With a dead-even race that featured nearly endless possible Electoral College configurations, Election Day promised to bring a certain number of surprises. But perhaps none was as unexpected as the notion that President Bush, the most conservative and polarizing president of his generation, would come through the other side of the campaign as a moderate with a mandate. Yet in the days immediately following the historically close vote, that's how the political press corps often portrayed the president.

Newsweek seemed to be the most optimistic about the chances of a kinder, gentler second term, suggesting, "Bush could bring us together." The magazine's Web site posited, "With nothing left to prove, Bush's second-term presidency could be surprisingly centrist." Further, "there is every possibility that Bush's second term might prove to be different from his first, especially in foreign policy. And it won't be more radical."

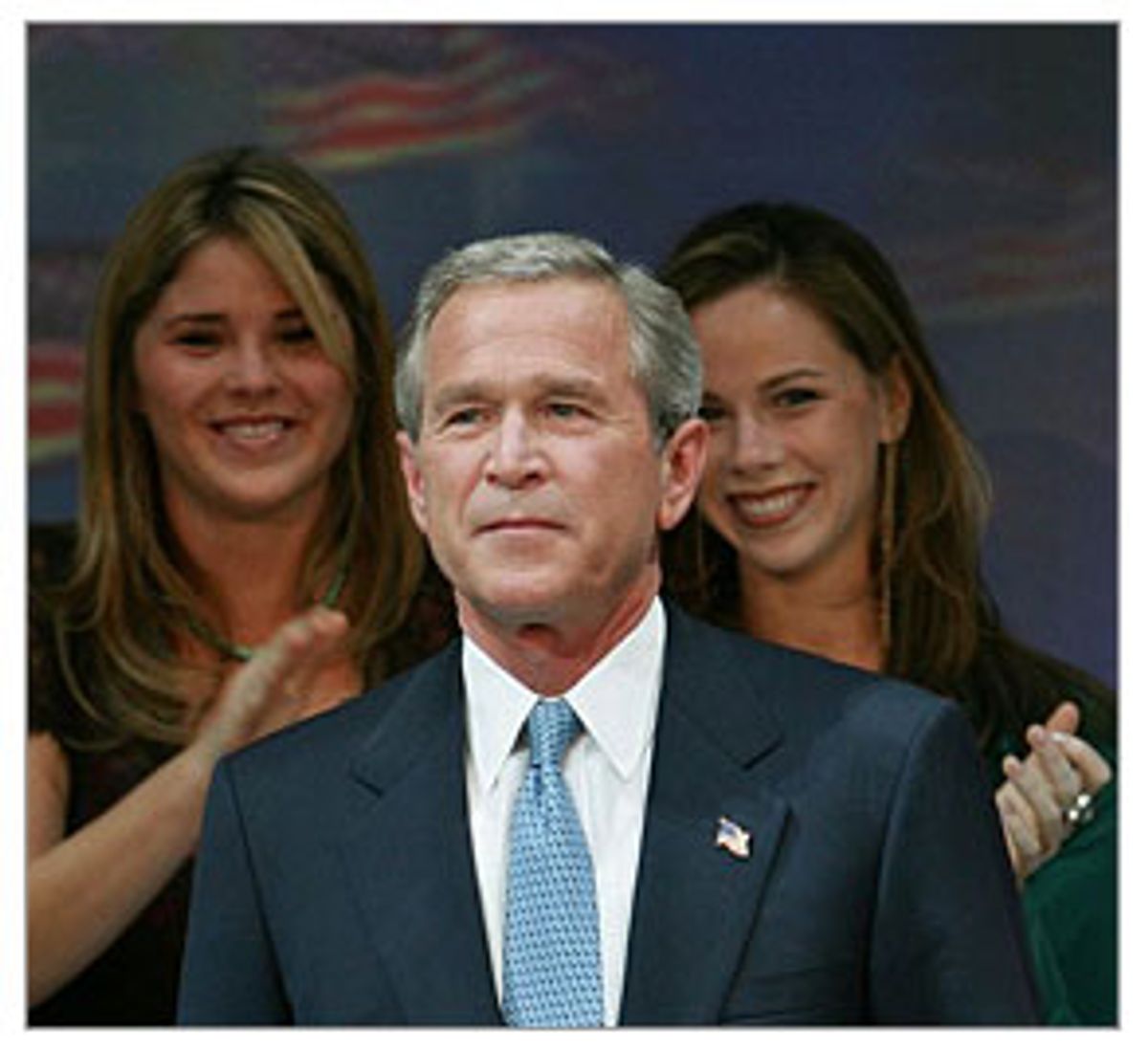

That's certainly the image the White House was projecting last week. "I pledge to do my part to try to bridge the partisan divide. Today, I hope that we can begin the healing," Bush said in his victory speech. Helping the administration's cause, the New York Times on Monday left unquestioned the assertion by a Bush aide that the president's chief domestic goal is to "solve the problems of poverty, the inner city and education," as well as persuade the country that "there really is such a thing as a compassionate conservative." Internationally, "Bush is determined to prove that it is not naive or impossible to try to foster democracy in the Middle East," the Times added.

When not busy describing Bush as a would-be centrist, White House aides were anxious to claim a sweeping mandate from the close election. And as liberal media watchdog group Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting documented, it worked. USA Today headlined a Nov. 4 story "Clear Mandate Will Boost Bush's Authority, Reach," which said that Bush "will begin his second term with a clearer and more commanding mandate than he held for the first." (The first being when he lost the popular vote to Al Gore.) The Boston Globe asserted that Bush's victory grants him "a clear mandate to advance a conservative agenda over the next four years," while MSNBC's Chris Matthews insisted, "To me the big story is the president's mandate. The president has a mandate."

But as Al Hunt noted in the Wall Street Journal, Bush's victory was "the narrowest win for a sitting president since Woodrow Wilson in 1916." (Presidential reelections in recent decades have all come with comfortable margins of victory attached.) In fact, Bush's final margin was almost identical to Jimmy Carter's win over Gerald Ford in 1976, when there was very little discussion of a mandate for the Democrat. And it's hard to imagine that if Kerry had bested Bush 51 percent to 48 percent and collected just 15 more electoral votes than needed to win, the press would be so liberal with talk of a mandate.

Some journalists, dwelling too much on 2000's unprecedented election model, seemed to confuse winning an uncontested election with receiving a mandate. "In capturing both an electoral majority and the popular vote, Mr. Bush lays claim to another four years in the White House with a newly minted mandate," the Dallas Morning News wrote, as if winning both the popular and Electoral College vote were somehow unusual in American politics.

In its Nov. 4 editorial, the Columbus Dispatch stated that "President Bush won reelection decisively in the Electoral College tally." Decisively? In the past 80 years, only three times have presidents been elected with fewer than 300 electoral votes. Bush accounts for two of the three anomalies; in 2000 he won 271 electoral votes, and in 2004 he captured 286. (Carter is the third example, with 297.)

The press's timidity toward the Bush White House is nothing new, and for the trend to continue after his victory is not that surprising. But it was hard not to be slightly taken aback while watching CNN's "Wolf Blitzer Reports" on Nov. 4, when it aired a segment about Bush's controversial call to privatize portions of Social Security savings. Only two experts were interviewed on camera -- one from the conservative American Enterprise Institute and one from the very conservative Heritage Foundation. Both enthusiastically supported Bush's unprecedented plan to move some retirement money into private investment funds.

And the press's now familiar deference toward Bush was on display in the New York Times over the weekend in a news story addressing a confirmed string of serious election mishaps in the crucial state of Ohio. "The way the vote was conducted there, election law specialists say, exposed a number of weak spots in the nation's election system," the Times reported. Yet before stating that fact, in its very first sentence, the Times article made the blunt assessment that "voters in Ohio delivered a second term to President Bush by a decisive margin" (emphasis added). Bush won Ohio by 2 percent. In fact, of the 30 states Bush carried last week, only two were won by slimmer margins than that in Ohio -- Iowa and New Mexico, which Bush won by 1 percent. Yet the Times, in an article documenting the shortcomings in Ohio's voting process, seemed to go out of its way to suggest, erroneously, that the too-close-to-call state voted for Bush by a "decisive margin."

Speaking of timid leads, on Monday the Times wrote: "Now that the election is over, there remains a piece of unfinished business: Whatever was that strange bulge in the back of President Bush's suit jacket that was visible during the three debates?"

The Times wasn't alone in its odd perspective during the campaign that some pressing stories were better told after voters had cast their ballots. In September, CBS's "60 Minutes" decided to delay until after the election an investigation into the Bush administration's use of forged documents on uranium from Niger in making its case for the Iraq war. A network spokesperson said at the time, "It would be inappropriate to air the report so close to the presidential election."

Meanwhile, press accounts subsequent to the election have been filled with reports about Bush's second term and his "very ambitious agenda," as the Associated Press described it. However, during the campaign very few journalists pressed Bush on his unusual decision as a sitting president not to articulate his vision for the future, beyond stump speech lines about lower taxes and less government. As NBC's David Gregory noted, after the election, "It's the agenda that Bush rarely if ever laid out in detail during the campaign."

For instance, Bush's sudden announcement last week that he planned to move aggressively to privatize Social Security may have caught some voters off guard. As Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson (professors at Yale and the University of California at Berkeley, respectively) noted in the New Republic, "On Social Security, administration officials have had four years to develop specific proposals. They have held back precisely because once an actual proposal is outlined it becomes clear what a dreadful deal it will be for most Americans." (Recent polls indicate a majority of Americans oppose the idea of privatizing Social Security.)

The administration obviously "held back" in blatant ways on other contentious initiatives, and met little or no questioning from the press. Few journalists addressed head-on the decision by Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist -- a political ally of Bush's -- to issue what now appears to be a deliberately misleading statement about his health, just one week before the election. More important, the all-out assault on Fallujah in Iraq, which some experts believe will include the heaviest fighting U.S. soldiers have faced since Vietnam, was finally launched, less than a week after the election. On the same day, the Iraqi government declared a 60-day state of emergency for most of the country. The two long-pending moves were likely put off until after the election for the simple reason that they could have potentially hurt Bush at the polls.

In fact, since Election Day some journalists have acknowledged that certain sensitive topics were deemed off-limits by the White House, or taken off the table for purely political reasons. "In Iraq, the American forces have been poised to make a major assault on Fallujah. We all anticipate that that could happen at any moment," said NBC's Tom Brokaw on Nov. 4. Addressing Pentagon correspondent Jim Miklaszewski, Brokaw asked, "What about other strategic and tactical changes in Iraq now that the election is over?" (emphasis added). Miklaszewski confirmed the obvious: "U.S. military officials have said for some time that they were putting off any kind of major offensive operation in [Fallujah] until after the U.S. elections, for obvious political reasons."

Appearing on CNN's "Reliable Sources" over the weekend, former CNN Washington bureau chief Frank Sesno, now a professor at George Mason University in Virginia, talked about Bush's second term: "How is the press corps going to react to the president? Are they going to see the wind at his back and feel all the pressure from conservatives and others, and become a sort of chorus press corps? [Or] are they going to become an attack dog press corps?"

Judging from the very early returns, the White House doesn't have to worry about any pit bulls in the press corps.

Shares