Abbie Hoffman passionately wanted a popular film made about his life. He even playfully titled his 1981 autobiography "Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture." Two decades later, the Abbie biopic "Steal This Movie" has come and gone, a relative nonevent. While the flick will live on in cable and video, some may claim that the film's popular failure proves the prankster, lefty countercultural politics that Abbie lived by irrelevant to the present moment.

To examine the relevance, or lack thereof, of yippieness in the year 2000, I sought out one of Abbie's closest friends and yippie compatriots, Stew Albert.

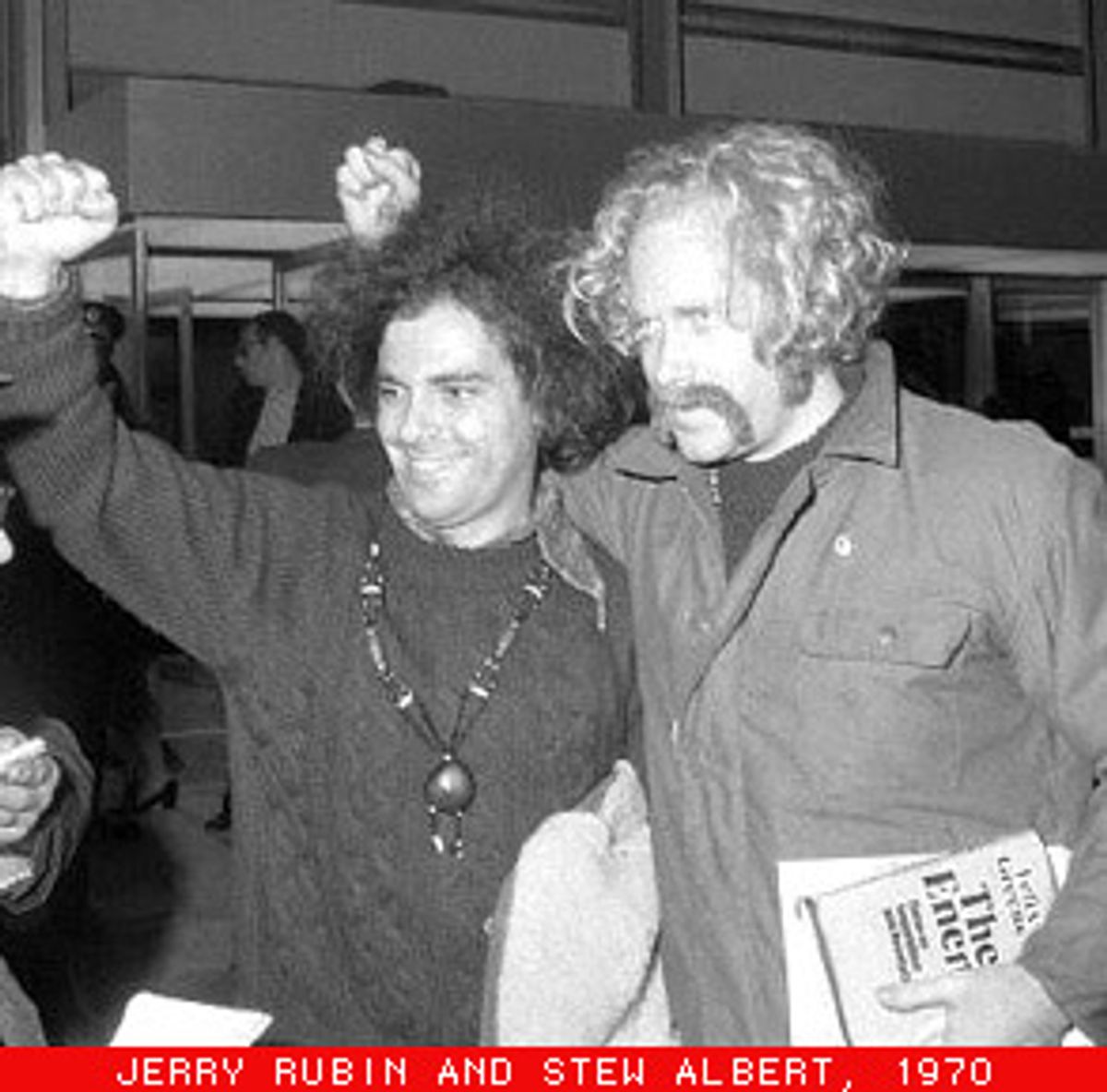

Albert was the vaguely serious one among the lunatics who made up the initial yippie front guard, a cast of characters that included widely known countercultural players such as Allen Ginsberg, Jerry Rubin, Anita Hoffman, Phil Ochs, Ed Sanders, Paul Krassner and eventually John Lennon and Yoko Ono. And he was instrumental in pushing the yippies toward the extreme leftist politics that followed the summer of 1968, negotiating a "Yippie-Panther Pact" with Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver. A slightly mellowed Albert now lives in Portland, Ore., with his wife, fellow yippie graduate Judy Gumbo, where they both remain active in leftist environmental politics.

I was one of their youthful followers. In 1968, Abbie's first book, "Revolution for the Hell of It," exploded in my adolescent brain -- more Molotov cocktail or acid tab than tome. My many months of trying to connect the Marx of my political education to the Kesey of my pleasures were at an end. None of that mattered much anymore. What mattered was how alive we young people were. We would reject the straitjacketed bourgeois workaday life, screwing, tripping and dancing our way to total revolution.

This celebratory existential politics has cast a long shadow over my life and work, to both good and ill effect. Some have even called my latest project -- a political party and presidential write-in campaign under the banner of "The Revolution" -- Hoffman-esque, but I wouldn't claim that degree of courage or originality.

Albert has courage and originality in spades, and our conversation ranged from the Hoffman biopic to technophobia to share-ins on Rodeo Drive.

"Steal This Movie" isn't particularly artful, but I can't imagine any young person not familiar with the amazing stream of political pranks and punch lines Abbie pulled off in the late '60s and early '70s finding these dramatic reenactments anything but inspiring.

I have some objections, however, to the film's honesty. Abbie's portrayed as a militant liberal. It doesn't really communicate that crazy sense of total revolution that was so palpable at that time. For instance, they show him leading a shout of "Hell no, we won't go!" after the conspiracy trial, when, in reality, he was talking "Off the pig, pick up the gun" at that time. I mean, I don't want to do David Horowitz's work for him, but on the other hand the whacked-out reality of that time might have made it a more complex and exciting movie. Then again, I suppose I could just go see "Cecil B. DeMented" again.

Well, the movie was definitely made by radicals, not liberals. They work in the Hollywood movie industry and usually have to turn out a liberal product. But with the Abbie film, they pushed their limits.

Abbie had a political evolution. When I first met him, he was something of an anarchistic "flower child" with a great talent for performance art. In "Revolution for the Hell of It," Abbie describes himself as a political goof-off and me as a Marxist-Leninist. Not true, but close. Over time, Abbie became more leftist and less flower child. The film catches some of this. As Abbie tells his lawyer, "Flower children have grown thorns."

In terms of the ultramilitant rhetoric, Abbie initially resisted the "Panther-Yippie Pact." That was something that Jerry Rubin and I cooked up with Eldridge Cleaver. At first Abbie thought the alliance would stop us from being yippies and turn us into imitation Panthers. But after he met Bobby Seale, he became much more pro-Panther.

In retrospect, what do you think of the whole ultraradical "pick up the gun" period, the Weather Underground, the Black Panthers and all that? At the time, it all seemed very romantic. That history still holds a lot of fascination, but it also seems pretty unproductive and wrong. And now the Panthers are frequently portrayed as having been thugs and gangsters.

It's true, the Panthers are widely described these days as thugs and gangsters -- mostly by white writers. But in their home base of Oakland, Calif., among black people of a certain age, the Panthers are still considered folk heroes.

I was involved with the Panthers between 1967 and '72. They certainly engaged in some bandit-style behavior, but anyone who was remotely close to them knows that the outlaw stuff was all on behalf of supporting revolutionary politics. Later on, the balance changed and it seems the Panthers became more of a criminal gang using politics as a cover.

Why did this happen? It has a lot to do with Huey Newton. There was a massive FBI campaign against him -- to drive him crazy and push him over the paranoid edge. I've seen the FBI memos. But there was also something about Huey that made him vulnerable to this assault. I remember once going to a movie with him in New York -- it was about black pimps and revolutionaries. Huey liked the film, but he objected to the fact that the pimps were shown living much more comfortably than the revolutionaries. "This will attract black people to the pimps. Revolutionaries need to live well to be respected." And he was talking about some very high living. I came away thinking that Huey was losing faith in the best part of himself -- and in the people he was trying to lead. It seems that Huey did eventually become a pimp, and he destroyed himself and his organization along the way. He had so much courage and brilliance. What a tragedy!

It's clearly impossible for any film or work of art to get across the energy of 1968-71. It seems bizarre now that as a high school student in 1969, I actually believed that there was going to be this total revolution, political, cultural -- you know, "Why should I worry about my grades?"

The essence of that time wasn't the demonstrations, riots or rock festivals. It was the day-to-day fact of hanging out with lots of "freaks." I lived near a college campus. You could go there any time, day or night, and find a tripped-out, high-energy human circus. People were getting high, circulating petitions, flirting, dancing and defacing government property. I remember a spontaneous meeting of nearly 1,000 people planning an antiwar action. People were happy to get together, in large groups, all the time, in a very intense way. You didn't have to go out to the desert over Labor Day weekend to find it.

And then, late in 1971, it just sort of stopped. The campus became morguelike. What happened?

Part of why our fantastic hot energy cooled off was a lack of standards. We thought anything wild was revolutionary -- anything crazy would make the world a better place. We celebrated excessive behavior. It was all part of positive social transformation. Drugs, guns, bombs ... and then unreal ideologies: If it didn't reflect middle-class life it was per se good.

I think back to the mid-'60s Berkeley, Calif., and the Vietnam Day Committee, which was dreamed into existence by Jerry Rubin. The VDC led enormous marches and teach-ins against the Vietnam War, and its Berkeley office became a major cultural political center. The movement was riding high and wide then -- it was delicious in its styles, personalities, tastes and morality. We were a peculiar blend of fun-loving hedonists and severe moralists. I was having the best time in my life, but the seeds of our decline were already present. I think the story of Angel makes the point.

The VDC office was inhabited by strange figures. Rubin complained that the weirdos kept sane people away. But a lot of work got done despite the circus atmosphere. Most of the odd characters were willing to lick envelopes and earn their night sleeping on the office floor. But not Angel the psychedelic ranger. He was too busy.

Drug ingestion wasn't permitted in the office, but many tripping acidheads sat on the old sofas and stared at blank walls. "What are you seeing, Angel?" I asked out of curiosity. "The seventh bardo," he responded. "I'm almost there." Angel was very handsome and surfer-muscular. Even when he passed into complete oblivion, Angel looked like a Greek statue of idealized masculinity. Or maybe he looked like a decadent model for a 1936 Nazi Olympics poster.

"What about the other six bardos?" I asked.

"They are only in your head."

Angel held the Berkeley record on acid tripping. He never came down. "I take acid first thing in the morning, every morning, until I see God's white light," he said.

Angel's father was a career Trotskyist from a working-class background, a friendly, open sort of guy who was involved in the VDC. But he never mentioned his acidic son, except in mumbled words and painful expressions. In Berkeley, the generational war could be waged on unique turf.

For some reason, Angel liked me. He once showed up at the VDC table when I was in an intense debate with an ROTC officer over the winnability and morality of the Vietnam War. Angel entered our discussion by looking deeply into the officer's unsuspecting eyes. The old soldier withered under the intense enemy assault and quickly fled. "I hypnotized him," he said. "I took over his mind. He'll join the VDC now. He's one of us."

I became concerned when Angel doubled his already unmeasurable acid dose. I was worried that he might come flying out the window. One Berkeley acidhead had already passed on to another realm, thinking he was a bird or a plane.

"A lot of pioneers get killed, man, but it's worth it."

One day Angel announced that he was going to levitate himself outside of Robbie's greasy cafeteria. An extensive debate broke out over his claim. Some thought the proposed levitation might take place; many argued that we should at least maintain an open mind.

A crowd showed up at the appointed time in front of Robbie's on Telegraph Avenue near the Berkeley campus. There was a tone of nervous expectation. Maybe Angel might float over Telegraph Avenue? He never showed up. He forgot. Angel never remembered anything. It wasn't that there were so many Angels. It was that the rest of us never realized that they needed to be helped, not turned into heroes.

Can 1960s-style energy be cultivated again? I suspect the idolatrous worship of the world market global economy, with its utter lack of democracy or compassion or humanistic culture, may chew itself up and produce its opposite, a rebellion on behalf of human nature and self-determination. It's already started. Young people are again taking frightening chances in police-infested and sadistic streets.

The great thing about the movement against corporate globalism is that it's a global movement. That's why the left suddenly has a presence again in America. Progressive politics took a terrible wrong turn when it starting thinking globally but acting locally. In a media culture, that was pretty much quitting.

But the movement also worries me some. For one thing, just as I celebrated the dissolution of boundaries as an acidhead in the '70s, I celebrated the coming dissolution of boundaries, including the waning power of nation-states as wrought by information technology, as a cyber-counterculturalist in the early '90s.

There are lots of hellish devils in the details of globalization, in the specific rules conjured up by the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization and so forth. But there's also a lot to be said for a global culture. And just to play devil's advocate, a lot of globalism's advocates sincerely think they're making a better and hipper world, filled with happy middle-class tech stock owners, listening to multiculti pop music while watching "Ally McBeal" and drinking Frappuccinos.

I used to argue with Abbie that he was too much of a media global-village freak. But I learned from him that Marshall McLuhan was right. Abbie drew from this insight and tried to work out a practical political strategy of influencing and transforming the village. His basic approach was to develop entertaining tactics that were irresistible to the media -- tactics that made for good visuals, headlines and quotes. And so we threw money at stock exchange brokers in New York, and I ran for sheriff of Alameda County in California and challenged my opponent to a duel, and on and on. All of these stunts were fun for those who engaged in them, and for most who viewed them through the media lens. And they all satirized the political/economic system. We received much greater attention than any comparable bunch of extreme radicals.

The tactics also had their shortcomings, like media dependency and addiction. After a while our imperative tended to be developing stunts rather than counterinstitutions. It didn't start out that way. Abbie started the Free Store in New York circa 1967, and I helped found the Free University in Berkeley in 1965 and People's Park, also in Berkeley, in the summer of 1969. Schools, parks and stores represented our effort at not just being against the system, but trying to lay the foundations for a much better way of life. But we eventually tended to put all our efforts into the stunts, and after a while this became predictable and repetitious. Repetition is deadly to the rebel impulse, and modern day anti-corporate globalists are already getting repetitious -- the same puppets, the same kind of disruption ... beware!

And I agree it's very important to say we're not against globalism. I'm for a popular participatory and democratic globalism -- maybe a soulfully socialistic globalism and not the top-down corporate variety.

I also worry about the rampant technophobia. The yippies used to say, "Let the machines do it" in advocating post-scarcity anarchy and an end to wage slavery. Most of today's young anarchists are saying, "Don't let the machines do it." It's pretty much their central tenet. Ted Kaczynski is even something of a hero.

Technophobia is the movement's new brain disease. How many people want to sit around in Barney Rubble's cave?

So how do you make political change in fragmented times? You mention the idea of a soulful socialism. These days, I'm just as interested in the Libertarians and civil-liberties-positive Democratic centrists as I am in the left. What was glorious about the early yippie idea was that it was refreshingly contemporary, more McLuhan than Marx. America was just beginning a transition from industrialism to the media communications era, and we needed, and still need, a liberating politics appropriate to that situation. I think we're still working on it. And ideologies and philosophies of the past -- from socialism to libertarianism and even to anarchism -- are worth sampling from, but only in the service of a truly novel mix. I think Abbie got that way back in 1967-68, and then maybe lost it.

And I'm as interested in the apolitical people as the activists. American culture is radically anti-authoritarian -- it's vulgar, sexy and wild. People don't know how to politically defend their enjoyment of hip-hop, porn, marijuana and "South Park," but they vote against Joe Lieberman and William Bennett every night with their remotes and their credit cards.

A couple of weeks back I spoke at a benefit showing [for the American Civil Liberties Union] of "Steal This Movie" in Missoula, Mont. Maybe 600 showed up for the event. Afterward I went for a drink, and a bunch of very friendly people came with me. We introduced ourselves, and lo and behold three of them were National Rifle Association [types]. They actually came to see a film about Abbie Hoffman and were in a good enough mood to stick around and have a drink or two with me afterward. It does set one to thinking.

Indeed, at a time when Arianna Huffington is the most yippie-esque figure in the political landscape, reality is truly up for grabs.

So what about the Abbie strategy updated to more sophisticated times? Abbie wanted to politicize the hippies. Let's take a much more pervasive irreverence that now infuses the entire culture and use it in a broad, anti-authoritarian movement. And if you really take on authoritarianism, you wind up taking on excesses in corporate power, as well as the state. In fact, people are already more concerned with privacy issues related to big business than they are with civil liberties.

How do you organize people when they are so fragmented in their causes and desires? What are the common values that bring people out into the streets -- face to face with meaner-than-ever cops? Underneath all the differences, I think, they are all seeking a new community -- a community of support, protest and rebellion. We need to start having common events that celebrate these values. In 1969, People's Park was fantastic because it demonstrated and celebrated the value of community labor in a common cause: hundreds of people, hippies to fraternity boys, working together to create a park for the people. We need events like that today -- where everybody can grab a shovel and dig in. What would be the People's Park of today?

We all hate greed. Let's have a large communal event that celebrates the value of sharing -- a "share-in," maybe a massive free flea market -- and get some famous rich people to give something of theirs away. And everyone rich and poor will be giving stuff away, and getting things they need. Do it big! Maybe in a place famous for greed, like Rodeo Drive. And get worldwide media attention.

One place where that spirit of "free" sharing still has a foothold is on the Net. The open-source movement behind Linux, and the whole Napster -- and more consciously, Gnutella -- technology, form a kind of virtual community based on sharing, and there are deep countercultural roots particularly within the Linux community.

The post-scarcity anarchism that inspired the early yippie idea was premature. It's now implicit and imminent in the economics of the Information Age and, ultimately, in biotechnology and nanotechnology. When you start dealing with self-replicating production systems, the laws of supply and demand are essentially made obsolete. It's been said repeatedly, but the basic law of information bears repeating, since its relevance only increases over time: If I give you a physical object, I no longer have it. But if I give you a piece of information, I still have it. And you can pass it around on through infinity, and I will still have that piece of information.

Now that the globe is networked and media digitized, I can post a piece of media, and in an instant everybody has access to it. With nanotechnology, it will likely become possible that I could share the codes that will self-build a physical piece of wealth, just as we now share information and media. So nanotechnology takes the economics of information into the world of real physical wealth, maybe in our lifetime.

We can argue about how to protect and inspire artists, inventors and investors in the present. But the thing that nobody is dealing with is how the whole Napster situation might be modeling a post-scarcity economy for a near future where getting paid simply doesn't matter that much -- a gift economy. Abbie would have loved that.

Shares