Kevin Ryan doesn't want to talk about his recent fling with Web stardom. He's a bit rueful and more than a little nervous about it, in fact, and wishes the whole thing would just go away.

If you missed his star turn, here's what happened: Ryan, a 33-year-old Houston music producer and author, went into his home studio and engineered a sort of retro mash-up of two of his favorite artists, Bob Dylan and Dr. Seuss.

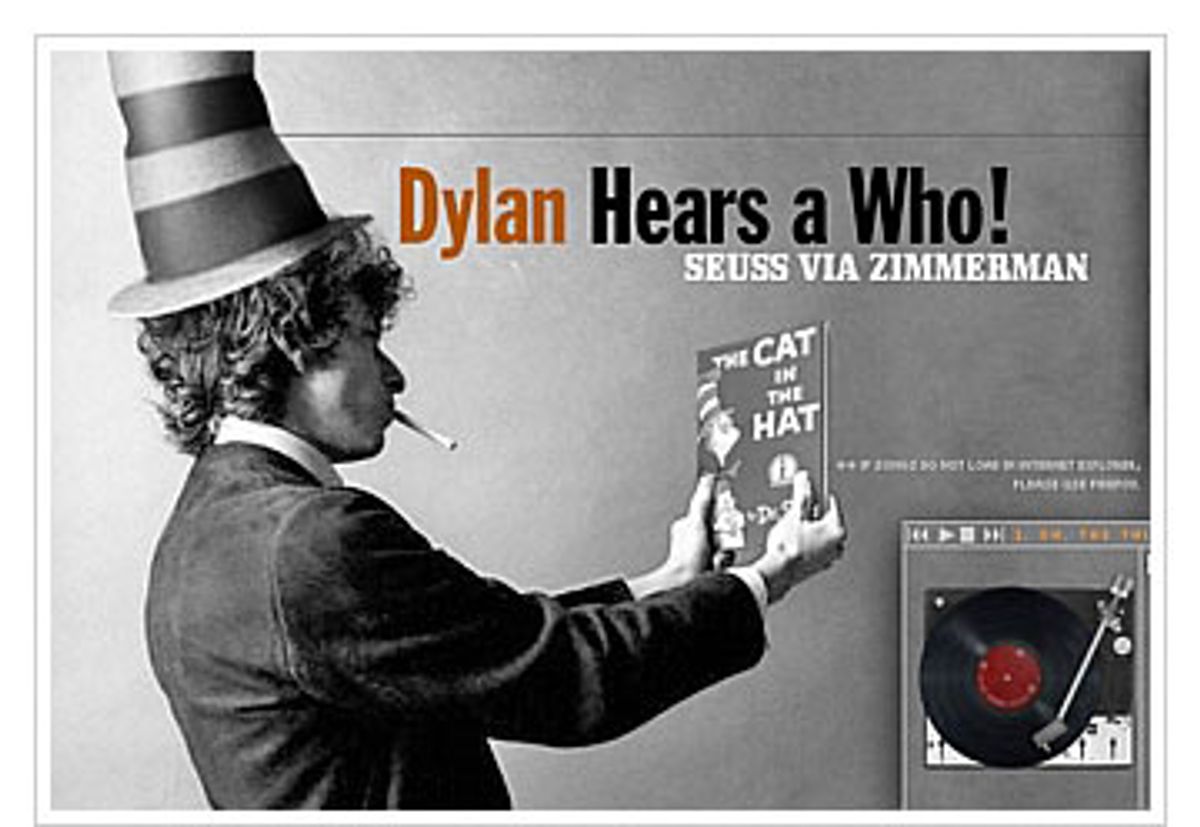

Ryan took the text from seven Seuss classics, including "The Cat in the Hat" and "Green Eggs and Ham," and set them to original tunes that sounded like they were right off Dylan's mid-'60s releases. He played all the instruments and sang all the songs in Dylan's breathy, nasal twang. He registered a domain name, dylanhearsawho.com, and in February posted his seven tracks online, accompanied by suitably Photoshopped album artwork, under the title "Dylan Hears a Who."

"Green Eggs and Ham" was set to a tune and arrangement somewhere between "Highway 61 Revisited" and "Subterranean Homesick Blues," complete with Dylan's rushed, occasionally sneering phrasing. Familiar passages are run together in impatient run-ons:

Would you eat them in a box?

Would you eat them with a fox?

Not in a box not with a fox

Not in a house not with a mouse

I would not eat them here or there

I would not eat them anywhere

All this accompanied by an up-tempo electric band, complete with the jaunty skirling of a Hammond organ.

It was clever and delightful. Ryan had immersed himself so fully in Seuss' words and Dylan's style that he managed to merge two quite different creative intelligences. Many who have heard the tracks come away convinced they're really listening to Bob Dylan.

Reached in Houston, Ryan confirmed the work was his but declined to speak about it on the record except to say he never expected it to attract any attention. Instead, "Dylan Hears a Who" was quickly picked up by bloggers and the popular Web site BoingBoing and went viral, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors.

Then Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the La Jolla, Calif., firm that publishes the works of the late Theodor Geisel, heard "Dylan Hears a Who." Only two weeks after word of the site began spreading, Ryan got a cease-and-desist demand from the Seuss lawyers, who said the site and songs infringed the company's copyrights and trademarks. Ryan complied quickly and quietly. Instead of the Dylan/Seuss tracks, visitors to dylanhearsawho.com find a brief message saying the site has been "retired" at the request of Dr. Seuss Enterprises.

If you were caught up in the momentary wonder of how someone could execute such an ingeniously perfect blending of period musical style, '60s attitude and loopy storytelling, it was tempting to see all of this as just another case of a heavy-handed corporate copyright holder -- a master of copyright war, to call on the old Dylan oeuvre -- sticking it to the little guy.

Ryan -- best known as the coauthor of "Recording the Beatles," a meticulous investigation of every track, take and song the group committed to vinyl -- was face-to-face with a company that zealously guards its intellectual property. Losing a copyright-infringement case can be extremely expensive. In addition to the federal law's $150,000 maximum in statutory damages, defendants can find themselves on the hook for the plaintiff's legal fees. (Dr. Seuss Enterprises declined comment on "Dylan Hears a Who," questioning why it was even a subject of interest. Dylan's attorney did not return a call for comment on Ryan's work.)

As it happens, if Ryan was going to get into a fight over the legal limits of parody, he couldn't have run into a better-prepared opponent than Dr. Seuss Enterprises. The company helped write an important chapter in current case law regarding what is and what isn't parody for purposes of fair use. In 1996, Dr. Seuss successfully sued Penguin Books to stop publication of "The Cat NOT in the Hat," a send-up of the O.J. Simpson murder written and illustrated in the Seuss style.

Still, the Copyright Law of the United States was put on the books by the very first Congress not to secure the intellectual property rights of the corporate few, but to "promote the progress of Science and the Useful Arts" -- even when that progress involves a writer, artist or musician lifting words, images or melodies from one source as part of making something new.

So if there was a legal defense for Ryan using Dr. Seuss' words and images -- and Dylan's name and likeness, for that matter -- it probably lay in the Copyright Law's "fair use" exception. The provision, which reaches back at least to early 18th century English law, allows "the fair use of a copyrighted work ... for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching ... scholarship, or research."

What does that mean when it comes to the unlikely trio of Dylan, Seuss and Ryan?

I asked Jennifer Rothman, an assistant professor at Washington University Law School in St. Louis who specializes in intellectual property, entertainment law and the First Amendment. Her take surprised me, coming from someone who said she's on the side of small creators vs. corporate intellectual property interests.

"There's no question that big intellectual property holders are intimidating small-time players with cease-and-desist letters and unreasonable I.P. claims and that the small players often buckle under," she said. "This does chill speech."

But the general climate aside, she said Ryan "is not standing on solid ground. If I were him, I wouldn't want to litigate this because most courts would likely find he violated current I.P. law."

Then she walked me through her reasoning, using as a primer Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, the U.S. Supreme Court's unanimous 1992 ruling that found 2 Live Crew's smutty, suggestive and sophomoric take-off on Roy Orbison's "Oh, Pretty Woman" deserved fair-use protection as parody.

The key to the court's finding was that Luther Campbell, the author of the 2 Live Crew work, did more than grab snippets of the original lyrics and sample portions of the song's instrumental track. In the language of fair use, Campbell's version was a "transformative" new work.

"While we might not assign a high rank to the parodic element here, we think it fair to say that 2 Live Crew's song reasonably could be perceived as commenting on the original or criticizing it, to some degree," Associate Justice David Souter wrote for the court. "2 Live Crew juxtaposes the romantic musings of a man whose fantasy comes true, with degrading taunts, a bawdy demand for sex, and a sigh of relief from paternal responsibility. The later words can be taken as a comment on the naivete of the original of an earlier day, as a rejection of its sentiment that ignores the ugliness of street life and the debasement that it signifies."

However, whether a work is "transformative" in going beyond an original with "new expression, meaning, or message," is just one of the factors courts must consider when assessing fair use. Judges must also weigh whether a new work is created for profit; whether the original work merits protection from copying; how much of the original was appropriated to make a new work; and what market impact the appropriation might have on the original work.

In Rothman's opinion, Ryan's work flunks two essential tests.

First, it fails to be a transformative work in that there's no clear comment on or criticism of the Seuss original. "I think he's not even close to the line on this. He's far in the infringing camp," Rothman said.

Second, "Dylan Hears a Who" appropriates too much of the original material. "It takes the entire Dr. Seuss material; it's not like taking just a few lines to make a point," Rothman said. "One question a court would ask is, Did the defendant take more than was necessary for a parody? and here I think the answer is clearly yes." The one factor that might weigh in Ryan's favor, Rothman said, is that "Dylan Hears a Who" did not appear to be commercial.

I asked Rothman to back up for a moment and consider an argument that went like this: By inserting Dr. Seuss' words into a novel context, specifically, the voice and style of a radical 1960s troubadour, the "Dylan Hears a Who" project comments on the original work by exposing a sly, rebellious, countercultural dimension to his work that has remained hidden. At the same time, it exposes a playful though pointed creative intelligence shared by two of the most important figures of the 1960s.

Rothman said that wasn't a bad stab at a defense, but didn't think a court would buy it. "It's too obvious that the point of the site is, Wouldn't it be fun to sing Dr. Seuss in a Dylan voice? And that's not something most courts would be sympathetic to."

Ryan himself -- speaking, of course, after he heard from Seuss' lawyers -- seems to confirm Rothman's judgment when he wrote in an online forum that "Dylan Hears a Who" was merely "a fun little project." Having fun doesn't make it impossible to produce parody, but to have a ghost of a chance of prevailing in a fair-use dispute, you need some serious justification and the ability to demonstrate it. In a sense, Ryan undid his most serious defense by admitting he used someone else's protected material just for fun.

Ryan's work aside, Rothman said the current copyright regime is an increasing burden to artists and one that, the three-century history of fair use notwithstanding, is drawing an ever tighter circle around the choices of writers, musicians, filmmakers and creators of all stripes.

A case in point is an often-cited incident involving filmmaker Jon Else and his 1999 documentary "Sing Faster: The Stagehands' Ring Cycle." As detailed in "Free Culture," by Stanford University law professor Lawrence Lessig, Else shot a scene of stagehands playing checkers. In the background, "The Simpsons" was on TV. Else wanted to use a four-and-a-half-second shot that included the cartoon, which was incidental to the scene. It was probably a case of fair use, but he sought permission from the copyright owners. Fox said Else could use the 4.5 seconds at its educational rate: $10,000. Dismayed by the cost and the prospect of costly and time-consuming litigation to keep the shot intact, the filmmaker dropped his request and wound up digitally substituting a documentary he owns the rights to onto the TV in the scene.

"In theory, fair use means you need no permission," Lessig concludes. "The theory therefore supports free culture and insulates against a permission culture." But summarizing Else's experience, he says, "The fuzzy lines of the law, tied to the extraordinary liability if lines are crossed, means that the effective fair use for many types of creators is slight. The law has the right aim; practice has defeated the aim."

So is there hope for daring creators? Even those who, like Ryan, make something remarkable on a lark? Rothman points to efforts such as the Chilling Effects Clearinghouse, set up by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and law clinics at Harvard, UC-Berkeley, Stanford and several other universities to help pool information on copyright issues and advice for artists facing cease-and-desist demands.

But she also suggests that the most effective response might be fighting fire with fire: being prepared to go to court to fight unreasonable intellectual property demands from corporations. Of course, a movement like that would need deep pockets, and Rothman says some have arrived on the scene: Google, for instance, which has seen copyright law become a major factor in many of its activities.

"We're just starting to see a movement to push back," she said. "I and other I.P. scholars are saying we need more litigation of these questions."

In the meantime, "Dylan Hears a Who" lives on, even if Ryan's site is shut down. The songs were online long enough for music fans to do what fans do on the Web: copy the songs and repost them. Despite the fumings of the intellectual property grinches, Bob Dylan's gig with Dr. Seuss is guaranteed a long run.

Shares