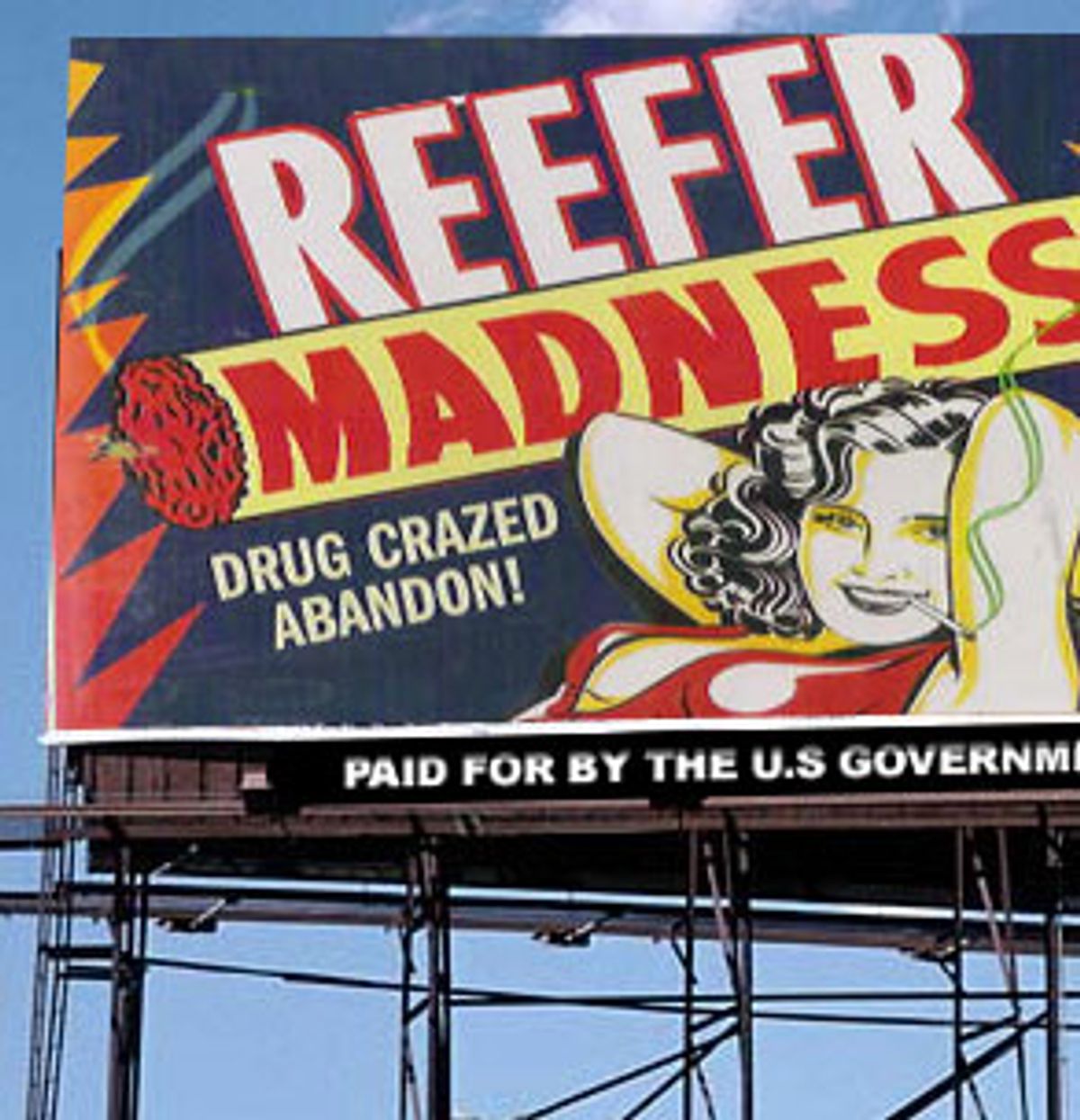

Parents who read the New York Times or Newsweek this past summer could be forgiven for freaking out when they came across a full-page ad warning them about the effects of marijuana on their teenagers. If the kids were off somewhere sparking up a joint, the federally funded message seemed to say, they were at risk for severe mental illness. Were those parents hallucinating, or was Reefer Madness, long since debunked, suddenly a real problem to be reckoned with?

The latest salvo in the never-ending war on drugs, the ads, which also ran in magazines like the Nation and the National Review, bore a stark warning. Under the headline "Marijuana and Your Teen's Mental Health," the bold-faced subhead announced: "Depression. Suicidal Thoughts. Schizophrenia."

"If you have outdated perceptions about marijuana, you might be putting your teen at risk," the text went on. It warned that "young people who use marijuana weekly have double the risk of depression later in life" and that "marijuana use in some teens has been linked to increased risk for schizophrenia." It followed with the sneering question, "Still think marijuana's no big deal?"

The rhetoric is alarming. But the research data used to support the ad campaign is hazy at best. Though carefully worded, the campaign blurs the key scientific distinction between correlation and causation. The ad uses some correlations between marijuana use and mental illness to imply that the drug can cause madness and depression. Yet these conclusions are unproven by current research. And several leading researchers are highly skeptical of them.

Scare tactics in the war on drugs have been around at least as long as Harry J. Anslinger, the federal drug warrior of the 1930s famed for his ludicrous pronouncements about the dangers of marijuana. But they're widely regarded as ineffective in deterring teen drug use. In fact, some research suggests they may actually increase experimentation. If anything, experts say, the latest ad campaign's overblown claims could damage credibility with teens, undermining warnings about other, more dangerous illicit substances. With medical marijuana a matter of renewed national debate, and with evidence emerging that there may be no connection between marijuana and lung cancer -- a key strike against the drug's use in the past -- the government's new campaign smacks more of desperation than science.

Spearheaded by the Office of National Drug Control Policy, better known as the "drug czar's" office, the ad campaign ran in print during May and June; it continues today on the federal government's Web site, Parents: The Anti-drug. There are plans to roll out more print, television and radio ads, according to an ONDCP spokesperson, if Congress approves the agency's current $150 million appropriations request this month.

At the press conference launching the mental illness campaign in May, the Bush administration's drug czar, John Walters, emphasized, "New research being conducted here and abroad illustrates that marijuana use, particularly during the teen years, can lead to depression, thoughts of suicide, and schizophrenia."

While the launch was attended by a former director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the current occupant of the office, Dr. Nora Volkow, did not attend or speak, nor did her deputies. This is unusual: The National Institute on Drug Abuse is the federal agency responsible for scientific research on the medical effects of drugs, so a campaign about marijuana's health effects would ordinarily feature at least one top representative discussing the science. The agency's name does not appear on the list of organizations endorsing the ad.

David Murray, special assistant in the drug czar's office, says that the National Institute on Drug Abuse was "involved in every aspect" of the planning of the campaign and "cleared and vetted" the statements in the ad and on the Web site. He says the drug czar's office didn't want to include more than one federal agency in the endorsements, adding that Volkow was out of the country at the time of the launch.

"Our research provides most of the evidence undergirding the campaign and we certainly support its goals," says Dr. Wilson Compton, director of the Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Research at the National Institute on Drug Abuse. But Compton concedes that the findings cited in the ad are "not completely established" and that experts consider them "controversial" and worth further investigation.

According to Murray, the latest available data shows that the consumption of cannabis is a key risk factor for the development of serious mental illness. With regard to schizophrenia, the campaign cites one study of nearly 50,000 Swedish soldiers between the ages of 18 and 20, published in the British Medical Journal in 2002, which found that those who had smoked pot more than 50 times had a rate of schizophrenia nearly seven times as high as those who did not use marijuana at all.

The American Psychiatric Association is one of the major groups backing the campaign; a spokesperson referred to part of the group's policy statement as the reason for its endorsement: "The American Psychiatric Association is concerned and opposed to the use of drugs and alcohol in children."

Yet leading experts in psychiatric epidemiology (whom the APA recommended contacting, but who do not officially speak for the organization) are far from convinced about causal connections between marijuana and serious mental illness. One key problem, they say, is that it's very difficult to determine whether pot smoking predisposes people to schizophrenia or whether early symptoms of schizophrenia predispose people to smoking pot -- or whether some third factor causes some people to be more vulnerable to both.

In the Swedish study, for example, when factors already known to increase risk for schizophrenia were removed, such as a childhood history of disturbed behavior, the connection between marijuana use and risk for the disease was substantially reduced. Just one or two additional unknown influences could potentially wipe out the apparent marijuana-schizophrenia link, according to Dr. William Carpenter, a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Maryland. Carpenter noted in a letter published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in October 2004 that the same genes that predispose someone to schizophrenia might also predispose them to substance abuse, but that drug use might start earlier simply because many people start using drugs in their teen years, while schizophrenia most commonly begins in the early 20s.

Perhaps the strongest piece of evidence to cast doubt on a causal connection between marijuana and schizophrenia is a long flat-line trend in the disease. While marijuana use rose from virtually nil in the 1940s and '50s to a peak period of use in 1979 -- when some 60 percent of high school seniors had tried it -- schizophrenia rates remained virtually constant over those decades. The same remains true today: One percent or fewer people have schizophrenia, a rate consistent among populations around the world. This is in stark contrast to studies linking tobacco smoking with lung cancer, where rises in tobacco use were accompanied by rising rates of lung cancer.

"If anything, the studies seem to show a possible decline in schizophrenia from the '40s and the '50s," says Dr. Alan Brown, a professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University. "If marijuana does have a causal role in schizophrenia, and that's still questionable, it may only play a role in a small percent of cases."

For the tiny proportion of people who are at high risk for schizophrenia (those with a family history of the illness, for example), experts are united in thinking that marijuana could pose serious danger. For those susceptible, smoking marijuana could determine when their first psychotic episode occurs, and how bad it gets. A study published in 2004 in the American Journal of Psychiatry of 122 patients admitted to a Dutch hospital for schizophrenia for the first time found that, at least in men, marijuana users had their first psychotic episode nearly seven years earlier than those who did not use the drug. Because the neurotransmitters affected by marijuana are in brain regions known to be important to schizophrenia, there is a plausible biological mechanism by which marijuana could harm people prone to the disorder. Both Brown and Carpenter say that people with schizophrenia who smoke pot tend to have longer and more frequent psychotic episodes, and find it very difficult to quit using the drug.

Of course, the U.S. government's current ad campaign targets a much broader population than those highly vulnerable to schizophrenia, fanning fears based on a statistically rare scenario.

The campaign also declares that today's pot is more potent than the pot smoked by previous generations, implying heightened risk. Fine sinsemilla may seem more prevalent than ditchweed nowadays, but there is debate over whether today's average smoker is puffing on stronger stuff than the average stoner of the 1970s, as Daniel Forbes detailed in Slate. And, as Forbes showed, the drug czar's office has grossly exaggerated the numbers on this issue in the past.

Meanwhile, UCLA public policy expert Mark Kleiman has pointed out that federally funded research by the University of Michigan shows that since the 1970s the level of high reported by high school seniors who smoked marijuana has remained "flat as a pancake." In other words, even if today's kids are smoking more potent stuff, they don't get higher than their folks did -- like drinking a few whiskey shots rather than multiple mugs of beer, they use less of the good stuff to achieve the same effect.

With regard to depression, evidence of a causal role for marijuana is even murkier. In general, depression rates in the population did rise sharply during the time period in which marijuana use also skyrocketed. But there were so many other relevant sociological factors that marked the last half of the 20th century -- rising divorce rates, the changing roles of women, economic shifts, and better diagnoses of psychiatric conditions, to name a few -- that scientists have rarely focused on marijuana as a potential cause for the increase in depression.

Murray maintains that scientists have simply overlooked marijuana in their search for explanations. One study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry in 2002, by New York University psychiatry professor Judith Brook and several colleagues, found that early marijuana use increased the risk of major depression by 19 percent. But that's not a substantial amount, according to Brook. And though the association remained after other factors were controlled for, such as living in poverty, it weakened further. "I wouldn't say that it's causal," Brook says. "It's an association. It appears to contribute."

The campaign selectively uses another piece of data, citing an Australian study published in the British Medical Journal in 2002 to assert that for teens, weekly marijuana use doubles the risk of depression. What that study found was that the risk doubled for teens who smoke marijuana weekly or more frequently. And it found that depression rates increased substantially in girls but not in boys. It also noted that "questions remain about the level of association between cannabis use and depression and anxiety and about the mechanism underpinning the link."

Moreover, a June 2005 study by researchers at University of Southern California, using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies' Depression Scale, found that marijuana use was in fact associated with lower levels of depression. Because the research was conducted using an Internet survey, it's possible that the most severely depressed people did not participate; nonetheless the study of more than 4,400 people found that both heavy pot smokers and moderate users reported less depression than did nonusers.

Dr. Myrna Weissman, a psychiatrist and leading epidemiologist of depression at Columbia University, sums up the current research and her view of marijuana's role in depression rates this way: "I can't imagine that it's a major factor."

The distortion of science under the Bush administration is, of course, nothing new.

"This is just more red-state culture-war politics," says UCLA's Kleiman, of the latest anti-marijuana campaign. He notes that since the government measures success in the war on drugs by a reduction in the number of drug users -- rather than by declines in drug-related harm or addiction -- marijuana is the obvious drug to go after. According to the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health from 2003, approximately 25 million Americans reported using marijuana over the previous year; compared with approximately 6 million users of cocaine and 1 million users of methamphetamine -- both far more addictive substances -- marijuana is a big, soft target.

Yet, for a public desensitized to fear-mongering antidrug messages, a campaign touting selected statistics from tenuous studies seems especially tone deaf, if not irresponsible.

"If I tell my 15-year-old that he's going to have a psychotic episode if he smokes pot, but he knows that his older brother already smokes pot and is fine, is he going to believe me when I tell him that methamphetamine damages the brain?" asks Mitch Earleywine, an associate professor of psychology at the State University of New York at Albany, who coauthored the USC study. Amphetamine psychosis is an established effect of taking large doses of that class of drugs; warnings about it appear on the labeling of prescription amphetamines. "What's going to happen," says Earleywine, "is we're going to lose all credibility with our teens."

The drug czar's office may soon face a full-blown credibility problem of its own regarding its fight against marijuana. Drug warriors have always had at least one powerful argument to fall back on when other attacks against marijuana seem to go up in smoke -- but in the face of a new study, that may no longer be the case.

Previous research has pointed to the notion that smoking marijuana could cause cancer, the same way tobacco smoking has been incontrovertibly linked with cancer and death. The Institute of Medicine, charged by Congress with settling scientific debates, said in its last major report on the subject in 1999 that the fact that most users smoke marijuana is a primary reason to oppose its use as medicine.

But that reasoning was called into question in late June, when Dr. Donald Tashkin of the UCLA School of Medicine presented a large, case-control study -- of the kind that have linked tobacco use with increases in lung cancer -- at an annual scientific meeting of the International Cannabinoid Research Society in Clearwater, Fla. Tashkin is no hippie-dippy marijuana advocate: His earlier work has been cited by the drug czar's office itself, because his research showed that marijuana can cause lung damage. The new study, however, found no connection between pot smoking -- even by heavy users -- and lung cancer. In fact, among the more than 1,200 people studied, those who had smoked marijuana, but not cigarettes, appeared to have a lower risk for lung cancer than even those who had smoked neither.

The new research has not yet been peer reviewed, but it appears congruent with earlier studies that found no link between marijuana and increased cancer risk. If the data holds up to further scrutiny and testing, one can only speculate what new ad campaign the drug czar's office might cook up. Marijuana may not make most people crazy, but this latest discovery could really drive the old drug warriors bonkers.

Shares