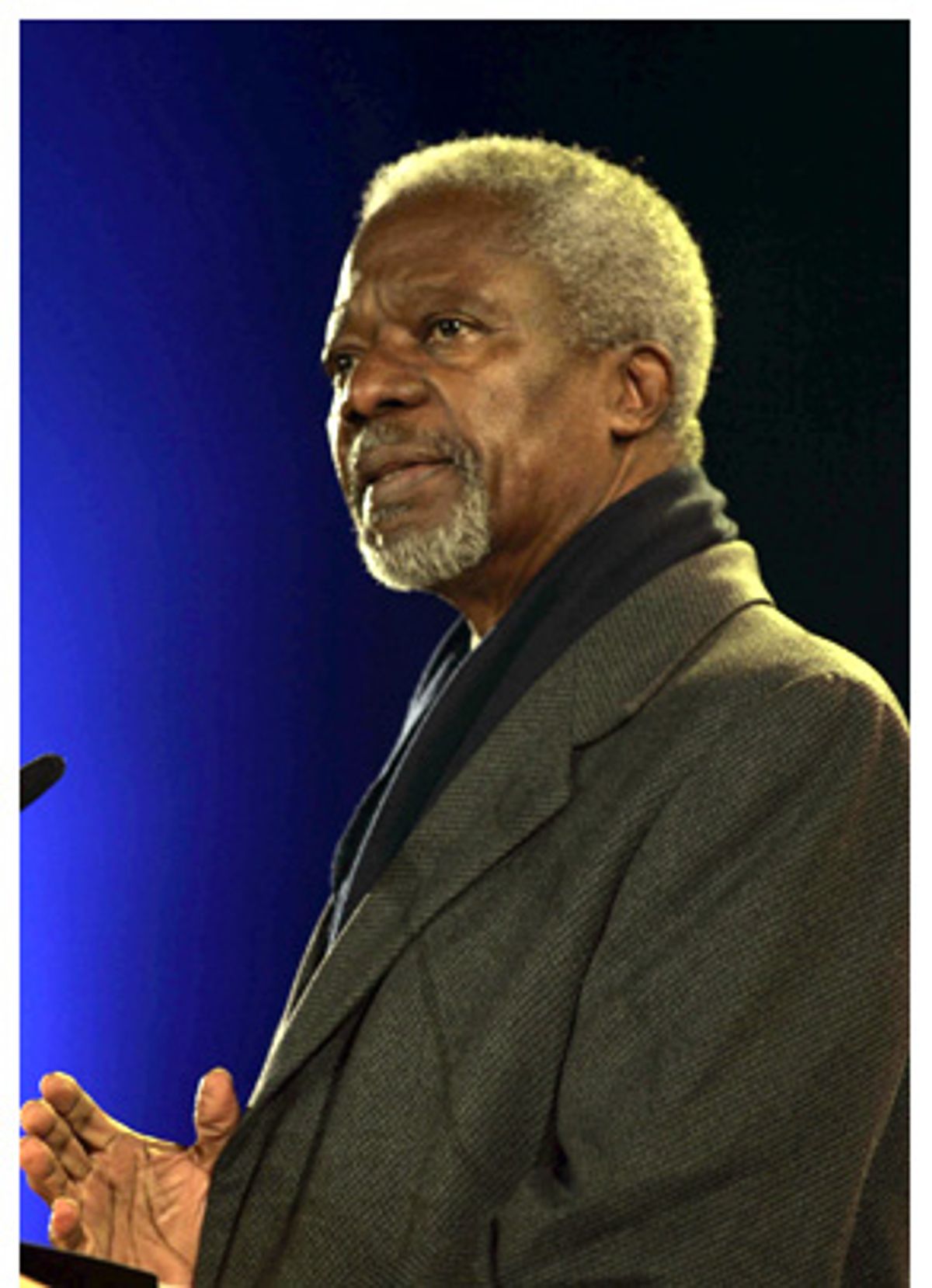

In an effort to increase the relevance of, and confidence in, the United Nations, which was created 60 years ago to prevent a repetition of World War II, Secretary-General Kofi Annan on March 21 presented several proposals for reform of the world body to reflect the changed nature of global conflicts since 1945. The title of his 63-page report is "In Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security and Human Rights for All."

It is emblematic that among the few actual changes he recommends to the text of the U.N. Charter are the deletion of its clauses penalizing Germany and Japan and the abolition of the Military Staff Joint Committee that was supposed to coordinate operations against any resurgence by those nations. The committee has met every two weeks for all those decades without making a single decision, and the "former enemy powers" are expected to be invited to join the former victors as permanent members of the U.N. Security Council.

Instead of rewriting the charter -- which would almost certainly lead to a weaker document than the briefly united Allies could achieve in 1945 -- what Annan proposes is in effect a reinterpretation of the charter to meet modern circumstances. Instead of being primarily about avoiding a repetition of World War II, he suggests that the United Nations should now focus on the new threats to peace.

In the biggest reinterpretation, he asks the Security Council, in place of the traditional sacrosanctity of national sovereignty, to deem mass murder, repression and ethnic cleansing to be threats to international peace and security that the international community has the right to intervene to stop -- and to adopt a set of principles to ensure that such intervention takes place only when there is no other option.

In another bold step, he proposes a succinct definition of terrorism and the creation of an international convention against it, along with strengthened controls on weapons to stop terrorists from getting their hands on them.

In case you think that's easy, remember that diplomats have been tying themselves in knots over a definition of terrorism since even before Sept. 11, 2001. The Bush administration's apparent working definition of terrorists as people whom we do not like who use violence leaves as much to be desired as definitions that justify any act as long as it is aimed against imperialism.

Annan's definition cuts across talk about liberation struggles and state terrorism and states, "Any action constitutes terrorism if it is intended to cause death or serious bodily harm to civilians or non-combatants with the purpose of intimidating a population or compelling a Government or an international organization to do or abstain from doing any act." Replying to critics who say this neglects misdeeds by governments, he notes that those are already covered by the Geneva Conventions and similar international laws against war crimes.

He also wants a more effective, and tyranny-free, Human Rights Council, to replace the current Human Rights Commission (whose members have included notorious violators of human rights), and new attention to building democracy and reconstructing failed states. While many developed countries have already called for such changes, Annan recognizes that a large majority of the world body still needs convincing, so he presents the package of reforms as a "deal" between the blocs of members. The developed world and the United States get what they've been asking for, in return for agreeing to put truth in the promises they made to the developing world five years ago about meeting specified goals to reduce poverty and underdevelopment with direct aid, loan forgiveness and an end to trade barriers, and to help combat AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.

As Annan says eloquently in his report, "We will not enjoy development without security, we will not enjoy security without development, and we will not enjoy either without respect for human rights."

The most visible change would be in the membership of the Security Council, a reform that will get far more attention than it merits, since most of the report is rightly concerned about what the existing members of the Security Council (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States and 10 temporary members) and the General Assembly do and how they do it. Annan proposes two alternatives, both of which would increase the size of the council by nine seats. Plan A calls for six new permanent members -- which would not have vetoes -- and three new members elected for two-year, nonrenewable terms. Plan B envisions eight new "semi-permanent" members elected for four-year, renewable terms and one new temporary member.

Many U.N. members would like to do away with the veto, but the world war that gave us a Catch-22 in fiction also gave us one in fact. The five existing veto holders can veto any attempt to remove their veto, and adding six new vetoes would not make the council any more efficient.

The dilemma U.N. experts confronted in adding new council members was that Japan pays almost as much in dues as the United States does, and Germany pays more than four existing permanent members do, but since existing veto holders can't be shifted, just adding new permanent members would leave the "South" even more underrepresented than it already is. There is a growing consensus on adding Japan, Germany, Brazil and India as permanent members, but the two proposed African seats are hotly contested, with Egypt, Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya angling for them.

Annan does not want the reform package to be held prisoner to the United Nations' traditional preference for "consensus." He suggests that these and other proposals be adopted by a two-thirds majority if necessary, since otherwise they might be held hostage by jealous states who were not nominated for permanent seats.

Adding to his case, Annan tactfully but accurately points out that the General Assembly, in which the developing countries have enough votes to call the shots, has failed in many respects to exercise its authority and has allowed itself to be marginalized, for example, by adopting resolutions that are watered down to ineffectuality in search of consensus.

With the arrival of unilateralist John Bolton at the United Nations, and possibly of interventionist Paul Wolfowitz at the World Bank, the time may not seem propitious for non-American interpretations of what the United States has said it wants, but Annan's proposals are like Goldilocks' porridge for most of the democratic world -- just right. Canada, Europe, Japan, Latin America, South Africa and others are likely to broadly agree with almost everything in the report. Those who may need persuasion are China and other persistent human rights offenders jealous of their sovereignty -- and some decision makers in Washington.

While some will see pandering to neo-imperial pretensions in Annan's proposals to have the Security Council explicitly accept principles for humanitarian intervention, the John Boltons of this world will see its obverse -- an attempt to set limits on U.S. action without Security Council approval, like the invasion of Iraq. Equally, one can doubt that the report's robust support for the Kyoto Protocol and other measures against climate change, for the International Criminal Court, and for the land-mine and small-arms conventions is exactly what Bolton and his colleagues in the Pentagon have in mind when they talk about U.N. reform. Nor will the call for developed countries to send 0.7 percent of their gross domestic product in aid to developing countries exactly be music to congressional ears: That would involve a fivefold increase in current levels of U.S. aid, which have already risen since their low point under President Clinton.

American observers looking at the mire-storm that has been directed at Annan in the U.S. media may wonder at his powers of persuasion. Indeed, much of the news coverage in the United States has implied that the reform package is in some way an attempt to evade current charges against him and the U.N., such as allegations of mismanagement of the oil-for-food program in Iraq and sexual misconduct by U.N. peacekeepers. In fact, these proposals were signaled five years ago at the U.N. Millennium Summit and have been developing ever since.

In most of the rest of the world Annan's prestige is undiminished -- and it is worth remembering that the White House did not join the conservative feeding frenzy on the oil-for-food allegations. It still needs the U.N.'s help in Iraq, and is trying to enlist it against Iran and Syria, Bolton's scorn notwithstanding.

In any case, Annan is not relying on his powers of persuasion alone. One of the purposes of the proposed deal is to get U.S. allies like Tony Blair to pressure the White House to go along with the package before the 60th anniversary summit at the U.N. headquarters in New York this September so that it can be ratified at that time. It would be silly to be too optimistic, but there are few such opportunities for a genuine change in how "we the peoples of the united nations" conduct our global affairs, and this package has a joint appeal to both altruism and self-interest -- which often prove more potent than either on its own.

Shares