University of California at Davis geologist Jeffrey Mount and his geologist friends admit to being "natural disaster ghouls." For them, the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina is a chance to see geology in action, the changes wrought by the confluence of winds, waves, sediment, wetlands and drained tidal lands.

Not that Mount's taking it lightly. His sister lives in the French Quarter in New Orleans and evacuated to North Carolina. Her home isn't underwater because, Mount explains, the French Quarter was built on the natural levee of the Mississippi River. It's about 5 feet above sea level. But his sister doesn't know what will be left of her place when she gets back.

"Floods are my business," says Mount, who directs the U.C. Davis Center for Watershed Sciences. He's also a member of California's State Reclamation Board, which controls floods along the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Reached at his home in Davis, Calif., Mount describes why the levees in New Orleans are bound to breach again.

Why is New Orleans underwater today?

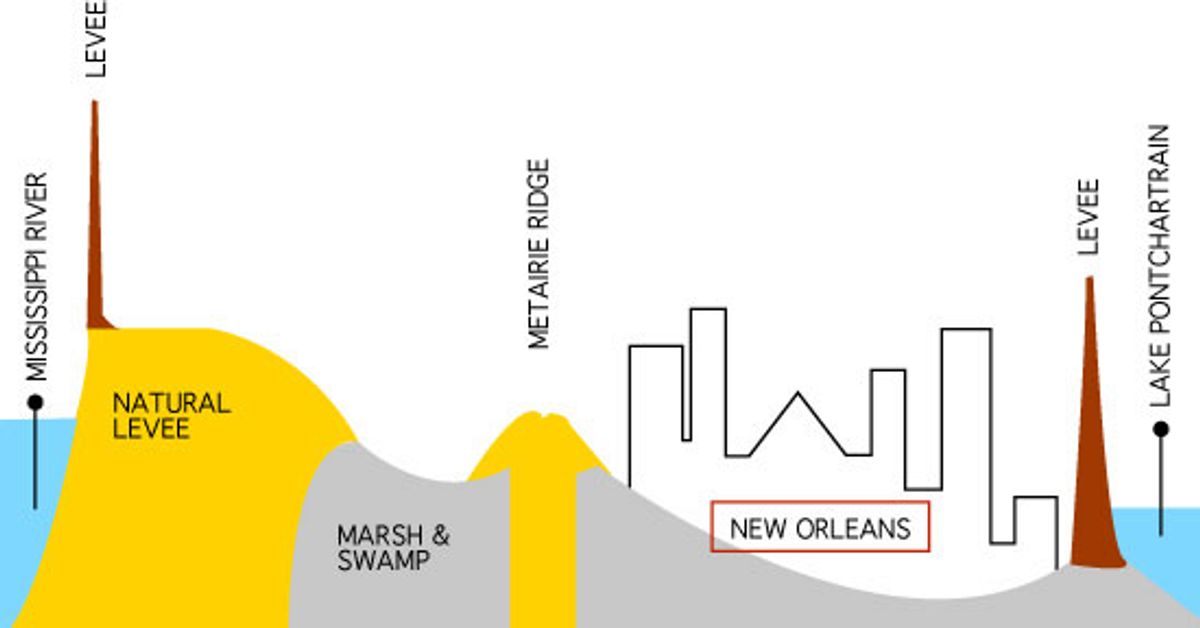

The problem is New Orleans is caught between two threats. One is the Mississippi River and the other is hurricanes. And it is in a bowl.

How was the bowl formed?

Geologically, it's an amazing thing. Imagine this massive river that has been dumping piles and piles of sediment into the Gulf of Mexico. Now, that mass of the sediment is so large it literally causes the earth's crust to sag underneath it. That is a natural process of subsidence. And every time a sag forms, the space is filled up by sediment. It fills it up because there is so much sediment coming down the Mississippi River. So these massive marshlands, or delta, where the river transports sediment into a standing water body -- the Gulf of Mexico -- basically stayed at sea level the whole time, even though the land was subsiding.

What is unique about the delta?

It's a combination of fresh and saltwater marsh but it's mostly freshwater. It's some of the most productive environments for birds and fish. The city was first built on the bits of high ground. And the high ground itself was built by the river, which was depositing sediment next to the river channel to form a natural levee. Originally, New Orleans was just a series of marshlands around the natural levee on the side of the Mississippi.

The French Quarter's on the natural high ground, right?

Yes, and I can tell you it ain't very high. High ground in New Orleans is relative. In developing the city, they leveed off the low-lying areas and pumped the water out. They leveed off and drained these wetlands, and then they built a city. And the city expanded in this bowl, and grew inside the bowl. They are in a constant battle with seepage. The pumps are going all the time, trying to keep the water out.

The first buildings were erected on the natural levees?

Exactly, above the tidal influence. So, the tide wouldn't inundate you every day, and you'd be at high ground. When the French showed up and tried to make a city there, they built levees that would surround the city, so they wouldn't be flooded all the time. These levees are wonderfully and carefully engineered.

However, there isn't an engineer who isn't totally aware of the risk involved in New Orleans. That's because when the water comes in, there is nowhere for people to go. You can't run to high ground. Most cities that are prone to flooding, whether it's Sacramento or St. Louis on the Mississippi, you can move to high ground during floods. You can't in New Orleans. There is no high ground. When you're up in a skyscraper in New Orleans, you can see forever.

And it gets even more complicated. When you levee off this city, the whole area is continuing to subside. That means you're not replenishing your marshes. So things continue to sink. Many of these reclaimed areas were already below sea level. They just stuck a levee up around them, and drained them, and built houses. Some places in New Orleans are 5 feet below sea level.

In the early days of the French, when the city was surrounded by marshlands, the hurricanes trashed the city because it didn't have these big levees. But when the hurricanes did come, the storm surges and windblown waves would be slowed by or absorbed by these tremendous marsh areas.

Now, the marshes are gone. Because what they did is levee the Mississippi River, which goes past New Orleans, all the way out into the Gulf of Mexico. And the sediment and water, which used to flow into these marshes, is now directed out into the gulf, bypassing the marshes. They put up levees to get ships up and down the river. It's a transportation corridor and you've got to keep the water deep. The way to keep it deep is to have the river scour itself, and the way you get the river to scour itself is to put levees up on either side, so the water gets real deep as it flows. The deeper the water, the more powerful it flows. But it also means that the wetlands, which are not being replenished by sediment from the Mississippi, are disappearing.

How exactly has the decimation of all these wetlands contributed to the disaster?

The conventional wisdom is that by removing all these marshes, you have eliminated a shock-absorber that absorbed a lot of the energy of hurricanes, and the waves generated by hurricanes. The waves would have to roll across marshes. Now, they roll across open water. That's conventional wisdom. The scientist in me, who is naturally skeptical about everything, is not so sure that in the end we're going to decide that was the case for New Orleans.

The hurricane was in the middle of a jog and it turned right at New Orleans. It went east of the city and created the most interesting, wicked complication. It basically created winds that blew northeast to southwest across Lake Pontchartrain, which is connected to the Gulf, which sits north of New Orleans. These waves were blown across Lake Pontchartrain, and the storm surge piled up water against the north side of the city, and that's where the levees failed.

I don't know how much of Lake Pontchartrain was a marsh beforehand. Until I know that, I can't really say: Was it really all loss of marsh or did we get unlucky?

Do you think it's crazy to have a major metropolitan area in a place like New Orleans? Should we rebuild the whole city?

Oh, I don't think we have a choice. If you could go back in time, you would say, "This is a crazy place to build a city." If you could go back in time, at the time the French were standing on the levee, looking around, and someone said, "Sacre blue! We're going to build a city here." You would say, "Fine, but keep it small." But then it became one of the most important commercial ports at the bottom of the Mississippi, the Midwest, and then the entire nation. So you've got to rebuild it. It's a vibrant, thriving, wonderful city.

Is it inevitable that this will happen again?

Yep. You could sit down right now and say we're going to design a new levee system, which will be stronger and more powerful. But you're designing it based on the conditions for today. But all the conditions are changing. The climate is changing. The ocean circulation patterns are changing. The city is subsiding at about 3 feet a century, and if sea level is rising at about 3 feet a century, that's 6 feet. You tell me what the long-term prospects are.

At the same time, the geologist in me says you just have to live with natural disasters and you can't engineer your way out of them. Even so, we sure as hell need to take another look at how we can evacuate people in and out of New Orleans when we know a hurricane is coming.

Isn't there something strange about people in California scratching their heads about New Orleans: "Wow, how could they get in this situation?" Who are we to say that?

Totally. We are the state that is waiting to fall down at a moment's notice from a major earthquake. We're definitely in the same kind of boat. We've concentrated our populations in the worst possible place, when it comes to natural disasters. Who are we to talk?

Our capital city is the most flood-threatened major metropolitan area in the country. Period. Sacramento has the highest flood risk of a major metropolitan area in the United States. So, hello! We've just gotten lucky. And we will lose the battle of the inevitable.

I laugh, only in a gallows humor sort of way, when people in California go: "How stupid are those people to build a whole city down there in a subsiding bowl." Huh? Been to Stockton?

Shares