The "Cedar Revolution" ran into the complex realities of Lebanese politics Sunday. Hezbollah, the country's only armed militia and one of its most potent political forces, broke a lengthy silence and declared its full support for Syria. The group's leader, Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah, called for Lebanese to "express their gratitude" to Syria by attending a demonstration Tuesday against U.N. Resolution 1559, which calls for Syria to withdraw from Lebanon and for Hezbollah to disarm. While expressing support for the Lebanese opposition's goals, and framing the demonstrations not as pro-Syrian but pro-Lebanese, he accused the opposition of serving American and Israeli interests by tacitly accepting the resolution.

Nasrallah reaffirmed that Hezbollah would not disarm, saying that "Lebanon needs the resistance to defend it." The Shiite-dominated group, which drove the Israeli army out of Lebanon after a 15-year guerrilla war, has been locked in a low-intensity battle with Israel along Lebanon's southern border.

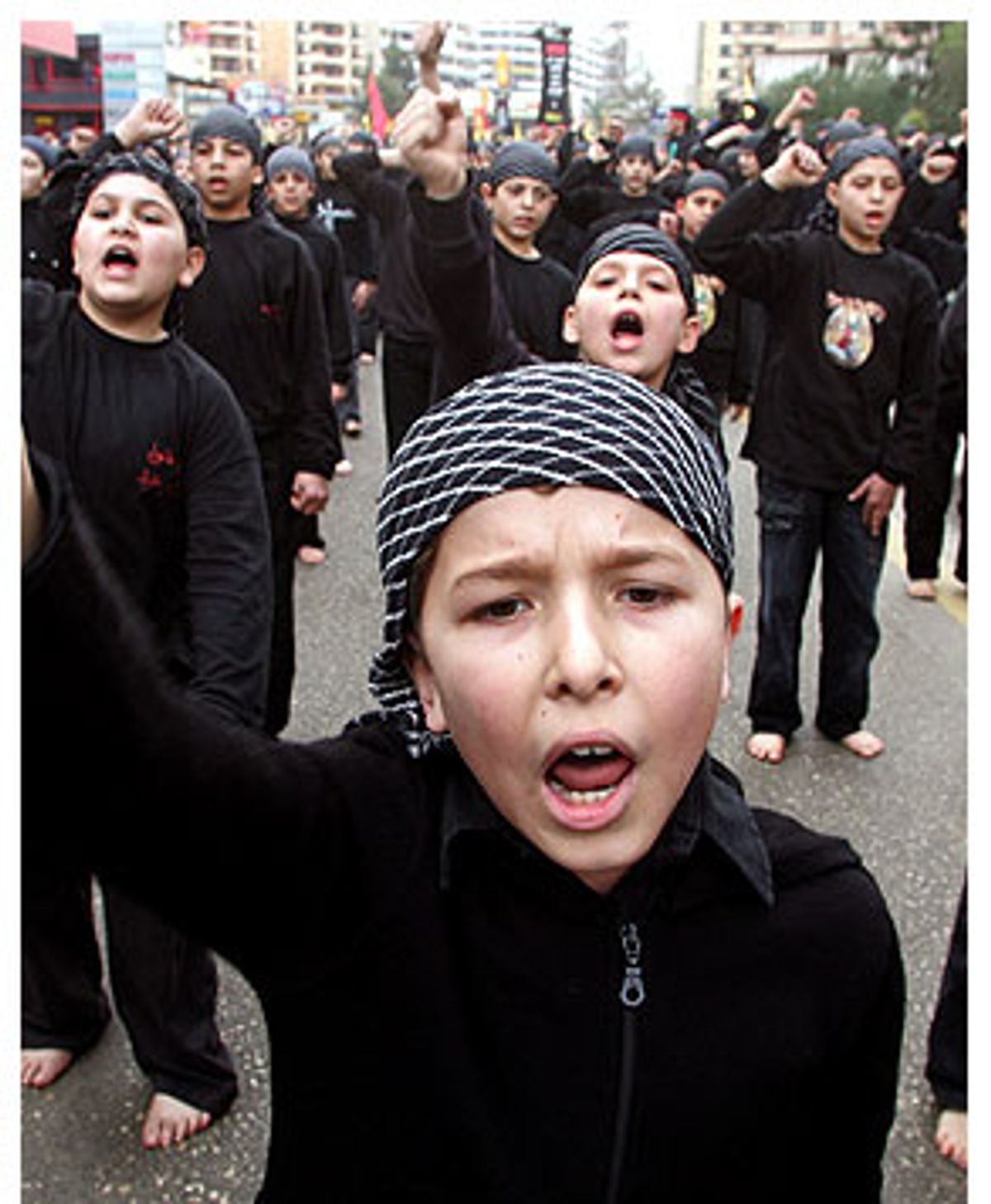

Nasrallah's intervention revealed the deep political fault lines in Lebanon, which were responsible for the nation's bloody civil war but were covered up by the mass protests against Syria that followed the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. Although those protests represented a sea-change in Lebanese politics because they united the previously fractious Sunni, Druze and Christian communities, the Shiites -- who make up 40 percent of the country -- were largely absent. Now they have spoken, and they cannot be ignored.

"Many [opposition leaders] are following U.S. demands," Nasrallah said in a meeting with reporters at his headquarters in southern Beirut. "But I ask them to take a minute and contemplate that the U.S. demands are a photocopy of Israeli demands."

Nasrallah is a famously shrewd political operator, and Hezbollah is a potent force not just militarily but politically and socially. It holds 13 seats in Lebanon's Parliament, and delivers social services for tens of thousands of mostly-impoverished Shiites. By casting the opposition's anti-Syria position as opening the door to Israeli and U.S. interference, while not opposing Syria's announced withdrawal, he played a potent card in a country where any hint of accomodation with Israel evokes bitter memories of the civil war and Israel's 1982 invasion.

A massive turnout by Hezbollah supporters Tuesday would be a pointed warning to the opposition not to go too far too fast.

The euphoric comparisons by some Western commentators of the "Cedar Revolution" to the Ukrainian "Orange Revolution" were exaggerated and reflected wishful thinking more than historical knowledge of Lebanon. Although many Shiites in Beirut have joined the opposition, it remains a movement fueled by two Christian movements that have opposed Syria's presence since 1990, by a Druze warlord once favored by Syria, and by the Sunni supporters of Hariri, who represent the rich and powerful business establishment.

One face of the opposition is displayed at Lila Brown's, a dark Beirut nightclub in the elegant, mostly-Christian Achrafiyeh district. On '80s night, the string of cheesy top-40 hits comes to a halt and the strains of the Lebanese national anthem begin. Immediately the crowd of well-heeled Lebanese patrons raise their glasses and begin to drunkenly sing, "We are all for the country, all for the glory, all for the flag."

Stuffed into a corner of Monot Street, the famous strip of bars and clubs that fill several blocks less than a half mile from slain former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri's grave and the scene of the "Cedar Revolution," the club reflects the face the world has seen of Lebanon this week: unified in a common goal that has the Syrian-dominated government on the ropes.

But even on a quick trip to the southern Beirut suburb of Ouzai, a squalid neighborhood that feels as distant from Achrafiyeh as Baghdad's Sadr City, there is a far different feeling. The Lebanese flags and signs that say "Independence 05" are not flying as in the rest of Beirut, and while a few portraits of Hariri can be seen, far more posters show the bearded and turbaned image of the late Iranian leader Ayatollah Ali Khomeini.

Other posters celebrate the struggle, not against Syrian oppression, but against Israel. They bear the faces of "martyrs" killed in the struggle against the "Zionist entity" as its enemies here call it, unable to even say the name of the nation they started fighting after Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982, and with which they remain in a low-intensity conflict to this day over the tiny, disputed Shebaa Farms region. (Israel has sent signals that it may soon withdraw from the Shebaa Farms, which would be a shrewd move because it would end Hezbollah's ostensible reason for retaining a military capacity.)

Hezbollah, or "the Party of God," formed in the wake of that invasion as a more radical and militant offshoot of the mainstream Shiite party AMAL. A highly disciplined resistance group, Hezbollah, or some of its supporters who were controlled directly by Iran, used terrorism in support of its political goals. It was responsible for destroying the U.S. embassy, kidnapping dozens of Westerners (including AP bureau chief Terry Anderson and the CIA's station chief, who was tortured to death) and car-bombing the U.S. Marine barracks at the Beirut airport, which killed more than 240 Americans and forced U.S. troops out of the country.

In order to understand the role both Hezbollah and Syria play in Lebanon, and the centrality of Israel to Lebanese politics, it is essential to have some knowledge of the Lebanese civil war and the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. The civil war in Lebanon broke out in 1975, pitting the Maronite Christians, who were afraid of losing their traditional powers, against the Palestinians, the Sunni Muslims, and the Druze, a nonorthodox Muslim sect. In danger of being defeated, the Christians appealed to Syria for help. Although it would seem illogical that the hardline, anti-Israeli Syrians would support the largely pro-Israeli Christians, the prospect of a Palestinian victory was anathema to Syrian dictator Hafez al-Assad, who feared that Palestinian attacks on Israel would lead to Syria's being drawn into a war with Israel. Syria also viewed Lebanon as part of its historic territory (in 1920 the French carved Lebanon off from various Ottoman Empire provinces that had made up what are now Syria and Lebanon). Accordingly, with U.S. and Israeli consent, Syria sent 40,000 troops across the border to prop up the Maronites and preserve a balance of power. In 1989, again with American consent, the Syrians defeated and exiled a renegade Christian general, Michel Aoun, ending the civil war.

Since then Syrian forces have remained, although the 1989 Taif Accord between the two nations called for their phased withdrawal from Lebanon. Syria has continued to treat Lebanon as a quasi-protectorate. There are currently 14,000 Syrian troops in Lebanon, as well as a pervasive intelligence network.

The Israeli invasion of 1982, masterminded by then-Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, was intended to eliminate the PLO in Lebanon. "Operation Peace in Galilee" succeeded in driving the PLO fighters out and into exile in Tunis, but it killed thousands of Lebanese and made bitter enemies of the Shiites, who had -- because of their resentment of the Palestinians, who had formed a virtual state within a state -- originally welcomed the Israelis. Israel formed a de facto alliance with the Lebanese Phalange, a Christian militia, and welcomed the post-invasion election of the pro-Israel Christian Bashir Gemayel. But Gemayel was assassinated by a Syrian agent, wrecking Israel's long-term political plan. Israeli troops and Israel's proxy Lebanese army continued to occupy south Lebanon, which Israel dubbed "Free Lebanon."

Fresh from its victory in driving out the Americans -- who were ostensibly a neutral peacekeeping force but were increasingly regarded as pro-Christian and pro-Israel -- Hezbollah turned its sights on freeing this territory, waging a 15-year guerrilla war against the Israeli forces while developing a political and humanitarian wing that increased its popularity even outside the Shiite areas. By 2000, the Israelis had suffered enough casualties that it unilaterally quit Lebanon, a victory that put forth Hezbollah as the only Arab army ever to defeat the Israelis.

Through clever political maneuvering, a vast network of social services to the desperately poor Shiite south, and the indisputable professionalism of its operations against the Israelis, Hezbollah went mainstream in Lebanese politics and became widely respected, or feared, for its ability to harness the power of the southern Shiites as a political force.

For all of its power, however, Hezbollah remains heavily funded by and deeply tied to Iran and Syria, which employ it as a key proxy force in their fight against Israel. (Syria is loath to give up this strategic military asset as long as its long-standing demand that Israel return the Golan Heights, seized in the 1967 war, has not been resolved.) The international community does not agree on how to deal with Hezbollah. The United States regards it as a terrorist organization and has demanded that Europe place Hezbollah on the list of terrorist groups, but European nations have resisted doing this, arguing that it is a political player that should be brought into the process. France, with its longstanding historical ties to Lebanon, is walking a delicate tightrope: It joined the United States in supporting 1559, but has broken with Washington over its demand that Hezbollah be called a terrorist group.

The role of Hezbollah, its militia and the larger struggle against Israel pose a huge and complicated problem for the opposition, which has yet to display a coherent policy toward the group and the questions that will have to be answered.

"Look, the opposition after Hariri's death did one thing no one could do before: It reframed the debate," according to one political activist, a nonreligious Shiite, who like most people in Lebanon will not talk about Hezbollah on the record. "Before, the argument was that it was either you were for Syria in Lebanon or you were with the Jews. That is over now and it's why you see the successes," he adds.

No high-level Hezbollah officials would grant interviews for this story, but opposition leaders recognize that without Hezbollah's cooperation there are limits to what it can accomplish. And a flat-out conflict with the group could turn deadly -- either figuratively or literally -- for much of the opposition.

Opposition leaders responded carefully to Nasrallah's statements, praising him for calling for peaceful demonstrations.

Abdul, a 23-year-old former Hezbollah gunman, has given up dreams of martyrdom for a gig as a bar bouncer and boxer-bodybuilder. He says his former comrades, with whom he remains close, are stunned and torn over the "Cedar Revolution."

"No Shiite wants to fight the Lebanese people, and they are happy to see Lebanon unified," he says. "But the fight against the Jews, to the people in the south, it has been their life for 20 years. And Hezbollah is their world."

The opposition recognizes this, but also finds itself in disagreement about how to handle the Israel/Hezbollah situation as Syria begins to withdraw. The key point of tension concerns the difference between U.N. Resolution 1559, which calls for Hezbollah's disarmament, and the Taif Accords, which do not. Syria's gradual withdrawal is in keeping with Taif, not 1559. "We are in talks with them and hope to know something next week," says one top official in the Free Patriotic Movement. The FPM is a mostly Christian opposition group whose leader, Gen. Michel Aoun, the former prime minister and commander of the Lebanese army, remains in exile in France. "We, as the FPM, want peace with Israel and will not accept anything other than full implementation of 1559, which means disarming Hezbollah. But we recognize how difficult this is and know we cannot force a conflict with them on this issue."

The Muslim and Druze groups are even less inclined to challenge Hezbollah. Walid Jumblatt, the Druze warlord and a key figure in the opposition since Hariri's death, has flat-out rejected a peace deal with Israel under present conditions, and his history of leading fighters against their troops in the Chouf Mountains outside Beirut shows his stance is probably not just rhetoric.

Hariri's people -- his sons and wife are known to be funding much of the opposition's efforts -- come from the Sunni upper class of Lebanon. They are now aligned with the Christian groups they fought during Lebanon's bloody civil war, a war whose scars are still visible in Beirut.

Getting the Sunni of Lebanon to accept a peace deal with Israel, while the Palestinian and Syrian tracks remain unresolved, is a nonstarter. And despite the religious rift between Sunni and Shiite Islam, and the social and political gap between them in Lebanon, Sunnis hold Hezbollah in high esteem for liberating south Lebanon and defeating the Israelis.

Adding to the uncertainty is the failure of Emile Lahoud -- current president and perceived Syrian toady -- to replace the government that resigned this week. It was thought he might put together a bland technocratic government to hold the country until the elections scheduled for this spring. But as of Friday there has been no announcement, so the opposition doesn't know what the next step should be.

The local papers call this an intentional maneuver by the government as its remaining members cling to power. "Internal political developments are following the rhythm of foreign contacts, and this has been translated in the delay in announcing a schedule for the special parliamentary consultations to form a new government," said the As-Safir newspaper.

"The state procrastinates and no consultations before Monday," read the headline of the top-selling An-Nahar newspaper, which said, "There are no positive indications at the horizons so far." "It seems that [the authorities] want to exploit the fall of the government -- under pressure from the opposition -- by causing an open-ended government crisis and holding the opposition responsible for the consequences." (These translations of local newspapers were taken from wire reports.)

And there remains a dispute over whether Lahoud himself and the heads of the security services should be pressured to resign, or whether street protests should be held off until the elections.

"We want Lahoud to stay -- we hate him as a Syrian-backed parasite -- but we'd rather finish the job through the elections. If he resigned, the current Parliament remains loyal to Syria and might replace him with someone else for a six-year term. So we want to wait," a FPM student organizer told me over drinks a few days ago.

But even as that appears to be the opposition position, Jumblatt has called for the entire government to be removed immediately, and small crowds -- a presence remains by Hariri's grave to keep momentum going -- often chants "You're next, you're next" whenever Lahoud is seen on the giant television screens set up for the protests.

In an ambiguous speech to parliament on Saturday, Syrian President Bashir Assad, who has been under enormous international pressure to withdraw, promised to withdraw Syrian troops to the eastern Bekaa Valley and then across the Syrian border, as called for in the Taif Accords. But his speech contained hints that left open the possibility that Syria's role in one form or other might continue. "We should not remain in Lebanon one day after there is a Lebanese consensus over our presence," Assad said. A massive Hezbollah turnout Tuesday would reveal that there is no such consensus.

"Both [the opposition and Hezbollah] are warily eying each other," one local newspaper editor explains. "The opposition has the power of many Lebanese and the international community, even today we see Egypt, Saudi, the U.N., the U.S., France, all backing the opposition. So Hezbollah is scared. It knows it will probably lose its Syrian support. I think we all know their troops and [intelligence services] will be forced to leave or will have such diminished strength that they cannot support Hezbollah anymore." But the opposition has no clear policy on this issue either. The FPM and the Lebanese Forces (an opposition group that promotes a very militant Christian stance) want to see Hezbollah weakened or destroyed, but they know their strength cannot compare with Hezbollah's.

"It's intriguing and very dangerous," he sighs. "Thank God the Israelis have had the good sense not to provoke anything here."

Shares