The senators came and went, came and went from John McCain's office Thursday. With all the TV cameras and their bright lights in the hallway, the comings and goings took on the white smoke, black smoke, cars-at-the-Kremlin feel of something big.

Maybe it was, maybe it wasn't.

As evening fell on Washington, the ever-growing group of senators gathered in McCain's conference room suddenly seemed close -- and then, just as suddenly, not so close -- to a deal that would avert the nuclear option and preserve the Democrats' right to filibuster judges George W. Bush will nominate in the future.

With the clock ticking, the Republican Senate leadership is amping up its rhetoric -- on Thursday, Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist aligned himself with an African-American preacher who equated liberal judges with members of the Ku Klux Klan -- and seems determined to hold at least a cloture vote on one of Bush's stalled judicial nominees on Tuesday. If Frist sticks to that schedule, the moderate Republicans working toward a deal to defuse the nuclear option will probably have to reach it by Monday night.

Walking into McCain's office Thursday evening, Sen. Susan Collins, a Republican from Maine, thought that she and the other moderates had time to spare. She predicted an agreement by the end of the night. But when she walked out of McCain's office an hour later, Collins said that a deal would have to wait until Monday, when senators return from previously planned weekend events. The process, she said, was "proving more difficult than we thought."

Likewise, Democratic Sen. Robert Byrd walked into McCain's office proclaiming that he and Republican Sen. John Warner had drafted a "nuclear shield" that "might prevent the nuclear option from ever being detonated." When he walked out, he was plainly disappointed that his colleagues had not yet embraced the plan. "Hope springs eternal," Byrd said as he slowly made his way back to his own Senate office.

It was a sentiment repeated by many of the senators leaving McCain's office, including McCain himself. As he walked to his car, the Arizona senator said the negotiations were "complex," and he made it clear that Byrd and Warner had added to the complexity. "The wonderful thing about senators is that they have a lot of good ideas," he said, more than a little sarcasm creeping into his voice.

Like the other senators who filtered in and out of his office, McCain was chary about providing any details about the agreement being discussed. However, its broad outlines are already well known. A handful of Republicans would deny Frist the votes he needs to go nuclear; in return, a handful of Democrats would clear the way for floor votes on some of the judicial nominees they're currently blocking and agree not to filibuster future Bush nominees, except in extraordinary circumstances.

With their proposed language, Byrd and Warner seem to have added an additional prong to the proposal -- a focus not just on how the Senate treats the judges Bush nominates but on the way Bush chooses those nominees in the first place. Democrats contend that Bush has ignored the "advise" part of the clause of the Constitution that allows the president to appoint judges with the "advise and consent" of the Senate. Saying that he wanted the Senate involved in both the "takeoff and the landing" of judicial nominees, Byrd hinted that the Byrd-Warner language would suggest that the Senate Judiciary Committee create panels of academics and sitting judges that would identify "pools" of mainstream judicial nominees from which the president could choose. The proposal wouldn't require the president to pick from those pre-selected nominees, Byrd said, but he'd have an easier time getting his judges confirmed if he did.

It's hard to believe that the White House would be particularly excited about such a proposal, but McCain -- who embraced Bush in the 2004 election but isn't exactly the president's best friend -- indicated that he wasn't particularly interested in what the White House thinks. Asked if the Bush administration had involved itself in the negotiations over the nuclear option, McCain told Salon: "No, no, no, and nor would we anticipate that. This is a Senate issue."

Still, there was some concern that holding a deal over until Monday might give the White House, the Senate leadership or right-wing advocacy groups time to sway moderate Republicans from a compromise. Earlier Thursday, Ohio Sen. Mike DeWine expressed fears about losing "momentum" if a deal wasn't reached Thursday night. Vermont Sen. Patrick Leahy, a Democrat, said that moderate Republicans were under "constant pressure" to join Frist in going nuclear. "If this were a secret ballot," Leahy told Salon, "the nuclear option would go down in flames."

But it won't be a secret ballot. Throughout the day, the Republican leadership made it clear that they would tolerate only one resolution to the debate over judicial nominees: up-or-down floor votes on every single judge Bush nominates, including the judges he'll eventually nominate for the U.S. Supreme Court.

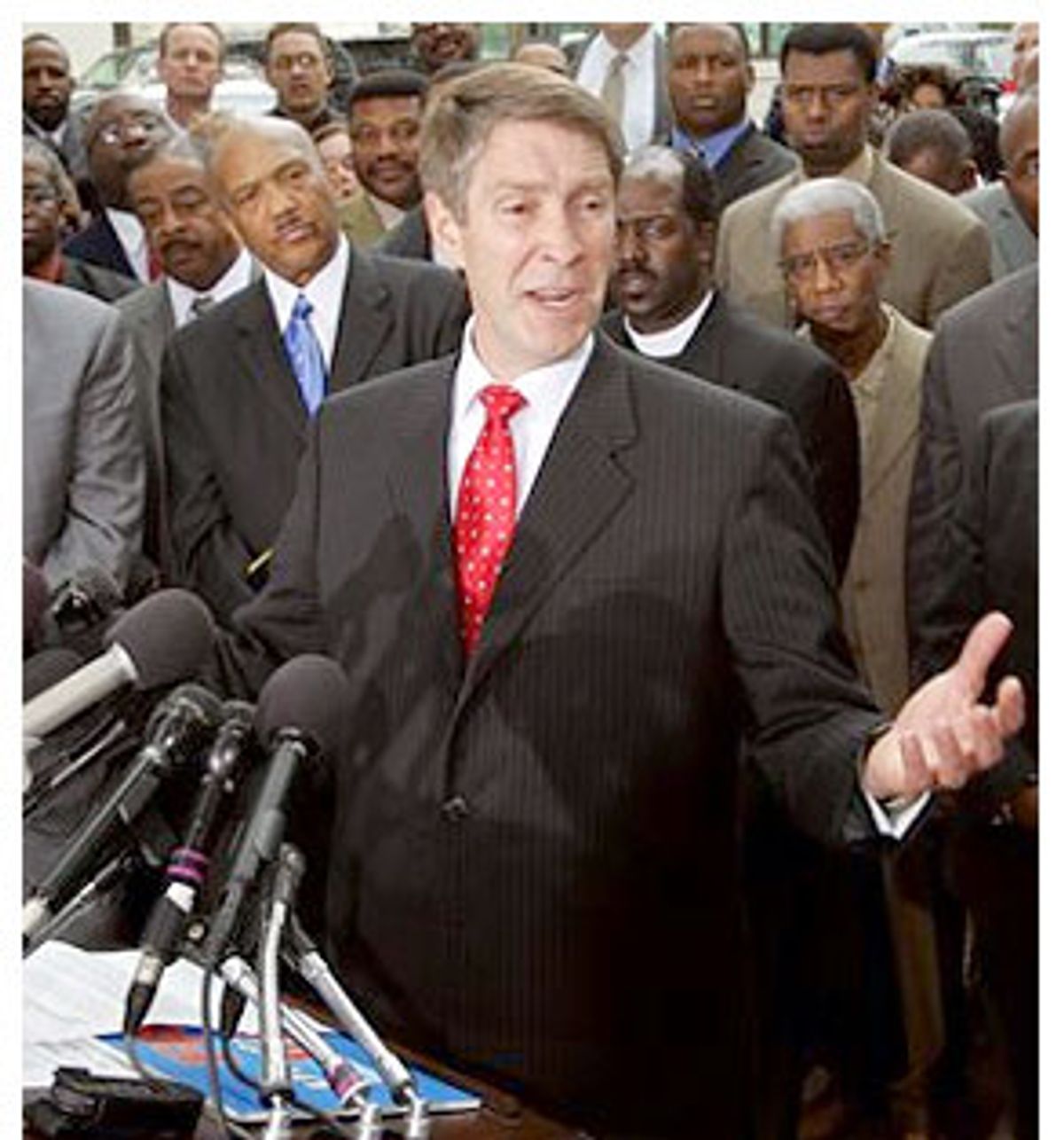

The notion of a "fair up-or-down vote" provided the theme for a rally that Frist's office helped organize in a park across the street from the Capitol. At the rally, meant to showcase support among African-Americans for Janice Rogers Brown, a California Supreme Court justice whom Bush has nominated to the U.S. Court of Appeals, Frist stood by smiling as Hope Christian Church Bishop Harry R. Jackson, Jr., invoked memories of the Ku Klux Klan and then referred to liberal judges on the bench today as "black-robed vigilantes" who have "taken away the true rights of an entire culture."

When Jackson was done speaking, Frist took his turn at the lectern. He did nothing to distance himself from Jackson's remarks; instead, he lashed out at Democrats for speaking in "uncivil" ways about Brown's judicial views. Asked a few minutes later whether the Senate majority leader thought it was appropriate to equate judges with Klan members, Frist's press secretary, Amy Call, snapped: "It's not like the Democrats haven't equated us with Ku Klux Klan members."

Earlier in the day, Call made it clear that the Republican leadership was unhappy with the way the debate over the judges was unfolding. On Wednesday and again on Thursday morning, New York Sen. Chuck Schumer took to the Senate floor to remind his colleagues and anyone watching on C-SPAN that, while Republicans routinely call the filibuster of judicial nominees unprecedented, Frist himself voted in support of a filibuster of one of Bill Clinton's judicial nominees in 2000.

Frist promised Wednesday to return to the Senate floor to address the apparent contradiction; he hasn't done so yet. When the subject came up at a press conference called by Sens. Pete Domenici, Ted Stevens and some of their Republican colleagues Thursday afternoon, Call pounced on the reporter who raised it. After trying repeatedly to distinguish Frist's filibuster from the ones he now opposes, Call complained that the press was "talking about one little vote" and trying to "catch us in all these little things."

And underscoring the divide between the Republican Senate leadership and the moderates who are working toward a compromise, Call complained that the media hasn't teed up the fight fairly for those who aren't wavering. Pointing to television talk shows that have pitted McCain as a representative for the Republicans, against a Democratic senator, Call said, "It's like, 'Well, where's our side?"

The Democrats don't have that problem. Although they remain united in opposing the nuclear option, they appear universally flexible in allowing up-or-down votes on at least some of the Bush judges they have previously blocked. While interest groups on the left won't be happy to see an Owen or a Rogers confirmed, they have their eyes on a bigger prize: keeping the filibuster around long enough to use it if Bush nominates a far-right judge to replace William Rehnquist on the U.S. Supreme Court. Thus Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid is free to encourage "responsible Republicans" to join Democrats in a compromise even as he pounds away at the Republican leadership.

As he has before, Reid reminded the Republicans Thursday that it will take only six of them to deny Frist the votes he needs to go nuclear. Sometime between now and Monday night, Reid and Frist both will find out if those six Republicans exist.

In the hallway outside McCain's office Thursday night, senators from both sides of the aisle suggested that, sooner or later, six Republicans will probably cross over. "I think there's still a good chance this thing will happen," said DeWine, a Republican. "We've made progress and you can see how a deal could be put together."

While the process was clearly taking longer than the senators had hoped, Nebraska Sen. Ben Nelson, a Democrat, said the extended negotiations were important because they gave senators time to develop the trust in one another that they'll need before feeling comfortable with an agreement that turns on undefinable concepts like "extraordinary circumstances."

As he headed home for the night Thursday, McCain said he agreed. "This whole thing is being conducted in an atmosphere of trust," he said. "We've just got to make sure that we get the wording right."

Shares