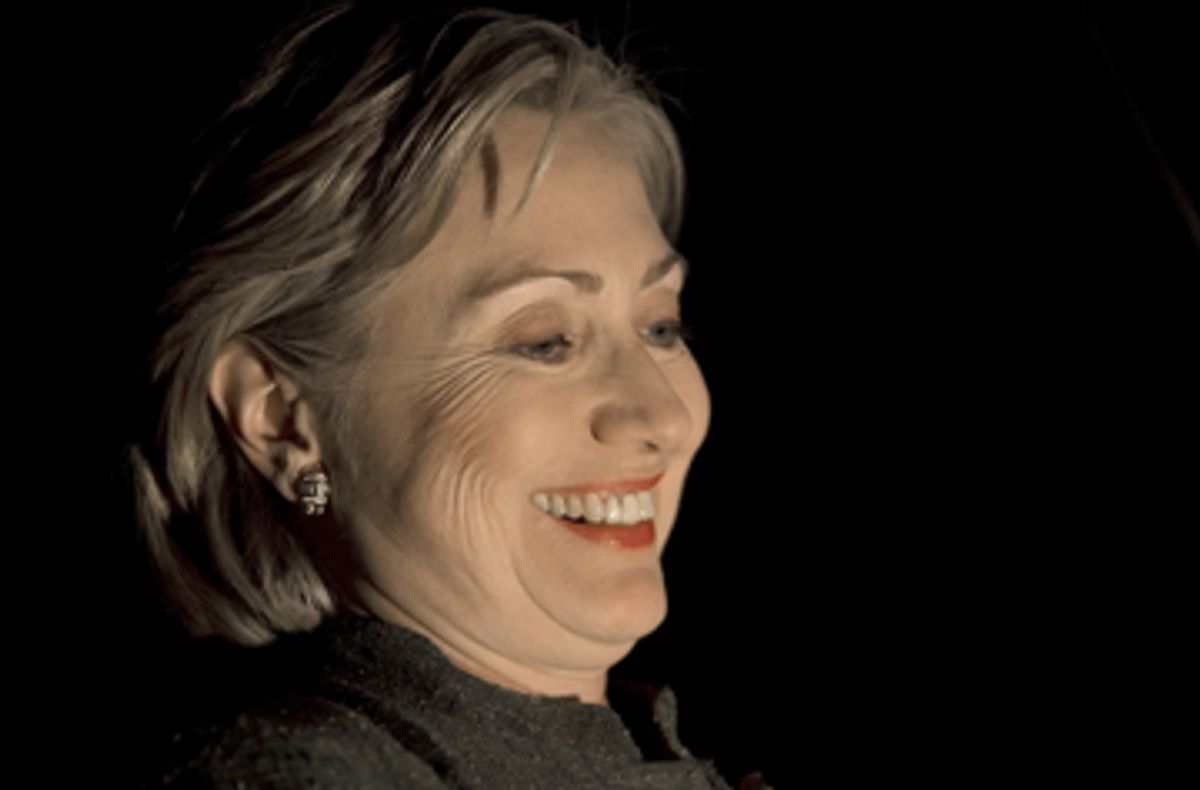

Hillary Clinton was interviewed over the telephone by Salon last Thursday afternoon before she flew to New Hampshire.

The first time I interviewed you was in the governor's mansion in Little Rock in 1992. So I was tempted to ask: Anything happen in your life since then?

Oh, I don't know. What's new with you?

You were quoted the other day when asked about Barack Obama's fundraising numbers and you said that if he out-raised you in the second quarter, "It would mean nothing to my campaign." What did you mean by that? Are you saying that we in the press place too much importance on fundraising numbers?

Well, I'm afraid you might [be over-emphasizing fundraising numbers]. Because the real challenge is whether you have a strategy you're pursuing and the resources to implement your strategy. When I ran in 2000, I was outraised and outspent by nearly 2-to-1 by both of my opponents. It never bothered me for a moment because my concern was making sure that I had the resources -- which I did -- to run my campaign as I expected it to run.

And that's how I feel about this. We've done very well. We will continue to do very well. But I keep focused on what I'm doing. I have no control over what anybody else does. And it has served me well -- and I think it will serve me well in this campaign. And it will serve me well when I'm president.

Let me ask something that comes up every time I write about you. I sometimes refer to you on, say, the fifth reference as "Hillary" instead of "Clinton." I always get three or four letters saying that I am demeaning women by referring to you by your first name. But your campaign materials refer to you as "Hillary" and the word "Clinton" might also apply to another well-known public person. Do you have any feelings about this? Am I offending you every time I type "Hillary, Obama and Edwards"? Or do you have an open mind as long as I spell Hillary correctly?

I probably have more of an open mind. But I understand the point people are taking because if you also refer to Rudy and Mitt and John then that would be even-handed. I get the same indignation from a lot of women who read you and others and say, "They never call the other candidates by their first name."

And I think that in print -- as opposed to building a campaign that really does use my first name because it is so identified with who I am -- that's the concern that people have.

For Democratic voters, one of the ways of sorting out the field is electability. Do you think electability should include how would this candidate do in a three-way race in which Mike Bloomberg, running as an independent, is part of it?

Well, I'm not going to answer hypotheticals because again I want to keep focused on running my campaign to the best of my ability. And I have no influence or control over what anybody else does to get in, or get out, or run on a third party. But I feel very confident that I can put together a winning campaign no matter who my opponents are.

Six months into a Hillary Clinton administration, about how many U.S. military personnel do you envision being in Iraq to handle what you've referred to in the past as "vital national security interests" -- from helping the Kurds to preventing Iran from crossing the border?

I cannot give you a figure because I will not become president until January 2009 and there is no way to predict what will occur between now and then. I have said repeatedly that I am committed to taking our combat troops out of the midst of this sectarian civil war. And there may well be vital national security interests that require a continuing presence, although I do not support permanent bases or a permanent occupation. When I'm elected -- and between the time that I am elected and the time I become president -- I will focus to a great extent (and nearly to the exclusion of a lot of other important matters) on being ready to make those decisions once I become president.

But it is just impossible to make any kind of credible predictions at this point. I am still hoping that the president will decide to follow the Iraq Study Group's recommendations and begin to alter the makeup and mission of our force before he leaves office. I think it is his responsibility to do that. So that's my principal emphasis during this time -- to try to persuade or require him to take the steps that I would have to do initially if he has not.

Following up on that: Do you think that the Democratic primary voters -- the people you talk to every day who are so palpably eager to end this war -- need to understand that there are certain national security roles that the U.S. would have to continue to play in Iraq, even after we take out the combat troops?

I have a lot of confidence in the electorate both in the primary and the general election. I think voters are hungry for people who will explain to them the complexities of the problems we face, the difficult challenges we will inherit.

So for me, in my discussions, of course, we would all like to turn the clock back. We would certainly like to begin withdrawing troops as soon as we can. It is complicated and dangerous to withdraw troops. That's one of the reasons why a few weeks ago I wrote to Secretary [of Defense] Gates asking that he ensure that there is a serious planning process under way right now -- not just the usual contingency plans on the shelf, but operational planning -- to begin to be prepared to withdraw troops.

Our troops and their equipment will be extremely vulnerable. There are only two ways to get them out. One [is] through the north through Turkey -- and you recall that Turkey did not allow us to move troops through their country [at the start of the war]. So therefore, we will have to go south. And long convoys are vulnerable; they are the principal battlefield where our soldiers are wounded and killed by the explosive devices used against them.

So I talk a lot about the complexity of the decisions that we have to be aware of in our country -- that I will have to face as president. And that's why I am trying to push this president to begin to prepare us. Because if we are to start tomorrow to begin ordering our troops both out of combat, which we can do, and have them move back to the bases we have established there [it takes preparation]. But if we are going to begin to move them and their equipment out of Iraq, that is something that I will be very concerned about because of the dangers that will accompany that kind of withdrawal.

I've talked to Democratic voters who say that they really want to support you but they're really concerned that America would be becoming some sort of oligarchy if just two families divided the White House for 24 or even 28 years. What would you say to a Democratic voter like that?

Well, I'm running on my qualifications and experience. I am proud to have been part of the Clinton administration where I think we got a lot of things right during those eight years. We are going to propose plans of action that will be future-oriented. But there are some lessons, both what to do and what not to do, that I certainly learned during the Clinton administration that I will put to work as president. And I am asking the voters to judge me along with my opponents as to what I bring to this campaign.

In a democracy, the right of any voter [is] to choose any reason to vote for or against anyone running. And I hope I will be able to make the case over time to a majority of voters that my experience gives me an edge -- that I understand the challenges we're going to face and that I will be able to marshal the resources in order to begin addressing them from Day One. That to me is essential. Every president faces a difficult period in office. It comes with the territory and it's the hardest job in the world. It always has been. But it is made more so by what we will inherit. So we really don't have any time to waste. You have to be incredibly well prepared from Day One to deal with the range of domestic and international challenges and threats that we face.

So I think it's an advantage for my candidacy that I have this experience and it certainly is one of the qualifications that I am presenting to voters.

Let's talk about a couple of specifics. As we both remember, too much time was spent on selecting a Cabinet in 1993 and too little time was spent on selecting a White House staff. One of the results of that was all of the internal turmoil that, I suspect, you remember from 1993. As president, what lessons would you draw from that experience?

Oh, I think I learned an enormous amount. You spend so much time and energy on the campaign and then you wake up the morning after the election and you're going to be the president of the United States in a short period of time and there is so much work to do.

You really do have to, as soon as you get the nomination, begin to think about that. It is not presumptuous, it is prudent to begin thinking clearly about what you will have to face and who you need to recruit and have around you in order to do the people's business from Day One.

We also didn't have a lot of firsthand experience in Washington [in 1993]. I think I have a great advantage having had both the White House experience as well as the prior experience in a state, which is very important for a president to know how that works.

But now especially for my term in the Senate -- I learned a lot of things in the last six years that I wish I had known 15 years ago. But I think that the cumulative experience has persuaded me [of the need for] really understanding the team that you will build. And the strengths and weaknesses that you have to balance against, because every one of us brings strengths and weaknesses. And a good president -- and this is something I think I'm especially sensitive to -- will want a diversity of opinion, will want to be surrounded by people who have experience and expertise that balances mine. I'm afraid that President Bush has had too small a circle of advisors and decision makers, which I think is both to his detriment and the detriment of our country.

So I am very anxious to learn the lessons from previous presidents -- including Bill. I will make my own mistakes, I think that goes with the territory. I have no doubt about that. But I am going to try very hard to think through carefully how to be as well prepared, to have the agenda ready, to have the relationships with the Congress, to have the staff -- the Cabinet and advisors -- really ready to provide a balance that will give us the strongest possible team going forward.

You just mentioned lessons from the Senate that you wished you had known back in the White House days. Could you be specific about a couple of them?

Certainly the way the Senate, and the Congress more generally, works is something that you can look at from the outside, but you can't really fully appreciate it until you're in it. And we got a lot of advice -- I got a lot of advice, let me put it in personal terms -- back in '93 about healthcare. And some of that advice didn't work out so well.

And I understand so much better [now] than I ever could have then. You could have handed me a book or given me a lecture. But I now feel it and understand it in my core about how to work with the Congress. The lead that the Congress has to take in order for it to feel and be a full partner that a president needs. The direction [that] the president has to provide. But [that comes with] the understanding that the Congress has to work its will. You can't expect it to be done automatically or just exactly the way that you want it. There's room for improving it, for making compromises.

That sounds simplistic. But president after president has run into some real hurdles trying to impose his will on Congress when I think what you want is to try to create a common will that will be built on relationships. You know I have very good relationships in the Congress, and certainly on a bipartisan basis, that I have developed. And I think I can find partners across the aisle on a number of issues that will be important to the country. So it's what comes with experience. I have lived it, I have seen it firsthand. And I will carry it with me to the White House.

What have you learned about combating the right-wing attack machine -- the vast right-wing conspiracy, if you will -- that you know now that you wish you knew in 1993 and 1994?

[Laughter].

The laughter will be noted.

Number one, you have to stay focused on what you're trying to achieve. And if you're attacked, then obviously you respond. But you don't go seeking it, and you certainly don't go trying to make that your modus operandi. What you're looking for is a positive message and a positive agenda that you can make your own. And to try to bring as many people to the table as is possible. And then draw lines wherever necessary. That is essential -- that you draw those lines on things that will be important. You can work with people across the aisle, you can work with people who have a different ideology. But there are some things you just have to stand your ground on. Understanding that and being able to navigate through that is a challenge, but you have to be able to do it.

Thank you. I look forward to seeing you across a crowded room Friday in New Hampshire.

Shares