Scuba diving in the bath-warm waters of Bunaken Island is to be immersed in an impossibly alien world. Blue ribbon eels unfurl their fluorescent bodies into the current, decorator crabs prance across the coral heads wearing live anemones on their backs, and ornate ghost pipefish hang above soft corals like feathered seahorses. I pass a shallow cave, waking a loggerhead turtle, and watch the giant creature knife toward deeper waters with the grace of a slow-moving pelican. Below, a white-tipped shark slices through a school of snapper.

Bunaken lies off the north shore of Sulawesi in Indonesia. The small island is one of the gems in Bunaken National Marine Park, created in 1991, one of Indonesia's first marine parks. I am here with Seacology, a nonprofit group based in Berkeley, Calif., that works with islanders around the world to help preserve indigenous communities and ecosystems. In Bunaken and neighboring Manado Tua, a perfectly round island dominated by the towering cone of a dormant volcano, Seacology is funding a revolutionary practice of reviving coral reefs.

Often called the "rain forests of the sea," coral reefs are among the world's most endangered ecosystems. Currently, all of the world's reefs would cover an area only half the size of France. Once damaged, reefs demand well over a century to regrow; in many areas, they may not grow back at all. With the reefs gone, fish disappear, and the islands themselves become vulnerable to destructive waves and erosion.

The years prior to 1991 saw a lot of bad mojo at work around Bunaken and Manado Tua. For decades, fishermen bombed the reefs with dynamite, or squirted them with sodium cyanide, to net large harvests of fish that surfaced. Low tides forced local boats to anchor amid the fragile corals, and dive boats (not to mention clumsy divers) wrought havoc as well. Storms reduced already weakened corals to rubble. By the time the national park was created, big sections of the reef were already in dire shape.

In 1998, marine biologist Mark Erdmann, a senior advisor to Conservation International, along with Indonesian activist Meity Mongdong and dive master Christiane Muller, helped create a management board for the Bunaken National Park. They managed to shift control of the park away from the central government in Jakarta and put it in the hands of local villagers, fishermen and dive operators -- people with a vested interest in preserving the area's ecology.

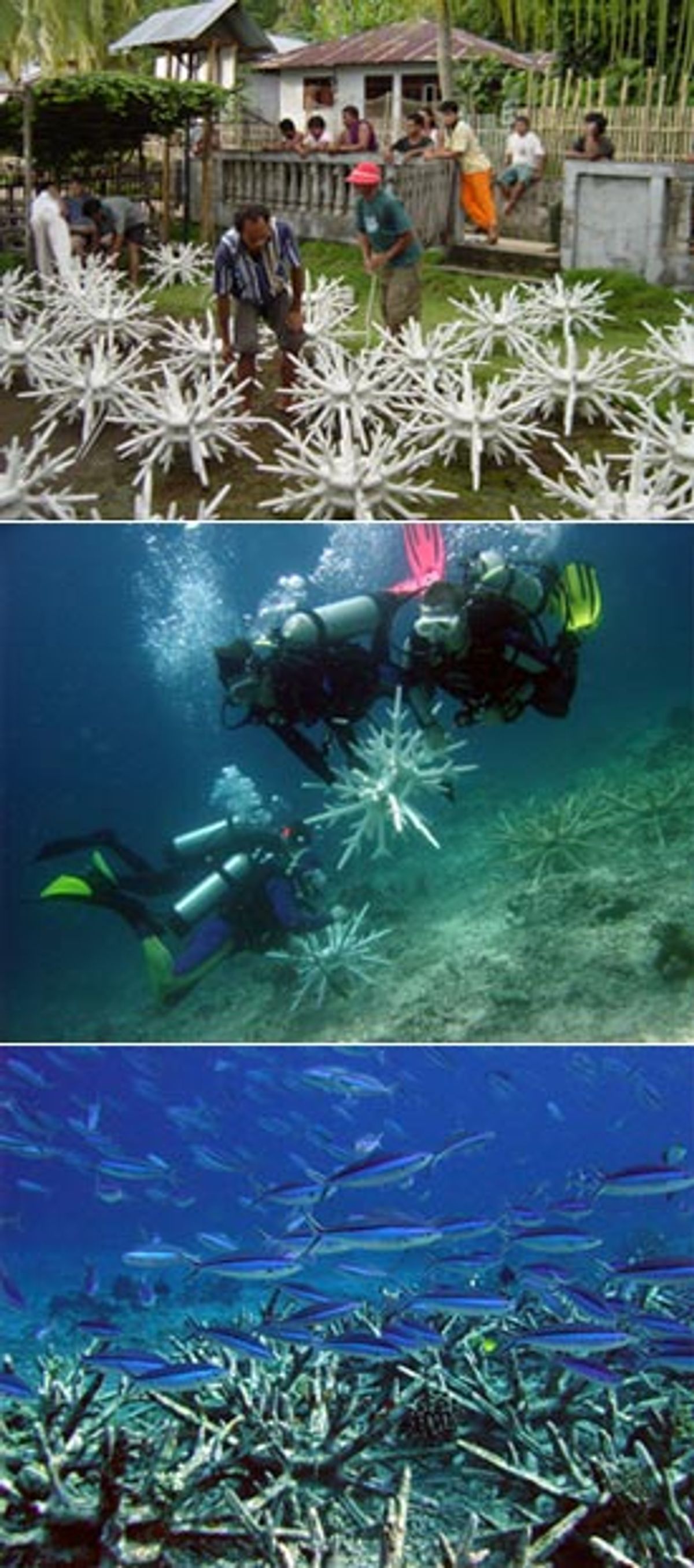

Environmentalists have employed various strategies over the years to revive crippled reefs, from sinking old railroad cars to dropping huge cement balls into the rubble; anything to give new corals a handhold. But the most elegant fix, the one funded by Seacology, may be EcoReefs: white ceramic modules, the size of squat, round coffee tables, that look like 3-D snowflakes (they're inspired by the shape of staghorn coral). Anchor enough of them in the rubble, the theory goes, and tiny polyps -- the animals that create coral reefs -- will take root on the modules' arms and fish will return in huge schools.

EcoReefs are the brainchild of Michael Moore, who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. Moore looks like a young Ed Harris and holds a Ph.D. in integrative biology from the University of California at Berkeley. "One of my favorite things about EcoReefs," he says, "is that unlike old tires or railroad cars, they're not marine pollution. They are made of harmless materials that will ultimately be broken down by wave energy -- leaving only the new reef growth in place."

In 2003, hundreds of modules were brought to the northern Sulawesi islands. Local dive operators and villagers worked together to assemble them. "It was fantastic," Erdmann says. "Everyone from little kids to grandparents helped out. Then the dive operators came to do the underwater installation."

The largest installation is off the coast of Manado Tua, where blasted reefs are shored up with 620 modules. Seacology donated the EcoReefs to the island's villagers in exchange for an agreement to leave the area alone: No Fishin'. There's no diving, either, but exceptions are made for biologists and, fortunately, journalists.

Froggies Divers sits on the curving southern shore of Bunaken's hourglass-shaped coastline, a funky resort of clapboard bungalows with thatched roofs, a sand-floored dining area and a lively, expressive population of geckos. The owner and proprietor is Christiane Muller, 67. She's as unusual a creature as you're likely to find on Sulawesi's reefs. Christiane had numerous previous lives before Froggies, working as a DNA researcher, a simultaneous translator (she speaks six languages), and as a field recorder of Southeast Asian music.

"I'd never had any interest to dive," she says, as she lights another in an endless series of clove cigarettes. "But in 1988, I was on vacation with my son, Martin, in the Carribbean. He was going scuba diving and asked me to join him. I said no, and he said, I dare you. That was all it took."

This area of northern Indonesia, where Alfred Russel Wallace got the jump on Darwin in 1859, is considered one of the most spectacular dive sites in the world. The islands are surrounded by a huge submarine trench, nearly 3 miles deep at places. Diving along the wall is dizzying; it's like hovering in space, just over the edge of the Grand Canyon. The trench is a blessing. Cool water welling up from the depths helps protect the reef against global warming and makes the area a perfect environment for everything from featherworms to spinner dolphins.

Christiane and I anchor to a mooring in sight of the village of Nigiri, where the red spires of Manado Tua's white church rise into the shimmering sky. We strap on air tanks, roll backward into the water, and begin our descent.

The EcoReefs cover several thousand square feet of sea floor. On land, they look attractive but artificial, like contemporary sculpture. Underwater, they're something else entirely: a hybrid of technology and organic life. Moore has a lot of faith in his reefs -- "If we build them, they will come," he has said -- but their growth would probably exceed his wildest dreams.

Nearly two years after the EcoReefs were submerged, their antler-shaped arms are covered with baby corals and sponges, more varieties than I can count. Parrotfish, Moorish idols and clownfish have set up shop beneath their limbs; two tiger cowries nestle near one's center.

One of the techniques used to jump-start growth on the EcoReefs is "coral transplants." Chunks of loose coral are physically attached to the EcoReefs with little plastic ties. Oddly, the modules with the transplants have done no better than the ones left to their own devices. No one knows why; perhaps corals, like delicate houseplants, favor a specific angle to the sun.

Christiane busies herself with maintenance, using a dive knife to scrape a cauliflower-like soft coral that, unchecked, will cover the modules like an invasive weed. As she works, a handsome eagle ray, about 6 feet across, hovers nearby, watching with undisguised curiosity.

An hour later, back on the boat, Christiane shakes her head. "It's incredible," she says. "There are all kinds of fish; much more diversity than when I visited last. And at least two kinds of corals: acrophora, and millephora. Millephora, fire coral, is an especially good sign, because it means big boulders -- coral heads -- will grow. The whole area will become the foundation for a new reef. This is exactly what everybody was wishing for."

We strip off our wet suits, leave the boat, and wade in toward Nigiri. Pa ("Sir") Ganche is the village chief, a big man with a broad face and fin-shaped feet. He meets us by his house, right next to the church.

"The population of Nigiri is 1,139," he says. "The EcoReefs belong to everyone and we all take care to see that no one is fishing in the no-take zone." Ganche, free-diving, checks the modules at least twice a week. "The coral grows back much faster there than anywhere else; we didn't expect it to be so quick!"

The terms of the Seacology agreement require them to wait five years before fishing here again but Ganche and the villagers are unlikely to start so soon. "For the time being," he says, "we don't plan to fish there again at all."

The next morning I meet with Pa Yunus, the local coordinator of Bunaken National Park, in Froggies' open-air dining room. With his coiffed black hair and world-weary grin, Yunus looks like an Indonesian Clark Gable, around the time of "The Misfits."

Yunus reviews the park's figures with me. About 40,000 guests visited Bunaken in 2003, each paying a modest entrance fee (for me, about $18). This generated more than a billion rupiah -- over $100,000 -- in revenue. Eighty percent of this goes to park management, which includes boat patrols of protected areas, moorings, salaries and a fund shared by the 31 villages within the park. The rest goes to Jakarta.

Yunus is mainly involved with the security patrols, which are still needed. In August, a boatload of men were caught fishing illegally in the waters off Manado Tua. "They threatened us with their spear gun," says Yunus, "but stood down when the park rangers showed their pistols."

On the Bunaken reefs, there's a species of big-lipped wrasse so colorful that one might mistake it for a parrotfish. During my final dive, I see one following me; it stays by my side nearly 20 minutes, occasionally darting off to gnaw at the corals.

When I return to Froggies and tell Christiane, she laughs with delight. "Nine or 10 years ago," she says, "there was one wrasse -- just one -- who would follow people that way. The fish had figured out that by doing so it could leave its territory without being chased by other fish. Now, all the big-lipped wrasse are doing it. How they learned this from each other, no one knows."

The encounter seems like a wonderful metaphor. Maybe all the animals in Bunaken National Marine Park will one day come to see humans as their allies.

Shares