Rejecting the plans of their leaders and the demands of the religious right, seven Republican senators joined seven Democrats Monday night in a last-minute agreement to avert the nuclear option and preserve, at least in theory, the Democrats' right to filibuster future judicial nominees. The war over judicial nominees isn't over; it may well explode again this summer, when George W. Bush will almost certainly have a chance to nominate a Supreme Court justice. But Round 1 is done, and it goes to Senate tradition, the storied but seldom seen collegiality among senators -- and to the Democrats.

At a press conference just after the deal was announced, Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid -- who had repeatedly begged "responsible Republicans" to work with Democrats on a compromise -- said the agreement was "really good news for every American." Reid noted that he'd proposed similar deals to Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist over the last few weeks, but that the Republican leader had rejected them each time.

Frist himself tried to put the best face on things Monday night. Just a few hours after declaring that senators had a "constitutional responsibility" to provide up-or-down floor votes for every judge the president nominates, Frist struggled to explain how an agreement that will deny floor votes to two long-stalled Bush nominees might be spun as a victory for the Republican leadership. It didn't work, and Frist seemed to know it. After a brief floor speech and a hand-shaking photo op with Harry Reid, Frist all but raced out of the Capitol as he said, over and over, "Let's move forward." As Frist stepped outside and toward a waiting car, his press secretary, Amy Call, physically held a Capitol door closed to keep reporters from following him.

Asked whether Frist was going to have trouble with his base -- the evangelical Christians he'd been courting with an eye on the 2008 presidential campaign -- Call argued that it was Reid, not Frist, who was pandering to his base: "There should be some parity here in how we compare who's tied to what," she said. "That's all I'm saying."

It's true that no one knows for sure yet how either party's base will respond. Call pointed to the fact that, before the deal was reached Monday night, Reid was scheduled to appear in live TV spots paid for by liberal groups opposed to Bush's nominees. While those groups may not be thrilled that the deal struck Monday will allow floor votes on three Bush nominees many of them opposed -- Priscilla Owen, Janice Rogers Brown and William Pryor -- they can take comfort in the fact that the Democrats will remain free to filibuster two others, William Myers and Henry Saad, as well as future nominees when "extraordinary circumstances" arise.

If you were confused about which side won, it helped to look at who was angry at the deal. Focus on the Family's James Dobson called it "a complete betrayal," while Eli Pariser of MoveOn claimed victory. "President Bush, Bill Frist and the radical right-wing of the Republican Party have failed in their attempt at seizing absolute power and the 'nuclear option' is off the table," Pariser said in a statement. "Our members fought hard to preserve the filibuster, which will now live to see another day. The only way the 'nuclear option' comes back is if the Republicans break their agreement."

One source of lingering political confusion over that "agreement" comes from the fact that no one knows exactly what "extraordinary circumstances" means. The written agreement reached by the 14 senators says that each signatory must use "his or her own discretion and judgment in determining whether such circumstances exist." Ben Nelson, the Nebraska Democrat who, together with Republican John McCain, led the negotiations, told Salon that Myers and Saad could be seen as paradigm cases for judges whose nominations would have amounted to "extraordinary circumstances." But no one knows for certain how the standard will be applied. Republicans who signed that agreement told Salon that they never discussed particular judges -- either current nominees or ones Bush might name in the future -- in trying to define what "extraordinary circumstances" means.

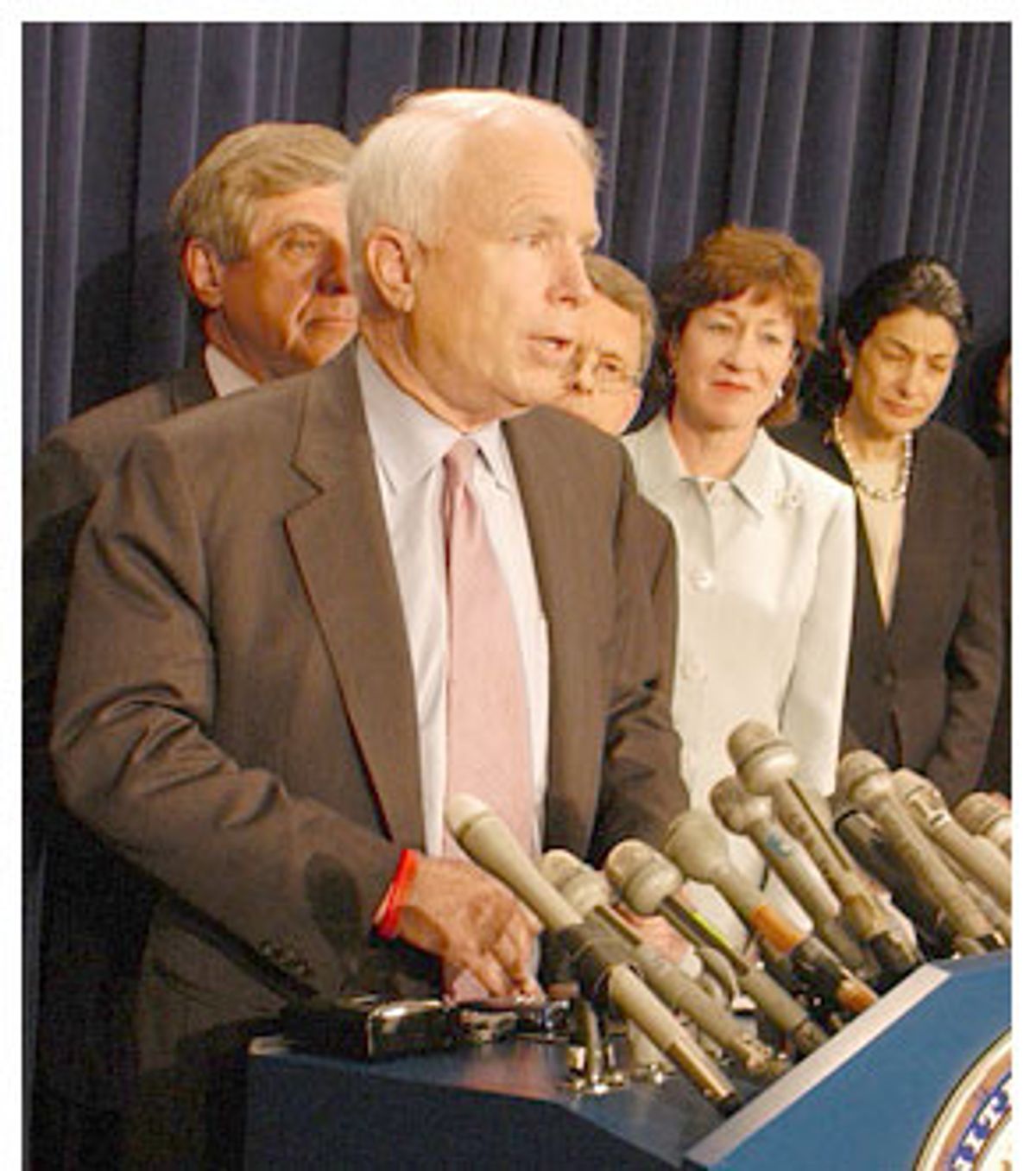

The definition is critical. If the Republicans who signed off on the agreement -- McCain, John Warner, Olympia Snowe, Susan Collins, Mike DeWine, Lincoln Chafee and Lindsey Graham -- believe that the Democratic signatories are filibustering future nominees who don't meet the "extraordinary circumstances" standard, they are free to push once again for the nuclear option. Frist warned that he'd be monitoring the agreement for "bad faith" and "bad behavior," and he made it clear that he'd be willing to push the Senate to the nuclear precipice once again if he saw signs of either.

Several of the Republicans who signed the deal echoed Frist's warnings. Ohio Sen. Mike DeWine stressed that, if the circumstances warrant, Republicans "reserve the right to do what we could have done" and invoke the nuclear option. One of the Democratic signatories, Mary Landrieu of Louisiana, seemed to acknowledge the fragile nature of the agreement, saying: "What we have come to is a pause, a hope, a chance that we can pass this difficult point."

For his part, Reid said he was optimistic that the agreement would keep the right to the filibuster alive, at least through the end of this Congress. Asked whether the parties might be right back to the edge once Bush nominates a replacement for the ailing Chief Justice William Rehnquist, Reid said that Senate Democrats didn't intend to "pick a fight" with Bush, but that Bush shouldn't "pick a fight with us, either."

Susan Collins and other senators involved in the deal suggested Monday night that it was never really in doubt -- that too many senators were too afraid of what the nuclear option would bring. Democrats were afraid it would destroy the Senate's tradition as a "cooling saucer," the place where debate outruns passions and minority views can moderate majority desires. Republicans feared that they might someday live to reap what they sowed, and that in the meantime Democrats could make their lives difficult by using Senate rules to slow legislation in the Senate to an agonizingly difficult pace.

Still, there were plenty of moments over the last week when a deal seemed unlikely. The negotiators seemed very close Thursday evening but were plainly discouraged as many of them departed Washington for the weekend Thursday night. When they returned Monday, senators on both sides of the aisle seemed convinced that a deal wouldn't come together. Early in the day, Colorado Sen. Ken Salazar said he thought the hopes for a deal were "remote."

Monday afternoon, the nation's longest-serving senator seemed resigned to the fact that the Senate had finally been lost. "I rise today to speak sadly," Democrat Robert Byrd said, and his words came so slowly that it sometimes seemed that he wouldn't have the strength to finish them. The 87-year-old Democrat looked out across the Senate floor. Ninety-nine mahogany desks sat empty, but not in his memory. "I can see Everett Dirksen as he stood at that desk," Byrd said. He could see Lyndon B. Johnson and Norris Cotton, Jacob Javits and George Aiken. Margaret Chase Smith was sitting in the front row to his right, just as she always had back then. "My heart is sad that it would even come to a moment such as this," he said. "Sad, sad, sad. Sad it is."

What a difference a deal can make. Just after 7:30 p.m. Monday, Byrd stood on a riser in a television studio just above the Senate floor, flanked by almost a dozen of his present-day colleagues, to celebrate the compromise that he helped craft, which he said had saved not just the Senate but the Republic itself.

It was easy to believe Byrd if you'd listened to some Republicans outline what would happen without the compromise. As Monday evening came, Frist briefed reporters on the steps he would take to pull the nuclear trigger: 'round-the-clock debate Monday night; a cloture vote Tuesday morning; a request for a point of order from Dick Cheney, sitting as the presiding officer of the Senate and the tie-breaker on a vote that might need one; an appeal by the Democrats; a tabling motion by the Republicans; the vote on the nuclear option and then a vote to confirm Priscilla Owen to the U.S. Court of Appeal for the 5th Circuit.

Then the questions began: Did Frist have the 50 votes he'd need to win? He said he didn't know. Would he have the vote of Arlen Specter, the Republican chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee who had previously called both the nuclear option and the alternative to it "mutually assured destruction"? Frist said he wouldn't presume to speak for another senator. Specter stood at his side, looking uncomfortable and saying nothing.

As Frist took questions from reporters, Senate staffers set up cots in the cloak rooms in preparation for a night full of debate. Aides wheeled in huge carts of food from Costco. John Kerry, leaving the Senate floor, offered a typically Kerry-esque assessment. Would his colleagues reach a deal? Kerry wiggled his hand in the universal sign for "50-50," then shrugged and said, "They could."

At about the same time, a dozen of the 14 senators who ultimately signed the agreement were gathering again in McCain's office in the Russell Senate Office Building, as they had been for hours before the prior week. They emerged close-lipped, promising to tell all at a press conference in the Capitol a few minutes later. But Salazar, a freshman senator who played a major role in the negotiations -- perhaps to make up to his colleagues for offering high-profile Democratic support for the confirmation of Attorney General Alberto Gonzales -- couldn't keep it quiet. As he boarded an elevator with Warner within ear shot of reporters, he said: "I think it's a good deal."

Minutes later, most of what had become the "group of 14" were riding together on the underground tram that links the Senate office buildings to the Capitol. McCain and Lindsey Graham were in the back seat together, smiling over a copy of the agreement McCain held in his hands. Graham would later say that he voted for the agreement because he couldn't stand the idea of causing devastation in the Senate at a time when the nation is at war and young men and women are still dying in Iraq.

For McCain, the impetus -- and the satisfaction -- might have been more personal. In leading his colleagues to a deal, McCain presided over a group of moderates and self-styled mavericks who suddenly see themselves as the road to progress in a polarized Senate. And he did so, coincidentally or not, at the expense of George W. Bush and Bill Frist, the man to whom McCain lost in the nasty Republican primaries of 2000 and the man McCain may face in the presidential primaries to come in 2008.

Shares