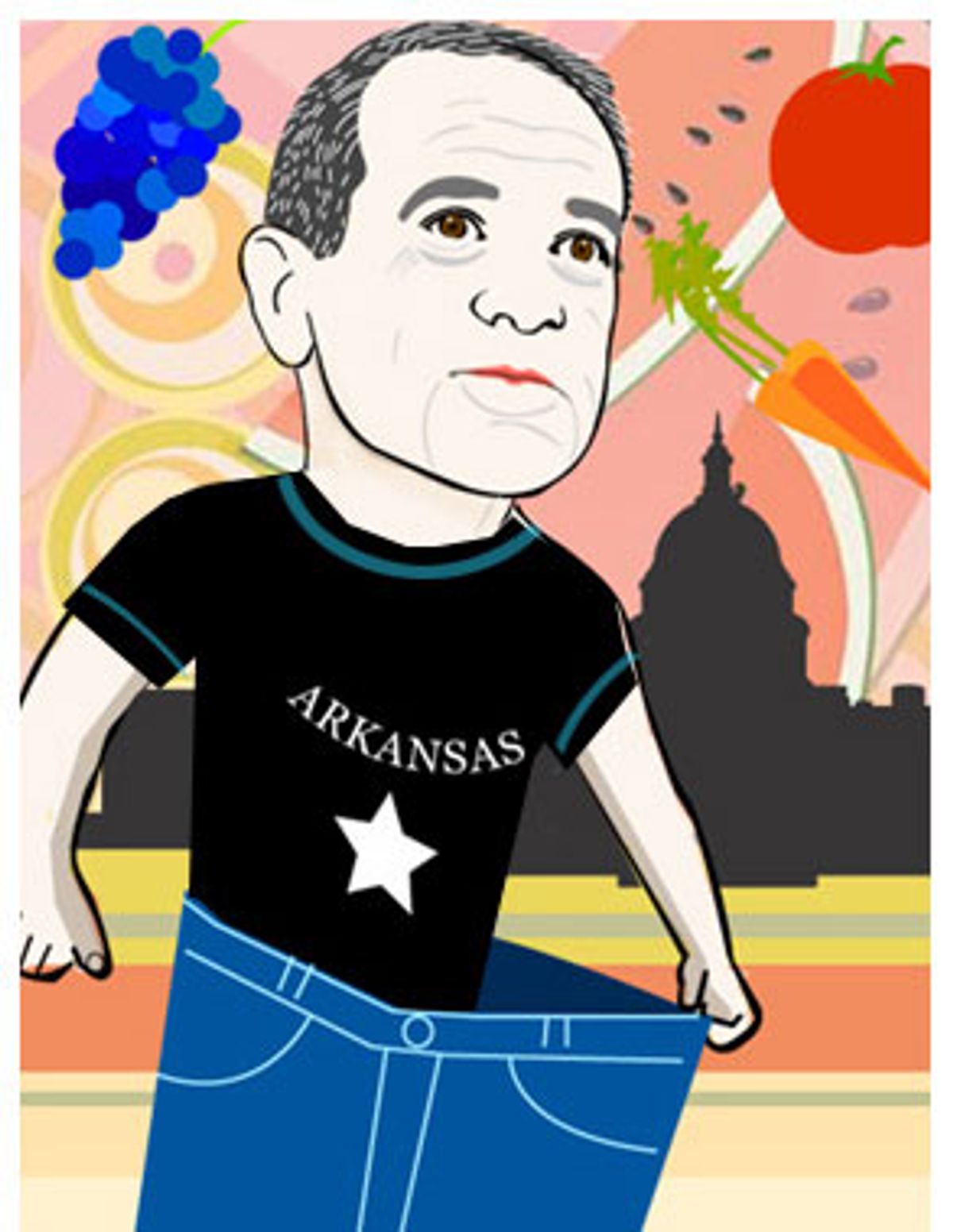

Gov. Mike Huckabee of Arkansas is the incredible shrinking Republican. The smaller he gets, the larger his national profile becomes.

The former Baptist minister, a conservative Republican who embraces covenant marriage, in the last few weeks has transformed himself into a national weight-loss success story, complete with "before" and "after" pictures. Since being diagnosed with Type II diabetes in 2002 and suffering a heart disease scare in 2003, the governor has drastically changed his diet (fried everything with an extra-large side of refined sugar) and his exercise habits (nonexistent). By getting religion about healthy food and fitness, he has lost 110 pounds, down from 280. He used to dread climbing the steps of the State Capitol to meet the press waiting for him at the top because he knew he'd be sweating and out of breath by the time he reached their microphones. Now slimmed down, he recently ran his first marathon.

In his new motivational book, "Quit Digging Your Grave With a Knife and Fork," Huckabee uses his own experience to try to inspire others to eat better and get off the couch. He inveighs against the plagues of transfat, refined sugars and highly processed foods, while extolling the virtues of whole-grain breads, fruits and vegetables.

If anything, Huckabee's book sets out to show that he feels the pudgy public's pain. He shares personal humiliations and his mantras -- like "stop whining," "stop expecting immediate success" and, above all, "stop sitting on the couch." He confides that he once made a ceremonious entrance into a room in the State Capitol, where 53 Cabinet-level agency directors all rose to stand in deference to their chief. But when Huckabee took his seat in the antique chair at the head of the table, the chair collapsed under his girth. He wanted to cry, he writes, but made a joke instead to cover up his humiliation. The supposed jolliness of fat people -- that's all just a defense to hide the pain inside, he says.

Earlier this month, Huckabee announced a nationwide initiative with former President Bill Clinton -- whose own recent quadruple bypass has made him seriously rethink his lifelong love of fried food -- to try to halt the rise of childhood obesity. Since then, Huckabee has been on a media blitz around the country, appearing in People magazine and on the "Today" show and "Good Morning America," to promote his book. The tour is raising speculation that by penning a diet book instead of the traditional candidate biography, he's trying to diet his way into the White House in 2008. After all, don't Americans care more about dieting than they do about politicians?

Arkansas had an 80 percent increase in obesity among adults from 1991 to 2002, and 61 percent of adults are currently overweight, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet it is taking some serious steps to fight the problem, too. The University of Baltimore's Obesity Initiative ranks Arkansas as one of the top states in the nation for its attempts to take on citizens' widening waistlines.

But some of those steps are controversial. For instance, public schools measure kids' body-mass indexes and send the results home to parents. While public health advocates applaud the state's first steps, they say they stop short of any actions that would potentially upset industry, like banning junk food in public school vending machines -- an idea that the governor opposes.

Huckabee, who'd run 4 and half miles earlier in the morning, spoke with Salon recently by phone from a hotel in the San Francisco Bay Area, a stop on his book tour.

What has been the reaction in your state to the initiative to measure kids' body-mass index in school?

There was this perception that we were going to line kids up in the hall, and say, "Here's a 160-pounder." When people understood the method of testing -- pinching with calipers -- and that these reports were going to be mailed confidentially and discreetly to parents, independent of the report card, it took a lot of the sting out.

We had a very small number of parents who reacted unpleasantly. A hundred to one, the reaction from parents was: "Thank you. We really weren't even thinking in terms of how much this could affect my child's future health."

As crazy as it may sound, the truth is that when a parent looks at 30 kids in a classroom, and they're all bigger than they were 30 years ago, they don't even see it in terms of "my child's overweight" because the frame of reference is skewed by the fact that [being overweight is] so universal. The BMI gives the parents something objective: "You know, we really need to be more thoughtful about the exercise our child is getting, and the food he or she is eating." It has really caused people to go to their pediatricians and say: "Give me some help."

What things has Arkansas done to help adults shape up?

We're trying to focus on giving people reasons and incentives to make healthier choices, as opposed to creating prohibitions and penalties. We offer $20-a-month discounts on health insurance to all state employees who do a health risk assessment. We had 18,000 state employees sign up in the very first enrollment period, a far greater number than we expected.

In the Arkansas Fitness Challenge, companies challenge other comparably sized companies over the course of a month to see how many employees quit smoking and how many steps they take, measuring them with pedometers. Over 400 businesses immediately contacted us to sign up.

One thing we kept hearing from people was: "I know we need to get out and walk, but I don't know where to go." So we compiled a list of every walking trail in the state, and it's constantly being updated.

We're trying to change the culture of health from one of disease focus to one of health focus. And we're looking at ways to change even more things. For example, it frustrates me that my own insurance plan as a state employee will pay for a quadruple bypass but will not pay for me to visit a nutrition counselor. That's crazy. The nutrition counselor might cost me $75 for a session that could save me from having the quadruple bypass.

Your initiative with former President Clinton calls for stopping the increase in childhood obesity in the U.S. by 2010. How are you hoping to do that?

We want to work with food companies to encourage them to promote healthier food choices. We realize that the food industry is at the mercy of the marketplace, and we're not blaming them for the fact that Americans are overweight. I certainly don't blame the fast-food industry for making me overweight. They sold what I demanded.

The second thing is to make more parents aware of how little exercise their kids are getting, and how many calories their kids are getting. Many of the things that parents do to show love for their kids are not necessarily in their best interest. For example, you take your kids to pizza not because you hate them but because you think that you're giving them a treat. And if a medium pizza might actually meet the nutritional needs of three or four kids, the large one shows that you have no limits to your love.

It's part of the whole culture of food. We let food become the reward. It's one of the most important things that I had to learn about why I'd never been successful in getting control of my health. I've heard people on talking-head shows chastising parents for overfeeding their kids and making parents feel terrible about it, as if they've done an abusive thing. And I want to just scream and say, "Obviously, either you're not a parent or you don't understand why parents are doing what they're doing. They're not doing what they're doing because they hate their kids.

There's not a parent in America that's saying: "Here, son, here's another 3,000 calories today. We'd like for you to be so fat that you have a heart attack by your 27th birthday."

So how do you hope to get parents to think about this in a different way?

A lot of it will be through the information we present in everything from public service announcements to trying to get doctors to put a new focus on [nutrition and exercise] when they talk to their patients. The entire community has got to become involved.

I liken it to the early '60s when Lady Bird Johnson led the Keep America Beautiful campaign. We had an incredible litter problem -- not that we still don't -- but it was so much worse then. People would just throw things out, and there was no social penalty for that. There was no sense of this is wrong. And through that awareness, people changed their image of litter.

The same thing has happened with tobacco. Whereas smoking once was considered glamorous and all the cool people did it, it's increasingly becoming something that is considered obnoxious. We don't tolerate it on airplanes. We insist on no-smoking rooms in hotels. Restaurants and workplaces are going smoke-free. By the same token, I think we have to change cultural attitudes about being overweight and about poor health.

Now, this is a tricky one because you don't want to go out and make people feel an extraordinary sense of shame and guilt.

You talk about that in your book -- how when you were overweight, you certainly knew that it was socially stigmatized.

It was one of my greatest personal points of pain. It wasn't like I didn't know that I was overweight. And it wasn't like I wasn't aware that people were disgusted with me over it. But the guilt trip did not help me get control of my health; it did not move me to action. That is going to be the dicey thing for us. But I think that instead of focusing on weight loss, you focus on health.

Americans are obsessed with weight, and that's the wrong obsession. It's ideal to have a body-mass index that's in the normal range, but I think that most any doctor in America will tell you that a person who eats well and exercises regularly but may be a few pounds overweight is much better off than the person who is skinny but eats junk food and is sedentary.

What do you see as the government's duty in taking on obesity?

I think a lot of it is to create incentive, to reinforce positive behavior rather than to prohibit hurtful behavior. And here's why: Americans just don't respond to being told by anybody, especially the government, what they can and cannot do. I think Prohibition proved that. We have to create an atmosphere in which people see that being healthy is in their own best interest, and where it's financially advantageous to them, whether it's the $20 a month off health insurance or something else.

We're working on a plan in Arkansas where employees would get points for healthy choices -- everything from not smoking, exercising and maintaining normal body weight all the way to wearing seat belts. And then we would reward employees with paid days off, and maybe even cash benefits, because if they're healthy, it's actually in our best interest.

In the governor's office, we're letting employees have up to 30 minutes a day, during work, for exercise and activity. We started it in our office [after] I realized that by letting state employees who smoked take smoke breaks, we were rewarding the wrong people.

Your book is really about inspiring people to find the motivation not just to diet but to adopt a healthier lifestyle permanently. But if individual motivation is the crucial thing, in your view, how can the government help?

The oath of Hippocrates was: "First, do no harm." The first thing the government can do is just not do any harm. And frankly, it does a lot of harm when it wants to start being the sugar sheriff or the grease police; if it moves this from a discussion on healthy behaviors to a point of taking over people's lives, it's going to lose the battle, because the American people will rebel.

If you start saying, we're going to tax cheeseburgers more than we tax lettuce, and we're going to charge every overweight person more to ride on the roadways because [they're] busting up the asphalt with [their] big fat rear, it's going to absolutely be a disaster. I know I was never motivated to change because someone tried to force me. It was the least effective thing when people would come up to me and tell me how fat I was and how hideous I looked. It may have made me angry, it may have made me wish I wasn't, it may have made me want to find out what airline seat they were sitting in and go sit beside them -- but it did not motivate me to change.

But public attitudes about tobacco have changed, and hasn't that partly been through higher taxes and all the government regulations about where you can and cannot smoke, as well as the lawsuits against the tobacco companies?

I think that it has to a degree. But there are two fundamental things that are different. No. 1, government has acted more as a response to public sentiment than it has in order to create public sentiment. Government acted only when enough people said: "We're sick of this. We want clean air. Enforce clean air."

And the second thing is that there are some unique things about tobacco that are not common to food. Tobacco is the only product that we legally sell that, when used according to the label instructions, is absolutely guaranteed to kill you. Whereas food is necessary to sustain life.

People have to eat; nobody has to smoke. And then the question is: How much is too much and who gets to make the decision? I think the city of Detroit talked about putting a special tax on fast food. But what's fast food? A few minutes ago I went down to the little market a few blocks from my hotel, picked up a spinach salad and brought it back to the room to eat it. Was that fast food? It was healthy. Should I pay a tax on it just because I got it at the delicatessen as opposed to fixing it at home? That's going to be a tough one. I don't think that they'll ever be able define it and make that work. Plus, I can go to McDonald's and get a very healthy meal; sometimes I get a salad there, and it's very good. I don't have to get three Quarter Pounders.

What kind of pressure do you think government should put on business to serve healthier foods? You talked about trying to encourage them to, but you also said that the food industry is just responding to the market.

Interestingly enough, I've had several visits with major food company CEOs in the last several months, and they're already gearing up in both their manufacturing and their marketing. Food companies know that the growth of the market is in healthier foods.

So you think that the public's attitude is shifting, and that's bringing the food companies along?

I do. More and more people like me are saying: "I'm looking at that label, and if it's got partially hydrogenated vegetable oil, back on the shelf it goes."

What role should the government have in deciding what food advertisers should be able to market to children?

I'm really a First Amendment guy when it comes to telling the media what they can do, because I don't want the government telling you what you can write. I'm almost a libertarian when it comes to things like that, much to the surprise of many, even though I'm a conservative Republican, and a person of deep personal faith. I am very uncomfortable when people want to start choosing even what's on the cable channels. Because you know, where does it stop?

There are a lot of things on television that are offensive to me, but that's why I have an off button. And when enough people like me are disgusted with something and don't watch it, then they'll be a different kind of program. The reason some programs are continuing to proliferate is because whether or not I particularly like it or agree with it, there are folks out there that enjoy it. Art typically reflects the culture rather than necessarily creates it.

You write in the book that you're opposed to lawsuits against food companies by people who believe that they've made them or their children fat. Why?

Because I think that that's basically based on the outright, reckless, irresponsible greed of lawyers, and people who refuse to accept responsibility for their own actions and want to make excuses and blame others. I strongly believe the people who are like me -- underexercised and overfed -- have to stop making excuses.

I can't go around whining all the time, blaming everybody else for the fact that I was overweight and in poor health. I was that way because I made bad choices. No one ever put a gun to my head and forced me back to the buffet for a second time.

One issue that's been a hot-button one in your state is whether junk food should be banned in schools. As I understand it, vending machines are now banned in elementary schools in Arkansas but not in the higher grades. Why not extend it to all students?

We have banned it for the elementary kids, and I think that's appropriate. These kids are so young that I don't know that they are at a point where they can make good choices or would make good choices.

We may eventually ban junk food for high school kids too. But right now we want that decision to be made at the local level, with input from parents and the schools. In some cases, schools have contractual obligations, and we don't want to disrupt that until those contracts are over. But we would like them to maybe look at not renewing restrictive contracts.

And we don't want to be driven by assumptions and hysteria. We want a research-based approach to improving health -- because the first time we do something that's reacting to even a legitimate assumption and a study comes out and says that it's not a factor, then I think we lose credibility.

With our BMI data, we're preparing a study now; we're going into our schools and forming test groups. Group 1 has unlimited access to vending machines with any kind of product they want, Group 2 has no vending machines whatsoever, and Group 3 gets vending machines, but the machines are filled with healthier options, like bottled water and juice. At the end of a year, you can see what has happened to the groups' BMIs. Did the access to those machines make a significant difference? I think we're going to find that it makes a slight difference, but most kids who are going to eat junk out of vending machines are [also] going to eat junk whether they bring it from home, go off campus to get it or just eat it after school.

A lot of people think: Just get vending machines out of the schools and make kids take P.E., and this whole thing is fixed. I don't think so. And here's why: Good health habits are more caught than taught. It has a whole lot more to do with the overall culture that a kid grows up with in his or her family than it does with just going to school.

Too many people want there to be a simple demon for why we're in the shape we're in, and there's not. They want to blame the fast-food industry, or they want to blame the schools. I don't think it's that simple. Plus, that view totally removes parents. Parents have to understand that the school cannot be the vicarious parent.

I'm afraid that we're creating this mind-set where a lot of parents drop their kids off at school like they're dropping laundry off at the dry cleaners, expecting to pick them up with one-day service and that everything is going to be just fine. That's totally unrealistic, and it's completely unfair to teachers and to school systems to be given that kind of burden. The schools ought to be a part of it, but the school cannot be a substitute mother and father.

Don't schools undermine what they're teaching about nutrition in the classroom by serving unhealthy lunches or having vending machines full of junk food available?

The school lunches do have to get better -- I don't disagree with that. I think every school needs to look at its menu. It's not that we'd say a kid could never eat a hot dog, but how many hot dogs should a kid eat? And should we fry foods in a school cafeteria? Maybe we should never fry foods there. We ought to serve more vegetables. When the USDA [U.S. Department of Agriculture] essentially ships in enormous amounts of subsidized food to schools, it's maybe not the healthiest thing in the world. I think that government has to begin to reevaluate that.

Some people have suggested that you're using your book tour to raise your national profile to run for president in 2008.

Well, I'm always flattered when somebody thinks that the primary reason I lost 110 pounds and got my health back is just as a political stunt.

That would be a very extreme political stunt.

Wouldn't it, though? In fact, I could even go further and say that the reason I gained 110 pounds and almost died was so that I could then have this resurrection. That would really be a great political stunt.

It's the nature of the public to assume that there's an ulterior motive to everything you do. But, quite frankly, whether I'm going to run or not, I don't know. I'm not being coy. I just simply don't know. But I'm not going to go around saying: "Oh no, I would never even consider it." If you get mentioned enough, and people keep talking to you, it's something that you might consider. But right now it's not something that's front and center on the radar screen.

The health initiative is. I really am very passionate about it. I think that it's an important thing. It may be more important than running for president.

In terms of the impact it could have?

Sure. I'm politically astute enough to know that just because I lost weight, started running and wrote a book about it, that's not singularly enough of a qualification to say: "Yeah, this guy ought to be president." Otherwise, Dr. Phil would be running; Oprah would be running. Actually, come to think of it, Oprah could get elected.

Shares