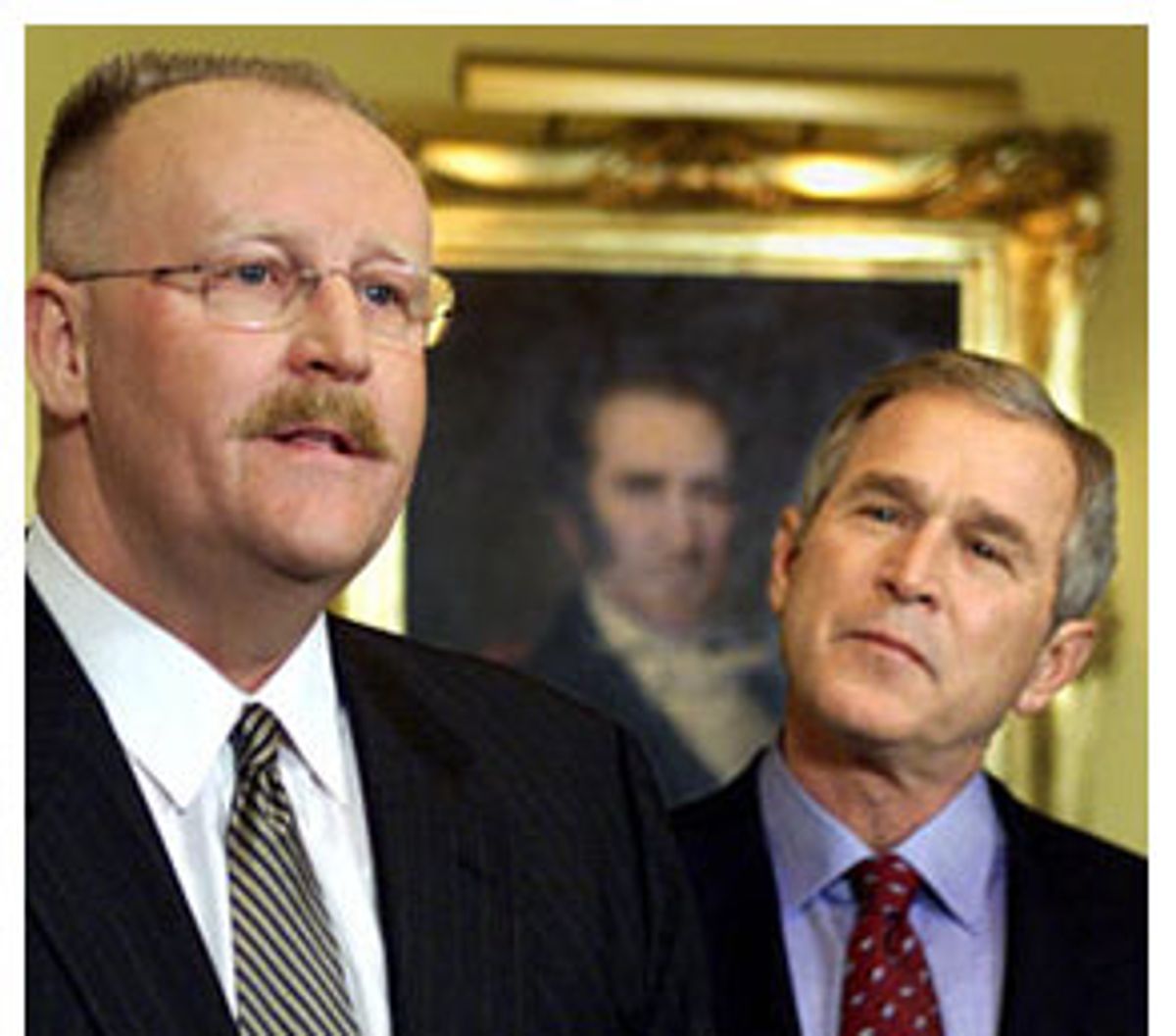

George W. Bush relied most heavily on three trusted staffers in his bid for the White House in 2000: political strategist Karl Rove, communications czar Karen Hughes and national campaign manager Joe Allbaugh, who had been Bush's chief of staff in Texas, when Bush was governor. The three were dubbed the "iron triangle" of Bush's top staff. Allbaugh was "the enforcer," says Texan Robert Bryce, the author of "Cronies," about Bush and the oil industry. "And he looked the part: crew-cut, cowboy boots, and just slightly smaller than a side-by-side refrigerator."

When Bush moved into the Oval Office, Hughes took a job as counselor in a spacious White House corner office with a view of the Truman balcony. Rove moved in as senior advisor. Allbaugh, on the other hand, went down the road to C Street in southwest Washington to take over the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

FEMA?

"Everybody thought [Allbaugh] was going to be White House chief of staff," Robert Novak said on CNN at the time. "And your initial reaction is, boy, what did he have against Allbaugh? But as I talked to politicians, they say this was a brilliant maneuver because FEMA is very important, politically, to any president dealing with disasters."

The FEMA director has turned out to have political consequences for the president all right, but not the kind that Bush supporters could have ever envisioned. Critics say Allbaugh hastened the decline of FEMA -- even before he turned the agency over to his buddy from Oklahoma, Michael D. Brown, the hapless captain when Katrina struck, whose political career appears to have been shipwrecked for good.

As for the president, a recent Washington Post-ABC News poll found that 54 percent of Americans disapprove of his response to Katrina. Allbaugh, meanwhile, has risen above the morass. He and his wife, Diane, now work as Washington lobbyists and consultants for such companies as Halliburton and Northrop Grumman, companies involved in homeland security and disaster relief that do business with the federal government.

When Allbaugh inherited FEMA in February 2001, the relief agency may have been in its best shape since its inception in 1979. It had been in the hands of James Lee Witt for the previous seven years. Witt was an experienced disaster manager who had been the director of the Arkansas Office of Emergency Services for four years before going to FEMA. Witt is credited with implementing sweeping reforms to speed disaster relief, and he was the first FEMA director to get Cabinet-level status -- and crucial access -- to the president. "Access to the president, I think, is critical in an agency like this," Witt told reporters over lunch just as he was leaving FEMA.

Bush, however, did not hand the FEMA reins to Allbaugh because of any long experience in emergency services. "Look at Joe Allbaugh's qualifications," says Eric Holdeman, director of the King County, Wash., Office of Emergency Management, who last month penned an editorial in the Washington Post, "Destroying FEMA." "He was campaign manager for Bush. He was a political strategist. He saw FEMA as a federal entitlement program for people. He had no interest in the mission and functions of the emergency management agency."

However, at FEMA, Allbaugh led federal rescue efforts at Ground Zero with apparently good results, though New York City officials, notably Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, got most of the attention. Allbaugh could also move fast. In February 2001, the Nisqually earthquake in Washington state occurred at 11 a.m. By 11 p.m., Allbaugh was in the Puget Sound area, leading a $157 million response.

Following the terrorist attacks on 9/11, Allbaugh backed plans to fold FEMA into the Department of Homeland Security. "I fully support FEMA's transfer into the new department and commit myself to ensuring its success," Allbaugh told the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee in September 2002. "This is the right action, at the right time, for the good of the country."

In March 2003, FEMA was folded into DHS. FEMA critic Holdeman explains that the move stripped the FEMA director of Cabinet-level status, buried the agency in red tape, and caused key talent to flee. DHS employees now rate it as one of the worst places to work in the federal government, according to a nonprofit agency's report, "Best Places to Work in the Federal Government," released this week. "FEMA first became ill with the appointment of Joe Allbaugh," Holdeman says. Not only is it on the back burner of DHS priorities, he says, "it is not even on the stove."

After FEMA's move to DHS, Allbaugh promptly left the agency. "I have been a longtime advocate for the Department of Homeland Security, and now that it is a reality and the president has a great team in place, I feel I can move on to my next challenge," he said in a statement. Of course, before he drove off, he appointed the now infamous Brown as team leader, whom he had brought to FEMA in 2001 as general counsel. Appearing before the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee in June 2002, Brown said: "My friend, Joe Allbaugh, whom I have known for some 25 years, has asked me to serve with him. Our friendship goes back many years."

Allbaugh graduated from Oklahoma State University in 1975, the same year Brown moved from Southeastern Oklahoma State University to the University of Central Oklahoma. (It has been incorrectly reported that Allbaugh and Brown were college roommates. They did not attend the same college and were never college roommates.) Both were active in Oklahoma municipal or state government. Allbaugh was once the Oklahoma deputy secretary of transportation, and Brown was the staff director of the Oklahoma Senate Finance Committee from 1980 to 1982.

Patti Giglio, Allbaugh's spokeswoman, says Allbaugh is unavailable for interviews. She says that she is not sure exactly how Allbaugh and Brown met in Oklahoma, but that Allbaugh is "absolutely" responsible for first bringing Brown to FEMA. "He hired him because he was a solid attorney with a strong ethics background," she says.

Like Allbaugh himself, Brown was no veteran of emergency services. He worked as general counsel for Dillingham Insurance in Enid, Okla., from 1988 to 1991, and evaluated judges for the International Arabian Horse Association for the 10 years ending in 2001.

Brown's sole piece of emergency experience before FEMA came in the 1970s, working for the city of Edmond, Okla. In the spring of 2002, Brown delivered written biographical materials to a Senate panel considering his nomination to FEMA as a political appointee. In those papers, Brown said he worked as "Assistant City Manger, Police, Fire & Emergency Response," in Edmond from 1975 to 1978. He signed an affidavit stating that his biographical material and written answers to that Senate panel were "current, accurate and complete."

However, Edmond city spokeswoman Claudia Deakins says city records list Brown as an "assistant to the city manager" -- as opposed to "assistant city manager" -- from August 1977 through September 1980. Randel Shadid was on the Edmond City Council from 1979 to 1991 and was mayor from 1991 through 1995. He says he remembers Brown and described the Edmond job as relatively low level. "My best I can recall he was an assistant to the city manager, which basically means he did certain tasks for the city manager," he says. "He would not have been in charge of the police and fire departments. We had a fire chief and a police chief."

Shadid says Brown may have assisted the city in preparing a response plan for a tornado or a freight train spill. "He was a nice guy, hard worker and pretty bright," he says. "But the scope of doing anything in the city of Edmond is nowhere near the scope of trying to handle what's going on in the gulf."

Today, with the disgraced Brown having quit FEMA, and President Bush's post-Katrina poll numbers sinking, Allbaugh continues to prosper. His stint at FEMA has proven to be lucrative for him and his wife Diane, who are lobbyists and consultants for the Allbaugh Co.

A review by Salon of lobbying registration records shows that seven months after Allbaugh left what was to become the Department of Homeland Security, Diane Allbaugh registered as a lobbyist with three companies to work on homeland security or disaster relief issues. Prior to that, she focused almost exclusively on energy companies and electric utility clients.

Records also show that Diane Allbaugh contacted DHS for undisclosed reasons on behalf of two of those clients. She did less than $10,000 of work for each company and all three contracts were terminated in the summer of 2004.

Washington is full of folks in power with spouses who are lobbyists. Allbaugh's spokeswoman, Giglio, points out that Diane has her own substantial credentials as an attorney and a lobbyist. "Her work is much broader than 'electric utility lobbyist,' as you have described it," Giglio says in an e-mail. "She is an experienced government affairs consultant across many industry sectors."

Federal ethics law bars senior employees from contacting their former employers on business matters for a period of one year. But not necessarily their spouses. Scott Amey, general counsel at the Project on Government Oversight, says it is unclear if Diane violated any of a complex web of ethics laws, but there are provisions intended to prevent the use of spouses to skirt restrictions.

It is not the first time Diane's lobbying could be perceived as cashing in on her husband's connections. Then-governor Bush in 1996 learned from a report in the Dallas Morning News that Diane had been hired by Texas utility companies who had business before the state. Diane and Joe Allbaugh had moved to Texas from Oklahoma because Joe had become Bush's executive assistant. The paper said Diane could get $250,000 from the companies, even though she "had no previous experience with Texas legislators." Diane later dropped the clients to avoid the "perception of a conflict," she wrote Bush's general counsel.

This year, the Allbaugh Co. registered to lobby for Halliburton Co. subsidiary Kellogg Brown & Root, Northrop Grumman Corp., and Shaw Group, according to lobbying registration forms. In all three cases, the Allbaughs said they would "educate Congress" on either homeland security or disaster relief issues on the companies' behalf.

The Washington Post reported last week that Allbaugh was in Baton Rouge, La., helping his clients get business in the wake of Katrina. Allbaugh told the Post that he guides his clients toward "entities" that might need their services but, he said, "I don't do government contracts."

Press reports show that Kellogg Brown & Root received a $30 million contract to rebuild Navy bases in Louisiana and Mississippi, and Shaw got a $100 million FEMA contract for housing construction and management. Giglio says Allbaugh had nothing to do with those contracts at all. "He is not in the government contracting business," she says. "Everybody is trying to connect the dots. They just don't connect. He did not secure these contracts for either of these companies."

Watchdog Amey says Allbaugh clearly got the job at FEMA because he was a political operative and he appears to be cashing in on his FEMA post now. "Bush may have stacked the [FEMA] administration with people who may not have been the most qualified, and who then steer business their way afterward. Cronyism gets them into the White House. The revolving door gets them business."

Shares