On the night her world changed forever, Rashida Bee was 28 years old and had already been married for more than half her life. Her parents, traditional Muslims, had selected her husband for her when she was 13. He worked as a tailor, and they lived together in her parents' modest home in the industrial city of Bhopal, in central India. Bee hadn't learned to read or write, and she ventured out of the house only when escorted by a male relative. It was nevertheless a full life; her extended family of siblings, nieces and nephews numbered 37 in all.

The fateful night came on a Sunday. Bee and her family had gone to bed after sharing a simple supper. But shortly after midnight, in the early hours of Dec. 3, 1984, Bee was awakened by the sound of violent coughing. It was coming from the children's room. "They said they felt like they were being choked," Bee later told the online environmental magazine Grist, "and we [adults] felt that way too. One of the children opened the door and a cloud came inside. We all started coughing violently, as if our lungs were on fire."

From out on the street came the sound of shouting. In the light of a street lamp, Bee saw crowds of shadowy figures running past the house. "Run," they yelled. "A warehouse of red chilies is on fire. Run!"

A few blocks away, a woman who would later become a dear friend of Bee's was also running for her life. Champa Devi Shukla, a 32-year-old Hindu, lived down the street from the pesticide factory owned by Union Carbide. She knew better than to believe the rumors about a warehouse fire. "We knew this smell because Union Carbide often used to release these gases from the factory late at night," Shukla later told me. "But this time it went on longer and stronger."

Shukla was right. An explosion inside the Union Carbide factory had sent 27 tons of methyl isocyanate gas wafting over the city's shantytowns. "The panic was so great," said Shukla, "that as people ran, mothers were leaving their children behind to escape the gas."

In the pandemonium, Bee too was separated from most of her family. She found herself running with her husband and father, but they didn't get far. "Our eyes were so swollen that we could not open them," she recalled. "After running half a kilometer we had to rest. We were too breathless to run, and my father had started vomiting blood, so we sat down."

The scene around them was apocalyptic. There were corpses everywhere, many of them children. Those people still alive were bent over double or splayed on the ground, retching uncontrollably or frothing at the mouth. Some had lost control of their bowels, and feces streamed down their legs.

Exactly how many people died that night will never be known; many corpses were disposed of in emergency mass burials or cremations without documentation. Bee remembers that as she searched for family members in the following days, "I had to look at thousands of dead bodies to find out if they were among the dead."

Perhaps the most extraordinary fact about Bhopal is that no one has faced trial for what happened that night. Even though Union Carbide's own safety experts had warned two years before of a "serious potential for sizable releases of toxic materials," the managers of the Bhopal factory had no system in place to warn and evacuate residents in the event of an emergency. Indian government officials likewise failed to insist upon such basic precautions. And as thousands of survivors streamed into local hospitals that night, Union Carbide spokesmen actively denied that methyl isocyanate was poisonous, calling it "nothing more than a potent tear gas."

Corporate officials have never answered in a court of law for their actions. Such an evasion of legal accountability would be inconceivable if the disaster had occurred in the United States or Europe. Had the victims been affluent Westerners rather than impoverished Indians, they would have had their day in court long ago.

India's courts have tried to pursue justice for Bhopal's citizens, but they have been thwarted. In 1991, an Indian court ordered Union Carbide officials, including Warren Anderson, the CEO at the time of the disaster, to face criminal charges. After Anderson and the other defendants failed to appear, India's Supreme Court named them "proclaimed absconders" -- that is, fugitives from justice -- and pressed for their extradition. After sitting on the extradition request for years, the U.S. State Department refused it without explanation in September 2004.

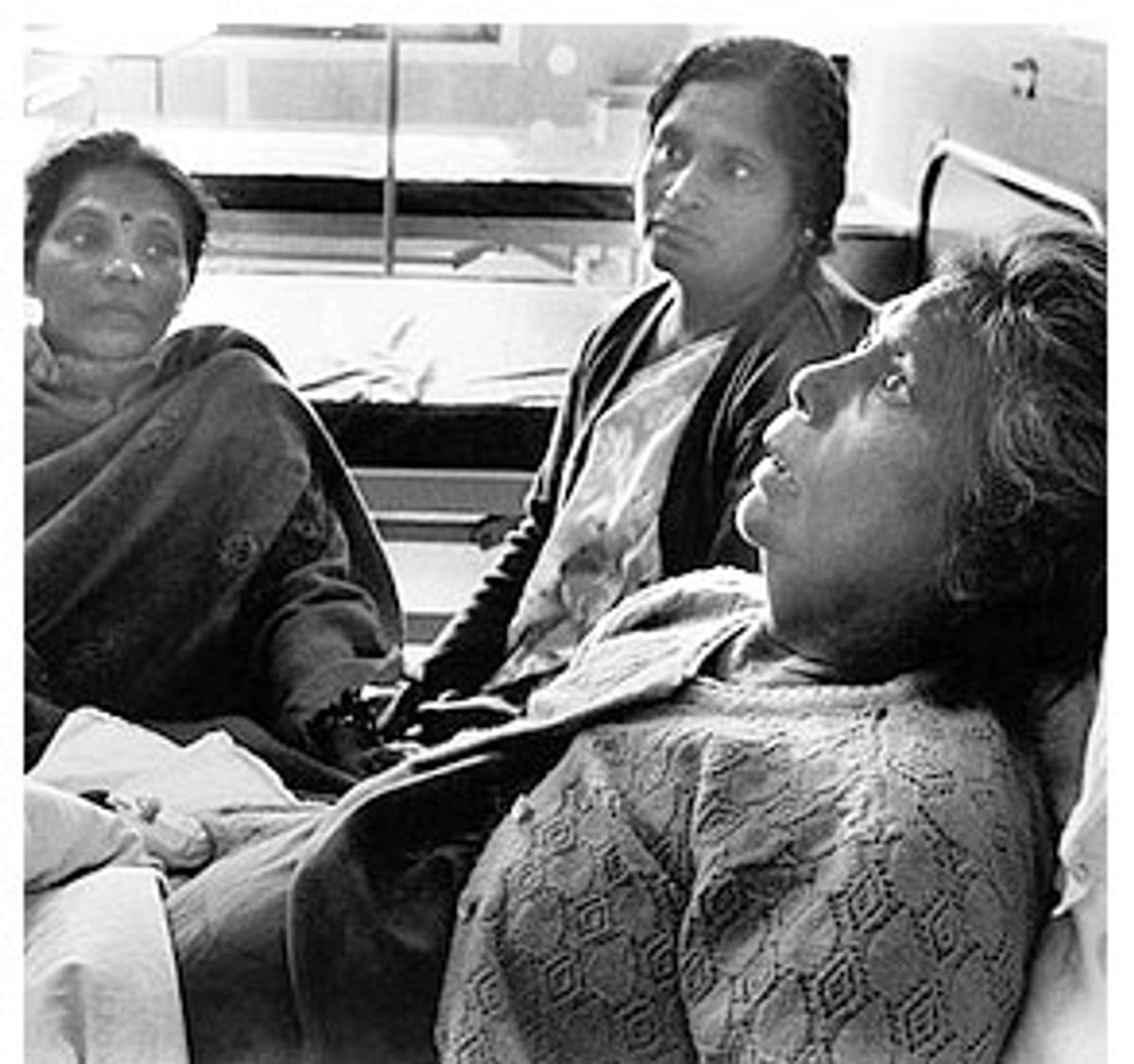

Bhopal survivors, however, have never stopped pressing their demands for a proper trial, appropriate compensation for victims, and sufficient medical, economic and environmental rehabilitation for survivors. And in this 20th anniversary of their struggle, they have gained new allies. In April, Bee and Shukla won the Goldman Prize, the biggest environmental award given in the United States. And this week, Amnesty International endorsed Bhopal activists' demands in a report launching Amnesty's first major campaign targeting a corporation for allegedly violating the human right to a healthy environment.

Amnesty's report, "Clouds of Injustice," estimates that 7,000 to 10,000 people died in the first three days of the Bhopal disaster, and that 15,000 more have died in the years since. An additional 100,000 continue to suffer chronic, largely untreatable diseases of the lungs, eyes and blood. Meanwhile, a new generation in Bhopal endures an epidemic of infertility and grotesque birth defects, including missing palates and fingers growing out of shoulders, in part because of continuing contamination of the groundwater.

Bhopal thus ranks as the single deadliest industrial disaster of the modern environmental era. With a death toll of approximately 22,000, it has killed more people than the nuclear disaster in Chernobyl, Ukraine, did. And its victims are still dying today, 20 years later.

Each Dec. 3, on the anniversary of the disaster, Bee and Shukla join other marchers who parade with an effigy of Anderson through the streets of Bhopal and then burn it. Bee and Shukla continue to hold Anderson, now 83 and retired, personally responsible for the Bhopal disaster, which they insist on labeling "a crime" rather than an "accident." "It was Anderson's criminal negligence and insistence on cost-cutting that led to the disaster," Shukla said.

Internal Union Carbide documents, released in the 1990s during the discovery phase of a civil lawsuit against the company, seem to support Shukla's contention. A 1973 document, signed by Anderson, notes that the technology that would be used in the Bhopal factory was "unproven." A safety review conducted by Union Carbide experts in 1982 warned of a "serious potential for sizable releases of toxic materials" at the factory.

John Musser, a company spokesman, confirmed the existence of the 1982 study but asserted, "None of the issues [it] raised would have had an impact on the fatal gas leak, and all of the issues had been addressed by the plant well before the December 1984 disaster." The real culprit, the company insists, was sabotage.

Anderson now appears to be living the life of a wealthy recluse, with luxury homes in Bridgehampton, N.Y., Manhattan and Vero Beach, Fla. Company officials declined to provide contact information for him for the purposes of this article. But when Bee and Shukla toured the United States last spring after winning the Goldman Prize, they considered trying to find Anderson and confront him face to face.

"We don't want him hanged or anything," Shukla said. "But he has to understand what it means to be cut off from one's family, what it is to suffer alone."

"If we see him," Bee added, "we will ask: If you are innocent, why are you hiding and not answering questions about what happened in Bhopal?"

Both Bee and Shukla lost loved ones in the disaster. Seven members of Bee's extended family died during or as a result of the disaster, and her husband was left too ill to continue his work as a tailor. Shukla lost her husband and two sons. A daughter later suffered three miscarriages, a grandson died, and a granddaughter was born with a cleft lip and a missing palate.

"The gas disaster was sudden, one night, but the last 20 years have also been miserable," Shukla said. "People still have pain and breathlessness, and now we are seeing cancers too. There is mental and physical retardation among children. Many women are sterile or never begin menstruating, so men don't want to marry them." A 2002 study commissioned by Greenpeace International but conducted by independent scientists concluded that Bhopal's groundwater contains heavy metals and levels of mercury millions of times higher than recommended. (Company spokesman Musser disputes those conclusions, citing studies in the late 1990s by government agencies in India.)

One bright spot has been the founding of the Sambhavna Trust Clinic to treat survivors of the disaster. Founded in the belief that compassion can create hope from despair, its name translates from Hindi as the Compassion Trust Clinic. Since opening its doors half a kilometer from the blast site in 1996, the clinic has treated thousands of Bhopal victims by combining the best of both Eastern and Western healthcare.

The staff biochemist, for example, doubles as a yoga teacher. Yoga is central to the clinic's approach, as is ayurvedic medicine. Patients pay nothing for treatment, even though they get far more care than at the crowded public hospitals that India's poor usually visit. First-time patients at Sambhavna have broken down in tears, the clinic's Web site reports, because "in 15 years no doctor had ever listened to their chests or taken their pulse during examination."

Yoga therapies have produced some of the most remarkable results. Chronic respiratory disorders are Bhopal gas victims' most prevalent complaint. A two-year study Sambhavna conducted indicates that regular yoga produces significant improvement in lung function; more than half of all yoga patients were able to stop taking pharmaceutical drugs treating breathlessness.

The clinic's staff includes community health workers who go door to door to monitor public health in Bhopal -- a key task since official monitoring stopped in 1994. These surveys aid doctors by showing which diseases are increasing. More broadly, the surveys prove that, 20 years later, locals continue to fall sick and die in large numbers.

Sambhavna's holistic approach sees both illness and healing in a social context. The clinic thus insists that the long-term solution to disasters like Bhopal is to eliminate hazardous chemicals from the environment altogether. Until then, "exemplary punishment" of corporate polluters is essential -- not only to achieving justice for Bhopal but to preventing future Bhopals elsewhere.

Along with activists from around the world, Bee and Shukla are seizing upon the 20th anniversary of the disaster this week to launch a renewed campaign for justice in Bhopal and, more broadly, to demand meaningful international regulation of toxic substances and the corporations that produce them. The Web site of the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal lists numerous planned actions and media events.

The most important development is the addition of Amnesty International to the campaign for justice in Bhopal. The human rights group's reputation for fearless evenhandedness lends weight to the conclusions in its "Clouds of Injustice" report. The report charges Union Carbide with "serious failures" at Bhopal, including ignoring "overwhelming evidence" of safety problems before the disaster, withholding information from doctors and investigators, and trying to avoid its legal and financial responsibilities for the disaster by shifting corporate ownership and dodging court dates.

The legal case against Union Carbide is complicated by the fact that Dow Chemical purchased all shares of Union Carbide in 2001 yet denies any legal responsibility for Carbide's past actions. "Dow remains firm in its position that in acquiring the shares of Union Carbide it acquired no new liability," says spokesman Musser.

This novel legal theory -- that one company can buy another company's assets but not its liabilities -- may soon be tested. Nitynand Jayaraman of the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal says that activists plan to press the Indian government to include Dow Chemical in the outstanding criminal case against Union Carbide; the government could then attach Dow's assets if it refused to appear in court. Gary Cohen, the director of the Environmental Health Fund in Washington, says, "Dow wants to expand in India, and we're going to make that very difficult" -- by raising questions about the trustworthiness of a corporation that refuses to heed a court summons.

Amnesty International has urged Dow Chemical, as Union Carbide's new corporate parent, to take a series of actions to make amends. Those actions include paying for a full cleanup of the Bhopal site and its contaminated groundwater, standing trial as requested in India, and paying full economic, medical and environmental reparations to the victims. More broadly, Amnesty echoes activists' call for tougher regulation of chemical production, especially in impoverished communities and countries. "Clouds of Injustice" proposes that the United Nations adopt an "international human rights framework that can be applied to companies directly" to ensure "transparency and public participation in ... the operation of industries using hazardous materials."

A further complication to this case is that Union Carbide did pay $470 million to the government of India in 1989 to settle all claims related to Bhopal. But there is much less to that settlement than meets the eye. The $470 million figure was based on now-discredited estimates that only 3,000 people died at Bhopal; the actual death toll is at least seven times that many. What's more, says Bee, "Carbide made that settlement with the government, not with the people affected. We don't accept it." And $330 million of the settlement money has been tied up in legal wrangling instead of reaching victims. When India's Supreme Court ordered in July that the $330 million be distributed forthwith, activists appealed the ruling, arguing that victims deserve four times that much.

Independent experts, including authors Arun Subramaniam and Ward Morehouse in their book "The Bhopal Tragedy," have estimated the total damages of the disaster -- including healthcare for survivors, compensation for families left without breadwinners, and restoration of local ecosystems -- total anywhere from $1.3 billion to $4 billion. Activists have filed a civil suit in the United States in an effort to force Dow Chemical to pay proper compensation.

Whatever the exact amount owed, it's clear that the people of Bhopal have been terribly mistreated. First they were left defenseless against a horrific but predictable disaster; then they were given a legal runaround for 20 years instead of just compensation for their suffering. There are many shades of gray in life, but sometimes the truth is black and white: It is shameful for Dow Chemical/Union Carbide to keep ducking its obligations in Bhopal and shameful for the U.S. State Department to help it do so. Doing the right thing -- standing trial and facing a court's judgment -- may cost the company financially, but continuing to stonewall could blacken its reputation forever.

Shares