On a hot summer morning in 2004, Garett Reppenhagen dragged himself out of his cot at a rudimentary Army base, 40 miles north of Baghdad, for a briefing on the day's combat mission. His battalion of the 1st Infantry Division was holed up in an abandoned warehouse and sleeping in steel trailers with sandbags stacked in the windows. They were stationed on the outskirts of Baquba, a city rife with insurgents in the violent Sunni Triangle. As the soldiers gathered around their Humvees, Reppenhagen, a scout and sniper, figured he knew what his lieutenant was going to say.

There had probably been another roadside bomb nearby. That meant Reppenhagen and his platoon, acting on intelligence that might be good or bad, would drive their Humvees into a nearby neighborhood, seal off entire town blocks, search houses and round up a bunch of men who might or might not have some tie to the insurgency.

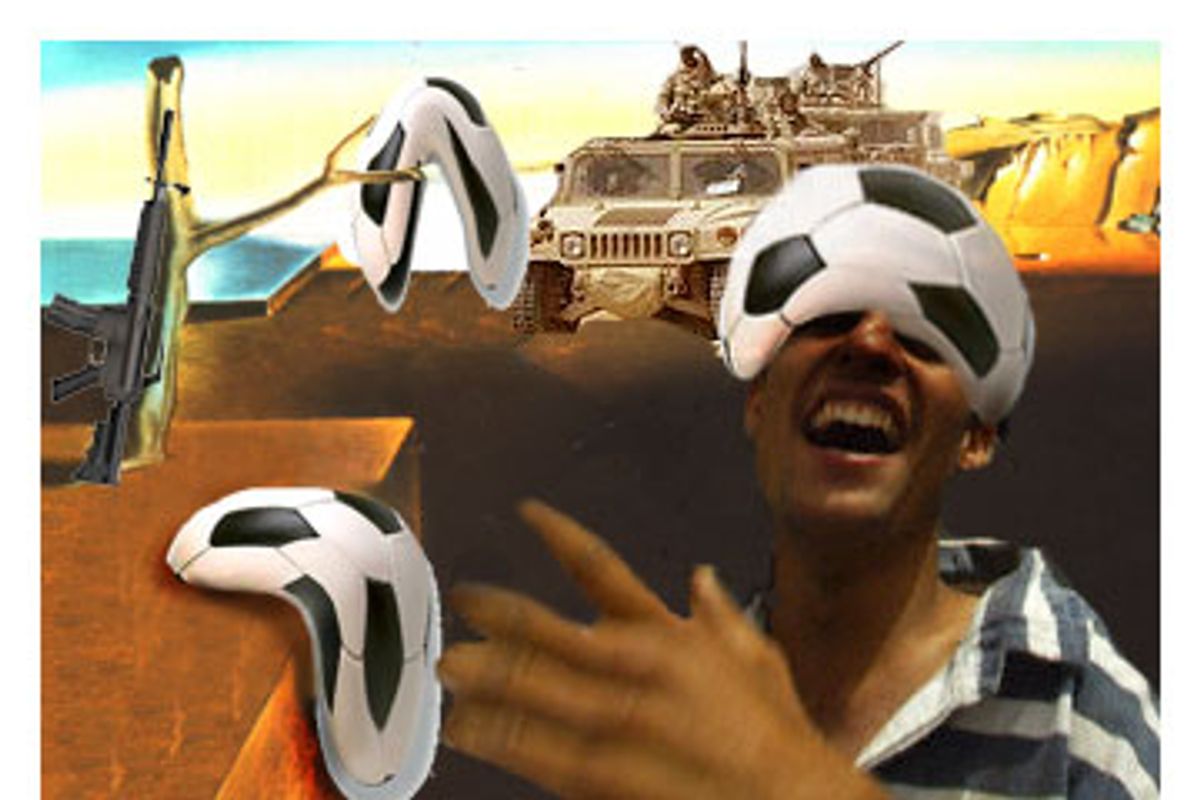

What the lieutenant told them, however, had nothing to do with the enemy. They were going to hand out soccer balls to Iraqi kids in the surrounding villages. Reppenhagen was surprised. "You do so much crappy shit over there that when you get a mission to actually help people, it's encouraging," he said.

Reppenhagen, now 31, has certainly seen his share of crappy missions. During his 2004 duty in the Sunni Triangle, he was sent on countless raids. On nighttime patrols, when a muzzle flash appeared from a darkened building, he and his platoon would respond with the full force of .50-caliber machine guns mounted atop Humvees until the ammunition was spent -- even if that meant leveling a nearby building. If an insurgent was thought to be hiding in a house, they'd call in a tank to blow it up rather than do a risky search on foot.

As a member of a six-man sniper team, Reppenhagen was ordered to track down and kill insurgents in extremely dangerous areas. At other times, he and his battalion would cordon off streets, kick in doors on squat cement houses, and detain men 18 and over for minor offenses like being in a house other than their own or failing to show proper ID. "Half of the time, we got the wrong damn house," Reppenhagen said. At least handing out soccer balls, he thought, was one thing the Army could do right.

At Forward Operating Base Scunion, the camp's official name, the lieutenant told Reppenhagen and company to pick up the load of balls from Forward Operating Base Warhorse, which was close by. They would then drive around the towns of Al-Hadid, Hib Hib and Kahlis and hand them out to the kids who often ran beside the Army Humvees and called out for candy, water or money.

Of course, there was an ulterior motive to the kindly gesture, as it behooved the Army to earn the sympathies of local Iraqis, who could aid them in the search for insurgents. The operation could be seen, in the parlance of the Army counterinsurgency manual, as maintaining "moral legitimacy" with the Iraqis.

After all, nothing is more popular in Iraq than soccer. "There are soccer fields everywhere," Reppenhagen said. "Mostly it is just dirt lots. They don't have goal posts and so use stumps. Sometimes the kids play in the street. I swear, all they do all day long is play soccer."

It wasn't clear who came up with the idea to win over Iraqis with soccer balls. A March 2004 press report from the Pentagon describes a unit of the 1st Armored Division handing out soccer balls in the Karadah district of Baghdad. "The children were thrilled to receive new soccer balls as soldiers tossed the balls to the boys and girls," the report said. In a December 2004 release, Kiowa helicopter pilots with the 1st Cavalry Division are described tossing soccer balls to grateful kids in an operation aptly dubbed "Operation Soccer Ball." Spc. Thom Cassidy, who worked in the logistics shop in Reppenhagen's battalion, recalled that giving out soccer balls to the kids around Baquba was passed down from higher command to a battalion colonel at the base. In any event, Cassidy said, "this was a very, very Army idea. This was the prototypical Army idea."

At Forward Operating Base Warhorse, Reppenhagen and his fellow soldiers encountered a five-ton truck stacked with large cardboard boxes. They began to unload the truck and open the boxes. There were maybe 50 soccer balls in each box. But the balls had not been inflated. They were all flat. Reppenhagen scoured the boxes. No pumps. What was worse, nobody had bothered to pack the needles to inflate the balls.

Resourceful soldiers that they were, the men carried some of the balls to mechanics in the motor pool. "They tried to pump them up with tire pumps," Reppenhagen said. But the mechanics had the equipment to inflate Humvee tires, not soccer balls.

Frustrated, the soldiers asked their commanding officers what to do. None were sure. They kept calling their own superiors. Cassidy suggested that they order pumps and needles, which would arrive in about two weeks. The battalion colonel quickly tired of the whole discussion and said he wasn't about to requisition soccer ball pumps. "He decided this was a waste of time," Cassidy said. "His thought was, 'Iraqis should be grateful.' Not, 'They will be grateful' -- 'They should be.'" Finally, the lieutenant commanded the troops to deliver the balls to the children. "He was pretty much like, 'Shut up and hand out these soccer balls,'" Reppenhagen said.

It seemed crazy. "We were so pissed," said Reppenhagen. But orders are orders. When you are told to hand out flat soccer balls, you hand out flat soccer balls. So the soldiers who served in 2nd Battalion, 63rd Armored Regiment piled the flat soccer balls into their Humvees. Driving through the Sunni Triangle's war-torn towns, they tossed the deflated balls to children, who crowded the sides of the roads, running beside the canals and lush greenery that lined the banks of the Diyala River. "Kids were swarming us," Reppenhagen said. "We went to a couple of schools and delivered stacks of them. Everybody we saw got a flat soccer ball."

Which, of course, the kids quickly figured out. Pretty soon, Reppenhagen recalled, "They were like, 'What are you doing? What are we supposed to do with this?" When the Humvees began to retrace their route back to the base, the futility of the operation was becoming painfully clear. "Kids were wearing these soccer balls as hats," Reppenhagen said. "They were kicking them around. They were in trees. They were floating in canals. They were everywhere. There were so many soccer balls."

Today, Reppenhagen still cringes when he recalls the soccer ball operation, which to him says so much about the entire U.S. occupation in Iraq. He recently left his job at Veterans for America, a veterans' advocacy group, and currently serves on the board of Iraq Veterans Against the War. A spokesman for the 1st Infantry Division, Lt. Col. Christian T. Kubik, said Reppenhagen's battalion commander does not recall the soccer ball operation. In an e-mail, he took issue with the characterization of soldiers blindly following orders when they handed out the deflated balls.

"America is filled with veterans who know that this comic view of soldiers dumbly following orders is completely without basis and almost laughable in its propagation of stereotype," Kubik wrote. "Soldiers are Americans, not automatons." He added: "To focus on the air in the balls, or lack thereof, undermines the American spirit of generosity and completely misses the point of giving."

Reppenhagen said he certainly knows what he and his platoon got when they drove to the base: The Iraqi kids were expressing their hearts and minds with rocks and stones. "On the way back, kids were throwing rocks at us," he said. "I assumed it was because we gave them deflated soccer balls. Maybe if we had given them inflated soccer balls, they would have been out playing soccer."

Shares