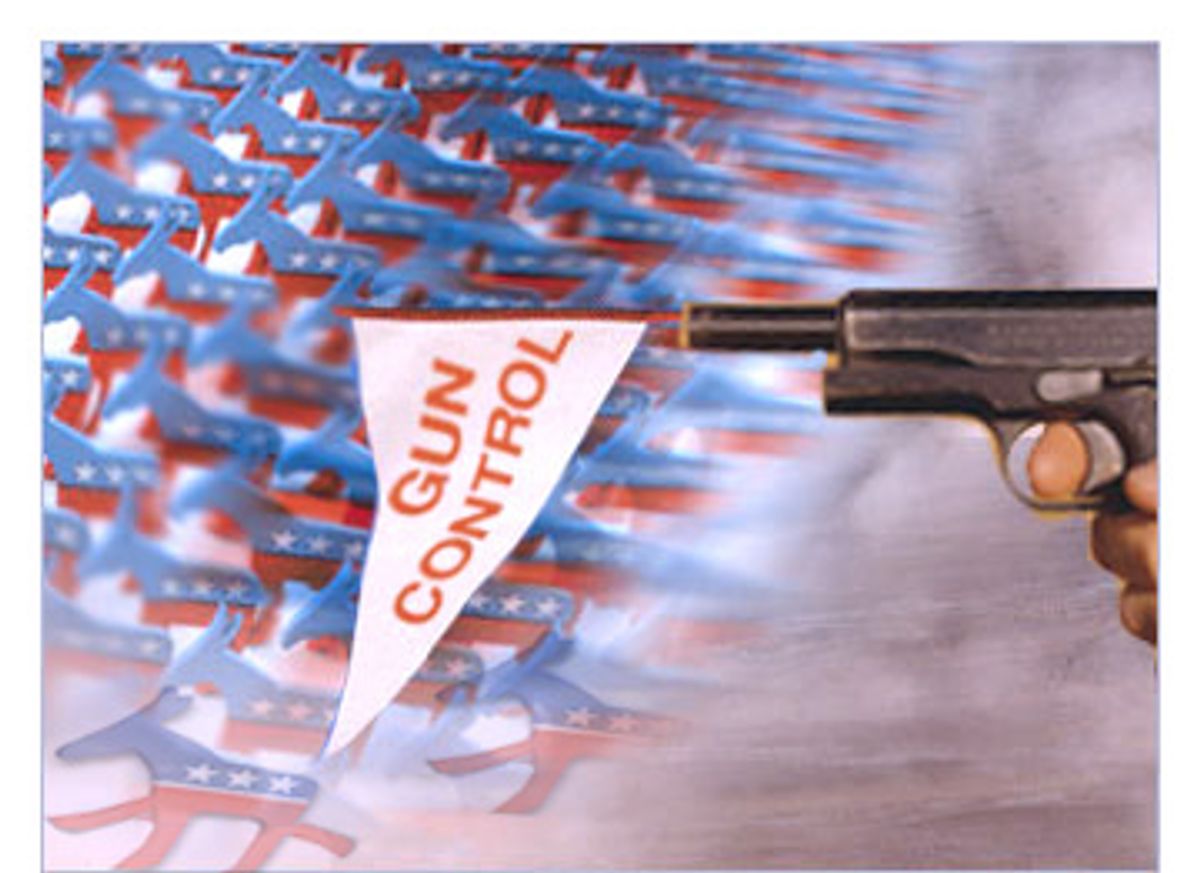

Monday's mass shooting on the campus of Virginia Tech will undoubtedly lead, as so many tragedies do, to a search for answers, for those measures that will ensure that something like the massacre in Blacksburg never happens again. And that search will almost inevitably lead, as it has in the past, to a discussion of gun control.

During the Bush administration, however, gun control has been all but dead as a political issue, and though George W. Bush is one of the most pro-gun presidents in history, much of the responsibility lies with Democrats. Once a popular talking point for Democratic officials and candidates, gun control has been shoved to the background over the past six years, as the party -- trying not to alienate gun-owning voters in swing states -- has cooled its rhetoric on the issue and tamped down its action. Gun control advocates haven't won a major victory since Bill Clinton was president, and since then the main anti-gun legislation of the Clinton era has either died or been stripped of its teeth.

"We've gone backwards in a lot of areas," says Paul Helmke, president of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence. "In effect, the only real gun law we've got on the books now is the Brady background checks."

Robert J. Spitzer, a distinguished service professor of political science at the State University of New York at Cortland, who wrote the book "The Politics of Gun Control," agrees. "It's an issue that's largely off the table," Spitzer explains. "You've got, basically, the Democrats running away from the issue and deciding that this is not where they want to hang their hats, and Republicans who are . . . extremely sympathetic to the policy goals of the [National Rifle Association]."

Democrats have been turning away from gun control ever since Al Gore's run for the presidency. The then-vice president and his advisors had tried to out-gun-control liberal challenger Bill Bradley during the Democratic primaries. Campaigning against George W. Bush in the general election, Gore decided to quiet his criticism of the NRA and mute his support for gun control to build support in battleground states like Ohio, Pennsylvania and Michigan where support for gun rights runs high. In the wake of Gore's loss, many Democrats blamed the defeat on previous pro-gun control positions Gore had taken, and pulled the party further back from where it had been on the issue.

Today, a substantial portion of the party's new standard-bearers are pro-gun, or at least anti-gun control. Howard Dean, the former Vermont governor who now heads the Democratic National Committee and is the favorite of the new party power base emerging from the Internet, has long been an opponent of gun control. So has Sen. Jim Webb, D-Va., the man whose squeaker victory in November gave Democrats control of the Senate and who was selected to give the party's response to President Bush's State of the Union address this year. Last month, one of Webb's aides was arrested on his way in to a Senate building with one of Webb's guns in his possession. Webb responded with a spirited defense of his right and need to bear arms. Even Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev., the new Senate majority leader, is pro-gun.

Recently, the party actually used a Republican's apparently lukewarm devotion to guns against him. A press release put out by the DNC hit former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, currently a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, on his record of support for gun control and conflicting statements on his own use of guns. In the release, DNC spokesman Damien LaVera ridiculed Romney, saying, "Either Mitt Romney's brand new NRA lifetime membership card wasn't activated in time to get him into the convention or Romney was afraid he wouldn't be able to smooth talk his way out of his record on gun issues."

Along with the Democratic Party's turn away from a strong public stance on gun control has come a reversal of some of the victories that gun-control advocates won during the administration of former President Bill Clinton. Primary among those victories was the federal assault weapons ban, which was passed in 1994, but included a "sunset provision" that mandated its expiration 10 years later. In 2004, Democrats in the Senate did manage to approve, by a vote of 52-47, an extension of the ban as a rider attached by Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., to another bill. But that was relatively uncontroversial; that year, the University of Pennsylvania's National Annenberg Election Survey found that 71 percent of people in households without guns, and 64 percent of people in households with them, supported continuing the ban. Even 46 percent of people living with an NRA member favored the ban. President Bush was also a supporter, if a lukewarm one.

Yet despite that level of public approval, Democrats couldn't get a continuation of the ban to stick. Part of the problem was that the bill to which the extension of the ban and all the other riders were attached, S. 1805, banned many types of lawsuits against gun manufacturers and sellers. It was a pet project of the NRA, and all the riders may have been intended as "poison pills." Opponents of the proposed law, who didn't have enough votes to kill it outright, weighted it down with a series of gun-control amendments that would be unacceptable to the NRA. An amendment that would have closed the loophole that applies to gun shows, and forced sellers there to conduct background checks on buyers, was attached by a vote of 53-46, as was another amendment to require the provision of child safety locks whenever ownership of a handgun was transferred. (Another amendment, however, that would have expanded the ban on armor-piercing ammunition, went down to defeat, 34-63. Thirteen Democrats, including then Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle and current Majority Leader Reid, crossed the aisle to vote against that amendment.)

Ultimately, because of the gun-control provisions that had been tacked on to the lawsuit immunity bill, the NRA turned against a bill it had once backed. The group asked its supporters in the Senate to kill the measure. They did, 90-8.

But the lawsuit immunity bill returned, and, after Republicans picked up Senate seats in the 2004 elections, it was eventually passed by Congress. The assault weapons ban, on the other hand, was not, nor were any of the other gun-control amendments that had once been added to the immunity bill. In September of 2004, the original assault weapons ban passed in 1994 expired and assault weapons became legal again. Since then, Democratic attempts to bring the ban back have faltered.

The expiration of the ban may have had some consequences in Blacksburg. ABC News has speculated that the shooter probably used a high-capacity ammunition clip of a type that was prohibited under the ban but became widely available when the ban expired. The other major piece of anti-gun legislation passed in the Clinton era, the Brady Bill, has been weakened as well, because of rules put in place by former Attorney General John Ashcroft when he took office in 2001.

The desire to court voters in swing states with a large percentage of gun owners is the primary reason that Democrats have recently tended to view the issue of gun control as poisonous. There were other reasons as well, however. First, there were fears that support for gun control could split a key Democratic constituency: union members. A survey done by Americans for Gun Safety has shown that 54 percent of union households own a gun. Moreover, gun control is an issue with what Spitzer describes as "hassle" and "intensity" factors that don't favor advocates. Supporters of gun rights are passionate in a way that supporters of gun control are not -- gun-rights backers are single-issue voters and activists, while on the other side, Spitzer says, "the typical gun control supporter is somebody for whom the issue is not a No. 1 concern, it's No. 6 or No. 8."

Doug Hattaway, who was national spokesman for Gore's 2000 campaign and is now the president of Hattaway Communications, concurs. Hattaway notes that organizations like the Brady Campaign cite the high public support for gun control measures, but says that support doesn't translate into electoral victories for Democrats.

"There's a difference between agreeing on an issue and having it motivate your vote," Hattaway says. "Yes, people agree, but there's not a potent pro-gun control constituency in national elections."

There is, on the other hand, some potential downside that can come with being a supporter of gun control, the "hassle factor" to which Spitzer refers.

"The NRA and its allies are pretty good at hassling gun-control people," Spitzer says. "For somebody like [Sen.] Chuck Schumer [D-N.Y.], that won't matter much, but there are a lot of Democrats for whom it will matter."

Much of the Democrats' shift on the issue can be traced back to the elections of 2000. Matt Bennett, who is vice president for public affairs at the centrist think tank Third Way, which grew out of Americans for Gun Safety -- AGS is now a project of Third Way -- says that after Gore's defeat, "A lot of people -- [former DNC Chairman Terry] McAuliffe, Daschle, [former House Minority Leader Dick] Gephardt -- were going around saying that guns had been the key ... There was a lot of talk about how Democrats should avoid the issue entirely."

As Franklin Foer reported in the New Republic, "The hand-wringing began just as the Supreme Court awarded Florida's electoral votes to George W. Bush." Early in December, by Foer's telling, then-House Minority Leader Dick Gephardt, D-Mo., summoned House Democrats to his Capitol office, 20 at a time, and gave a sales presentation. Pollster Mark Gersh pointed to charts and told the Democrats they'd lost because culture war issues, especially gun control, had distracted voters. Many apparently went away convinced.

By the middle of 2001, ditching gun control had become conventional wisdom among centrist Democrats. Sen. Zell Miller, D-Ga., said Al Gore had talked about it too much. Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, Gore's running mate, thought gun control had cost the Democratic ticket "a number of voters who on almost every other issue realized they'd be better off with Al Gore." Terry McAuliffe, head of the Democratic National Committee, in particular wanted his party to drop the issue. In a June 2001 article discussing McAuliffe's strategy, Roger Simon cited a strong correlation between gun ownership and voting for Bush, as demonstrated by exit poll stats. "Guns made a big difference in 2000," argued Simon, "especially in some key states that Al Gore lost, like Tennessee and Arkansas." What Simon did not establish was how many of these gun owners considered gun control a paramount issue, or whether any of them would've chosen Gore over Bush if the vice president had moved further or earlier to the right.

Once this new consensus had emerged, says Matt Bennett, "That's when Americans for Gun Safety came on the scene." AGS advocated a new approach to Democrats' language on gun issues, and the Democratic Leadership Council, a centrist faction within the party, allied itself with the group. In July 2001, AGS president Jonathan Cowan and policy director Jim Kessler took to the pages of Blueprint, the DLC's house magazine, to explain their thinking in an article titled "Changing the Gun Debate."

"The solution isn't to clam up on guns," Cowan and Kessler wrote, "but rather to change the terms of the gun debate ... It's time for Democrats -- and progressive Republicans -- to embrace a 'third way' gun policy that treats gun ownership as neither an absolute right nor an absolute wrong and that calls for a balance between gun rights and gun responsibilities. To win elections, Democrats need to reason with gun owners rather than insult them."

There is, perhaps, no better example of the way this message has been embraced by the Democratic Party than the 2004 presidential campaign of Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass. As Bennett notes, the Kerry campaign wanted voters to see photos of the senator, an accomplished marksman, in action with a hunting rifle. And when Kerry came back to the Senate in March of 2004 to vote on the assault weapons ban, he was on message, using the standard AGS formulation that combines language about rights with language about responsibilities.

Indeed, says Kessler, aides to all the major candidates of the 2004 Democratic presidential primary series met with AGS; he names Dean, Gephardt, Kerry, retired Gen. Wesley Clark, Lieberman and former Sen. John Edwards as candidates whose staffs came to AGS "asking what to do and how to frame things."

Hattaway, who was also a consultant for AGS, credits the organization with the change in the Democratic Party's message on the issue.

"Tremendous progress has been made in taking the issue off the table and reducing the potency of the NRA," Hattaway says. "I'd say Americans for Gun Safety were the force in improving the Democrats' position."

On the other side, Helmke, of the Brady Campaign, is frustrated with the Democrats' shift, though he notes that they aren't the only ones to play with the language of the debate -- the Brady Campaign used to be called Handgun Control Inc. Still, he thinks the contention that gun control is a losing issue is untrue.

"That's the myth that a lot of the politicians and the consultants bought into, that if you mentioned the words 'gun control' ... you were going to catch it from the other side," Helmke says. "I think what's happening is that most of the consultant types are saying stay away from this issue, it's a loser ... [But] I have tried to convince Democrats that they can address gun control if they do it the right way."

Shares