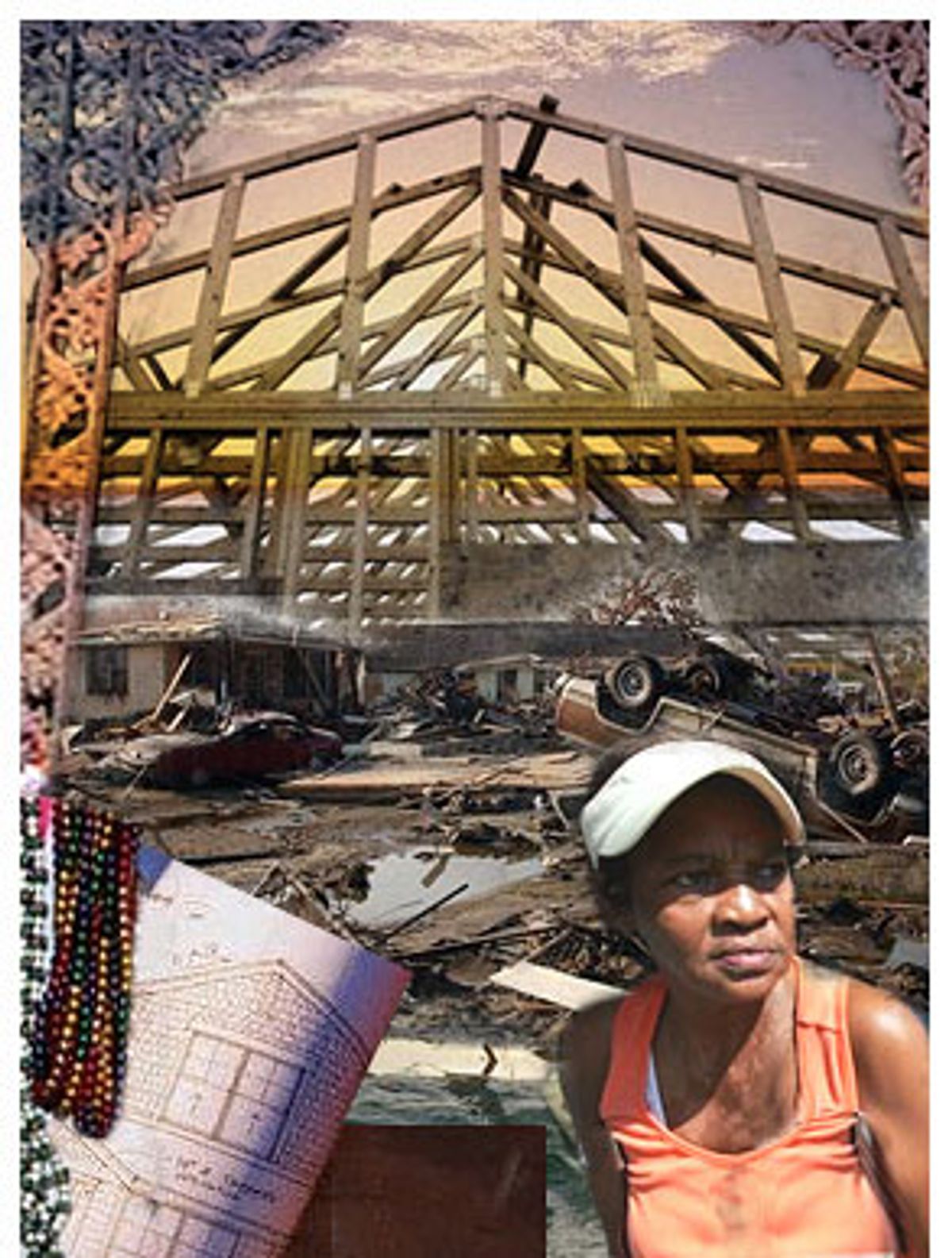

It's been four weeks since images of Americans devastated by Hurricane Katrina and abandoned by their government took over our television screens and our political discourse. Despite multiple opportunities for distraction -- the death of Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist, confirmation hearings on a nominee to replace him, John G. Roberts, even another major storm in the Gulf, Hurricane Rita -- the nation, to its credit, hasn't looked away. Thanks to Katrina, President Bush told a press conference Monday, "Americans saw some poverty they'd never imagined before."

Some Americans, of course, have done more than imagine it -- they've worked for years to understand and ease the crisis of poverty, and to untangle its grim synergy with race, which often paralyzes debate about its causes and solutions. At Salon, we were underwhelmed by the president's policy response to Katrina, much of which seemed like warmed-over Republican nostrums, heavy on tax credits, vouchers and help for "entrepreneurs," but light on big ideas on a scale that could make a difference to the hundreds of thousands displaced by Katrina, many of whom were already poor. Even the name, "Opportunity Zones," harked back to former GOP Rep. Jack Kemp's 1980s-era "Enterprise Zones" -- tax credits and business incentives that had little real impact on inner-city poverty.

But we were also unimpressed with the relative silence of the Democrats, who didn't seem to marshal an agenda to challenge or improve on the Bush Opportunity Zone approach. So we convened an e-mail panel of our own, a group of people working on poverty and opportunity issues from a range of institutions and ideologies, and threw them a set of questions about a real anti-poverty agenda in the wake of Katrina. Can Opportunity Zones work, and how? Are there better models from a new generation of anti-poverty efforts? Should evacuees return, or be helped to improve their lives wherever they landed? Should parts of New Orleans even be rebuilt at all?

The good news is there was some agreement, which in fact shouldn't be surprising. The conservative critique of government poverty programs summed up by Ronald Reagan's now-cliché "We fought a war on poverty, and poverty won" could have come from certain liberal critics of the programs, who had critiqued some of the same programs for putting money into bureaucracies and "professionals," while not necessarily making things better for the poor. Two decades after Reagan, there's broad agreement on several issues: that work is almost always better than welfare, that bureaucracies such as housing authorities are often a problem more than a solution, and that there's a strong positive role for the market. (And it's worth noting that while Bush has mostly ignored the issue of poverty, poverty "won" again on his watch, with the percentage of American poor climbing from 11.3 under President Clinton to 12.7 in 2004.

And while it's impossible to generalize about causes and solutions to poverty, the poverty of New Orleans especially evades easy answers. Certainly it's the result of segregation and racism; it's also been worsened by corruption that strangles the best efforts of community members and business owners at reform. It's also not a place where terms like "liberal" and "conservative" always make particular sense. We had a range of opinions on the panel, but they didn't always fit neatly into ideological categories. For instance, we started with the premise that the problem was "disinvestment," the flight of jobs and capital from New Orleans, but at least two of our panelists -- one a liberal, one a relative conservative -- corrected the question, noting there had been all sorts of investment in New Orleans, especially in public housing, but much of it had made things worse, not better.

There were other noteworthy observations. Everyone, even those whom most people would consider liberal, thinks tax credits and market incentives can work, if they're targeted well -- but there's a lot of concern the Bush administration's won't be. And while Republican House Speaker Dennis Hastert ignited a storm of protest when he suggested parts of New Orleans should not be rebuilt, there was surprising open-mindedness about what the shape of the remade city should be. (It was hard not to be open-minded when Rita flooded the Ninth Ward again as we began our conversation last Thursday.) Likewise, where only a decade ago there was often anguished debate about displacement and gentrification when many cities, encouraged by the federal government, replaced high-rise housing projects with low-rise, sometimes mixed-income developments, on our panel there was a lot of enthusiasm for trying to create mixed-income neighborhoods when rebuilding New Orleans, rather than just putting poor people back in their places. (There was one dissenter, and not for reasons you might expect.)

Everyone agreed on a couple of other things: that solutions to the problem have to be regional -- no city, especially New Orleans, can solve its poverty problems alone -- and that the wishes of those displaced should play a role in what our ultimate answers will be. But there was also plenty of debate, which you'll see unfold.

Andrew Leonard and I moderated the panel. Our panelists are busy people, and just when we thought we couldn't ask them to keep this debate going, they kept talking. In the spirit of open inquiry, we're going to publish the first part Wednesday, and run the rest Thursday. We'd love to hear from you, and we'll run a package of reader ideas and reactions on Friday. And we've opened a thread in our membership community Table Talk, for those who want to chat there. We'll keep the conversation going as long as there's interest, and we hope that's for a long time.

The panelists:

Angela Glover Blackwell is the founder and chief executive officer of PolicyLink, a nonprofit organization working to advance policies to achieve economic and social equity.

Angela Glover Blackwell is the founder and chief executive officer of PolicyLink, a nonprofit organization working to advance policies to achieve economic and social equity.

Xavier de Souza Briggs is a professor of sociology and urban studies at MIT and co-editor of "The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America."

Xavier de Souza Briggs is a professor of sociology and urban studies at MIT and co-editor of "The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America."

Craig Colten is a professor of geography and anthropology at Louisiana State University and the author of "An Unnatural Metropolis: Wresting New Orleans From Nature."

Craig Colten is a professor of geography and anthropology at Louisiana State University and the author of "An Unnatural Metropolis: Wresting New Orleans From Nature."

Edward Glaeser is a professor of economics at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Edward Glaeser is a professor of economics at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Howard Husock is a contributing editor to City Journal and the director of the Manhattan Institute's Social Entrepreneurship Initiative. He is the author of "America's Trillion-Dollar Housing Mistake: The Failure of American Housing Policy."

Howard Husock is a contributing editor to City Journal and the director of the Manhattan Institute's Social Entrepreneurship Initiative. He is the author of "America's Trillion-Dollar Housing Mistake: The Failure of American Housing Policy."

Bruce Katz is vice president and director of metropolitan policy at the Brookings Institution.

Bruce Katz is vice president and director of metropolitan policy at the Brookings Institution.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Forget Tourist New Orleans: Decades of disinvestment, racism, concentrated poverty and corruption made inner-city New Orleans one of the poorest, most dangerous and dysfunctional urban areas in America -- before Katrina. President Bush has proposed Opportunity Zones to rebuild the Gulf and New Orleans -- a package of tax breaks, tax credits, homesteading programs, etc., a response that's almost entirely reliant on the private sector and market incentives. Can any of it work, and how? Are there better tools, and if so, what are they?

And for extra credit: Do Bush (I) and Clinton-era Enterprise and Empowerment Zones offer lessons, cautionary or otherwise, or does the devastation of so much of New Orleans make comparison impossible?

Howard Husock

First, it's important to appreciate the essentially correct impulse underlying the Bush proposals. The physical rebuilding of New Orleans should not be our central focus. Cities -- and their built environments -- exist for economic reasons. "Disinvestment" in New Orleans was not a conspiracy of indifferent capitalists. It was a reflection of the city's failure to offer a healthy climate for investment. The combination of corruption and a failure to invest in essential public infrastructure let the oil industry, and much else, slip away to Houston. New Orleans ceased to be a magnet for new immigrants and those in search of opportunity went elsewhere, leaving behind "concentrated poverty," disproportionately supported by transfer payments.

The White House is correctly seeking to do what it can to make New Orleans an attractive locus for new investment. As for what kind, hard to say. Tourism, indeed, is not much on which to build an economy. Spinoffs from the port? Better commercialization of its deep and rich music culture (which is not just nostalgia)? One wonders what entrepreneurial ideas have been still-born in years past. So a low-tax, non-corrupt environment must be considered a crucial first step. Government clearly has infrastructure investments to make in flood control. But how far should that extend? Why not take the opportunity to make New Orleans a model for privately owned transit (sell off the ineffective bus system)? Why not sell off public housing rather than going the deeply subsidized Empowerment Zone/HOPE VI reconstruction route? Let the market decide what the highest and best use of that real estate is.

[Moderator's note: "HOPE VI" was an ambitious, $5 billion urban redevelopment plan launched during the Clinton presidency.]

The fact that the terminology (Opportunity Zone) of the president's proposal is reminiscent of President Clinton's Empowerment Zone does not mean the two are similar. The latter sought -- in the Model Cities tradition -- to rebuild specific buildings and corridors, and offered grants to city governments and "community" groups, generally staffed by professionals. A low-tax "free-trade zone" New Orleans would be a different matter, if that's really where we end up going. The political difficulty: no immediate ribbon cuttings.

Angela Glover Blackwell

Tax policies and market incentives have the potential to produce equitable outcomes, but the record is mostly disappointing or worse: crony capitalism, influential developers and businesses receiving the breaks without producing quality jobs or desirable housing and communities.

The few examples where they have worked the best operate on these principles and cautions:

Xavier de Souza Briggs

Angela has covered a number of the most important lessons, saving me the toughest part of this pop quiz. I'd add that while the evidence for luring businesses in with tax incentives is weak, tax credits can be powerful development tools in many other ways. The Low Income Housing Tax Credit, which Angela cites, is a key example. So is the concept of the New Markets Tax Credit, which has a much more limited track record. It provides a "kicker" to encourage private equity investments in development in economically distressed areas, lowering the upfront development costs in ways that really matter. It "softens" risk but doesn't remove it, which is healthy, from a good-government, good-market standpoint. So the main idea is that tax credits belong in the tool kit alongside grants and subsidized loans ("patient" or below-market capital). None is a panacea.

Most of the big lessons from the Empowerment Zones/Enterprise Communities are not about tax credits but about creating a success environment for a wide range of entrepreneurs, coordinating disparate functions in government (left hand/right hand stuff), and not pursuing fads of the hour, such as the idea -- popular in the mid-'90s -- that everyone in inner-city America is dying to be, and can be, a successful entrepreneur. Most low-income folks will get ahead through better jobs and training and by tapping proven supports, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, not by going into business for themselves (and everyone can think of exceptions to this).

A real Opportunity Zone would target workforce development just as intensively as business development, and we know how to do it right -- the skills development, job matching, transportation and child care and other enablers, etc. The same is true for turning contracting incentives (that focus on who gets selected) into real economic development, where clusters of businesses develop to raise the bar, raise the performance for multiple firms. This helps connect disadvantaged businesses to the wider regional economy. Much was learned about this after the L.A. riots, as businesspeople, researchers, planners and others worked on how to better connect the riot-torn areas to regional economic engines and networks.

Howard Husock

Xavier makes a number of good points, especially regarding workforce development. It's worth considering, however, what is specific about New Orleans that needs to be addressed, in contrast to low-income communities generally. And in creating a "success environment" we should keep in mind that local government plays a number of crucial roles. How difficult and/or how expensive was it to get a building permit in New Orleans? How often was it necesary to pay a bribe to do so? Similarly with business permits: How protracted is the permitting process from time of application to issuance of certificate of occupancy? Is New Orleans zoning appropriate or so draconian that variances and special permits are routinely required? How does the New Orleans tax rate compare to that of neighboring communities? All in all, don't forget local.

Bruce Katz

New Orleans has the opportunity to remake itself as a more competitive, vital and inclusive city. But that will require a much needed course correction on policy and practice. The starting point should be to get housing policy right. New Orleans did not just suffer from "decades of disinvestment"; the city actually suffered from "decades of investment" of the wrong kind. The neighborhoods of New Orleans hardest hit by the hurricane were, in part, "federal enclaves of poverty" -- an almost mini-museum of every federal housing program in play since the 1930s.

The concentration of subsidized housing in a few neighborhoods set off a devastating chain reaction in New Orleans. Over four out of nine poor black residents lived in neighborhoods of high poverty, where the poverty rate exceeded 40 percent. Such neighborhoods exact a huge price on families, consigning them to places where schools don't teach, jobs are scarce and crime takes a huge toll.

In rebuilding New Orleans, it would be tragic to repeat the mistakes of the past on housing. We have at our disposal a multitude of policy tools -- tax credits, vouchers, inclusionary zoning, regulatory reforms -- that can be used to build healthy neighborhoods and, at the same time, improve the lives of low-income families. Everyone involved in the rebuilding effort, particularly the federal and local governments, should adhere to one overriding goal: to create economically integrated "neighborhoods of choice" where families want to live rather than being forced to live. A mix of incomes will set in motion a virtuous cycle of functioning markets, attractive amenities, quality schools and other essentials of community life. The real issue now is not what to do, but who will lead.

Howard Husock

I couldn't agree more with Bruce that the many and various federal housing programs created their own poisonous brew in New Orleans. With that sobering history in mind, however, I cannot be sanguine about the prospects of success for the next version of same (mixed-income housing financed by tax credits, for instance.) We must not rule out the possibility that the problems associated with low-income housing in New Orleans were not owing to a so-called concentration of poverty but to the lack of individual ownership and poor management by either the government or not-for-profit groups. It is quite possible that a neighborhood of striving people of modest means can nonetheless be a good neighborhood, when supported with high-quality public goods (schools, parks, recreation). Large-scale construction of a new and better version of the Southern shotgun house (which, arguably, is what Habitat for Humanity is building), available for fee-simple ownership, strikes me as far better (and more practical) than another round of subsidized housing, even in a new flavor.

Bruce Katz

I think Howard's neighborhood vision is a reasonable one. But the president's urban homesteading initiative, to be frank, is not going to "get us there." The scale of the effort is just too narrow -- given the limited supply of federally owned land in New Orleans, the location of that land, and the need for additional subsidies to support construction and long-term ownership.

So here is another idea. In 2000, the president announced a home ownership tax credit program, modeled after the low-income housing tax credit program. The program, through the syndication of tax credits, could be a very efficient way to raise private equity for the development of large-scale, mixed-income communities of homeowners. The proposal has gained bipartisan support on Capitol Hill, though it has not yet passed the Congress. Why not put the tool to work in New Orleans -- a test pilot for the nation? I guarantee that it would catalyze the engagement of a network of housing practitioners -- builders, financial institutions, nonprofits, architects, homeownership counselors -- who can get the job done. We have the most sophisticated housing finance and development system in the world -- why don't we use it?

Howard Husock

I completely agree that the urban homesteading proposal is thin gruel, something someone came up with to dress up the "HUD homes for sale" advertisements that can be found in every Sunday newspaper. That said, I don't understand the commitment to the mixed-income approach. Where are the middle-class families going to come from? What would motivate their participation? Decent but simple new homes and the chance to own -- or even to rent from a resident owner -- is a far simpler matter and more likely to be sustainable.

Bruce Katz

We should also remember the Government Accountability Office's assessment of the empowerment zone program in 1999, which found that tax incentives were primarily used by large urban businesses, not the small businesses touted by the president in his Sept. 15 address.

Yet the Opportunity Zone idea -- and the whole concept of tax incentives in general -- ignores a central question: What is our collective vision of the New Orleans economy?

Before the hurricanes, New Orleans qualified as a classic low-road economy. Between 1970 and 2000, the share of jobs in the metropolis in manufacturing and transportation declined from 22 percent to 12 percent. Conversely, the service and retail sectors saw their share rise from 38 percent of employment to 52 percent of employment during the same period.

Such economic restructuring is common in the U.S., but it takes on a particular flavor in New Orleans. As everyone knows, New Orleans specializes in tourism-related industries, which generally pay less than the city and regional averages. (New Orleans has not emulated the Las Vegas model of high-road tourism, with decent wages, good benefits and built-in career ladders).

In addition, the metropolitan area does not specialize in the economically dynamic centers of high technology, new industries and innovation; it ranks 38th among the 50 largest U.S. metro areas on the Progressive Policy Institute's New Economy Index. Overall this is a weak market region that has continued to see employment declines in high-wage sectors: oil and gas extraction, chemical manufacturing, the port and related transportation industries, corporate headquarters.

The broad challenge for this region is, in short, to transition to a high-road economy that expands job opportunities for a broad range of the populace.

Opportunity Zones fall far short of the challenge -- and, to be frank, do not seem to even recognize the challenge before the region. Prior experience tells us that they will most likely aid some large businesses (i.e., the gaming sector) that are likely to stay in New Orleans anyway -- without doing much to aid the low-income workforce.

So, what to do?

Some ideas:

The feds, in short, can help New Orleans become a smart region that can better adapt to economic change and restructuring.

Joan Walsh, editor in chief of Salon

First, full disclosure: I'm on the board of PolicyLink, and I worked for the Urban Strategies Council when Angela ran it back in Oakland, Calif., in the late 1980s and early '90s. So I have a little bit of knowledge, which makes me dangerous. I just want to throw out a few follow-up questions to people:

I'm glad to see the general agreement around the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, but I'm trying to understand Howard's skepticism about using government incentives to create mixed-income developments. I think the "shotgun house" models Habitat is building are great, but why couldn't you also mix in some middle-income housing? It seems to me that rebuilding these neighborhoods with all or mostly poor people builds back in some problems -- namely, that neither the market nor the political system is sufficiently responsive to them. To have vital shops and businesses and schools would seem to me to require a mix of people. What am I missing?

Howard Husock

"Mixing in" the middle class sounds simple -- but becomes politically charged (if you're trying to build mixed-income housing in otherwise affuent areas) and logistically difficult if you have to recruit middle-class families to move to lower-income areas.

Joan Walsh

But hasn't it worked elsewhere? And aren't we talking, in New Orleans, about rebuilding in historically poor neighborhoods, so presumably there isn't the "not in my backyard" issue that comes with trying to push a "mixed" project on a wealthy area?

Howard Husock

But what's the point? In effect, a mixed-income development provides significant subsidy to households that could afford housing anyway -- in the belief that their example will somehow inspire their neighbors. Where's the large-scale evidence that that works -- and if not, why do it? I would argue that it is the desire to "move up" from a poorer to a more affluent neighborhood that helps motivate the poor to organize themselves and make good life decisions (work, save, marry). Thus, the so-called economic stratification of American neighborhoods strikes me as an important aspect of our social system that encourages upward mobility.

Angela Glover Blackwell

Type, cost and quality of housing are not the only factors that determine whether a neighborhood will thrive as a stable mixed-income community or struggle as an island of concentrated poverty and economic immobility. Make no mistake: The reality is that concentrated poverty does not create the desire to "move up," but rather hinders residents from doing so. Housing policies and forms of building are key, of course, but what makes or breaks neighborhoods are the combined qualities of public life: crime and safety, schooling, public spaces, transit and other infrastructure, local retailing, and so forth.

Successful mixed-income communities can take a variety of forms and will attract people of different incomes for different reasons. For example, comprehensive inner-city redevelopments like McCormack Baron Salazar's Murphy Park in St. Louis encompass affordable housing, good schools and transit to create a vibrant, livable community. Well-designed, transit-friendly, tax credit-financed affordable multi-unit housing developments have diversified the income and racial mixes of some San Francisco Bay Area suburban neighborhoods. A new "transit village" in a low-income section of San Diego, being planned by residents with support from the Jacobs Family Foundation, will incorporate a range of incomes and ownership strategies from the start that give generations of families an option to stay as their incomes may grow.

These and other approaches are certainly not easy or simple, but when well executed they meet a combination of market niches that one can envision to a greater or lesser degree in the New Orleans area. And if substantial amounts of land in New Orleans cannot be rebuilt on for safety reasons, then the higher densities for the available land for housing may necessitate that some of it be multi-unit rather than only single-family homes, even modest shotgun houses.

Howard Husock

There has never been more concentrated poverty in this country than the Lower East Side of New York, circa 1900. And yet the desire to move up and out was clearly strong; by 1930, settlement house leaders in the neighborhood observed that density had been replaced by "empties." It is not concentration of the poor per se that hinders upward mobility -- indeed, the desire to move up and out can be a strong one. But without the chance to own, save and then sell to realize gain, the poor are unduly hindered. This has been the burden imposed on them by public housing and other forms of subsidized rental. It is worth bearing in mind when considering the developments to which Angela refers that old-style public housing, too, was opened with great fanfare. Individualized ownership of small properties offers a far more secure route to long-term maintenance. I do agree, though, that these need not be single-family homes. Multi-family homes -- including some with rental units (with owner-occupancy encouraged) -- are a vital component of replacement housing, as well.

Xavier de Souza Briggs

Howard, I read our history differently. Poverty concentration has never been a "natural" condition of city life. Yes, those with the means tended to avoid tenement slums, and immigrants with few options tended to congregate in them. And yes, most Americans would agree with the idea of striving and incentives to encourage same. But it is very hard to look at the evidence on ghetto poverty neighborhoods and conclude that people lack motivation to leave them. Highly regulated markets make it hard for those people to afford to do so, and housing discrimination -- illegal under the law and also wrong -- makes it even harder.

A host of successful mixed-income developments demonstrate the demand by middle-income buyers, at least in tight urban markets, and subsidy to market-rate buyers is very minimal. The cross-subsidy mostly works the other way, to enable low- and moderate-income families to live in environments that people of means are also invested in. A demand study in New Orleans would be easy enough to do, and as Joan says, the central city's historic character gives one many options for effective design and marketing to a range of income levels.

Public housing used to be much more economically diverse, as you know. White families with employed heads fought to get in, because it was better than the old stuff it replaced. Likewise, subsidized or "social" housing is much more income mixed in other parts of the world -- not England, to be sure, but certainly in economically successful cities with high housing costs, such as Singapore.

Joan Walsh

Yes, I have to say that when I toured my Irish immigrant grandparents' neighborhood in the Bronx with my godfather about 10 years ago -- Highbridge -- it was clear that while it had been heavily Irish and immigrant in the '20s-'40s, there was some economic diversity -- local shopkeepers and neighbors who helped my grandparents and my dad and siblings when things were particularly tough. Gradually a Hibernian buddy got my grandfather into the steamfitters union, and they moved to the middle class. So ... the concentration and isolation of the urban poor has seemed to me something especially pernicious, as well as an unintended consequence, as Bruce points out, of bad social investment and social policy. I would think New Orleans offers a chance to bring people back in a different way.

Howard Husock

It's the hubris of "bringing people back in a different way" of which I'm deeply skeptical -- i.e., that an agency, choosing among applicants and issuing a Request for Proposals, can somehow find the right combination of people to mitigate what are said to be a concentration of poverty effects. As for the success of mixed-income projects, again, there remains a Potemkin Village-quality to them -- the planners' idea of what an ideal community should be. Sure, public housing once had a greater economic mix -- but that reflected the post-WWII housing shortage. Similarly, there has been a mixture in New York City -- but that reflected the high percentage of total housing stock which public housing comprises there. If we pave the way for modest homes for those of modest incomes, these can be one of the tools they can use to improve their own lives and forge their own communities.

End of Part I. Tomorrow: Republican Rep. Dennis Hastert provoked controversy when he questioned whether New Orleans should be rebuilt. But do Salon's panelists agree with him?

Shares