The panelists:

Angela Glover Blackwell is the founder and chief executive officer of PolicyLink, a nonprofit organization working to advance policies to achieve economic and social equity.

Xavier de Souza Briggs is a professor of sociology and urban studies at MIT and co-editor of "The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America."

Craig Colten is a professor of geography and anthropology at Louisiana State University and the author of "An Unnatural Metropolis: Wresting New Orleans From Nature."

Edward Glaeser is a professor of economics at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Howard Husock is a contributing editor to City Journal and the director of the Manhattan Institute's Social Entrepreneurship Initiative. He is the author of "America's Trillion-Dollar Housing Mistake: The Failure of American Housing Policy."

Bruce Katz is vice president and director of Metropolitan Policy at the Brookings Institution.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

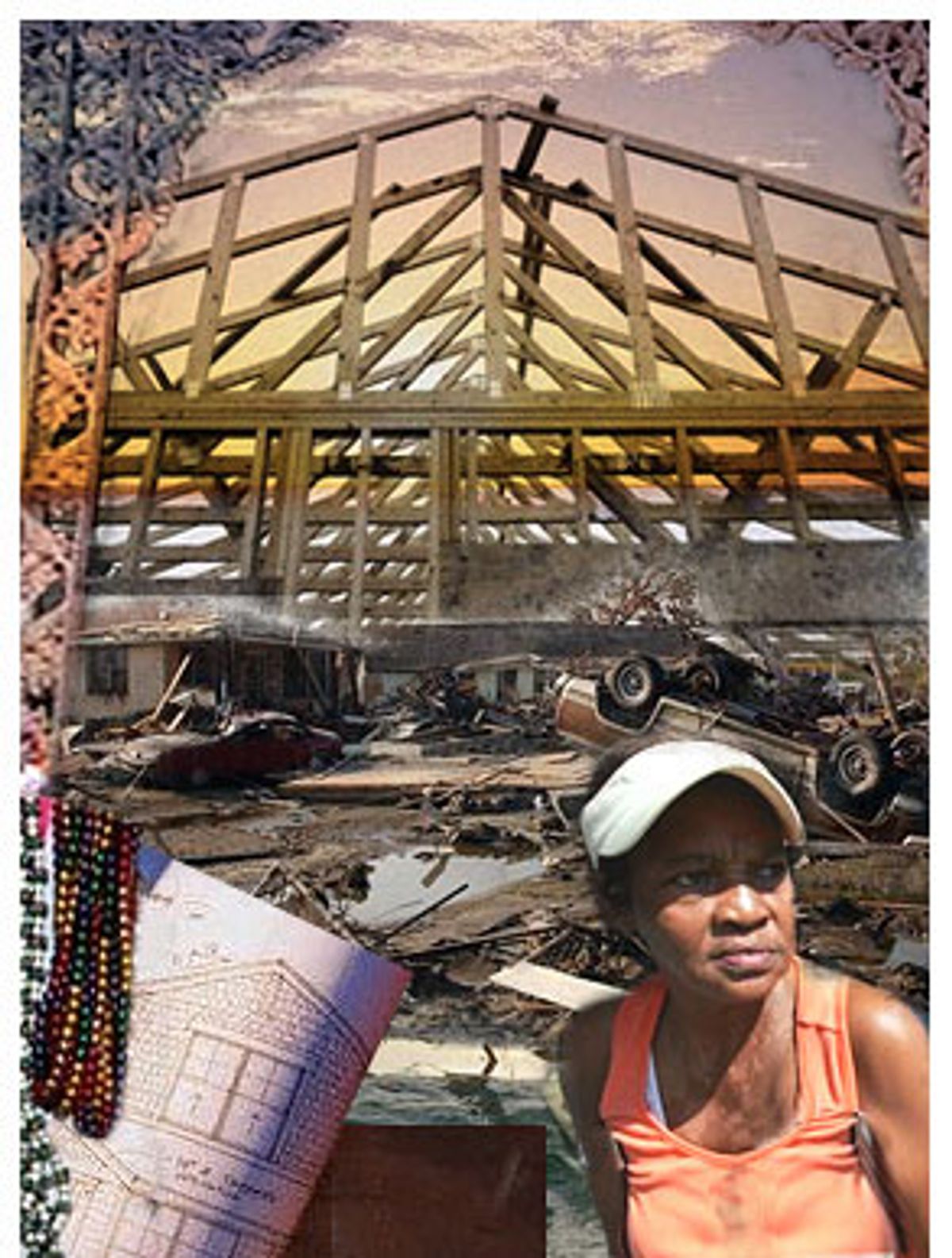

There will no doubt be a debate about whether, when and how displaced residents should return to low-income neighborhoods. Should policy emphasize bringing everyone back, or look for a way to follow the evacuees with the aid they need, and not try to attract them back, especially to neighborhoods that were devastated before the flood? Destroyed homes raise the possibility of creating entire new developments, or rebuilding the same houses in the same place. How do we balance the impulses of developers, the realities of a destroyed built environment, the theories of policymakers and the desires of residents?

Craig Colten

I feel that the destruction of hundreds of acres of houses in some of the lowest areas of the city presents a tremendous opportunity. It makes little sense to rebuild in the most vulnerable locations and to put the most vulnerable back in harm's way. New Orleans was designed to flood and will flood again. Using space that has suffered total annihilation as flood retention basins would reduce costs following future floods. With impending population loss, there may not be a need to return all that real estate to residential and commercial land uses.

In conjunction with the redistribution of land uses, steps need to be taken to help communities transplant themselves to less flood-prone zones. This may be the biggest challenge.

Any kind of redevelopment packages should include incentives or costs to avoid repeating past environmental mistakes. To discourage redevelopment of the most flood prone zones, there should be heavy "risk" fees. This might include the type of commitment imposed on those developing landfills: They have to demonstrate the financial ability to close them. But in the case of New Orleans, developers would have to demonstrate the ability to rebuild after the next flood.

The physical environment is key to successfully rebuilding New Orleans, and redevelopment plans need to begin and end with this in mind.

Angela Glover Blackwell

The evacuation preceding and after Hurricane Katrina is reminiscent of the massive American Dust Bowl migration and the post-World War II journey of many African-Americans from the rural and small-town South to northern cities. The implications of this population shift are enormous, and will undoubtedly shape the demographic and sociological future of New Orleans and the nation for decades to come. But because of the breadth and diversity of displaced Louisiana residents, there is no "one size fits all" policy solution for resettling New Orleans and the Gulf Coast.

Certainly, there are residents of all races and income levels who eagerly await the opportunity to return to their beloved Gulf Coast neighborhoods. However, some displaced residents disenchanted with the lack of opportunity offered by entrenched, concentrated poverty in New Orleans -- and perhaps, though of course not under ideal circumstances, experiencing life outside the city for the first time -- may now be inspired to settle in their temporary communities, with the hope of rebuilding a new and better life. Still others, evacuated to random cities or towns in Katrina's chaotic wake, may wish to permanently relocate to other areas of the country, where they have family or similar social ties that can ease the resettling process and serve as important networks of social and psychological support.

For those who decide to remain outside of the Gulf Region adequate and responsible relocation support must be provided. Policies should be in place to ensure that residents are not relocated multiple times; whenever possible, provide families with choices; provide counseling for those being relocated; ensure appropriate support and transition assistance; and help households avoid being exploited by predatory lenders.

With levee breaches again flooding low-lying areas of New Orleans following Hurricane Rita, planners, policymakers and residents are facing the unfortunate reality that many residents may not be able to return to some of their former neighborhoods. What were once low-income, lower-lying areas may be significantly less habitable and sustainable than higher-income, higher-ground areas. Even some higher-income areas prone to flooding may not be feasible to rebuild to their former capacity. With the very future of existing low-income neighborhoods threatened, and a broader economic range of residents potentially displaced permanently, it is even more critical that New Orleans be rebuilt so that all communities are mixed-income communities, giving low-income residents of color opportunities to settle in safe, livable neighborhoods.

New Orleans needs widely distributed affordable housing and equitable infrastructure investment; parks spread throughout the city; attractive, modern school buildings successfully serving every neighborhood; and an enhanced transit system to connect all residents to jobs, retail and education.

Howard Husock

The question of whether to encourage, and provide support for, poor New Orleans residents to return to the city is the most central that's been raised. To this point, our conversation has verged on the generic -- what, if any, low-income housing policy should we have -- rather than focusing on the specific, and special, conditions that exist in New Orleans. Before we can join the question of the nature of the replacement housing which might be built (mixed-income? single-family?), we must face the question of whether it is practical or sensible to build new housing in areas below sea level and, if we were to decide to do so, how the details of financing and management would be handled: Should public flood insurance be provided in order to attract private developers? Should the local housing authority own and operate? Are there nonprofit groups with the capacity to take on such a job?

These are key questions which must be joined even before asking the question about whether residents should be supported in their desire to return (if they do desire to return). The complexity of these questions, however, at once makes it clear that it would be far easier to provide lump sum relocation payments to residents who want to move elsewhere -- perhaps even elsewhere in metropolitan New Orleans.

But there's an empiricial question here that we might want to ask those displaced: Do you want to move back to New Orleans or would you prefer to start over somewhere else? Let's find out what the people think.

Edward Glaeser

I'll leap in on the question of encouraging the poor to return to the city, and of rebuilding the city more generally.

My basic view is that the goal here is to help the residents, not to rebuild the city, and that the sums involved in rebuilding New Orleans are so vast that this money could be far better used providing housing and education assistance, or heck, just plain cash, to the displaced residents.

A few facts:

As an aside, the port and the energy sector are quite successful and really can pay for their own reconstruction.

All of this leads me to the view that it would make far more sense to think more about rebuilding the lives of the displaced than the city itself. Vast funds can really make a difference to these people, but not if they are spent on extremely expensive infrastructure projects that are unlikely to come to fruition in the next five years.

Xavier de Souza Briggs

I want to suggest some tentative points of consensus, and a few more specific ideas on policy options.

Angela Glover Blackwell

The television coverage of Katrina's impact on New Orleans, for the first time, showed the American people the reality of black poverty in this country. The American people were shocked and embarrassed. The last time the country had a sustained glimpse into the conditions in black America was during the civil rights movement -- then, however, the cameras captured the determination of black leaders and the courage of the young civil rights workers. This time it was the face of black poverty directly. Despite some early attempts on the part of some media to turn the victims of the hurricane into lawless vandals, what the American people saw was individuals and families and community members, just like themselves, trying to do the best they could for their friends, relatives and neighbors. They saw children and the elderly suffering because of decades of neglect, not just days of neglect. For the first time they saw their fellow U.S. citizens and they were ashamed that such neglect could exist in the land of abundance.

The people of the United States responded with their dollars, but where is the vehicle to allow the American people to send their political will to Washington to demand that the country do something about persistent poverty? This is the big opportunity: to have a sustained conversation about the continuing causes of poverty, why it is still disproportionately concentrated among African-Americans, and what strategies can effectively reverse this trend and open up more opportunties for all.

This is the time to help the American people understand the unsustainability of current development patterns that promote vast investments in suburban communities while concentrating poor people in areas that are isolated from job opportunity, not well served by public transit, and defined by failing public schools and the absence of essential amenities like supermarkets.

Based on the principles of equitable development -- and enriched by this roundtable discussion -- PolicyLink has crafted Ten Points to Guide Rebuilding in the Gulf Coast Region. As the rebuilding process unfolds over time, and as we continue our research, we will expand on these guiding principles, offering examples of promising practices and concrete policy proposals to serve not only as solutions for government, business and charitable officials, but as equitable development goals for which community leaders and residents can advocate and hold their elected representatives accountable.

Shares