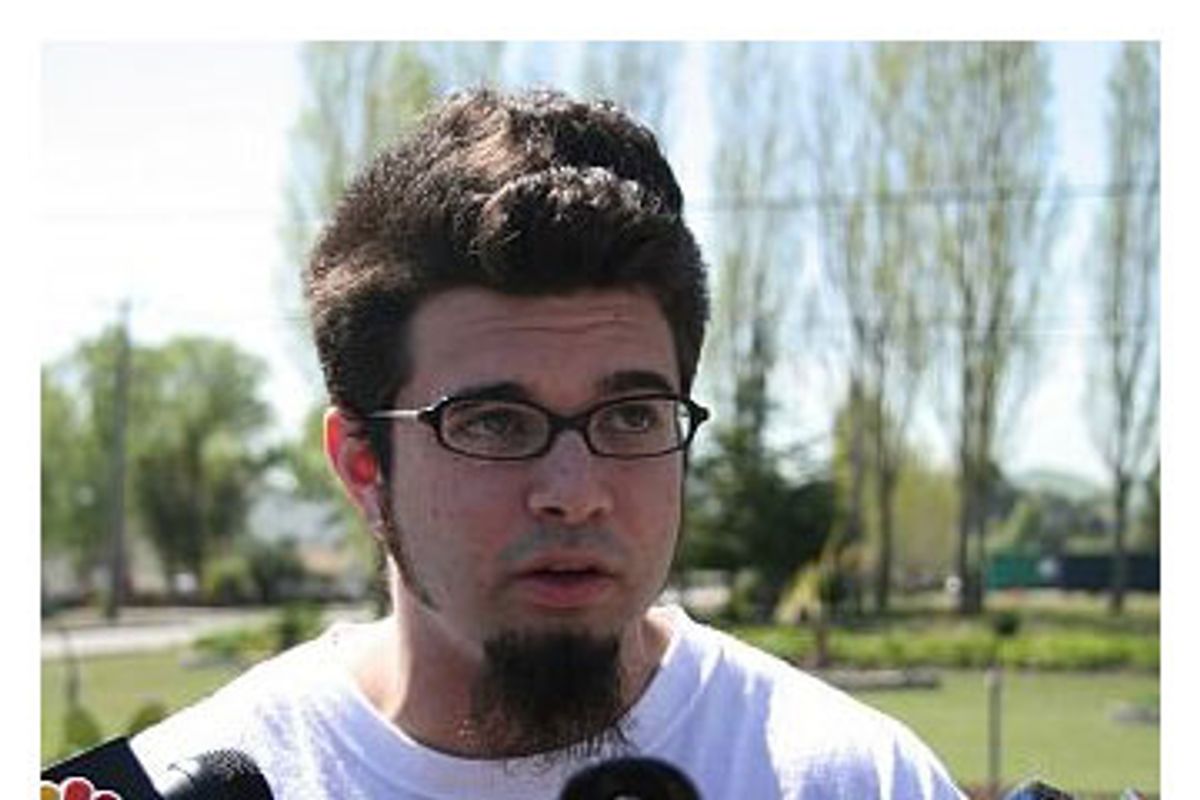

Over the past seven and a half months, 24-year-old video blogger Josh Wolf has gone from being a young political activist with a camera to one of journalism's better-known -- and most controversial -- martyrs. When he walked out of a federal prison in Dublin, Calif., on April 3, he held the American record for most time served behind bars for refusing to give up source material.

On July 8, 2005, Josh Wolf was at the scene of an anarchist demonstration in San Francisco's Mission District that turned violent. Someone fractured a police officer's skull with an unknown object, and protesters allegedly tried to set the same officer's car on fire. Wolf, who maintains a video blog called the Revolution Will Be Televised, videotaped the protest. He posted parts of his tape on the Indybay Web site, and sold part to a local TV station. A federal grand jury began looking into the riot, and in 2006, it issued a subpoena to Wolf, seeking the unreleased portions of his footage, as well as his testimony. He refused to comply with the subpoena, and on Aug. 1, 2006, was held in contempt of court. He was imprisoned until Aug. 31, when he was allowed to post bail, but was imprisoned again in mid-September of that year. He was held there until April 3 of this year, when prosecutors dropped their demand that he testify and Wolf handed over the full video.

Wolf's incarceration has led to a debate over what, exactly, a "journalist" is in the age of the Internet, and whether Wolf could credibly claim to fit the definition. Wolf's blog used to include a line on its homepage in which he described himself as many things -- "an artist, an activist, an anarchist and an archivist" -- but not a reporter or journalist. In February, San Francisco Chronicle columnist Debra Saunders called Wolf "a blogger with an agenda and a camera" and said she did not understand "why newspapers ... refer to him as the 'longest-imprisoned journalist' in America."

Salon spoke with Wolf about his time in prison, his decision not to comply with the subpoena and how he defines "journalist."

What has this whole experience been like for you?

Overwhelming. It's broken down a lot of ideas that I thought were true, and were revealed to be false. It's also reinforced suspicions I had that turned out to be true.

What do you mean by that?

I mean, well, many of those thoughts and suspicions revolve around the federal justice system and whether people are [really guaranteed] fair trials -- which they're not. Even when you have money and spend $100,000, in the federal system an attorney's nothing more than a deal-broker.

And in terms of stuff that transpired that was surprising to me, and shouldn't have been -- when you think of felons, you think of them as all being these rough-and-tough and unkind people. In reality, they're just people that were put in a desperate situation and acted out in a desperate manner to achieve the means that they felt were necessary at that point in time.

What was prison like?

It was very boring. Lots of time spent reading. I read about 50 books. I wrote about 1,000 letters responding to the people who were writing me. And then I spent the rest of the time eating, playing some trivial game like dominoes or Spades, and talking to the prisoners about how they got there and what their thoughts on the American landscape are.

So it wasn't quite "Oz."

No, in fact, in some of the early interviews [I did] I said my only perspective was watching "Oz," and as I came in there I was completely afraid of what I was going to experience, and it was much more like -- the best way I can describe it is, and I never went to a military boarding school, but it's what I picture a military boarding school would be like during summer vacation or Easter break for the kids that don't go home or something.

Why did you decide to resist the subpoena?

Well, for two reasons. One, I feel that it's important for journalists to assert the rights and privileges that we are afforded under the U.S. Constitution. We already lost some, and this is the only way we'll ever gain them back. And so just on the issue of the rights it was worth resisting.

But then on the other side, it's also crucial that journalists act as the fourth estate and not [work] for the state in pursuing investigations for ... prosecutions. If you're an investigator for the government then you should be getting a paycheck from the government.

Why did you decide to release the video?

That decision had not quite been made, but we had stepped foot down that road in November and inquired whether the U.S. attorney would accept this resolution to the whole thing. We put this forward in November when the en banc wasn't going to be successful, the Circuit second-level appeal. And the U.S. attorney said the only thing he'd ever accept would be full compliance with the demands of the subpoena, which would have involved testifying before the secret grand jury.

And so what happened really wasn't so much that I decided to release the tape as the government decided to go along with our proposal we put forward back then. And the reason that I had come to that decision about releasing the tape is that, while I feel that I should have autonomy to decide what I publish and don't publish, at the end of the day there wasn't anything of a sensitive nature on the unpublished material and as it had become newsworthy in and of itself, once I had exhausted all reasonable appeals there was no reason to deny the public's demand for the material.

Didn't you say at one point that you wouldn't give up the tape?

I believe I said I wouldn't comply with the demands of the subpoena.

And by not comply with the demands of the subpoena, you meant what?

The demand was to testify in front of the grand jury and turn over the tape.

One of the things, though, that a lot of your defenders were talking about was the principle that journalists shouldn't have to give up unpublished material.

They shouldn't.

So how does that play into your decision to release the tape?

Well, there are certain fights that are worth getting into and then when you lose the fight walking away. In a situation where you have material with -- I don't want to say nothing on it, but nothing of an evidentiary value on it -- once you've lost the legal fight, then you're just a martyr for the sake of being a martyr. At that point the fight was for the testimony and not for this video with no real value whatsoever.

Why separate the testimony from the tape? Was there not a principle involved in the tape at that point?

Well, see, the principle is not acting as an investigator. In not putting up a fight to turn over the tape, I'm acting as an investigator, but at the end of the day, once that fight has been lost, there is no material evidence to speak of on the unpublished tape as opposed to the published tape.

What does the content of the tape have to do with the principle?

The content of the tape has nothing to do with the principle. The principle is not turning over broad information to the government to aid in their investigation. It doesn't much matter what that content was, it's not the role of a journalist to be providing evidence whenever the government asks for it.

So why was taking the stand and giving testimony to the grand jury the sticking point for you?

Several reasons. As the grand jury is a secret body, the U.S. attorney was not candid about what questions [were going] to be asked. The only clue we had was an article in the San Francisco Chronicle where Luke Macaulay, who is the spokesperson for the U.S. attorney's office, stated they were seeking my testimony to identify potential witnesses. Not potential suspects, mind you, but potential witnesses [to the arson and beating]. So I had every reason to think that when you take that statement and try to derive what that would mean, I would be put in front of the grand jury, the video would play and every time a new person would enter the frame, I'd be asked whether or not I could identify him or her. Then anyone that I was able to identify would likely go through the same situation, and you would essentially create a witch hunt akin to McCarthyism in the 1950s.

Was there any other journalistic principle involved in refusing to testify?

OK, besides acting as a prosecutor, besides asserting the rights, was there any other journalistic principle?

I'm not questioning your justification, I'm just wondering whether there was an established First Amendment argument or anything like that.

Well, the established First Amendment argument dates back from the Branzburg v. Hayes case ... One of the key issues is that because [a grand jury is] secretive, there's a trust that's going to be lost, because no one's going to be able to verify what was or wasn't said. Secondly, just by acting to aid in the prosecution, it's going to have a deleterious effect on the trust relationship between journalists and their contacts. And then finally, the other argument that I can just recall around the First Amendment issue is that if you have a free press that feels that they're going to be subject either to going against their ethics or going to jail, then the news will stop being news and just become P.R. -- what people want to get out, and not the stuff people fight to keep hidden.

There has been a lot of debate over whether you are a journalist. How would you define yourself?

I define myself as a journalist and a video blogger.

What do you feel makes you a journalist?

The question of who is a journalist is less important than what is journalism. I went out to engage in journalism, to document and cover a demonstration that would have been neglected by the mainstream press, for the purposes of documenting and showing the public what occurred. I feel that that is journalistic activity. And as I do this on a regular basis, I feel that I am a journalist.

How often did you do that sort of thing before the riot?

Well, that sort of thing is a broad thing -- not everything I do is of a political protest, some things I do are writing, some things are of a more fluff, sort of human interest bent. But I'd say that I had a new post on my blog at least once a week, and a new video at least once a month.

Is a blogger a journalist, in your mind? Are you a journalist because you had a blog?

A journalist can be a blogger, a blogger is not necessarily a journalist -- unless they, I mean, and that gets kind of fuzzy because if the sole focus on your blog is your pets, then I guess you are engaging in journalism about your pets, but it's a very, very fine-tuned scope.

So who isn't a journalist in this new media world?

Well, if someone's blog is a work of fiction, then they're more of an artist than a journalist. It's a very fuzzy issue that needs to be discussed; it's an ongoing conversation and one that I don't have all the answers to at this time.

What about the line between activism and journalism that some people were talking about you breaking?

I think a line is crossed when you don't disclose your own personal bias.

You're saying you went out to document this, and that's part of what makes you a journalist. What about a situation like the Rodney King tape, where someone happened upon an event and decided to record it? Does that make them a journalist, in your mind?

That's a different matter. Do they go out and film random events to post on their Web site, or is this just something they happen to do? If they make it a course of action, as far as their daily life, to document the world for the public, then yes, they are a journalist. If they just happen to film this one thing, and they don't even know what they're doing with it at first, then I'd say they'd probably think they weren't a journalist.

And what did you think of the arguments that you're not a journalist?

I think they're missing the point, because we can sit there and hash out who is and isn't a journalist over time. But the real issue is, if you give me the benefit of the doubt and you assume I'm a journalist, then what does this say about the current lack of a federal shield law, and that journalists are protected in 49 states, plus the District of Columbia, in state courts, yet not under federal law.

And what do you think that says?

It says that federal law's not in line with its own components. I can say that in the state of California, in the case of Apple v. ThinkSecret, a California appeals court ruled that bloggers should be considered part of the news media, and that it's not the court's place to decide who is and isn't a journalist. There are several Supreme Court cases that also echo that sentiment, that it's not the government's place to decide who is and isn't a journalist.

Do you think your situation will have any impact on the way people think of what a journalist is and what a journalist isn't over the next few years?

I think it certainly added a lot of fuel to the fire of that debate. The debate has already been going on for the past few years with the rise of blogging. There's no hard and fast way to define who is and who isn't a journalist -- you ask anyone and they're all going to come up with their own sentiments about it. The biggest one that strikes my mind is, I was talking to Rolling Stone, and some other people about Rolling Stone and it's like -- rock journalism. Not everyone's going to consider someone who's doing a piece about Metallica to be a journalist, but they're disseminating news about a specific area of interest and they should be considered journalists for every reason.

Do you have any regrets?

Little tiny ones like, "I should have put this on the site when this happened." My biggest regret is not being better organized in the lead-up to my imprisonment.

What do you mean by that?

Building a support network -- making sure that I have someone in place to upload the blogs, having a more in-depth comprehensive site surrounding the actual case already established, making sure that my bills were set to pay. All the sort of boring stuff that dictates our everyday lives but can't be handled from behind the prison walls.

Would you do this again?

Absolutely.

Shares