of ... allegations that military supplies may have been paid for with profits from drug smuggling." (The Times was inaccurate again. The original AP story had cited a CIA report describing the Contras buying a helicopter with drug money.)

The joint Senate-House Iran-Contra committee averted its eyes from the Contra-cocaine allegations. The only time the issue was raised publicly was when a demonstrator interrupted one hearing by shouting, "Ask about the cocaine." Kerry was excluded from the investigation.

On July 27, 1987, behind the scenes, committee staff investigator Robert A. Bermingham echoed the New York Times. "Hundreds of persons" had been questioned, he said, and vast numbers of government files reviewed, but no "corroboration of media-exploited allegations of U.S. government-condoned drug trafficking by Contra leaders or Contra organizations" was found. The report, however, listed no names of any interview subjects nor any details about the files examined.

Bermingham's conclusions conflicted with closed-door Iran-Contra testimony from administration insiders. In a classified deposition to the congressional Iran-Contra committees, senior CIA officer Alan Fiers said, "with respect to [drug trafficking by] the Resistance Forces [the Contras] it is not a couple of people. It is a lot of people."

Despite official denials and press hostility, Kerry and his investigators pressed ahead. In 1987, with the arrival of a Democratic majority in the Senate, Kerry also became chairman of the Senate subcommittee on terrorism, narcotics and international operations. He used that position to pry loose the facts proving that the official denials were wrong and that Contra units were involved in the drug trade.

Kerry's report was issued two years later, on April 13, 1989. Its stunning conclusion: "On the basis of the evidence, it is clear that individuals who provided support for the Contras were involved in drug trafficking, the supply network of the Contras was used by drug trafficking organizations, and elements of the Contras themselves knowingly received financial and material assistance from drug traffickers. In each case, one or another agency of the U.S. government had information regarding the involvement either while it was occurring, or immediately thereafter."

The report discovered that drug traffickers gave the Contras "cash, weapons, planes, pilots, air supply services and other materials." Moreover, the U.S. State Department had paid some drug traffickers as part of a program to fly non-lethal assistance to the Contras. Some payments occurred "after the traffickers had been indicted by federal law enforcement agencies on drug charges, in others while traffickers were under active investigation by these same agencies."

Although Kerry's findings represented the first time a congressional report explicitly accused federal agencies of willful collaboration with drug traffickers, the major news organizations chose to bury the startling findings. Instead of front-page treatment, the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times all wrote brief accounts and stuck them deep inside their papers. The New York Times article, only 850 words long, landed on Page 8. The Post placed its story on A20. The Los Angeles Times found space on Page 11.

One of the best-read political reference books, the Almanac of American Politics, gave this account of Kerry's investigation in its 1992 edition: "In search of right-wing villains and complicit Americans, [Kerry] tried to link Nicaraguan Contras to the drug trade, without turning up much credible evidence."

Thus, Kerry's reward for his strenuous and successful efforts to get to the bottom of a difficult case of high-level government corruption was to be largely ignored by the mainstream press and even have his reputation besmirched.

But the Contra-cocaine story didn't entirely go away. In 1991, in the trial of former Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega for drug trafficking, federal prosecutors called as a witness Medellin cartel kingpin Carlos Lehder, who testified that the Medellin cartel had given $10 million to the Contras, a claim that one of Kerry's witnesses had made years earlier. "The Kerry hearings didn't get the attention they deserved at the time," a Washington Post editorial on Nov. 27, 1991 acknowledged. "The Noriega trial brings this sordid aspect of the Nicaraguan engagement to fresh public attention."

Kerry's vindication in the Contra drug case did not come until 1998, when inspectors general at the CIA and Justice Department reviewed their files in connection with allegations published by the San Jose Mercury News that the Contra-cocaine pipeline had contributed to the crack epidemic that ravaged inner-city neighborhoods in the 1980s. (Ironically, the major national newspapers only saw fit to put the Contra-cocaine story on their front pages in criticizing the Mercury News and its reporter Gary Webb for taking the allegations too far.)

On Oct. 4, 1996, the Washington Post published a front-page story, with two more pages inside, that was critical of the Mercury News. But while accusing the Mercury News of exaggerating, the Post noted that Contra-connected drug smugglers had brought tons of cocaine into the United States. "Even CIA personnel testified to Congress they knew that those covert operations involved drug traffickers," the Post reported.

A Post editorial on Oct. 9, 1996, reprised the newspaper's assessment that the Mercury News had overreached, but added that for "CIA-connected characters to have played even a trivial role in introducing Americans to crack would indicate an unconscionable breach by the CIA."

In the months that followed, the major newspapers -- including the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times -- joined the Post in criticizing the Mercury News while downplaying their own inattention to the crimes that Kerry had illuminated a decade earlier. The Los Angeles Times actually used Kerry's report to dismiss the Mercury News series as old news because the Contra cocaine trafficking "has been well documented for years."

While the major newspapers gloated when reporter Gary Webb was forced to resign from the Mercury News, the internal government investigations, which Webb's series had sparked, moved forward. The government's decade-long Contra cocaine cover-up began to crumble when CIA inspector general Frederick Hitz published the first of two volumes of his Contra cocaine investigation on Jan. 29, 1998, followed by a Justice Department report and Hitz's second volume in October 1998.

The CIA inspector general and Justice Department reports confirmed that the Reagan administration knew from almost the outset of the Contra war that cocaine traffickers permeated the CIA-backed army but the administration did next to nothing to expose or stop these criminals. The reports revealed example after example of leads not followed, witnesses disparaged and official law-enforcement investigations sabotaged. The evidence indicated that Contra-connected smugglers included the Medellin cartel, the Panamanian government of Manuel Noriega, the Honduran military, the Honduran-Mexican smuggling ring of Ramon Matta Ballesteros, and Miami-based anti-Castro Cubans.

Reviewing evidence that existed in the 1980s, CIA inspector general Hitz found that some Contra-connected drug traffickers worked directly for Reagan's National Security Council staff and the CIA. In 1987, Cuban-American Bay of Pigs veteran Moises Nunez told CIA investigators that "it was difficult to answer questions relating to his involvement in narcotics trafficking because of the specific tasks he had performed at the direction of the NSC."

CIA task force chief Fiers said the Nunez-NSC drug lead was not pursued then "because of the NSC connection and the possibility that this could be somehow connected to the Private Benefactor program [Oliver North's fundraising]. A decision was made not to pursue this matter."

Another Cuban-American who had attracted Kerry's interest was Felipe Vidal, who had a criminal record as a narcotics trafficker in the 1970s. But the CIA still hired him to serve as a logistics officer for the Contras and covered up for him when the agency learned that he was collaborating with known traffickers to raise money for the Contras, the Hitz report showed. Fiers had briefed Kerry about Vidal on Oct. 15, 1986, without mentioning Vidal's drug arrests and conviction in the 1970s.

Hitz found that a chief reason for the CIA's protective handling of Contra-drug evidence was Langley's "one overriding priority: to oust the Sandinista government ... [CIA officers] were determined that the various difficulties they encountered not be allowed to prevent effective implementation of the Contra program."

According to Hitz's report, one CIA field officer explained, "The focus was to get the job done, get the support and win the war."

This pattern of obstruction occurred while Vice President Bush was in charge of stanching the flow of drugs to the United States. Kerry made himself a pest by demanding answers to troubling questions.

"He wanted to get to the bottom of something so dark," former public defender Mattes told me. "Nobody could imagine it was so dark."

In the end, investigations by government inspectors general corroborated Kerry's 1989 findings and vindicated his effort. But the muted conclusion of the Contra-cocaine controversy 12 years after Kerry began his investigation explains why this chapter is an overlooked -- though important -- episode in Kerry's Senate career. It's a classic case of why, in Washington, there's little honor in being right too soon. Yet it's also a story about a senator who had the personal honor to do the right thing.

Shares