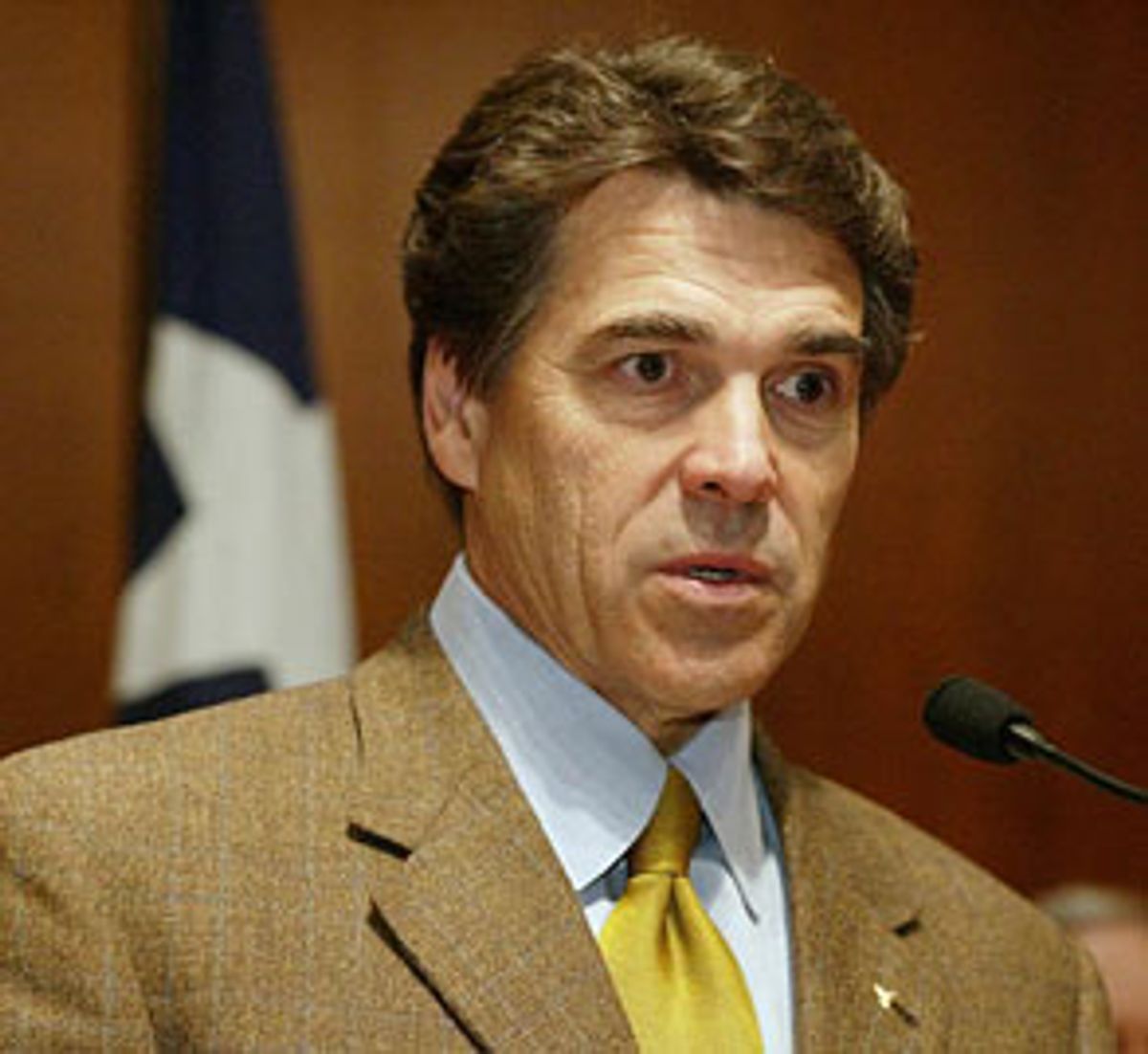

In January 2001, Texas Gov. Rick Perry concluded that it was time for the Texas Legislature to "take a good hard look" at allowing juries to sentence capital defendants to prison for the rest of their lives, with no chance for parole, instead of executing them. Three years later, Perry himself still had not made up his own mind on whether to give Texas juries the authority that jurors in 36 of the 38 death penalty states have. And that was too bad for Kelsey Patterson, a psychotic death-row inmate who believed his actions were controlled by implants in his brain. On May 18, 2004, Perry said he was compelled to deny Patterson clemency, despite an unprecedented 5-1 recommendation by the Texas parole board that the sentence be commuted to life in prison.

"After carefully reviewing all the facts in this case," the Republican governor said, Patterson would have to be executed because Texas had no statute mandating life without parole "and no one can guarantee this defendant would never be freed to commit other crimes were his sentence commuted."

In fact, Perry was fully aware that Patterson, a paranoid schizophrenic whom the state had once found to be legally insane, had about as much chance of being released from prison as he had of turning into a giant purple armadillo. But the governor was able to claim that Patterson might be freed because a murderer who is not sentenced to death in Texas receives a "life" sentence, which by definition means he must serve 40 years before becoming "eligible" for parole. Even though eligibility remains largely theoretical, it is a possibility, and on such nuances Kelsey Patterson was sent to the executioner.

Today, nearly a year later, Perry remains officially undecided about whether Texas should have a life-without-parole statute, and one can only assume he is still taking a good "hard look" at this not terribly abstruse issue.

Meanwhile, the Texas Legislature has been tinkering with the machinery of death, and it appears ready to approve a historic life-without-parole bill that could lead to a drastic reduction in Texas executions. And because Texas accounts for more than a third of the nation's executions, a change in Texas law would likely have a significant impact on the overall rate of executions nationwide.

Texas, as just about everyone knows, is the nation's execution capital. What most people don't understand is that many of these executions are the result of what is probably the most cynical and perverse sentencing statute in the country, a law that is deliberately misleading and designed to pressure jurors to vote for death rather than life sentences.

Because of the wording of Texas' capital sentencing law, a district attorney prosecuting a capital murder can use the same tortured argument in seeking a death sentence that Perry used in executing Patterson. He can tell jurors that unless they vote to kill the defendant, there is no "guarantee" that he will not be out on the streets murdering people again in their lifetime -- in a mere 40 years.

The prosecutors, like Perry, know that the likelihood of parole is close to nil, because the state's parole board, appointed by the governor, never grants parole to murderers. But they also know that when they tell a jury a killer could be released, jurors become alarmed and are much more inclined to vote for death as an "insurance policy" -- to insure that the killer can never go free and that they, the jurors, won't be responsible for another killing.

But why, one might ask, have Texas prosecutors fought to defend an ambiguous 40-year "life" sentence when they know it confuses juries, when the state could have a clear life-without-parole law? Why don't they trust juries to decide between a true life sentence and death?

The reason is that some prosecutors think jurors are wimps when it comes to imposing death. They like the current law because it tips the scales toward more death sentences and more executions. And why do prosecutors want more executions?

Well, they say death is warranted for the worst criminals and that it deters crime. Yet jurors would continue to have the option of imposing death even if a true life statute were passed. What prosecutors don't say is that more executions are good for their careers, that they embellish their tough-on-crime résumés and provide useful bragging rights when they run for reelection or higher office. For these prosecutors, current law provides the best of both worlds: confused juries are more likely to hand down death sentences, and the district attorney has the assurance that the defendant will never be released even if jurors reject death for a particular murderer.

But Paula Kurland says survivor families don't get to rest quite so easy. In 1986 Kurland's 21-year-old daughter, Mitzi Johnson Nalley, was stabbed to death in a vicious attack at her Austin apartment by a person who also took the life of her roommate, Kelly Joan Farquhar, 24, and who seriously injured a friend who tried to come to their aid. Kurland, a death penalty supporter who now works for victims of domestic violence and sexual assaults, says the murder of her daughter completely consumed her life until her daughter's killer was executed in 1998. "My children lost their sister and their mother the same night Jonathan Wayne Nobles brutally murdered my daughter and her roommate. Jonathan was the focus of my life for 12 years."

Kurland says that whether they support the death penalty or oppose it, what survivors want above all is "certainty" that the perpetrators of these crimes will never be free to kill someone else. The way to provide that certainty, she and an increasing number of Texas legislators as well as prosecutors say, is to give jurors in capital murder cases two choices: death or life without parole.

Kurland says that the current 40-year "life" law leaves survivors' families in a state of limbo because parole remains a possibility, however remote. "And if I'm not alive to fight to keep my child's killer in prison, then I have to pass that burden on to my children or grandchildren. And that's a horrible burden to pass on to anyone."

To remedy that situation and bring Texas into the 21st century -- and more in line with the death-sentencing practices of other states -- state Sen. Eddie Lucio Jr., a Democrat and death penalty supporter, authored the pending legislation to allow juries to impose an unambiguous life sentence when they determine that there are mitigating circumstances that warrant sparing the defendant from death. "Life without parole means certain punishment," Lucio says. Or it would, if the one he proposes replaces the current law.

In addition to the 36 death penalty states that currently provide the option of life without parole, juries in 11 of the 12 non-death-penalty states have that option.

Lucio had originally proposed retaining life with parole as a third option for jurors. That would leave open the possibility that the parole board might show mercy for a convicted murderer dying of an incurable illness. Or the board might conclude that someone who killed at 18 had changed his life and was no longer a menace to society by age 58 or 88. But Lucio was forced to drop the third option to win passage of his bill in the state Senate.

Somehow, what was once the tough-on-crime position -- saving the current law with parole eligibility -- has become a weak-kneed position compared to the life-versus-death approach.

This is not entirely surprising inasmuch as legislators have come to recognize that current law has a huge element of flimflam. This is a law, after all, defended by prosecutors who argue that the possibility of parole gives prisoners "hope" and makes them less prone to violence once incarcerated. Then again, these prosecutors also argue for death sentences because, they say, you can't be sure the defendants won't kill fellow prisoners and prison guards.

Lucio has been using a soft sell to win passage of his bill, suggesting that it won't really change very much and that it's primarily designed for the benefit of crime victims. But Steve Hall, director of the Standdown Texas Project, which advocates on behalf of reforms in the Texas capital-punishment system, believes the changes "would have the potential to significantly reduce the number of death sentences." Richard Dieter of the Death Penalty Information Center, an anti-death-penalty research group in Washington, thinks executions in Texas could decline by as much as 25 percent.

Opponents of Lucio's life-without-parole bill suggest that it could literally doom the death penalty in Texas, a claim many find far-fetched in a state where 75 percent of the population consistently supports capital punishment. At a recent hearing on the bill, Dallas County assistant district attorney John Rolater argued that abolitionists hope to use life without parole as a "step in eliminating what we view as an important penalty."

Although there is no direct evidence in other states correlating life-without-parole statutes with reduced death sentences, there are a number of reasons to believe that Texas death sentences will decline if this law is enacted.

First, the number of death sentences nationwide has been declining as more and more states have introduced life without parole. Second, although all jurors in a capital murder trial must favor the death penalty, some jurors are clearly going to be less gung-ho about the idea of executing someone than the average Texas prosecutor. Jurors' decisions are likely to be less cluttered by any need to prove how tough they can be on violent criminals. And unlike prosecutors who come into these cases prepared to argue that the defendant deserves death, jurors are supposed to listen to both sides of the argument. Third, when jurors are confronted with a real live human being, some may be queasy about taking another life and may be open to mitigating factors that prosecutors generally pooh-pooh, including evidence that the defendant had a horrible childhood, was sexually abused or beaten, is mentally ill, or was high on drugs at the time of the crime. Finally, jurors may opt for life over death when they have lingering, undefined doubts about a defendant's culpability.

In short, jurors are unpredictable, and even though they may support the death penalty, are likely to be more open to life without parole if they're given a clear understanding that there is no chance a defendant will be released.

Lucio's bill has already been approved by the Texas Senate and by a House committee and is now awaiting action in the full House. Approval there is considered likely.

Why the Legislature seems more willing to contemplate "truth in sentencing" this year when it has been intransigent on the subject in past sessions owes to a confluence of factors. Perhaps most important is that Texans, like other Americans, have begun to recognize how seriously flawed their criminal justice system really is. Although Perry and his predecessor, George W. Bush, seemed to view the system as some sort of immaculate conception, Texas newspapers have been filled with reports over the past two years about an ongoing scandal in the Houston police department's crime lab, where multiple errors have been discovered in the testing of DNA, ballistic, serology and toxicology evidence. At the same time, a growing number of U.S. Supreme Court opinions have rebuked the Texas courts for tolerating police and prosecutorial excesses -- including the withholding of evidence and the racial profiling of jurors -- and a law that violated the rights of defendants with mental retardation. Meanwhile, 15 innocent people were released from the state's prisons based on DNA evidence, and eight men were released from the state's death row due to evidence of innocence. Texans may be unusually tough on crime, but most of them presumably don't believe in punishing or executing innocent people.

An additional reason for progress on life without parole this year is that a significant rift has opened between prosecutors from the state's largest counties -- accounting for 75 percent of the state's murder trials -- who continue to oppose any change in the law, and prosecutors in small towns and rural counties. The latter are no less enthusiastic about the death penalty, but they've come to recognize that prosecuting a time-consuming death penalty case can bankrupt their treasuries. For these prosecutors it makes more sense to empower jurors with an honest, clear-headed understanding of their options and allow them to be the final arbiters of a murderer's fate.

Meanwhile, Perry, a die-hard death penalty supporter who is expected to face a tough reelection challenge from U.S. Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, sits on the fence in the life-without-parole debate. But with 78 percent of Texans saying they favor a true life-without-parole law, it seems highly likely the governor will go along with the popular will if the bill clears the Legislature before the current session ends later this month.

Shares