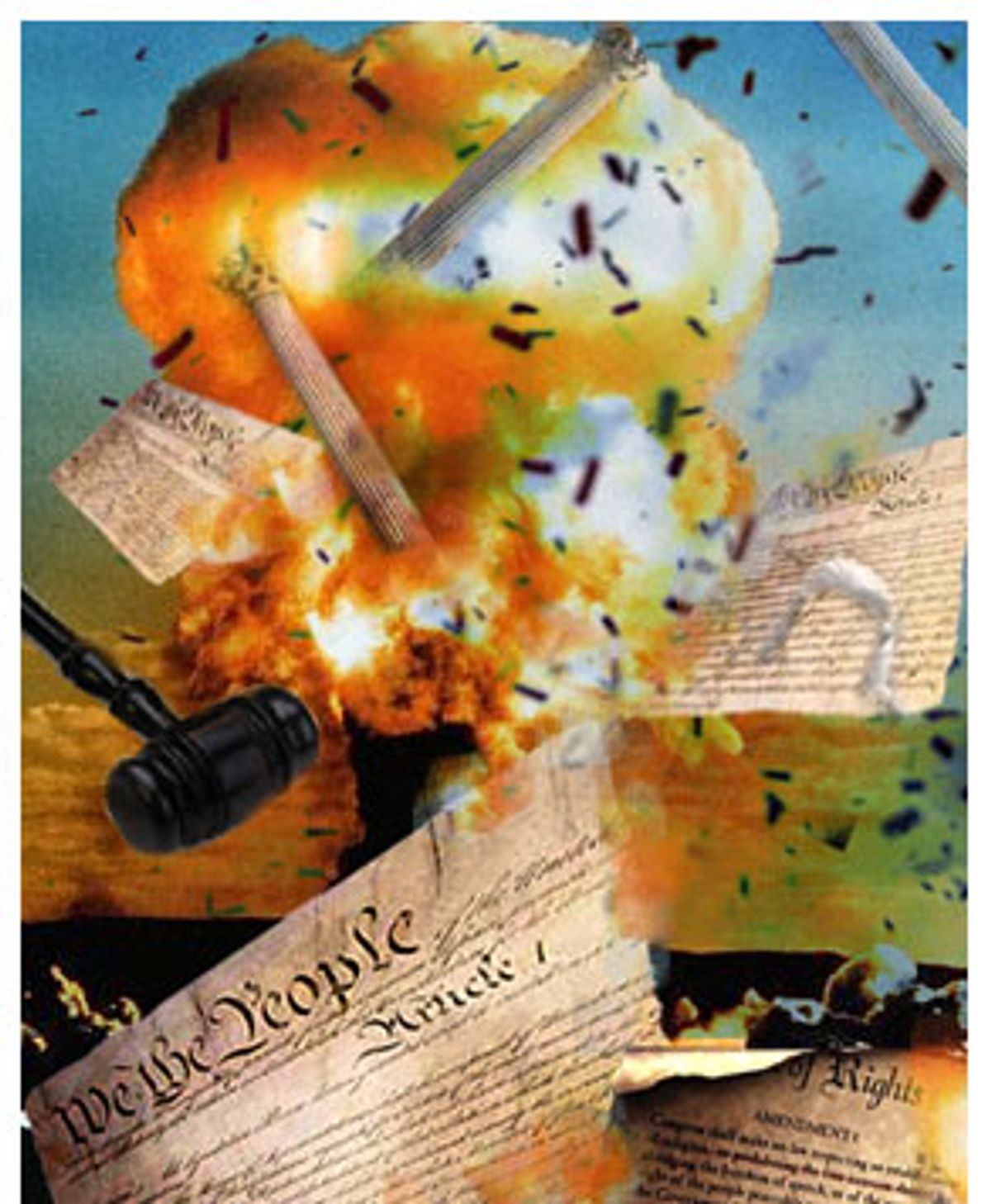

To hear the partisans on either side describe it, the coming debate over Bill Frist's plan to kill the filibuster is a thing of apocalyptic proportions. Focus on the Family's James Dobson says the ground in Washington is "almost too hot to walk on" right now, that the faithful are in their "foxholes" and the "bullets are flying overhead." Democratic National Committee chairman Howard Dean says Republicans are fixing to "blow up 200 years of Senate history" just because they're not getting their way on a handful of "radical" judicial nominees. On Capitol Hill, the threat of the "nuclear option" has created a sort of political ground zero, and activists on both sides believe that the way this thing plays out will control the shape of the federal judiciary -- and with it, the interpretation of the U.S. Constitution -- for decades to come.

Out there in America, it's a different story. The latest Gallup Poll reveals that only 35 percent of the country admits to following the filibuster fight closely -- more than will fess up to watching the Michael Jackson trial closely, but a little fewer than the percentage who claimed to be paying attention to the situation in Kosovo in 1999.

So if you haven't been giving your undivided attention to Priscilla Owen, Abe Fortas -- he's dead, but he plays into this -- and the intricacies of Senate Rule XXII, you can feel proud that you're right in the middle of the American mainstream. But now it's time to pay attention. A vote on Frist's "nuclear option" may come as early as next week, and we're here to help you get up to speed.

Call it a primer on the judicial confirmation process. Call it what you get when you spend way too much time reading Riddick's Senate Procedure. Just don't call it the "nuclear option" -- at least not when Bill Frist is around to correct you. The Senate majority leader doesn't want his plan to sound so explosive, but be forewarned: Unless somebody blinks first, we're in for a mind-warping set of unprecedented Senate maneuvers that could put Dick Cheney in charge of deeming the filibuster "unconstitutional" -- without a word from those folks in black robes across the street -- and grease the way for each and every right-wing extremist George W. Bush ever cares to put on a district court, an appellate court or the U.S. Supreme Court.

OK, let's begin at the beginning. What's the "nuclear option"?

It's Frist's plan to change the Standing Rules of the Senate in order to prohibit Democrats from using the filibuster to block votes on Bush's judicial nominees. Under the current rules, senators in the minority can indefinitely delay a floor vote on judges -- or on just about anything else, for that matter -- by engaging in extended debate.

The Senate's rules have allowed unlimited debate, or filibusters, since 1806, when senators dropped a rule that allowed a majority of the Senate to put an end to discussion and call for a vote. For the next 111 years, there was no way to stop a filibuster once it had started. But in 1917, when filibusters were blocking Woodrow Wilson's plans for World War I, the Senate adopted Rule XXII, which allowed senators to end a filibuster by a two-thirds vote on a motion to cut off debate -- a procedure called "cloture." In 1975, the Senate amended Rule XXII so that cloture required, in most cases, the vote of not two-thirds but rather three-fifths of the senators. In today's 50-state, 100-member Senate, that means it takes 60 rather than 67 senators to put an end to most filibusters.

With the nuclear option, Frist and his supporters would effectively change that rule so that filibusters on judicial nominees could be cut off by a simple majority vote.

Why is it called the "nuclear option"?

The Republicans don't call it the "nuclear option" -- well, at least they try not to call it that anymore. Trent Lott, who is a Republican if there ever was one, was the first to apply the term to the GOP plan, a recognition that killing the filibuster would be an explosive move in the Senate -- a body that has always prided itself as a place that cools the passions of the House of Representatives and keeps an eye out for the rights of the minority. The name stuck, and Republicans used it frequently.

But at some point along the line, the usually masterful GOP message mavens figured out that a "nuclear" option didn't sound very appealing. So Frist began correcting reporters who used the term, urging them to use the more palatable "constitutional option" instead.

The tactic has worked. As Media Matters has noted, reporters now frequently say that the "nuclear option" is what "Democrats call" the attempt to kill off the filibuster. And NBC's Chip Reid got himself so spun around the other day that he said that the "nuclear option" refers to the steps Democrats might take to retaliate if Republicans kill the filibuster. Frist spins things a different way still: He says the "nuclear option" is what the Democrats "did to me last year when they changed the precedent" on the handling of judicial nominees.

What did the Democrats do to Bill Frist?

Frist is upset that Democrats have used the filibuster to block a handful of Bush's judicial nominees. Democrats have allowed 205 of Bush's judicial nominees to be confirmed, but they have used the filibuster -- or, more accurately, the threat of the filibuster -- to prevent floor votes on 10 others. Bush offered all 10 of the nominees who were stalled in the last session of Congress the chance to be nominated again. Seven accepted, Bush renominated them, and Democrats have indicated that, except as some kind of compromise on the nuclear option, they'll block them again this session.

Democrats have allowed 205 to be confirmed and now are blocking only seven? That's not so bad, is it?

No, it isn't. According to an analysis by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service, Bill Clinton nominated 443 judges to U.S. district and appellate courts, and only 372 of those nominees were confirmed. George H.W. Bush got only 192 of his 242 nominees confirmed. Ronald Reagan went 375 for 403.

President Bush's numbers look pretty good by comparison. But the Republicans say those are the wrong numbers to consider, that one should consider the confirmation rate only for the judges that Bush has nominated to the U.S. Court of Appeals, the level of the federal judiciary one step above the district courts and one step below the Supreme Court.

So let's look at those numbers. Bush has nominated 52 judges to appellate courts, and the Senate has confirmed 35 of them. (Democrats used the filibuster or the threat of filibuster to block 10, and seven other nominations were returned to the White House for other reasons.) How does that compare with, say, Clinton's record? It's almost identical. In his second term, Clinton nominated 51 appellate court judges. The Republican-controlled Senate confirmed 35 of them. Overall, the Congressional Research Service says that Clinton went 65 for 91 on nominees to appellate courts -- a .714 batting average that's not a whole lot different from Bush's .673. And Bush would actually out-hit Clinton if Frist and other Republicans accepted a nuclear option-averting compromise plan now under discussion on Capitol Hill.

But there must be something different in the way that the Democrats are blocking Bush's nominees, right? The Republicans say that what the Democrats are doing is "unprecedented."

Oh, yes they do. Just the other day on Fox News, Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, the former chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, proclaimed: "We've never had a filibuster of judges in the history of this country." In a myth vs. fact sheet, the Republican National Committee says that "having to overcome a filibuster (or obtaining 60 votes) on judicial nominees is unprecedented."

But that's not a fact. In 1968, Republicans led a filibuster against Lyndon Johnson's nomination of Abe Fortas as chief justice. And that isn't the only Republican attempt to filibuster a judicial nominee in recent history. During the Clinton years, the Congressional Research Service says, Democrats were forced to bring cloture motions on six judicial nominees. While the existence of a cloture motion doesn't always mean that a filibuster is in effect, in at least some instances it has meant just that: In 2000, Frist himself voted to support a filibuster against Richard Paez, Clinton's nominee to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

What do Frist and the GOP say about that?

They've become more and more specific about what it is they're calling "unprecedented." Now, instead of saying that filibusters are unprecedented, Frist says that a judicial nominee "with majority support" has "never been denied" an up-or-down vote. That formulation is closer to accurate, but it's still not quite there. Paez had "majority support," but Frist and other Republicans tried to filibuster his confirmation anyway.

What gives? Frist would say that the Republicans didn't succeed in blocking the Paez nomination, so their efforts shouldn't count against them. It's a sin to succeed in blocking a nomination by filibuster, Republicans say. But trying to block a nomination by filibuster -- as Republicans did repeatedly during the Clinton years? That doesn't count, and to say otherwise would be, in the words of the conservative Committee for Justice, "Orwellian."

Isn't that a little like an attempted murderer lording his morality over a murderer who actually succeeds?

You said it, not me.

Do all Senate Republicans go in for this way of thinking?

Not all of them. Arizona Sen. John McCain and Rhode Island Sen. Lincoln Chafee have already said that they'll vote against the nuclear option, and there are at least six other Republicans who could go either way. Over the weekend, Nebraska Sen. Chuck Hagel seemed to be saying he wouldn't go nuclear, explaining that Republicans' "hands aren't clean" on judicial nominees, either.

Does that mean Republicans didn't always provide up-or-down votes on Clinton's judicial nominees?

That's right, they didn't. As Hagel noted, Republicans prevented approximately 60 of Clinton's judicial nominees from ever getting a hearing from the Senate Judiciary Committee. They didn't have to use filibusters to block floor votes on the nominees because they never let them get that far in the first place.

Why can't Democrats do the same thing to Bush's nominees?

In large part because Hatch changed the rules of the Judiciary Committee. When Clinton was president and Hatch controlled the committee, a judicial nomination could be put on permanent hold if a single senator from the nominee's home state objected to its going forward. But in 2003, Hatch changed the rules to make it harder for a single Democrat to block a Bush nominee. Under Hatch's new formulation, "blue slips" couldn't stop a nomination unless both senators from the nominee's home state submitted one -- and he wavered on whether he should consider himself bound by the "blue slips" at all.

Now Arlen Specter is the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, and he has started to move some of the stalled nominees through the committee so that they'll be teed up for floor votes -- or at least for filibusters over floor votes. And unless somebody blinks before then, that means the nuclear option could come to a head as early as next week.

But aren't there rules about changing the rules in the middle of the game?

Yes, there are. Senators may amend the Standing Rules of the Senate by a simple majority vote. But -- and you saw this coming, didn't you? -- proposals to change the Senate's rules are subject to filibuster, too. So if Republicans simply followed the rules about changing the rules, and if Democrats filibustered the rule change, as they surely would, then Republicans would need to cobble together enough votes to prevail on a cloture motion.

That's 60, right?

Well, no. While it takes three-fifths of the Senate, or 60 votes, to cut off debate on most things, the Senate has previously recognized that changing the rules of the game should require something more. Thus, Senate Rule XXII says that debate on a "a measure or motion to amend the Senate rules" can't be cut off without an "affirmative vote" from "two-thirds of the Senators present and voting." That means that Frist would need 67 votes to cut off debate on a change in the Senate's rules. With only 55 Republicans in the Senate, and at least two of them unequivocally opposed to the nuclear option, Frist can't possibly get 60 votes to change the Senate's rules, let alone the 67 that Rule XXII requires.

Is that the end of it, then?

Well, it would be if Frist and the Republicans who are with him on this were inclined to follow the Standing Rules of the Senate. But they're not.

So how will Frist go nuclear?

It's hard to say for sure. As the Congressional Research Service says, "Exactly because the point of a 'nuclear' or 'constitutional' option is to achieve changes in Senate procedure by using means that lie outside the Senate's normal rules of procedure, it would be impossible to list all the different permutations such maneuvers could encompass." But here's how the Congressional Research Service and interest groups on both sides say that it could work.

First, Frist brings one of the stalled judicial nominees to the Senate floor for an up-or-down vote. The Democrats filibuster. The Republicans try to cut off debate through a cloture motion brought under Rule XXII, which requires the support of 60 senators. The cloture motion fails. At that point, the Congressional Research Service says, one of at least two things could happen.

In the first variation, the man presiding over the Senate at that moment, probably Vice President Dick Cheney or Senate President Pro Tempore Ted Stevens, could declare Rule XXII unconstitutional and rule that, when it comes to judicial nominations, debate can be cut off by a simple majority vote. Democrats could appeal that ruling, which would then set off another round of filibustering. But a Republican senator could move to table the appeal -- a move that's not subject to filibuster -- and then Republicans could vote by a simple majority to do so. That would effectively dismiss the appeal, allowing the ruling from the presiding officer to stand. Rule XXII would be declared unconstitutional, and the majority could end debate on any judicial nominee with a simple majority vote.

In the second variation -- and this part is required reading only for the Robert's Rules of Order fetishists among us -- a Republican senator, fresh off the loss on the initial cloture motion, could raise a point of order arguing that the requirement of a three-fifths vote to cut off debate on judicial nominees is unconstitutional. The presiding officer could submit that question to the full Senate for a vote. Under the Standing Rules, that vote would be subject to a filibuster, too. But the presiding officer could simply declare that it wasn't. That would lead, as in the first variation, to another appeal, another tabling motion, and then another simple majority vote on the question whether Rule XXII is unconstitutional.

In either variation, the end result is that Frist -- with 50 Republican votes and a tiebreaker from Cheney -- could get the Senate to declare that the usual cloture rule is unconstitutional when it comes to judicial nominees. All nominees could henceforth be confirmed with simple majority votes -- i.e., with the support of Cheney and just 50 of the Senate's 55 Republicans.

Wait a minute. Cheney gets to declare unconstitutional -- a power usually left to the courts -- a rule of the Senate, the authority for which is vested in the Senate, to get the president's judicial nominees through Congress? What about the separation of powers?

You catch on quick. As McCain has said, "It's not called 'nuclear' for nothing."

But can they really do that? Can Frist and the Republicans who support him just change the rules of the Senate in the middle of the game?

Yes and no. Yes, they can; and no, they can't without breaking Senate precedent. As the Congressional Research Service explains, each of the variations set forth above "would require that one or more of the Senate's precedents be overturned or interpreted otherwise than in the past."

In the first variation, the presiding officer -- Cheney or Stevens -- would take it upon himself to declare Rule XXII unconstitutional. Riddick's, considered the bible of Senate procedure, has this to say about that: "Under the precedents of the Senate, the presiding officer has no authority to pass upon a constitutional question, but must submit it to the Senate for its decision." By unilaterally deeming Rule XXII unconstitutional, Cheney or Stevens would be violating that precedent.

If the presiding officer chose the second variation instead -- that is, if he submitted the question of the constitutionality of Rule XXII to the full Senate for a vote -- the Congressional Research Service says he'd still have to break with Senate precedent by declaring that the question isn't subject to debate and therefore isn't subject to a filibuster by the Democrats.

But forget the procedural stuff for a minute. Is Rule XXII -- or what the Democrats are doing with it -- really unconstitutional?

That's a hard case to make -- and one that no federal court is likely to touch. Frist argues that the Framers "concluded that the president should have the power" to appoint judges "and the Senate should confirm or reject appointments by a simple majority vote." But the Constitution doesn't say that exactly. Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 says only that the president shall nominate judges "by and with the advice and consent of the Senate."

The right argues that the "simple majority" requirement should be read into that provision of the Constitution by reverse implication: The Constitution explicitly requires super-majority votes in only a few situations, including the ratification of treaties, the overriding of vetoes, the approval of constitutional amendments and the expulsion of a member of Congress; because the Constitution doesn't say anything about a two-thirds majority when it comes to judges, the right argues, it must require that judges be confirmed by a simple majority vote.

Democrats, on the other hand, cite Article I, Section 5, Clause 2 of the Constitution, which grants each house of Congress the right to "determine the rules of its proceedings." Under that provision, the Senate could make decisions on judges by rochambeau if 50 senators voted to make that the rule and 67 senators were around to kill off the filibuster that would follow.

In the end, however, the question of the filibuster's constitutionality is pretty academic. A federal court is unlikely to rule on the legality of the Senate's procedural rules, both because courts generally refrain from making such decisions under what's called the "political question doctrine" and because the Constitution expressly leaves the right to "determine the rules" of Congress to Congress -- which is to say, not to the federal courts.

But even if it's not unconstitutional, isn't the filibuster a little undemocratic?

Fair point. If democracy is all about the will of the majority, then the filibuster is undemocratic because it thwarts the majority's will. But the Senate isn't the most democratic of institutions, and it wasn't meant to be. Senators are like eyeballs; everybody gets two, no matter how big or small you are. New York gets two senators, but so does Wyoming. Thus, as E.J. Dionne Jr. has noted, the 52 senators from the 26 least populous states "could command a Senate majority even though they represent only 18 percent of the American population." If "democratic" vs. "undemocratic" is the test in the Senate, we'll be waiting for Kansas to cough up its seats to California.

And aren't the Democrats being just a little hypocritical now? They sure screamed when Republicans were holding up Clinton's judges.

Fair Point No. 2. As the Christian Science Monitor recently put it, there isn't much "partisan consistency in how the filibuster has come to be viewed." You hate the filibuster when you're in the majority; you love it when you're not. Nineteen Democrats tried to kill the filibuster in the mid-1990s, and fact sheets from Republican opposition researchers are overflowing with quotations from this Democrat or that expounding on the evil of the filibuster when it was a tool in the other side's hands. But the hypocrisy game can be played both ways: When Bill Clinton was president, Orrin Hatch and Bill Frist weren't exactly jumping up and down about each nominee's right to an up-or-down vote on the Senate floor.

So how is this going to play out?

No one knows yet. A group of senators in the middle are trying to work out a compromise: A handful of Democrats would agree to allow four of the seven stalled nominees to come to an up-or-down vote on the Senate floor and promise not to filibuster future nominees except in "extremely controversial" cases; in exchange, a handful of Republicans would promise to vote against the nuclear option. But the deal isn't done yet, and Frist appears to be unyielding: There has to be an up-or-down vote on every single Bush nominee or he's going nuclear.

Meanwhile, Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid on Tuesday seemed to be calling Frist's bluff. While Reid urged Frist to find a way around a nuclear showdown, he said: "I want to be clear: We are prepared for a vote on the nuclear option. Democrats will join responsible Republicans in a vote to uphold the constitutional principles of checks and balances."

It sounds like Reid thinks Frist doesn't have the votes.

Right. But that doesn't mean that Frist won't proceed anyway. He wants to run for president in 2008, and he wants the religious right at his side. People like Rush Limbaugh are now declaring that whether Republicans force a vote on the nuclear option -- not whether they get more judges confirmed -- should be a litmus test for the party faithful. So with the stars lined up like this, maybe Frist wins either way. If he calls for a vote on the nuclear option and wins, he will have brought home a victory for the religious right. If he calls for a vote and loses, he will have gone down fighting. And God knows, the religious right loves a martyr.

Shares